Conflict in the South China Sea by J.R. Dunn

It’s a cliché that generals are always preparing to fight the last war. But that’s also true of writers, both fiction and nonfiction. While there is no lack of speculation about future conflicts, the most likely of these has largely been overlooked. It’s not going to happen in the MidEast, it’s not going to happen in central Europe, and it’s not going to happen in Korea.

“Blue China”

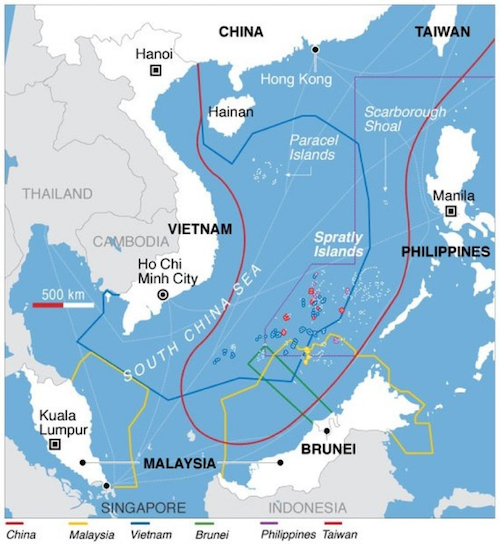

The site of the next major war is the South China Sea, a nearly enclosed section of the Pacific 1.35 million miles in extent, bordered on the north by Southern China and Taiwan, on the east by the Philippines, on the south by Malaysia, Indonesia, and Brunei, and on the west by Vietnam.

Within that extent lies two major island chains (if the term can used for such a collection of acre-wide pea-patches) the Spratlys, a not far from the Philippine island of Palawan, and the Paracels a few hundred miles southwest of Hainan Island. Other islands include Scarborough Shoal (known as Huangyan Island to the Chinese), the Pratas Islands, and the Macclesfield Bank, along with hundreds of shoals, reefs, and sand banks, many of them nameless, some of them only intermittently visible above the surface.

Map courtesy Flikr. Source: D.Rosenberg/MiddleburyCollege/HarvardAsiaQuarterly/PhilGov’t.

China has laid claim to the entire sea as a region it has christened “Blue China,” as integral to the Chinese nation as the Forbidden City or the Great Wall. Blue China is the area enclosed by the “nine-dash-line” an imaginary and extremely vague borderline that follows no physical entity known to geographers. The line forms a feature known as the “cow’s tongue.” (It’s remarkable how much cow imagery infuses Chinese rhetoric. One of the worst accusations that could hurled during the Great Cultural Revolution was “cow demon.”)

The Chinese claim is absurd on the face of it. The “cow’s tongue” stretches 1800 miles from the Chinese mainland to a point only a stone’s throw from Malaysia, ending at the James Shoal, one of those features that spends most of its time under water. The Chinese claim conflicts with those of all bordering countries (all of which are dismissed by the Chinese as simply elements of the “First Island Chain”), including the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, Brunei, and Malaysia. Most of these claims are legitimized by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which provides for a 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone for each maritime state. Many of the Spratlys lie within the Philippines’ 200-mile limit, but are over 500 miles from any Chinese territory, while the Paracels are split between the maritime limits of China and Vietnam.

The South China Sea is an extremely valuable piece of territory. It contains nearly one-tenth of terrestrial fishery reserves, which play a large role in feeding the one-and-half-billion people lining its shores. It is estimated to contain 11 billion barrels of oil and 190 trillion cubic feet of natural gas (some of it in the form of “flammable ice.”). It’s also a crucial waterway, with over $5 trillion in trade transiting its waters annually, including up to fifty percent of the world’s oil, on its way to China, Japan, and the west coast of the U.S.

Clearly, the country that controls the South China Sea has a stranglehold on East Asia and points beyond—which appears to be exactly what the Chinese have in mind.

China Presses its Claim

The nine-dash-line is not a communist daydream but was something inherited from the previous regime. In 1947 the Nationalist government proclaimed ownership of the South China Sea by means of a map showing the nine-dash-line encompassing the area. The claim was based on assertions that China had controlled the entire expanse as long before as the Tang dynasty in the 9th century. In fact, there was no sign of any Chinese maritime activity before the 15th century—and that must have ended when the Chinese fleet was scrapped late in the century.

The communists held off on pressing their claim until they had amassed the military and economic clout to make it stick. The first confrontation occurred on January 19, 1974, when a South Vietnamese Navy flotilla attempted to dislodge a Chinese People’s Liberation Army unit on Duncan Island in the Paracels. The Vietnamese troops were repulsed and the supporting ships, three frigates and a corvette, were outmaneuvered by the four Chinese minesweepers present, with the corvette sunk and the three frigates driven off. Fifty-three Vietnamese were killed and sixteen wounded, with another forty-eight taken prisoner.

