The World of Ringer: Living in Saturn’s Rings by Andy Presby

A very wise woman once told me that it is easy to edit away an author’s heartfelt motivation for writing her story. The part of it she may not be able to put into words, which is the whole reason she’s writing the 100,000 word novel in the first place. She was so smart I married her and a benefit of that is that I occasionally get to help provide ideas for her stories.

I don’t aim here to try to tease out all the things Joelle was trying to say in Ringer. My goal as a guy whose primary creative activity is worldbuilding is to explain some of the reasons this setting speaks to us and some of the Real World ™ science and engineering that defines the spinning tuna can shaped world the characters inhabit. That world is a space station named Chawla and we’ll talk a little bit below about how and why it might all work once we get around to building something like it.

The germ of the Ringer of course began with Joelle’s previous book, The Dabare Snake Launcher. That book takes place several generations before the events of Ringer and tells a piece of the story of how humanity started moving out into the Solar System in a big way in the early part of the next century or so. Dabare established that an international cast of characters had invented the technology needed to build a space elevator on Earth and actually pulled together the money, the team, and necessary permits to make the whole thing happen. The story focused on the small part of that team that had the thankless job of clearing Earth orbit of over a century of hypervelocity debris that would have been a threat to the elevator. See Kim Stanley Robinson’s Mars trilogy for an object lesson in why you don’t want your space elevator to get cut. This story established some of the technical backstory that we’re taking forward into Ringer. Humanity has a much larger number of space stations and lunar outposts than we do today. Life support systems are more reliable and better at recycling air, water, and other materials needed to keep crews alive. Big commercial launch vehicles a la SpaceX’s Starship and Blue Origin’s New Glenn are an old reliable mainstream technology all over the world at this point. We have perfected magnetic rail levitation and can build rockets that can scoop some of their fuel from the atmosphere as they go. This combination permits the construction of rail assisted launch vehicles making modest small single stage to orbit uncrewed cargo spacecraft possible. All these propulsion systems, amazing as they are, are dwarfed by the space elevator’s potential to lift big masses to orbit more cheaply than a rocket can. The main inventions that make this possible are all in materials science and we grouped them all under the name “Diamond Wire” in Dabare. They imply a set of carbon-based nano materials able to be made at enormous industrial scales to permit things like huge cables going straight from the ground all the way to geostationary orbit.

All of these technologies (and many more that have to go unmentioned to keep a story readable) would give us incredible capability way beyond what we have today. They would allow humanity to move out into the Solar System in a much bigger way than we currently do. Ringer comes in several generations down the line and looks at where people went and how they might live once they got there.

Why Would Anyone Want To Live in The Rings of Saturn?

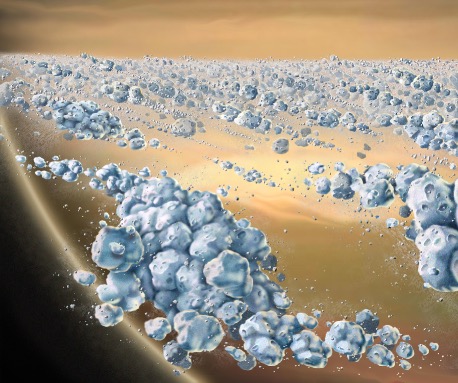

I fell in love with Saturn’s Rings looking at the pictures that came back from NASA’s Cassini mission to that planet. I mean come on . . . what’s not to love?

Figure 1: Saturn’s Rings Taken by Cassini. The Sun is behind the planet and Cassini was in its shadow. Original photo and more information here: Catalog Page for PIA08329

There are lots of features of the Saturn system that make it a wonderful setting location for fiction. I won’t give them all away in hopes that we’ll get to write more of them up in future installments of the series, but I’ll just tease two. First, the Rings are of such a scale that you can traverse them with Apollo-era chemical rocket technology in days or weeks . . . they’re big . . . but not too big. Second, you remember all those Hollywood asteroid belts with ships swooping in and out around house sized boulders?

Yeah.

Those pretty much don’t exist anywhere in the real world.

But ring systems like Saturn’s are pretty close.

No spacecraft has ever actually slowed down and gone into orbit in the Rings but between a variety of astronomical observations, images from space probes, and computer simulations we can get things like the artist’s concept below.

Figure 2: Artist’s impression of what it would be like in the Rings. Image by Marty Peterson, based on a 1984 image by William K. Hartmann. Hartmann’s image illustrated early research by Stuart Weidenschilling and co-workers at the Planetary Science Institute, on dynamical ephemeral bodies in Saturn’s rings.

As soon as I learned this (and I’m not even breaking out the best stuff) I was hooked and started thinking of reasons to set up stories in the Rings. I pretty quickly decided that there were so many interesting features that having people actually living there could serve as a backdrop for many stories. So I started looking for reasons one might want to live there.

