Do You Believe in the Singularity? by Dr. Robert E. Hampson

The singularity. Many Science Fiction writers and futurists postulate a future when humans have assisted their own evolution with genetic engineering, cybernetics, and prosthetics such that they are no longer human. This definition for human singularity is often (mis)attributed to inventor Ray Kurzweil, a proponent of technological advancement that can—even will—result in fundamental transformation to something so different that those creatures would no longer be recognizable to us mere primates as being human.

An SF convention panel asked the question: "Do you believe in the singularity?" It shocked the panel that a neuroscientist and SF writer, a person who works on developing the means for humans to transcend physical disease and limitations, would answer "No." So perhaps it would be more appropriate to title this essay: "Why I don't believe in the Singularity." There are many answers—the first involves the very definition of singularity from both the biological and the classical physics points of view. From there, the reasons progress from an in-depth understanding of the human brain and body to end up with discussions of what it means to be human. These are discussions that take center stage in both my fiction and nonfiction writing, and I am at heart an optimist (and human-centrist), so I was delighted when Baen Books invited me to take the time to explain my fundamental faith in humans and why I think that humans will inherit the stars.

Definition

Mathematics:

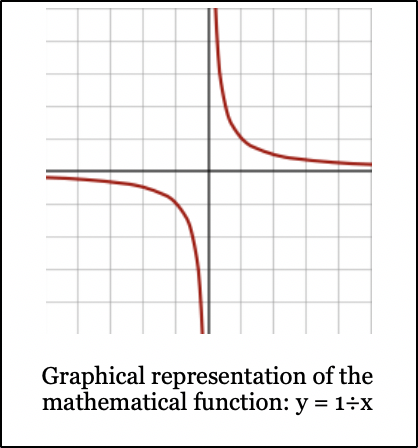

The simplest explanation of singularity comes from mathematics, as illustrated by the image below:

This graph shows the results of "dividing by x" where every possible value of x results in a valid outcome except for when x=0. As values of x approach 0, y approaches infinity. When x=0, y cannot be calculated or defined. By some definitions, the result is infinity, but in practicality, the result is unknown and undefined—a singularity.

Note that reading the graph from left-to-right or right-to-left, there is a discontinuity at x=0; i.e., it is not possible to graph a continuous function along the horizontal axis. Thus, using the mathematical analogy, a human singularity could be a discontinuity in the evolution of the human brain or body, beyond which it is not possible to extrapolate the new form from what has come before.

There's more to the notion of human singularity than this, but we'll move on to another definition, first.

Physics:

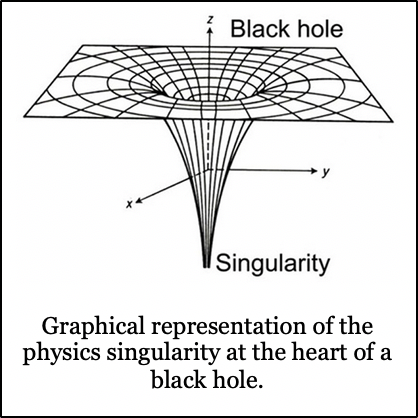

The physics definition of a singularity is quite similar to that of mathematics—namely, a point where physical observation breaks down, as illustrated by the classical space-time graph of a black hole:

There are many aspects of cosmology and physics that represent the singularity of a black hole. For example, there is the event horizon which delineates the region in which the escape velocity for photons exceeds the speed of light; hence, an electromagnetic singularity is formed. A second type is that of gravity, where the singularity exists in the zone where gravity is so intense that no physical matter can survive. Finally, there is the space-time singularity where the curvature of space is such that the physical constants of "flat" space simply do not apply.

In all of these cases, the singularity consists of a point that cannot be observed, measured or described using the physics that exists outside the singularity. We have no idea what exists on the "other side" of a singularity.

Biology:

Physiological and genetic references to singularity generally involve humans "assisting the evolution of the human form via biological engineering, prosthetics, cybernetics, and human-machine integration such that the resulting creature is no longer recognizable as human.” However, the biological model of singularity is typically applied to intelligence and follows the prediction of British (later American) mathematician I.J. Good, who predicted what he termed an "intelligence explosion" (Speculations Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine, 1965). The "explosion" results when a highly intelligent "agent" (i.e., computer) designs even more sophisticated agents with the potential to far surpass the sum of all human intelligence. Like the mathematical and physical singularity, the singularity consists of that inflection point beyond which mere human intelligence cannot even conceive of the resulting artificial intelligence.