That skirmish initiated a series of confrontations between China and the region’s other states that continued for forty years. In 1988 Vietnam, united under the communist Hanoi government, made another stab at defying the Chinese, this time in the Spratlys. Detecting Chinese ships in the area, Vietnam decided to forestall Beijing by immediately occupying the islands. Two armed transports were sent to the Union Banks area of the Spratlys, where they planted the PRV flag on Johnson South Reef, one of those islands that only occasionally appears above water. On March 14, the reef was approached by three Chinese frigates. Vietnamese troops landed to defend the flag, and were soon confronted by armed landing craft filled with Chinese marines. Film footage shows Chinese troops, backed by the frigates, cutting down the Vietnamese troops standing in waist-deep water with machine-gun fire. The frigates then turned on the Vietnamese vessels, sinking them both. Sixty-four Vietnamese were killed in the battle. Video reference here:

Hostilities over the islands have continued at a low boil ever since. The Chinese have repeatedly attacked Vietnamese fishing boats, on several occasions sinking them by means of ramming. In June 2011, a Chinese “fishing boat” harassed a Vietnamese oil exploration vessel, cutting its cables by ramming. Three years later, in May 2014, Chinese vessels turned water cannons on a Vietnamese flotilla subjecting a Chinese drilling rig near the Paracels to turnabout treatment. The Chinese were forced to pull the rig back, an event celebrated as a major victory by the Vietnamese. Video reference here:

Philippine fishing and patrol boats were subject to same type of treatment. One epic encounter involved Second Thomas Shoal in the Spratlys, where in 1999 the Philippines grounded a surplus landing craft to mark its claim. The vessel, manned by a small unit of marines, has served as an outpost ever since—surely one of the worst military billets in the modern world. The Chinese have made numerous attempts to lay siege or otherwise shut down the outpost.

In April 2012, the Philippine Navy intercepted eight Chinese fishing boats at Scarborough Shoal. This led to a standoff with Chinese forces, with the Filipinos forced to withdraw after two months. As with previous confrontations, the Chinese proceeded to occupy the shoal.

Filipino president Benigno Aquino responded by appealing to the UN under the provisions of the UNCLOS treaty. In July 2016, the UN tribunal found in favor the Philippines, dismissing Chinese claims in the region. The Chinese, needless to say, ignored the decision, asserting that it was “unfounded.” Aquino’s successor, the erratic Rodrigo Duterte, has chosen to overlook the UN decision in favor of closer ties with China.

In addition to the local powers, China has also harassed third parties in the South China Sea, including the U.S. In recent years, several American ships and aircraft have suffered near-collisions caused by Chinese interference. In December 2016, during the waning weeks of the Obama administration, a U.S. Navy drone was seized by the Chinese only fifty miles from the Philippines. This was generally interpreted as a message for the incoming Trump administration.

Island Building

China made its boldest move involving the South China Sea beginning in 2013.

Let it never be said that the Chinese are not innovative. China is clearly unafraid of novelties, as witnessed by its unique (and yet unproven) mixture of centralized authoritarianism and freebooting capitalism. The response to foreign challenges to its maritime claims was also innovative. Lacking any firm ground to make a stand, the Chinese went ahead and created it.

By 2013 it was apparent that the Obama administration’s “pivot toward Asia” was mere rhetoric, and that the U.S. had instead slipped into another one of its isolationist doldrums. The Chinese were quick to take advantage. In a massive dredging operation involving dozens of gigantic ocean-going dredges, China built up a series of shoals and sandbars in the Spratlys and Paracels into full-fledged islands capable of supporting substantial military establishments.

Seven islands in the Spratlys and Paracels were restructured—Fiery Cross Reef, Subi Reef, the aptly named Mischief Reef in the Spratlys, and Triton, North, Tree, and Woody islands in the Paracels. Most of the actual island creation occurred in the Spratlys. It appears that the Chinese are treating the more easterly islands as a strategic glacis to act as a block against an advance into the area. The total new acreage amounts to seventy-two acres, or 290,000 square meters.

Fiery Cross Reef, originally a coral outcropping a little more than a meter in height, was the site that received the largest refurbishing, with twenty-seven acres (110,000 square meters) of new land. New features included a 10,000-foot-long runway capable of handling any aircraft in the Chinese inventory, and a harbor capable of handling troopships. An enormous communications array was constructed, along with a high-frequency radar site at the northern end of the island. The island’s new barracks can accommodate up to a full battalion of troops.

Woody Island, Subi, and Mischief reefs also feature long runways. Smaller islands have helipads, radar stations, and SAM or ground-launched cruise missile installations. Mischief, Subi, and Fiery Cross Reefs are also home to elaborate buried storage tunnel networks.

Dredging operations at Subi Reef. Image courtesy U.S. Navy.

Woody Island in the Paracels acts as China’s headquarters for the South China Sea, featuring a large array of advanced communications equipment. China’s mainstay operational fighter, the J-11B, has been spotted using the air base, along with Y-8 heavy transports. Woody Island also features the region’s premier geopolitical oddity, the metropolis of Sansha, which in 2012 was declared a “prefectural level city,” a designation usually reserved for cities of upwards of a million people. Sansha’s population is all of 1,500. Evidently plans to turn it into a tourist resort and cruise ship destination are well in hand.