Looking around for places to live you might conclude with NASA, Roscosmos, JAXA, pretty much every other space agency and Jeff Bezos that Earth is by far the best planet.

You’d be right.

But what if you wanted to get out of near-Earth space because you thought the neighborhood was really going downhill? Maybe you were feeling a little iffy on the neighbors. Maybe the economy was poor. Maybe you just wanted to see new things. Maybe you just wanted to be left alone for a while.

Looking for a place to live beyond Earth means looking for a good supply of water and other resources needed for life in a place where the natural space environment won’t make life prohibitively expensive.

It turns out that the Rings of Saturn fit that bill pretty well.

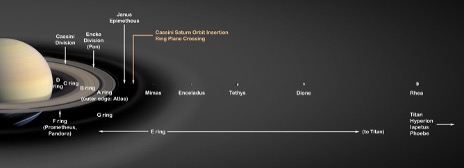

Figure 3: Inner Saturn System map courtesy NASA

NASA probes and telescopic observations indicate that the Rings consist of billions upon billions of chunks of almost pure water ice. These are thought to range in size from icy dust to the size of a small house. Larger icy moons some dozens of kilometers wide open gaps in the Rings. There’s also evidence of hundreds or thousands of bodies the size of small mountains which aren’t quite big enough to open their own gaps. Water can be turned into oxygen and hydrogen useful for life support, rocket fuel, and numerous industrial processes. There’s not much nitrogen in the Rings to help make fertilizers and provide a more natural breathing mix but another moon, Titan, is not too far away and its atmosphere is rich in nitrogen. Well. Okay. Titan’s not too far away if you have the engines it’ll take to get you to Saturn but we can talk about that later. The ice that makes up the Rings appears to have trace amounts of a set of reddish organic compounds called “tholins” mixed in with it. These would be a source of precious carbon needed for life . . . though less than one percent of the mass of the Rings is likely made up of these materials [1]. You’ll likely need to import metals and other heavier elements from elsewhere even with great recycling . . . but otherwise the inner part of the Saturn system seems a pretty conducive place for humans to live if you can get there.

The space environment contains a great deal of naturally occurring radiation. An unshielded human will get a lethal dose from energetic particles from the Sun and galactic cosmic rays from outside our Solar System pretty quickly. Real World ™ radiation shielding to cope with this problem is heavy and hard to bring with you. Planets with a magnetic field in our Solar System also all have natural radiation belts that can actually make the problem worse. The stronger the magnetic field of the planet and the faster it’s rotating, the more intense the radiation in the belts. Earth’s radiation belts are bad enough. Jupiter’s are borderline apocalyptic. Saturn’s are in between. They’re worse than Earth’s but not quite as bad as Jupiter’s. Yet those same planetary magnetic fields can help by protecting you from some of the solar and galactic radiation once you are nestled down deep inside them. The stronger the planetary magnetic field the better it will shield you once you get below any naturally occurring radiation belts.

The ideal thing would be to find a place which had a nice strong magnetic field but where you were protected from the natural radiation belts that such a magnetic field inevitably creates.

And here’s the beauty of Saturn: its magnetic field is stronger than Earth’s and its radiation belts are worse . . . but they effectively end at the outer edge of the Rings. This is because all the ice there stops the belts from moving down into their orbit. That means that, if you can survive the trip to get there, you have a nice place deep inside a large magnetic field protected from radiation in which to live and raise your kids. And any unwanted visitors have to contend with a long trip to get to you and still have to pass through the radiation belts to get at you. This should promote both life and liberty.

Sure, the first ship you sent would have to have thick and heavy radiation shielding that you wouldn’t actually need once you got down into the Rings. But you could use metals and other heavy elements that were scarce at Saturn for that shielding if you had a powerful enough propulsion system to carry all this stuff in the first place. You could then dismantle much of your shielding once you arrived and recycle it into other stuff you needed.

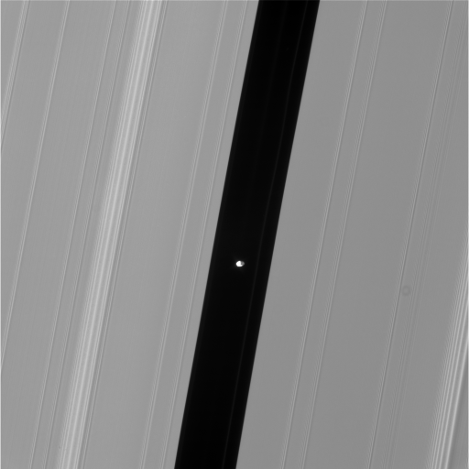

Turns out there’s even a providential gap in Saturn’s outer A-Ring (see “Encke division (Pan)” on Figure 3 above) held open by the relatively small icy moon, Pan, where you could settle in. A photo of Pan with the gap edges seen from “above” is below in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Pan in the Encke Gap. Photo courtesy NASA. https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/images/pia08317-brilliant-pan/

Pan is about 26 km (16 miles) across. The Gap is about 325 km (200 miles) wide. The white material on either side are the Rings themselves . . . made up of billions and billions of chunks of water ice. Turns out living in a big space station parked in the Gap several hundred miles from Pan would have certain advantages. The biggest of which is that Pan’s gravity keeps the Gap free of the tumbling Ring ice boulders that could otherwise damage your spacecraft.