Popular Usage

Even though the concept of a biological, nay human, singularity is attributed to Ray Kurzweil in his 2005 book The Singularity is Near, the idea is much older. John von Neumann was the first to use the term "technological singularity" to rapid and ever-accelerating technological development. SF author Vernor Vinge, heavily influenced by von Neumann and Good wrote in a 1983 Omni op-ed of "an intellectual transition as impenetrable as the knotted space-time at the center of a black hole." While he did not explicitly call it a technological singularity, he later did so in the introduction to his short story "The Whirligig of Time" [Threats and Other Promises, Baen, 1988]: "When we raise our own intelligence and that of our creations, we are no longer in a world of human-sized characters. At that point, we have fallen into a technological ‘black hole,’ a technological singularity."

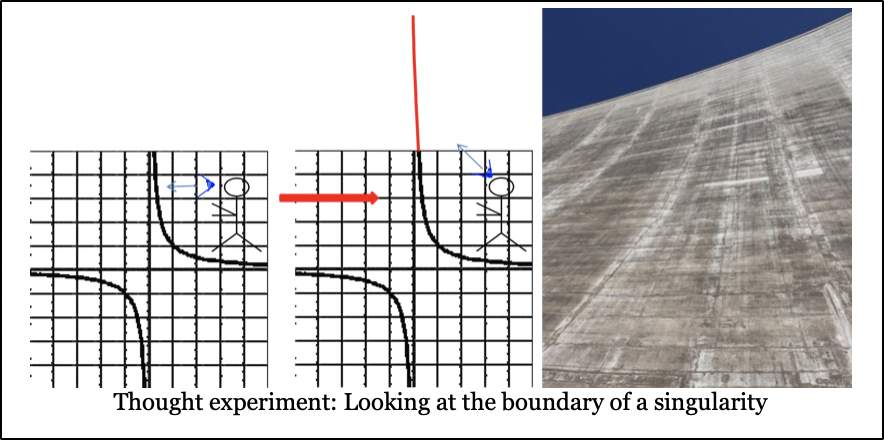

To understand this manifestation of the term singularity, imagine standing on the right side of the y=1÷x graph above:

As you look at the upward curve of the plot and continue to look upward, it becomes an infinite wall that cannot be scaled, crossed or penetrated. Whatever is on the other side cannot be seen or even imagined. To futurists like Kurzweil, Vinge or Good, the human singularity is a point at which change is so rapid, faster than the ability to comprehend that there even is change, that it might as well be a wall separating the merely "human" Homo sapiens sapiens from our replacement H. sap. superior.

While some might argue that any evolutionary improvement of the human body could contribute to some form of singularity, both Good and Vinge say that the critical ingredient is the development of super- or ultra-human intelligence. It should also be noted that Vinge's interest in the singularity is quite firmly anchored in SF, given that his primary concern was the impossibility for a writer to generate convincing post-singularity human characters since it was not possible to understand any of the characteristics that his audiences could comprehend.

In that case, we might as well treat post-singularity humans as aliens.

Transhumanism

The concept of the transhuman or superhuman is also not a new one. It's also a complicated history and usage with many negative connotations such as eugenics, so I'll not delve into the full derivation of the term(s) here. Instead, let's look at general cases and how they are used in SF. Essentially a transhuman is one that has been "improved" by pharmacological, cybernetic and genetic means to have capabilities far in excess of the average human. One of the most influential books for my own career was Cyborg by Martin Caidin. This novel, from which the TV show The Six Million Dollar Man was derived, popularized the idea of prosthetic limbs that not only restored human abilities but added superhuman speed, strength, and agility. David Weber's popular heroine Honor Harrington is a superhuman, with longevity treatment that keeps her young, improved durability, and an genetically manipulated metabolism that allows her to eat what she wants and maintain fitness without exercise! John C. Wright's Count to a Trillion shows us a human who was already quite smart, then modified his brain chemistry to give himself an intellect that is so far advanced that mere humans seem little more than animals.