Basically, the Chinese set about creating a network of island fortresses to defend their claims over the South China Sea. In response, the surrounding nations have increased their military budgets by a third, with arms purchases skyrocketing. Malaysia increased its weapons imports by over 700 percent, while Indonesia and Singapore made smaller but still substantial increases. Vietnam has purchased six Kilo-class submarines from the Russians, something that would concentrate the minds of anyone but the Chinese, along with $1 billion worth of Russian fighters.

The U.S. response was to carry out more freedom of navigation cruises through the area, to underline both the UNCLOS rules and the American doctrine of freedom of passage on the high seas. In this, it was joined by other Western states, the UK and Japan in particular.

One of the most recent of these missions, in March of this year, involved an entire carrier battle group centered on the USS Carl Vinson (CVN-70), a Nimitz-class supercarrier. Accompanied by several Aegis guided-missile-equipped escorts, the Vinson transited the South China Sea without incident, followed by a visit to the People’s Republic of Vietnam (March 5-9), where the Vinson strike group docked at the old American base at Da Nang and the ship played host to a number of Vietnamese officials. It marked a high point in the two-decade rapprochement between the old enemies.

Immediately afterward, the Vinson cruised northward, again entering the disputed waters, to rendezvous with a task force of Japan’s Maritime Self-Defense Force (MSDF) centered around the Ise, a helicopter carrier also capable of fielding the F-35B Lightning II. The combined force carried out joint exercises for several days within spitting distance of the new Chinese installations.

A more pointed gesture regarding Chinese pretensions in the area can scarcely be imagined. Clearly, the U.S. is beginning to pull together a regional alliance against Chinese aggression. Although Chinese government officials and state media fulminated against the U.S., promising everything up to the apocalypse itself, an actual response failed to occur.

If considered solely as an effort to extend national power, the Chinese program in the South China Sea must be viewed as a success. Over a period of decades, China, once the Sick Man of Asia, has carried out a series of carefully calibrated moves—only a small fraction of which involved violence—to gain effective control over its near overseas region, the South China Sea and the nations bordering it. This has been accomplished without unduly straining relations with most foreign countries or adversely affecting China’s international standing. The end result could be viewed as something resembling the control the U.S. exercises over the Caribbean and its contiguous states.

But that’s not all there is to it, because China has a deeper agenda. Over the long term, China wants two things: to eject the U.S. from the Western Pacific and to exercise total hegemony over the entire region.

“Hegemony” is a concept not often mentioned in the West that plays a large role in Chinese political thinking, both domestically and in foreign relations. It’s a product of their imperial history, reinforced by decades of Maoist communism. To the Chinese, there is no comity of nations, no partnership between equals—there is the dominant power and those that are dominated, a strict hierarchy in which only a single major power can exist. From the Chinese viewpoint, the United States is the dominating power in the Western Pacific—their neighborhood. The fact that the U.S. has acted as a peacekeeping, nonbelligerent force (excepting gross errors such as the Vietnam War) protecting the status quo and the rights of local nations, means nothing to the Chinese, even though China itself has prospered under the U.S. umbrella. The newly militarized South China Sea is, from the Chinese standpoint, the first step in ejecting a weakened U.S. from the region and ensuring Chinese hegemony over East Asia.

From this point of view, the Chinese efforts don’t look quite so impressive. In fact, they look like a sure recipe for failure.

A major flaw is that China is challenging the U.S. at one of its strongest points—the U.S. Navy, which, along with the Marine Corps, comprises one of the most successful military forces of the modern epoch. Furthermore, the Chinese are playing into one of the Navy/USMC’s chief strengths: opposed assaults against enemy island-based installations. U.S. naval forces have carried out dozens of these, once considered to be one of the most difficult of military operations, during WW II, Korea, and the Grenada invasion, and have never once been defeated. Even in its current condition, weakened by decades of neglect and politically correct personnel and promotional policies, the U.S. Navy remains the most potent maritime force on the planet, one that an opponent challenges at his peril.

In addition, China is also confronting one of the great secondary maritime nations, one that gave the U.S. Navy itself a run for its money within living memory—that being Japan. While post-World War II Japan has downplayed military power as a means of carrying out national policy, that can change at any time, and in fact, it is undergoing an evolution at this very moment.

Because the South China Sea is not the only Pacific crisis involving China. There is also the long-simmering dispute in the East China Sea, south of the Korean peninsula and encompassing the area between the Ryukyus and the northern Chinese coast. China also claims this 81,000-square-mile region, along with all the islands within it, including the Senkaku island chain (called the Diaoyu in Beijing), dismissing the fact that these islands are already claimed and occupied by Japan. For the past decade, China has waged an unrelenting campaign of harassment against Japan. Constant violations of Japanese airspace by military aircraft—up to 700 a year—accompanied by regular naval incursions, have become a way of life in the area. In 2013, the Chinese declared an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) over the East China Sea, which was ignored by both Japan and the U.S. Japan responded by buying up three of the five major islands, which had been privately owned, and proceeded to arm them, along with the Ryukyus, with advanced mobile antishipping and antiaircraft missiles. It seems that Chinese policy has succeeded only in awakening one of its great national nightmares—a militarily powerful Japan. (In a development not unrelated, the USAF in October 2017 sent the 34th Fighter Squadron, equipped with F-35A stealth fighters, to Kadena Air Base at Okinawa for exercises. Some of these occurred over the disputed waters, and also involved pilots of the Japanese Air Self-Defense Force [JASDF].)