At this point the Rings are looking pretty good. The water ice provides a stable basis for a life support loop. Titan is nearby with nitrogen for fertilizers and makeup atmosphere. You can probably get organics at least in trace quantities from the Rings themselves. You might have to import metals or be lucky to discover one of Saturn’s 274 presently known moons has some.

Mining the Sky . . . Farming it . . . Breathing it . . . Swimming in it . . . and Recycling It . . .

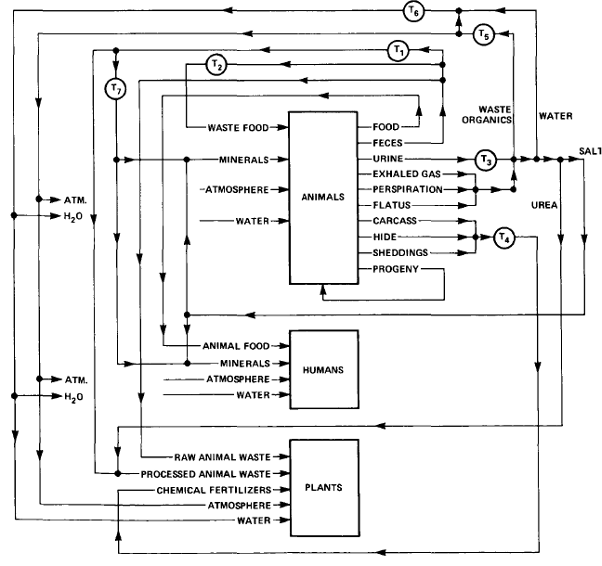

This is all good stuff . . . but it’s like having all the ingredients to make a meal without a kitchen or a recipe. Settling in the Rings would require that you know how to set up a sustainable closed loop ecology that can use all these materials very carefully with as little waste as possible. “Closed loop” in this context means recycling water, organics, and all waste products to the maximum possible extent as shown below in Figure 5.

Figure 5: Example loop-closing flow sheet for generalized closed life-support system after Ref [2] which copied it from Ref [3]. Some of these loops would be closed on a spacecraft by animals and plants and others by machines.

The “loops” of material and energy flows are “closed” because waste or byproducts of the various organisms that live in the system are converted back into resources those organisms can use over and over again with very little loss. The biosphere of the Earth of course does all this quite naturally. All the life that we share our planet with participates in the process in many ways and to varying extents. People have been studying how to better cultivate our garden home for a very long time. This might be understood as the beginnings of the study of the web of relationships between organisms and their environment that we call “ecology” today.

The Earth however has the advantage of enormous mass and volume plus significant quantities of time in which to perform all of this recycling. The specific problem of trying to do what Earth does naturally in miniature aboard a spacecraft has been studied since the dawn of the Space Age. We have made machines that can do in a very small space a few of the things that Earth does via organisms and environment. The first spacecraft couldn’t recycle anything though. The astronauts carried all their oxygen, water, and other necessities plus equipment to keep the atmosphere in their spacecraft comfortable. These early environmental control and life support systems (ECLSS) are simple and reliable but don’t work for very long missions because you have to carry too much stuff with you. So we started closing loops. You might hear this called “regenerative” life support systems. That means that the system can recycle some or all of its resources. The International Space Station (ISS), for instance, has the most advanced environmental control and life support system built to date. Its water recovery system has recently demonstrated recovery of 98% of the water in the U.S. segment of the Station on orbit. That means that, if you bring 100 pounds of water aboard, the system is able to keep 98 pounds of it in continuous circulation. So we are well and truly on our way to closing the water loop though this comes with lots of jokes about turning yesterday’s coffee into today’s coffee on the ISS. This is funny . . . but it isn’t like it’s any different than the history of the water we drink every day on Earth. It’s just Earth has more steps in the process and takes more time to recycle the water.

One of the things that I am excited about in Ringer is showing how humans aren’t the only Earth life we’re likely to bring with us to space. Note the animals and plants in Figure 5. The best way we know to live comfortably in space, as on Earth, will involve bringing other Earth life with us. Plants remove carbon dioxide, help oxygenate the air, and can make good use of many of the waste products of their more mobile human and animal shipmates. NASA and other space agencies have been studying natural ecologies and tried to replicate some of what we’ve learned in simplified childlike miniatures on the Space Shuttle, ISS, and other places. Figure 6 below is a nice photo taken aboard the ISS showing a zinnia that an astronaut posed for the camera in the station’s Cupola module.