How much of this is real, and how much merely fiction? Is there a possibility of creating or evolving humans into a superhuman state? An interesting dichotomy between Caidin’s Cyborg and the Six Million Dollar Man was that Caidin proposed the "bionic" legs and arms, but not the bionic eye (or ear from The Bionic Woman). In this, Caidin was mostly correct in that as of 2019 there are effective prosthetic limbs for legs, arms, and hands, but not so much for vision and hearing (at least in the manner shown on TV). Within the last five years, we’ve seen incredible advances in brain-controlled upper limb prosthetics (see my Baen Free Nonfiction article “Fixing Broken Memory.” The eye and ear prosthetics are still in very early days. On the other hand, we also have drugs that facilitate focus and cognitive ability, such as Provigil and aniracetam.

The problem is that none of these items, prosthetic or pharmacological, provides the superhuman ability proposed by the transhuman and singularity enthusiasts. Lower limb prosthetics are still primarily passive, consisting mainly of springs and clockwork with no tactile sensation, no balance feedback, and limited ability to adapt to changing terrain. Upper limb prosthetics are limited by weight, and the tactile sensation is still under development. Despite the promises of the movie and TV show Limitless, the cognitive enhancing drug aniracetam has so many side effects and contraindications, that its use is severely limited, and can even result in death or brain damage.

The issues listed above don't address genetic engineering. A recent news article cited the work by a Chinese researcher to gene-edit embryos intended for in-vitro fertilization treatments here. The announcement was immediately greeted with uproar, followed by condemnation of the researcher, sanctions against his original U.S. university, and even colleagues under suspicion of providing U.S. Government-funded intellectual property to the experiment. Society as a whole might be willing to tolerate minor edits to fix a congenital disability, but the study under fire edited a disease resistance trait that had no immediate benefit to the children born from the procedure. Transhumanism has a long, hard path to climb.

Being Human

To me, there are several issues with singularity and transhuman concepts. The first is that somehow as we progress with bionics, pharmacology and gene editing, that we will somehow lose what it means to be human. As I usually inform people in talks about my research, it is our memories that provide an essential feeling of “self.” As long as we have memories of being human, we are human. Hence, as long as there is still a human core to the individual who has been patched up, rebuilt, cured and enhanced, the singularity has not yet occurred since we can always trace the path from unaugmented to augmented human.

Likewise, as we move our human civilization off of Earth to other planets and even star systems, we face the questions of whether to transform our environment to suit humans (at significant monetary and material cost and difficulty) or to change ourselves (at high societal cost) to fit the situations we encounter. If I may be permitted a book plug, these are precisely the questions asked in the anthology Stellaris: People of the Stars, a September 2019 Baen book. In that volume, co-editor Les Johnson and I collected stories from authors who explore themes of what it means to be human. The stories range from Sarah A. Hoyt's "Burn the Boats" in which colonists may be giving up their humanity to survive, to Brent M. Roeder's "Pageant of Humanity" which presents a unique view on deciding just who is, and who is not, human.

To make the jump to gene-tailored humans will require scientists, ethics boards, and the rest of society to work hand-in-hand to decide what and how much gene editing will be allowed. As with the recent news case, some commentary suggests that fixing defects is fine, but aside from that, gene editing humans should be forbidden. That will likely change in the future, but we don't know when. On the other hand, when it does, we will definitely face the prospect of a new human subspecies (or even species), but it will not take the form of the singularity as proposed by Kurzweil, Good, and Vinge, but as a speciation event such as has occurred countless times throughout the history of life on Earth.

Artificial Intelligence

What of the underlying fear of the futurists that humanity will be supplanted by a superintelligence, either machine or biological? Tech billionaire and entrepreneur Elon Musk is on record as stating that many of his technological endeavors arise from the concern that artificial intelligence could supplant humans. Kurzweil proposed that as computers become more complicated (100 million processing elements = one human brain in his writings), artificial intelligence could arise, and take a hand in its own development and enhancement. AI developing the next generation AI, as described by Vinge, would create a superintelligence that meets the definitions of singularity, with a rate of change that approaches infinite and beyond the understanding of mere human intelligence.

There are several problems with the concepts of AI as superintelligence . . . at least as compared to the current understanding of the human brain. Kurzweil's estimate was too low by at least six orders of magnitude. His assessment of the number of neurons was too small by three orders of magnitude; the human brain contains approximately 100 billion neurons. Since computer scientists like to compare processors to neurons, it’s not unreasonable to predict computers having 100 billion processing elements given current technological trends.