China’s Strategy

For the moment, Chinese strategy in the South China Sea seems to be aimed at anti-access/area denial (A2AD). With its island fortresses, integrated radar and communications systems, and concentrations of both ballistic and cruise-missile antiship weapons, the Chinese position appears formidable. China could at will declare the area to be official Chinese territory, establish an ADIZ, and pretty much shut the area down to anything but a full military response. From that point on, the South China Sea could serve as a base for power projection aimed at the smaller states of the region and beyond at China’s major rivals—Japan and the U.S.

China’s primary weapon for this theater is the DF-21D ballistic missile. With an impressive name translating as “Assassin’s Mace,” the DF-21D is an antiship ballistic missile (ASBM), a so-called “carrier killer.” Adapted from an earlier solid-fuel IRBM design, the DF-21D can be fired from a mobile launcher from just about anywhere along the coast of China. It has a range estimated at 1250 to 1850 miles (2000 to 3000 km), which means it can easily cover most the South China Sea. On launch, it is guided by independent Over-the-Horizon (OtH) radar, and then receives midcourse updates from drones or the BeiDou tracking satellite before switching to internal radar for terminal guidance. It is claimed to be fitted with a Maneuverable Reentry Vehicle (MaRV) which means that the warhead could conceivably outmaneuver missile defenses. The Circular Error Probable (CEP), the area in which at least half the warheads would land, is said to be on the order of 90 ft (30 m). An upgraded model, the DF-26, with a range of around 1850 to 2500 miles (3000 to 4000 km) was unveiled in 2015 and is probably entering the inventory.

DF-21Ds on parade. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

The DF-21D caused something of a panic when it became operational in 2010, as the latest of a long line of weapons guaranteed to render the carrier obsolete. In truth, if these missiles can live up to their reputation, they are a weapon to be reckoned with.

China also has a large array of antiship cruise missiles, both ground and air launched. Most are based on Russian or U.S. designs (including one transparently patterned on the U.S. Navy’s BGM-109 Tomahawk). But a few are of indigenous design. These include the CSS-N-1 Scrubbrush, which can be fired from a coastal site or a missile boat, with a range of 110 nautical miles (NMI). The CSS-N-5 Sabot, derived from the Russian Styx, which is fired from coastal batteries and has a range of thirty to fifty nautical miles. The CSS-C-7 Sadsack, another Styx variant with a range of 190 nautical miles, the CSS-C-6 Sawhorse, with a 110-mile range. Air-launched models include the CAS-1 Kraken and the CJ-10 Long Sword.

Chinese tactics involving these weapons are transparent. Chinese rocket forces would first use DF-21Ds to sink any carriers entering the South China Sea and then, utilizing the Spratlys and Paracels as unsinkable aircraft carriers, inundate the remnants of the task force with both air and ground launched cruise missiles. Only then, with the invading fleet’s air cover destroyed and missile/air defenses badly degraded, would manned aircraft enter the fray in order to pursue and sink any fleeing vessels. This attack might be thought of as a 21st-century version of the 1988 slaughter of Vietnamese troops in the Spratlys, with missiles rather than machine guns. The Chinese, if possible, would sink every last ship in a calculated and brutal act of force to discourage any similar efforts in the future.

Yet another threat exists: China’s impressive fleet of diesel-powered submarines could track and degrade a fleet even as it was approaching the South China Sea. While Chinese nuclear-powered subs are nothing to write home about, its diesel models are world-class. The danger of diesels lies in their ability to run much quieter than nuclear subs (which must keep reactor pumps constantly running) and are correspondingly more difficult to detect. China operates at least sixteen attack boats in its South Sea Fleet, along with twice that number in its other two fleets. Until recently, these were older Ming (Type-035) or Song (Type-039) class boats, but it’s likely these have been replaced by modern Yuan-class (Type-039B) hulls.

One thing we need not worry about is a Chinese carrier force, whatever that may consist of. At the moment, the Chinese are operating a single carrier, the Liaoning (CV-16), a modified Soviet-era Kuznetsov-class carrier bought from Russia. Though rated as combat-ready by the People’s Liberation Army Navy, the Liaoning can be viewed as a demo model, useful for training and gaining experience.

Currently two new carriers of indigenous design (CV-17, CV-18) are under construction with two more planned. Once these ships are commissioned, China will have a carrier fleet second only to that of the U.S.

But possessing and knowing how to use carriers is two different things. Operating carrier forces is an abstruse art, one that only two nations, the United States and Japan, have ever fully mastered. It’s unlikely that the Chinese, lacking experience and doctrine, will match this right out of the gate.