Figure 6: Zinnia shown in the ISS Cupola. Photo courtesy NASA Johnson Space Center’s Flickr account. The plant was grown in a grey rooting “pillow” containing nutrient rich growth media. https://www.flickr.com/photos/nasa2explore/24460739396/

Russian, American, and Chinese researchers (among others) have experimented with building small enclosed ecologies on Earth. The Russian BIOS series of experiments, the American Biosphere 2, and the Chinese Lunar Palace have all led to dramatic crop yields, lessons for sustainable terrestrial agriculture, and made important progress on the road to a closed ecological life support system. For instance the Chinese Lunar Palace 365 experiment reported in 2018 the successful complete recycling of oxygen, water, and vegetarian food for a crew of four people in a 500 square meter ground based lab at Beihang University in Beijing for over a year. No currently orbiting spacecraft has enough room to try this but the International Space Station has already tested out some pieces of it with two different plant growth chambers studying the effects of microgravity on farming in space and also providing the crew with some fresh produce occasionally. For the curious; to the best of my knowledge, the first vegetable grown, harvested, and eaten is space was “"Outredgeous”" red romaine lettuce.

These efforts are just the beginning of learning to live in space and have all occurred within only a few hundred miles of the surface of our home world. Everyone acknowledges that we’ve got a lot to learn before we’re ready to bring our own little pieces of home to space with us. I would be lying if I said that we were close to being able to do this on the scale that we show in the book. It will take many decades of consistent investment in technology experiments for us to learn how to replicate in space the functions that our home planet performs for us entirely naturally. Advances will need to be made in enclosed farming, ecology, recycling even residual waste, and much more. Part of what the many commercial space stations mentioned in Dabare were doing was making those advances for use both on Earth and in making missions farther from Earth possible for anyone other than a robot.

We’ll need to learn to be even more efficient with recycling as we go farther out but our experiments have already taught us quite a bit about recycling our water and growing plants in the space environment, which are big steps. One rather unsurprising thing has become clear though: Earth life really doesn’t enjoy microgravity or radiation. All this gardening sure would be easier if we could have as close to an Earthlike environment as possible.

So, let’s do something about that shall we?

Go Big . . . Or Don’t Go

Radiation and microgravity are central problems Earth life has faced to date on space missions. There are many potential solutions to these problems like genetic engineering, cocktails of designer drugs, and sleeping in small centrifuges (I’m not kidding). You’ve probably seen all of these (except maybe that last one) in a variety of science fiction books or shows. One or more of these solutions might also appear in future novels in this series but for Ringer we wanted to show Mark One Mod Zero bog-standard boring old humans (and baobab trees and cats and chameleons . . . ) thriving in space.

It turns out that one really obvious solution to the problem of living in the microgravity of space is to spin the part of the spacecraft where they live to simulate gravity. Most people can tolerate this indefinitely if the whole thing is big enough and rotates no more than a couple of rotations per minute [Ref 4. pg. 48]. Doing the math on this means a big rotating torus, sphere, or cylinder. For the record this will require a very large spacecraft by today’s standards. Say, if you want to give your crew one gravity at one rotation per minute that would give you a bird almost 900 meters (3000 feet) across. The biggest spacecraft ever built, the ISS, is 109 meters (358 feet) long at its widest point and it’s not strong enough to spin at that speed. We’re nowhere near being able to build what I’m talking about here. But it turns out that if you could build a spacecraft that big then carrying the extra shielding that you need to reduce local radiation levels inside the spinning habitat to tolerable levels for Earth life is . . . well . . . not easy exactly. But not the hardest thing on your to-do list if you’re going to build a thing that big anyway.

I call this design approach “Go Big Or Don’t Go” and it’s the one sure-fire way that I know to make an environment that terrestrial life could survive in anywhere you could put such a spacecraft.

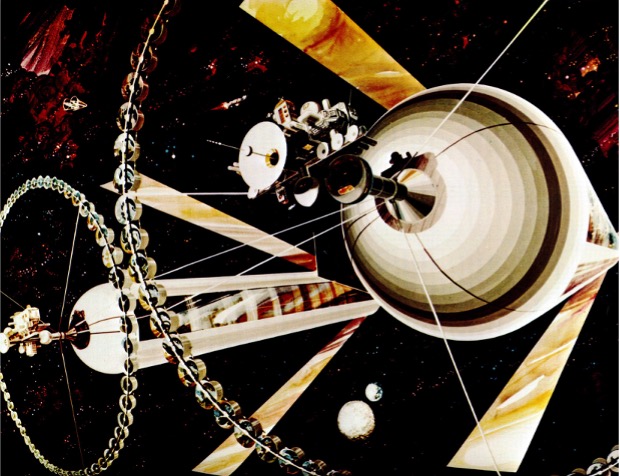

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky first wrote about the idea of spinning a vehicle to create artificial gravity in a manuscript entitled “Free Space” as early as 1883 [Ref 4. pg. 60]. However, it took almost a century, a Stanford professor named Gerard K. O’Neill, and a team of professionals and students during a 1975 summer study to put some engineering rigor into imagining it at the scale I’m talking about for Ringer. That study [Ref. 5] and Dr. O’Neill’s later 1976 book, The High Frontier, brought the idea of free-flying space settlements to a popular consciousness troubled by energy shortages, pollution issues, and other concerns about the future. It was popularized on screen in 2001: A Space Odyssey, Gundam, and Babylon 5 among many other places. This is why they’re called “O’Neill Cylinders” in Figure 7 below.