Unfortunately, single neurons are not the basic processing unit of the brain. Depending on an individual neuroscientist's bias toward their field of study, researchers consider either the synapse (between neurons) or the neurotransmitter/receptor pairings in a synapse, as the primary processing unit of the brain. There are typically thousands of synapses per neurons and can be hundreds to thousands of neurotransmitter packets released into a synapse to bind with the receptor proteins. This yields from 100 trillion to 100 quadrillion processing elements if a computer is intended to mimic the capability of a human brain. And if it is matter of numbers.

But what about AI now? We have seen marvelous claims of AI capabilities from Google’s search engines to Siri’s speech recognition. Surely we have at least a rudimentary synthetically generated intelligence serving us now? (Although to be honest, I somewhat prefer Vonda McIntyre’s term “Artificial Stupid.”)

Not really.

At the DARPA60 conference last September (2018), there was much talk about the current state of AI. What we currently have is certainly artificial—in the form of computer programs which process information—but it is far from intelligence. In an article in Psychology Today (Nov 28, 2018), Dr. Neel Burton provides a dictionary definition: "the ability to think, reason, and understand instead of doing things automatically or by instinct." (Collins English Dictionary) and his definition of basic intelligence “. . . the functioning of a number of related faculties and abilities that enable us to respond to environmental pressures.”

The unfortunate limitation of Dr. Burton’s definition is that by “responding to environmental pressures,” even plants and animals show traits of intelligence. Moreover, the well-documented difficulties of elderly dementia patients in adapting to altered circumstances would have us conclude that such individuals are not intelligent.

Burton's article progresses from an inadequate definition of intelligence and into a degenerating criticism of IQ tests and the futility of equating intelligence with reason and analysis. However, what I feel we can take away from the article is the second dictionary definition he cites: “. . . the ability to understand and think about things, and to gain and use knowledge." (Macmillan Dictionary). From these concepts we can perhaps create our criteria for intelligence:

(1) detect and react to the environment (i.e. ". . . respond to environmental pressures . . ."),

(2) adapt to (or learn from) changes (i.e. ". . . gain and use knowledge . . ."),

(3) to reason, think about or understand the knowledge gained (i.e. “. . . the ability to understand and think about things”).

I chose three criteria to correspond to what the speakers at DARPA60 referred to as the three phases of AI development. Phase I was getting computers to interact with humans and look up information. Essential computer programming, look-up tables, expert systems, and input-output have all been part of AI Phase I. Phase I is all around us, from Google searches to the dreaded “press one for sales, two for customer service” phone trees used by businesses.

We are currently in the maturation part of Phase II, with speech recognition, face (and image) recognition, and "learning systems" that optimize their interpretation and retrieval systems. Voice assistants such as Siri, Alexa, and Cortana require minimal voice training and can interpret commands and retrieve information. Facial recognition can secure your computer, tablet or phone, and image processing software performs multiple functions ranging from reconnaissance to detecting copyright infringement. These interfaces give the illusion of AI, but at heart, the underlying programs are still expert systems equipped with a comprehensive list of criteria in lookup tables utilized to complete an automated function. Note how closely this compares to the exclusionary criterion in the Collins English Dictionary ". . . instead of doing things automatically or by instinct . . ." Current generation AI systems return the same result when presented with the same input. Oh, the programmers may get smart and include functions that point to a limited number of "random" responses, but if you could see the underlying program code and data, you would see the same result every time.

We are poised at the cusp of Phase III AI, generating programs that at least give the appearance of thinking or reasoning abilities. The next push in AI development is to combine the data retrieval of Phase I with the interfaces of Phase II and the ability to truly learn and interpret. The limitation so far has been that such programs still show evidence of automation: witness the "Deep Dream" photo pattern analysis AI from Google which seems obsessed with finding eyes and puppy-dog noses in every picture, or the Google and Facebook algorithm that keeps showing you ads for items you've already bought.

We're just not there yet, and even when we do get a real synthetic intelligence, it will still be a long way from humanlike. For one, there's the problem of duplicating the human brain with its quadrillions of processing elements, and then there's the issue of reproducing the human growth and learning experience which shapes our experience and reasoning.