The Chinese situation regarding carriers is similar to that of Germany and its battleships during WW II. Lacking both support ships and experience in utilizing battleships, the Nazis chose a strategy of sending out its capital ships solo as glorified commerce raiders in an attempt to destroy Allied convoys crossing the North Atlantic. After the Bismarck was sunk on just such a mission (May 1940), Germany retained its surviving battleships, Tirpitz and Scharnhorst, in friendly ports (first in France and then in Norwegian fjords), utilizing them as a potential threat against Allied forces. (Scharnhorst was sunk in 1943, again acting as a commerce raider). It’s likely that China would select this alternative, keeping its carriers in port as a fleet-in-being rather than risking them in a mano a mano confrontation.

China also has a problem with its carrier-based aircraft. The model being fielded, the Shenyang J-15 Flying Shark, is unable to take off from the Liaoning with a full munitions and fuel load. Since the planned carriers are also ski-jump designs, this drawback is likely to remain in force. It’s difficult to see carriers going into action with such an Achilles heel.

As for air power, China is currently fielding the Chengdu J-20 fourth-generation fighter (as China insists on calling its fifth-generation fighters). Clearly patterned after the F-22 Raptor, the J-20 was designed as a match for U.S. stealth fighters. The first PLA units equipped with the J-20 were declared operational February, 2018.

It’s likely that the J-20—along with earlier models—will be armed with the Very Long Range Air to Air Missile (VLRAAM), with a range of from 250-300 miles. This missile is designed primarily to target support aircraft such as tankers and AWACS that act as force multipliers for U.S. air forces. These planes will no longer be out of range and immune from enemy action. Shooting them down would render any U.S. air campaign infinitely more difficult.

Clearly, the Chinese have created a formidable welcome for anyone attempting to trespass on Blue China once Beijing makes its expected move. It’s also clear, from the nature of the weapons themselves, that planning involving the South China Sea has been in play for decades. These weapons were designed and built with one opponent in mind: the United States and its Navy.

The U.S. Response

But it’s not often that military forces actually match what appears on paper. The heat of combat quickly boils away bogus claims and wish-fulfillment dreams, and that’s very likely to be the case here. We should not overlook the fact that the master strategist Sun Tzu was Chinese. The Chinese have not forgotten one of his prime dictums: “All warfare is based on deception.”

For instance, a closer look at the mighty DF-21D reveals that it has never been tested against a maritime target. Ground targets, yes, but a ship? Not once. This makes perfect sense—China’s entire maritime strategy is hinged on this weapon system. If it’s tested and it doesn’t work—and missiles, as we all know, are very finicky devices—their entire strategy goes up in smoke. What the Chinese need is a dark and brooding Sauron of a weapon looming balefully above Blue China. Why ruin it by testing the thing?

There is also considerable question as to whether Chinese electronics and cybernetics are sophisticated enough to handle the datalinks necessary for targeting the missile.

Antiship cruise missiles such as the Exocet and Styx have had quite a successful run for the past thirty years, but countermeasures have caught up and it’s unlikely they will be as impressive as in the past. It’s also a fact that many Chinese cruise missiles are relatively short-range, with target radiuses limited to from 50 to 200 miles. It would not require a lot of effort to stay out of their way.

As for China’s diesel boats, no one can argue that they aren’t crackerjack weapons. But China’s major sub base in the South China Sea area is on the island of Hainan, which is located on the continental shelf. Sea depths around the island range from 30 to 90 feet for quite a few miles out from the base. The South Sea sub flotilla would have to traverse what amounts a shooting gallery before going into combat and returning for refueling and resupply would be out of the question.

As for the J-20—this fighter may eventually develop into a challenge to U.S. stealth aircraft, but it’s simply not there yet. A major roadblock lies in the aircraft’s engines, the WS-10B, a Chinese copy of the Russian AL-31F Saturn, a 1980s design that’s several generations out of date. China’s own engine for the J-20, the WS-15, exploded during testing, and the Chinese have not been able to solve the problem, which involves cutting-edge alloy technology. Using the WS-10B has cut the J-20’s performance to fourth-generation fighter levels—it can’t achieve supercruise and requires an afterburner to accelerate to military power. As it stands, the J-20 is now easy prey for the F-22 or F-35.

So, like the Russian S-400 air defense system, which recently beschmucked itself in Syria after a decade-long superweapon buildup, the Chinese Goliath is neither as buff nor as fearsome as many have claimed. What would be the best strategy for the U.S. and its allies in turning back a territorial power play?

The chief term here is “allies.” The U.S. would not be going into combat against China either alone or with cobelligerents scarcely concerned about the outcome, as in some recent wars. The local powers clearly have serious interests in how matters fall out. In some cases, it wouldn’t be exaggerating to say that these amount to life or death.

Japan and Vietnam would play crucial roles alongside the U.S. in a war with China. We need not dwell on the irony that these two states were both bitter enemies of the U.S. within living memory. Both are serious regional powers, both have critical interests in the region, and both have well-earned reputations for military prowess. The fact that the U.S. would be sailing into battle alongside them is good fortune of the highest order.