Figure 7: Artist’s painting of “Island Three” type O’Neill cylinders from pg. 144 of Ref. 5. Twin paired 32 kilometer (20 mile) long cylinders. Note they’re paired and rotating in opposite directions to make them easier to control.

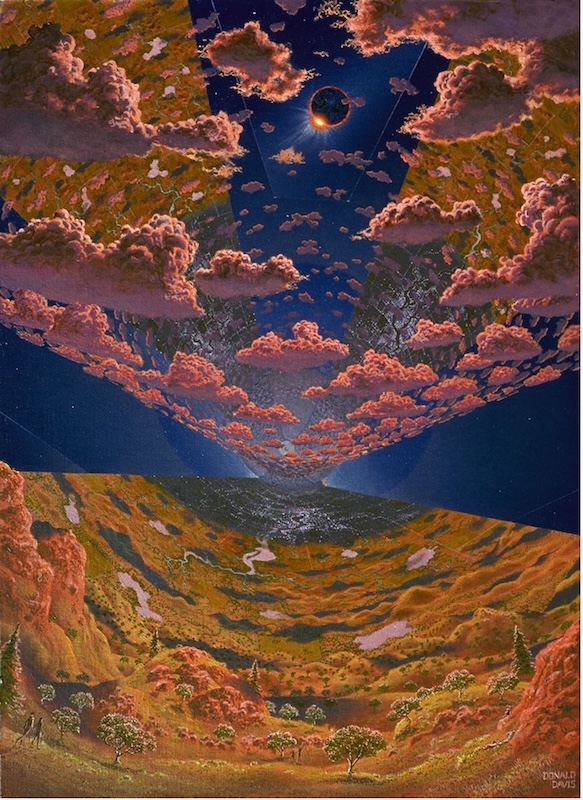

The insides of the original O’Neill cylinders were fascinating places to imagine. Each used three large mirrors to reflect sunlight into giant windows made of lunar glass. Thus natural light could be used to grow plants (See Figure 8 below).

Figure 8: Artist’s impression of what the inside of such a cylinder might look like courtesy NASA and Don Davis.

This was all amazing theoretical engineering work backed with realistic calculations and the sheer scale of it captured an enduring chunk of the popular imagination. However, building a twenty-mile-long space habitat wasn’t a particularly practical place to start. Ref [5] lays out a whole national strategy and even an economic justification for doing it. Nothing in it seems to violate the laws of physics and elements of that strategy, like all that closed loop life support stuff above, have actually been worked on consistently by NASA (among others) ever since. The vision of The High Frontier required lunar bases, extensive cis-lunar transportation infrastructure, use of lunar resources, the ability to manufacture large space structures, and an economic demand for space based solar power satellites beaming a significant fraction of Earth’s energy down to the surface. There’s no reason in principle you couldn’t do it but no one was sure how you’d ever pay for it.

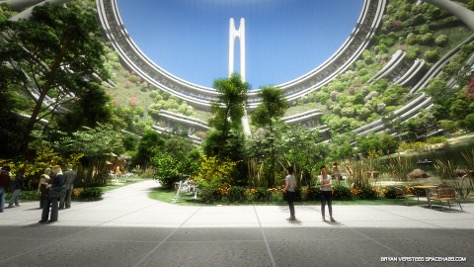

People soon started looking for smaller ways to start. That meant looking for smaller space station designs to start with. Enter Kalpana One (See Figure 9).

Figure 9: Kalpana One exterior panorama courtesy of Bryan Versteeg at https://spacehabs.com/. Used with permission.

Named in honor Dr. Kalpana Chawla (one of the astronauts lost in the destruction of Space Shuttle Columbia), its size, shape, and other parameters are described in Ref [6]. It’s a shortened single cylinder that is very much smaller than the O’Neill Island Three designs above. Kalpana One’s habitat was designed for 3,000 people, rotated twice a minute, and was 500 meters (1640 feet) across. It took in sunlight in complex arrays at its endcaps and was powered by both solar panels and power beamed to it by another nearby solar power satellite. Everyone had a quite a bit of living space (170 m2 per person or 1830 square feet). The station was not designed to be the ideal space city of the future but rather the first space village. The interior visualizations are pretty wild (again thanks to Bryan Versteeg).