I think AI is possible, but I hesitate to say what form it will take. I love the approaches taken in several recent books: In Ellay (formerly City of Angels) by Todd McCaffrey, nascent AI starts in an infantlike state and learns rapidly. Like a child, the titular AI imprints on a person. Fortunately, it's a genuinely good person, and the AI develops an altruistic streak and forms a partnership with several humans. In Today I am Carey, Martin Shoemaker posits AI as caretaker, who mourns the brief lifespans of his human companions. I think AI will be what we, as humans, make it; personally, I hope they are friends, rather than slaves or overlords!

Do You Believe?

Thus, it all comes down to what you or I believe about the singularity. My position is that as long as there is a direct trace of humanity, there is no singularity. From a biological point of view, it is possible to change the human body so that it no longer resembles what we know as human. However, as long as the genetics retain the same basic codes and the result can interbreed with humans, they are human. Otherwise, they are a different species, which is not a singularity at all.

Likewise, enhancing human forms with prosthetics and cybernetics still retains essential biology up to the point where scientists learn to download human intelligence into computers. Computers could potentially be inhabited by naturally derived or synthetically derived intelligence; however, as long as that intelligence has a memory of a human body, we would still consider it human. In contrast, synthetic or artificial intelligence is a new species. Once we make that jump, the general concept of singularity does not apply. The referenced intelligence was never human in the first place, and may never be understood by humans, making the definition of "rate of change beyond understanding" a moot point.

What about enhancing human intelligence? Certainly, all this talk about neural prosthetics will result in enhancements? If you talk to researchers in the field, you hear a familiar refrain: "We're not doing that, we're working on restoring lost function." It's true, as one of "those researchers" I can reiterate that our goal is fixing what's broken. We're concentrating on that first, and dreams of enhancement are just that . . . the ideas of people other than us.

Frankly, most neuroscientists don’t think we can enhance human cognitive abilities too much past the current state. We can allow a person to stay alert and pay closer attention (with amphetamines and Provigil), remember better (with memantine and aniracetam), and work a little bit faster (again, aniracetam and other nootropic drugs). Still, all of those functions add up to abilities shown by some of the more extreme talents in human history. Can we make everyone a Hawking, Nash, Mozart, Picasso, etc.? We might enhance the ability, but the human mind remains shaped by experience and environmental factors. Furthermore, the old trope "we only use 10 percent of our brain [power]" is false. Human brains are 100 percent active all the time. The activity is not always directed to the functions we term "thought" or "intelligence," and when it is, it still only makes up a small portion of the total neural activity at any given time.

So no, I don’t believe in the singularity—at least not the human/biological one. Not in the sense of humans changing so rapidly that we can no longer detect, let alone keep track of the changes. I also believe that the continuity of what we know as “human” will be retained for as long as possible, again defeating the popular concept of the singularity in producing such a change that the subject no longer considers themselves human.

When it comes to downloaded human intelligence and Artificial Intelligence, the jury is still out. I know that the ability to store and mimic the human brain is still many iterations away. What is popularly called AI is well within the realm of computer programming and does not truly think for itself. However, without explicitly duplicating the environment and experience of a growing human, the resulting creation is not going to be human intelligence. Perhaps if we grow it, we’ll approach something humanlike. Otherwise, it is a separate species, and not a singularity at all.

I do believe that rapid changes are on the horizon. Some of the concepts of singularity may well come true, and I’ve just “rules lawyered” them away by quibbling over definitions. Still, my argument boils down to this: I believe in humanity, and think that we will remain human as long as we (and others) believe that we are human.

Copyright © 2019 Dr. Robert E. Hampson

Scientist, author, educator Dr. Robert E. Hampson turns science fiction into science. He advises SF/F writers, game developers and TV writers on neuroscience among many other scientific matters. In his day job, Hampson’s research team developed the first prosthetic for human memory using the brain's native neural codes. Hampson and fellow Baen author and space scientist Les Johnson are the editors of anthology Stellaris: People of the Stars (Baen, Sept. 2019), a look at the physiological, social and technological changes that will be wrought on human beings as we explore and colonize space. He is a member of the futurism think-tank SIGMA, and the Science and Entertainment Exchange, a service of the National Academies of Science. For more information, including links to prior Baen Free Nonfiction, see Hampson’s website here.