Vietnam has long played the role of Ireland to China’s UK for nearly a millennium, with the Chinese regularly attempting to occupy the country and just as regularly being chased out. (A history that the U.S. might have read with profit back in the 60s.) The PRV’s role in a South China Sea conflict would be twofold: first, its army and air force would act as forces in being on China’s southeastern border, forcing Beijing to concentrate there rather than deploying to the main area of operations. Apart from that, while Vietnam’s fleet of Kilo-class submarines is far from state of the art, they would act as a definite threat to Chinese surface and submersible units, forcing them out of the Gulf of Tonkin and the southern reaches of the “Cow’s Tongue.” It’s far from impossible that Vietnamese subs could interdict Hainan (which is a little over 200 miles from the Vietnamese coast), preventing maritime forces based there from going into battle.

Japan’s initial role would be similar—using its missile installations in the Ryukus and the Senkakus and its fleet of Oyashio and Sōryū-class submarines to slam shut the northern door to the area of operations. The Japanese military could prevent China’s northern fleet units (This includes the Chinese carrier Liaoning, which would be unlikely to sortie in any case) and aerial assets from reinforcing the island bases. It could also seriously jeopardize Chinese naval units attempting to operate in the East China Sea.

The U.S., as is usually the case, will shoulder the main burden.

Though some analysts have envisioned a mad dash by carrier strike forces into the cauldron (a few have even imagined Littoral Combat Ships taking on the role of major surface combatants), this is far from necessary, much less advisable. Because if China has the Spratlys and Paracels, the U.S. has the Philippines.

U.S. Navy operations in the South China Sea will resemble those of the Central and Southwestern Pacific in 1942-1945. Rather than attack both island chains at once, U.S. forces would first move on the Spratlys, and once they were secured, only then go on to the Paracels. The Spratlys are a little over 200 miles from the Philippines.

This means that a U.S. naval strike force does not have to linger in the open sea in clear view of Chinese OtH radar, diesel subs, drones, and any other hazard that Beijing has dreamed up. Instead the U.S. can hunker down amid the islands. There it would be hidden from conventional radar by the island’s radar shadows. As for OtH radar, it operates by amplifying extremely small signals reflected from the ionosphere back to the receivers. Island clutter and temperature inversions created by the islands would be likely to complicate the process to the point of complete uncertainty. (There also exists surface-wave OtH radar, but this type lacks the range to be useful here.) Deprived of initial radar guidance, the DF-21D and all but air-launched cruise missiles would be rendered irrelevant. (Drones, which provide targeting data, would be unlikely to penetrate defended airspace in necessary numbers, and the Beidou military satellite can be easily be spoofed.) As for China’s diesel subs, anti-submarine (ASW) resources could plug the channels leading out to open sea with much more confidence than on the high seas.

In effect, the Navy would be converting the islands into the equivalent of fortresses much larger and more capable than those of the Chinese. (All this, of course, in contingent on Duterte or his successor allowing U.S. naval units into Philippine waters. But we shouldn’t forget that most Filipinos avidly support the U.S. and distrust China.)

Another possible action would be mining the approaches to Hainan, to assure that Chinese diesel subs still in port could not intervene. Mining is an effective tactic that is often overlooked. Mines dropped from B-29s sank much of what remained of the Japanese merchant fleet in the last months of WW II, effectively isolating the Home Islands. A handful of mines shut down the Caribbean approaches to Nicaragua in 1984. Such a minefield could be laid either by U.S. Navy assets or by Vietnamese Kilo subs.

Once the carrier strike force is in place, the campaign would open up with B-2 Spirit strikes against major installations in the Spratlys and Paracels. We should assume that both Anderson Air Force Base on Guam and Kadena Air Base on Okinawa will have been disabled by DF-21 strikes, so the raids would originate from either the continental U.S. or Hawaii. While much has been made of the abilities of Chinese long-wave radar to detect stealth aircraft, this largely applies to smaller planes like the F-22 and F-35, which have features (the tailplanes, e.g.) which nearly match the radar’s wavelength. B-2s have no such features and remain difficult to detect.

These strikes would lay down heavy conventional bombs on runways and cruise missile sites, along with Anti-Radiation Missiles (ARMs) launched against radar stations, including those on the mainland. The raids would be supported by cyberwarfare to cripple China’s C3I capabilities, both in the islands and on the mainland, along with satellite assets in LEO.

At the same time U.S. stealth fighters could begin sweeps above the islands. This is where the F-35 Lightning II would come into its own, particularly the USMC’s VSTOL F-35B variant. While China could conceivably knock out most of the airfields in the region, the F-35B could operate from small strips virtually anywhere in the Philippine archipelago, as well as bases in Vietnam. Palawan, in particular, the long southern island reaching almost to Indonesia, would be a perfect staging area. (Interestingly, the Japanese based some fighter-bombers on the island before their assault on the Philippines in 1941.) Marine stealth fighters appearing from all directions would complicate China’s air strategy almost impossibly.

Palawan is only minutes away from the Spratlys, allowing even the relatively short-legged F-35s a useful period over the area of operations. This would also render tanker support not strictly necessary in the early stages of the battle. (On the other hand, the Navy could well be operating the MQ-25 “Stingray,” a stealthy drone tanker, in the near future.)