Figure 10: Kalpana One artist’s rendering looking along the direction of spin. Courtesy of Bryan Versteeg at https://spacehabs.com/. Used with permission.

Figure 11: Kalpana One artist’s rendering looking along the axis of the station. Courtesy of Bryan Versteeg at https://spacehabs.com/. Used with permission.

Note that the images above don’t show any farm space. That’s because it’s under the floor or in the central core in space-going equivalents of modern vertical farming intensive cultivation techniques.

Figure 12: Combined aquaculture and hydroponics farm. Controlled lighting and crop cycles tailored to the plants’ specific needs can make for ridiculously high crop yields. Courtesy of Bryan Versteeg at https://spacehabs.com/. Used with permission.

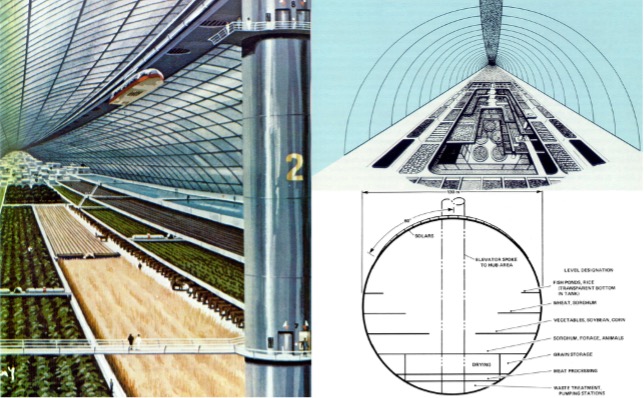

This type of farming has been the focus of serious research for a while and there are several businesses built around the technique. This is by no means a common way to grow food and it is still in its infancy but there’s plenty of evidence that people can grow food like this. They can in fact grow quite a lot of it. A way to combine these techniques might be cascading vertical farming levels buried in the floors of the station’s hull and surrounded by fish ponds whose wastes (carefully filtered) flow down through rice paddies to help irrigate the growing levels below them as shown below in Figure 13.

Figure 13: Collage of “cascading farms” imagery from Ref 6. Left (Ref 5. Ch 3 frontispiece) shows a painting of how vertical farming might look in a torus-shaped colony. Right-upper (Ref. 5 Fig 5-11) -another view. Right-lower (Ref.6 Fig. 5-12) cutaway view.

I don’t think the cows in the above picture will stay lined up neatly in rows for very long and I’d like any farm animals on the station to have a bit more humane environment but otherwise this (combined with sub-floor agricultural sections illustrated in Fig. 12) looks like it could provide lots of food for lots of people in a relatively efficient and ethical manner.

It will however take energy. Quite a lot of energy. This means Chawla’s power plant is perhaps the key technology that makes the whole setting work.

Some straightforward calculations show that just growing the food for the three thousand people on a space station like the one we depict in the story would take from three to forty megawatts of electrical energy. Space settlements built near Earth enjoy the benefits of abundant solar power but the amount of energy a solar panel can make falls off very quickly as one goes farther out. Assuming the maximum theoretical efficiency from a recent NASA study (Ref [7]) a forty- megawatt solar array in Earth orbit would be a square about 206 meters (676 feet) on a side. At Saturn’s distance from the Sun you’d need a solar array over two kilometers (about 1.3 miles) on a side to get the same forty megawatts. We might be able to power small probes with sunlight out at Saturn but the civilization we are talking about in this novel will take a lot more power.

The figures above are just for growing food. We would have to add in all of the power you would need for air handling, water management, atmosphere processing, keeping millions of tons of habitat spinning, and making sure the whole mess stayed in orbit. By the time we’re done with adding all that up Chawla could easily end up using gigawatts of electrical power. Some kind of nuclear power is a good answer for making lots of power in a small package where it’s dark or dim and it has been used in space since nearly the beginning of the Space Age. Russia, the United States, and China have already flown power sources that make a few hundred watts from the heat of a decaying radioactive material (usually plutonium). Russia and the United States both flew small uranium fueled nuclear fission reactors decades ago in principle like the nuclear reactors in use for naval vessels and commercial power around the globe today. The last decade has seen a resurgence in interest in space nuclear fission technology and indeed that’s the area where most of my actual day job work is done. For an introduction to space fission power see Ref [8]. But even uranium fission reactors cannot provide as much power as Chawla’s likely to need.

Don’t worry though. We won’t need a long extension cord. We’ll just have to bring a little star of our own along for the ride.