AWACs might still be able to operate in the face of Chinese VLRAIMs by “stuttering”—taking a “snapshot” of activity, analyzing it and forwarding the results to combat aircraft, and then minutes later taking another snapshot from a different position. The aircraft could drop to low level, hiding behind land features (There are plenty of mountains in the Philippines, fortunately) between shots.

Arming AWACS and other support aircraft is long overdue—they could easily carry and launch both radar and infrared AIMs for self-defense. The F-35s networking capability, by which aircraft can share realtime tactical information, can also go a long way toward replacing AWACS.

With the Chinese garrisons cut off and isolated and local air superiority assured, landings could occur. The Spratlys are within striking range of V-22 Ospreys and Marine LCACs operating out of the Philippines. The LCACs would depart first. At forty knots it would require the hovercraft 5-6 hours to reach their targets. The V-22s could take off several hours later, bypassing the hovercraft a few miles from the beaches so as to spearhead the assault. The Marine attack would be accompanied by a full press of other assets—cyberattacks, EW operations, and air and missile strikes—to assure that the vulnerable hovercraft and tiltrotors were not intercepted.

The Marines could take the target island, destroy whatever needed destroying, and then hunker down to await a counterattack. One necessary cargo for the LCACs would be Patriot ABM systems to deal with Chinese ballistic missile strikes. It’s not unlikely that the PLA might choose to barrage the islands in much the same way as WW I Imperial German Army artillery did its forward trenches when they were lost to infantry attacks. Alternately, the Marines could clean up the island, pack any prisoners into the hovercraft, and take off for a nearby island which the Chinese would be uncertain was occupied. They could then blast the first island as much as they liked.

It wouldn’t be necessary to take every last glorified sandbank. Updating the WW II “wither on the vine” strategy, securing only the major islands and letting the others hang would work.

With the Spratlys under control, the carrier strike force might now enter the battlespace, perhaps accompanied by Japanese helicopter carriers of the Hyῡga-class, along with the larger Izumo, and perhaps even naval units of the smaller powers. With the cruise-missile threat eliminated, they might rendezvous at the Spratlys to prepare the assault on the Paracels.

A classy gesture at this point would be to present Beijing with an ultimatum: avoid damage, casualties, and humiliation involving their inner island fortresses. China could surrender them to international control, with the final outcome left to negotiations under UN rules. In a sane world, this would end the whole affair. But the Chinese have invested so much in the way of resources, effort, and national identity and pride in the region that they would be far more likely to choose to go down fighting.

Regarding the Paracels, Woody Island would present a special case with its large civilian population, perhaps swelled by the presence of tourists. It might be wise to avoid taking the island itself, instead settling for crippling its installations. The rest of the Paracels chain should be straightforward.

What about repercussions on the U.S. home front? There would no doubt be cyberattacks—the Chinese have been preparing for these for years. But after a prolonged stupor, the U.S. has begun working on countermeasures (we no longer hear about “smart meters’ for gas and electric utilities, which would have allowed third parties—including Chinese “Blue Army” cyberwarfare teams—to control utilities across the country.) No nuclear attack would occur—it simply wouldn’t be worth it. In particular, there would no EMP strike such as the more hysterical policy analysts have been shrieking about in recent years. Talk to an experienced electrical engineer about EMP. Starfish Prime, the 1962 nuclear shot that introduced the world to EMP, has been grossly misrepresented. Its effects on Hawaii amounted to 300-odd burglar alarms going off, the phone system partially down, and a few street lights shut off. No exploding transformers, no power lines melting, no return to the 19th century. We can keep EMP out of our calculations.

Could a South China Sea war go in the other direction? A complete fiasco for the allies, leaving China poised like a colossus above the Western Pacific? Of course it could. War is the kingdom of uncertainty. When you open the door to conflict, you never know that’s going to come leaping out at you. The breaks could all go China’s way. The allies could hamstring themselves with politically correct policies and rules of engagement, handing the initiative over to Beijing. (The Vietnamese could tell you how this works out.)

But it’s not likely. China is facing a nearly united front against its actions. It is gambling on new and untried weapons systems. It is utilizing methods of combat it has not practiced in centuries (the last time China operated a navy was in the 1470s.) It is up against two effective and competent regional powers and the world’s reigning superpower. It is facing, as previously mentioned, the two major maritime powers of the modern era, both of which possess unmatched experience, tradition, and doctrine for facing the kind of challenge the Chinese have mounted. The PRC also has a potentially fatal Achilles heel produced by its own system. Its officers and men are all products of an authoritarian communist state, one that still retains more than a touch of its previous totalitarian nature. Virtually all of them will be victims of what social psychologists call the “compliance mindset”: that individuals have a minimal amount of capability, that the group is always right, that orders are orders, that initiative and imagination are dangers that must be avoided. Once the chain of command is broken, the Chinese will face a serious danger of overall paralysis. Sun Tzu would not have approved.

As it stands, some kind of confrontation is shaping up. China is throwing its weight around, violating international norms, bullying small neighbors, and no one has drawn the line. It has achieved a dominating position in the South China Sea without any visible cost. Classically, an authoritarian state in such a position does not turn back. China’s actions today are similar to those of Saddam’s Iraq in the years before the First Gulf War.

This is where writers come in. One of the reasons China has been able to pull this coup off is the ignorance of the Western world. The third millennium has introduced a new and unfamiliar form of insularity. What was once caused by ignorance is today caused by a surfeit of information, a fog of data that clouds pretty much everything outside of the everyday. The result is a citizenry that knows even less about what is going on in the world than previous generations of the newsprint era did. The public in the late 30s were well aware that Imperial Japan was on the rampage in China and East Asia. Most Americans today do not have the vaguest notion that anything is wrong in the Western Pacific.

This can’t be allowed to prevail. This country’s citizens need to be reminded, to be informed, and in a word, to be woken. Consensus in a democratic polity cannot exist without dialectic and discussion. Writers, filmmakers, and artists of all sorts must act as triggers for that discussion. It’s part of the price asked of us—and properly so—for the lives of freedom and nonconformity that we’re enabled to live. Artists of the 30s in the UK, France, and the U.S. fell down on their responsibility to warn and give guidance where the totalitarian states were concerned. We know how that worked out.

We don’t need to start out the new millennium in the same way. The media will not do the job, the academy will not do it, so it’s up to us. Let’s power up our keyboards and get to work.

Bibliography:

Asia Times Staff, “US aircraft carrier Vinson, Japanese Navy drill in South China Sea” Asia Times, March 14, 2018

BBC, “Why is the South China Sea contentious?” July 12, 2016

China Power Team, "Does China’s J-20 rival other stealth fighters?" China Power, February 15, 2017

Dillow, Clay, “Military nightmare scenario brewing in the East China Sea” CNBC.com, April 4, 2017

Ebbighausen, Rodion, “South China Sea dispute - Long way ahead for China, ASEAN” Deutsche Welle, May 5, 2017

Eckstein, Megan, “Vinson Strike Group Makes Historic Port Call in Vietnam Amid Growing Navy Ties, South China Sea Tensions” U.S. Naval Institute News, March 6, 2018

French, Howard W., “What’s behind Beijing’s drive to control the South China Sea?” The Guardian, July 28, 2015

Glaser, Bonnie S., “Conflict in the South China Sea” Council on Foreign Relations, April 7, 2015

Globalsecurity.Org. DF-21 / CSS-5 [ SC-19 / KS-19 ASAT ] DF-21C /CSS-5C

Global Security Org. “Spratly Skirmish—1988”

Gomez, Jim, “Navy says it won't be deterred by Chinese-built islands” Navy Times, February 17, 2018

Holmes, James R., “Defeating China's Fortress Fleet and A2/AD Strategy: Lessons for the United States and Her Allies” The Diplomat, June 20, 2016

Hunt, Katie, “South China Sea: Court rules in favor of Philippines over China” CNN, July 12, 2016

Kaplan, Robert D., “The South China Sea Is the Future of Conflict” Foreign Policy, August 15, 2011

Kazianis, Harry J., “Is China's "Carrier-Killer" Really a Threat to the U.S. Navy?” National Interest, September 2, 2015

Keck, Zachary, “Japan May Place Anti-Ship Missiles on Okinawa. And the Reason Is China” National Interest, March 3, 2018

Kuntz, Jonathan W. “Japan’s Military Provides America with New Strategic Options” National Interest, November 1, 2017

Lendon, Brad, “Chinese stealth fighters are combat-ready, Beijing says” CNN, February 11, 2018

Lendon, Brad, “Mattis: US will defend Japanese islands claimed by China” CNN, February 4, 2017

Majumdar, Dave, “Here Is Why the US Military Is Not In Panic Mode Over China's Carrier-Killer Missiles” National Interest, June 20, 2016

McCurry, Justin, “Japan steps up military presence in East China Sea” The Guardian, December 18, 2015

Miranda, Miquel, “The Ambiguous War Over the South China Sea” Cable Magazine, February 1, 2018

Pesek, William, “Making Sense Of the South China Sea Dispute” Forbes, August 22, 2017

Tata, Samir, “China's Maritime Great Wall in the South and East China Seas” The Diplomat, January 24, 2017

Scimia, Emanuele, “Japan's East China Sea Military Buildup Continues” National Interest, May 6, 2016

Wong, Catherine, “China’s rising challenge to US raises risk of South China Sea conflict, Philippines warns” South China Morning Post, February, 2018

Xu, Beina, “South China Sea Tensions” Council on Foreign Relations, May 14, 2014

Yoshihara, Toshi, “The 1974 Paracels Sea Battle. A Campaign Appraisal” Naval War College Review, Spring, 2016

Copyright © 2018 J.R. Dunn

J.R. Dunn is the author of science fiction novels This Side of Judgment, Days of Cain—widely hailed as one of the most powerful time travel novels to deal with the Holocaust—and Full Tide of Night. Most recently, he’s the coauthor, with Robert Conroy, of alternate history The Day After Gettysburg. He’s also the author of nonfiction book Death by Liberalism, and many nonfiction pieces. Dunn was the long-time associate editor of The International Military Encyclopedia and is now an editor at The American Thinker.