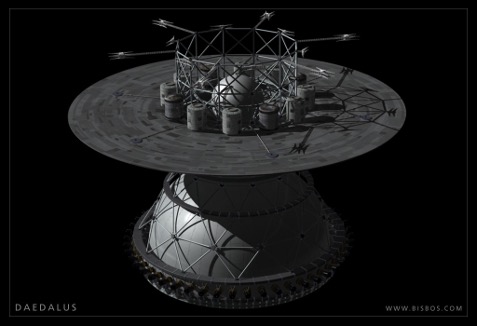

Nuclear fusion looks to provide a solution. A small team of researchers did a five year technical study on how to get a robotic space probe to another star system around the same time that Gerard O’Neil was pondering building massive space colonies to solve terrestrial problems. It was called Project Daedalus and remains, to my knowledge, the most detailed professional engineering conceptual design of what a real starship might look like to date. What they ended up with was a design for a two stage 100,000+ ton nuclear fusion pulse rocket that got a 500-ton robotic probe to Barnard’s Star in less than a human lifetime as described in Ref [9]. Most of the mass was fuel. It was . . . not small:

Figure 14: Daedalus probe next to the Empire State Building for scale. Courtesy Adrian Mann at http://www.bisbos.com/space_n_daedalus_gallery.html. Used with permission.

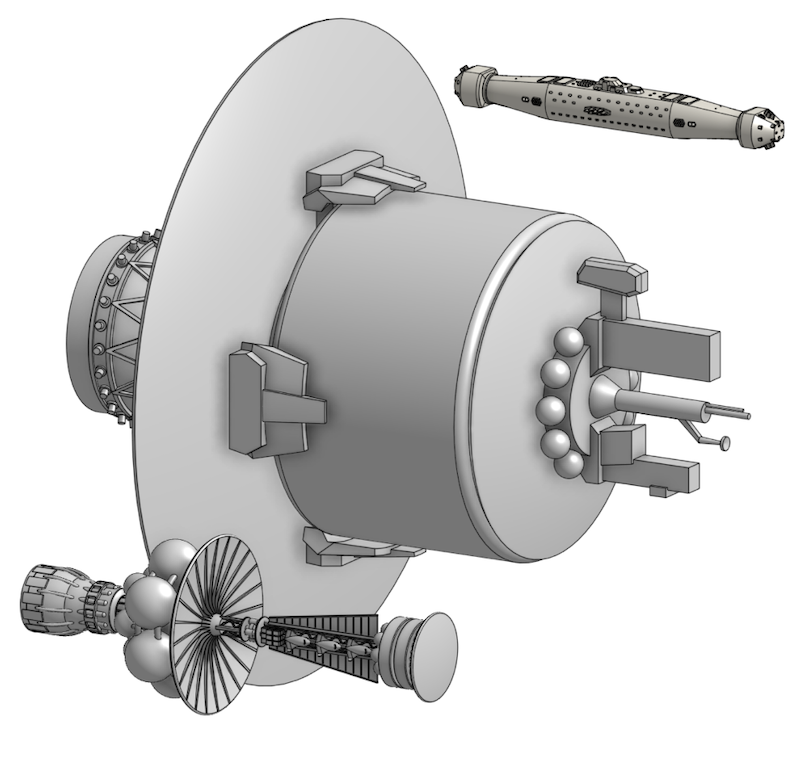

That giant bell at the bottom is a 100 meter (328 feet) wide fusion rocket engine. The coil at the very bottom “borrows” some of the fusion plasma’s energy and turns it into electrical power to keep it running. Lots and lots of electrical power at millions of volts. A better view of that engine without all of the spherical fuel tanks appears in Figure 15 below.

Figure 15: Daedalus first stage with the fuel tanks removed making the fusion rocket "bell" clearer. Courtesy Adrian Mann at http://www.bisbos.com/space_n_daedalus_gallery.html. Used with permission.

You can see the many cylindrical fusion initiators at the bottom which were supposed to project beams of electrons against little pellets of fusion fuel 250 times a second to detonate them. A giant molybdenum end bell that works with magnetic field coils to direct the fusion plasma away from the spacecraft is inside the triangular grid truss work. The circular disk at the top helps shield the rest of the spacecraft from the heat radiating off the bell at 1600 K (2912 F). A great deal of “plumbing” does not appear on this diagram and would have to be worked out in a real spacecraft but the nearly 200 page final report is very thorough.

The conceptual work on Daedalus was finished in 1978. The authors clearly stated that much of their work was highly speculative and it remains so today. The key point for our purposes is that we still do not have fusion reactors that can make reliable electrical energy today . . . let alone fusion pulse rockets big enough to play a really weird game of football in. There are many, many issues with making this probe a reality. Potentially the biggest one is how to detonate tiny pellets of liquid helium-3 and deuterium. Helium-3 is rare isotope of helium that makes a great nuclear fusion rocket fuel . . . if we can figure out how to get enough of it and cause it to fusion.

Here’s where our worldbuilding for Ringer gets a little more speculative and we ask “what if we got this working and put one on the back of a Kalapana cylinder?” I love putting meat on the bones of this kind of speculation, grounded in the engineering extrapolations, and backed by decades of serious research. The answer is Chawla Station; which might look something like Figure 16 below:

Figure 16: RSC Chawla with a few other unnamed Baen friends. Tum-te-tum-tum. Image courtesy Tom Pope. Used with permission.

The central cylinder is the 500 m (1640 foot) wide habitat and spins to create artificial gravity on its interior surface. It rests in the middle of two non-rotating pieces. At the back you can see the end bell of a fusion pulse rocket very similar to Daedalus’ . . . but four times larger. That rocket is what got Chawla to Saturn in the first place and can be run in a low power mode where it “only” provides the electrical energy needed to keep the lights on and keep the station in orbit. The array of spheres and struts at the front is a zero-gee docking and industrial zone. The massive disk in the middle is a thermal shield and radiator system that deals with the waste heat from the spacecraft which has no way of escaping except radiating to space. Chawla is enormous and way bigger than anything we could realistically build today. It is not, however, bigger than something we could imagine building with physically realizable materials. We figure a society that could make a space elevator could figure out how to make Chawla.

There are many more details of each of these ideas that underpin why things work in the setting but these will have to be kept for later stories and articles. I hope you’ve enjoyed this peek under the hood at the science and engineering of Ringer. I also hope that the result of our work provides you with a glimpse into a better future we can all help make for our descendants.

References:

[1] Jeffrey N. Cuzzi, Richard G. French, Amanda R. Hendrix, Daniel M. Olson, Ted Roush, Sanaz Vahidinia, HST-STIS spectra and the redness of Saturn’s rings, Icarus, Volume 309, 2018, Pages 363-388, ISSN 0019-1035, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2018.02.025

[2] Billingham, J., Gilbreath, W., & O’Leary, B. (Eds.). (1979). Space resources and space settlements (NASA SP‑428). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19790024054/downloads/19790024054.pdf

[3] Spurlock, J. M., Review of Technology Developments Relevant to Closed Ecological Systems for Manned Space Missions. Final Report, NASA Contract No. NASw-2981, CR-153000, SAE, New York, 1977.

[4] Clément, G., & Bukley, A. (2007). Artificial gravity (Space Technology Library, No. 20). Springer. https://www.amazon.com/dp/B00177T5TM

[5] Johnson, R. D., & Holbrow, C. (Eds.). (1977). Space Settlements: A Design Study (NASA SP‑413; LC‑76‑600068). NASA Ames Research Center. Space Settlements: A Design Study - NASA Technical Reports Server (NTRS)

[6] Globus, A., Arora, N., Bajoria, A., & Straut, J. (2007). The Kalpana One orbital space settlement: Revised. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. https://space.nss.org/kalpana-one-space-settlement/

[7] Rodgers, E., Gertsen, E., Sotudeh, J., Mullins, C., Hernandez, A., Le, H. N., Smith, P., & Joseph, N. (2024, January 11). Space-based solar power (Report ID 20230018600). Office of Technology, Policy, and Strategy, National Aeronautics and Space Administration. https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/otps-sbsp-report-final-tagged-approved-1-8-24-tagged-v2.pdf?emrc=744da1

[8] Presby, A. (2017). Nuclear fission power in space. Baen. https://www.baen.com/nuclearfission

[9] Project Daedalus Study Group. (1978). Project Daedalus: the final report on the BIS starship study. London :Space Educational Aids Ltd. for the British Interplanetary Society Ltd.

For Further Learning:

Spacehabs.com – Visualizing The Future – Bryan Versteeg is responsible for the beautiful images of Kalpana One shown earlier. You can find these and many more on his website.

Bisbos.com: Daedalus – By far the most detailed artistic renderings of the Daedalus probe presently available by the excellent Adiran Mann.

Reference 4 above4 - This is by far the single best book I’ve found on the problems of microgravity, how to generate “artificial gravity,” the limits of that technology, and some ways around them. A bit dated but still a great resource. Also . . . sleeping on a turntable.

Technical Projects - The British Interplanetary Society – Material on the original Project Daedalus and the several starship technical studies that the British Interplanetary Society has done since can be found here. Sadly the detailed Daedalus studies are hard to come by digitally but can still be found in some university libraries.

“Origins of the West African Launcher from TCG Files” by Andy Presby - Baen Books – An in-universe article about the maglev assisted single stage to orbit cargo launch system that serves as a central plot point in The Dabare Space Launcher.

Copyright © 2025 by Andy Presby

Andy Presby is a former U.S. Navy nuclear submarine officer and current project manager working space nuclear power and propulsion systems in the aerospace sector. He has degrees in spacecraft systems engineering, astronautics, and physics. This non-fiction article describes the world of Joelle Presby’s Ringer. Joelle is a former U.S. Navy nuclear surface ship engineering officer and former business consultant. Andy and Joelle also have the pleasure of being married to one another. Dinner conversations can get interesting and rapidly confuse their three rather young children.