From Imperial Stars: Volume 1

From Imperial Stars: Volume 1

Copyright 1986 by Jerry Pournelle

ISBN: 0671-65603-1

One reason Jim Baen keeps me around is that he likes to talk. We have endless telephone discussions of column topics, and they tend to spill over to anything else going on. In the course of one conversation we got to the subject of the Ayatollah Kockamamie, and Jim said something about "all ends of the political spectrum ...er, points."

"Curious you should put it that way," I replied. "I wrote my dissertation in political science on a proof that the political spectrum has more than one dimension; that the old left-right category doesn't really work."

"Now there's a column," Jim said. And on reflection I agree. At least it makes a good appendix to my tirade on what's 'wrong with the social sciences.

The notion of a "left" and a "right" has been with us a long time. It originated in the seating arrangement of the French National Assembly during their revolution. The delegates marched into the Hall of Machines by traditional precedence, with the aristocrats and clergy entering first, then the wealthier bourgeois, and so on, with the aristocracy seated on the Speaker's right. Since the desire for radical change was pretty well inversely proportionate to wealth, there really was, for a short time, a legitimate political spectrum running from right to left, and the concept of left and right made sense.

Within a year it was invalidated by events. New alliances were formed. Those who wanted no revolutionary changes at all were expelled (or executed). There came a new alignment called "The Mountain" (from their habit of sitting together in the higher tiers of seats). Even for 18th Century France the "left-right" model ceased to have any theoretical validity.

Yet it is with us yet; and it produces political absurdities. No one can possibly define what variable underlies the "left-right" continuum today. Is it "satisfaction with existing affairs?" Then why are reactionaries, who most definitely want fundamental changes in the system, called "right wing"? Worse, the left-right model puts Fascism and Communism at opposite end-- yet those two have many similarities. Both reject personal freedom. Some would say they are more similar than different.

What are we to make of Objectivists and the radical libertarians? They've been called "right wing anarchists," which is plain silly, a total contradiction in terms.

Nor is this all academic trivia. "There is no enemy to the Left" is a slogan taken very seriously by many intellectuals. "Popular Front' movements uniting "the Left" (generally socialists and communists) have changed the destinies of nations. Conservatives swallow hard and treat kindly other members of "the Bight" even when the others seem despicable by Conservative standards. The left-right model, although nonsensical by any theoretical analysis, has had very real political consequences.

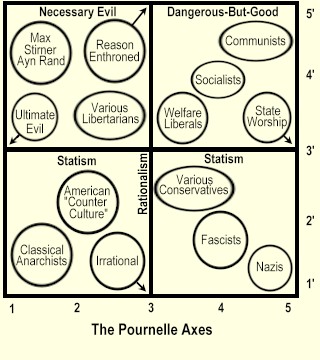

Some years ago I set out to replace the old model with one that made more sense. I studied a number of political philosophies and tried to see what underlying concepts separated them from their political enemies. Eventually I came up with two variables. I didn't then and don't now suggest these two are all there is to political theory. I'm certain there are other important ones. But my two have this property: they map every major political philosophy and movement onto one unique place.

The two I chose are "Attitude toward the State," and "Attitude toward planned social progress".

The first is easy to understand: what think you of government? Is it an object of idolatry, a positive good, necessary evil, or unmitigated evil? Obviously that forms a spectrum, with various anarchists at the left end and reactionary monarchists at the right. The American political parties tend to fall toward the middle.

Note also that both Communists and Fascists are out at the right-hand end of the line; while American Conservatism and US Welfare Liberalism are in about the same place, somewhere to the right of center, definitely "statists." (One should not let modern anti-bureaucratic rhetoric fool you into thinking the US Conservative has really become anti-statist; he may want to dismantle a good part of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, but he would strengthen the police and army.) The ideological libertarian is of course left of center, some all the way over to the left with the anarchists.

That variable works; but it doesn't pull all the political theories each into a unique place. They overlap. Which means we need another variable.

"Attitude toward planned social progress" can be translated "rationalism"; it is the belief that society has "problems," and these can be "solved"; we can take arms against a sea of troubles.

Once again we can order the major political philosophies. Fascism is irrationalist; it says so in its theoretical treatises. It appeals to "the greatness of the nation" or to the volk, and also to the fuhrer-prinzip, i.e., hero worship.

Call that end (irrationalism) the "bottom" of the spectrum and place the continuum at right angles to the previous "statism" variable. Call the "top" the attitude that all social problems have findable solutions. Obviously Communism belongs there. Not far below it you find a number of American Welfare Liberals: the sort of people who say that crime is caused by poverty, and thus when we end poverty we'll end crime. Now note that the top end of the scale, extreme rationalism, may not mark a very rational position: "knowing" that all human problems can be "solved" by rational actions is an act of faith akin to the anarchist's belief that if we can just chop away the government, man truly free will no longer have problems. Obviously I think both top and bottom positions are whacky; but then one mark of Conservatism has always been distrust of highly rationalist schemes. Burke advocated that we draw "from the general bank of the ages, because he suspected that any particular person or generation has a rather small stock of reason; thus where the radical argues "we don't understand the purpose of this social custom; let's dismantle it," the conservative says "since we don't understand it, we'd better leave it alone."

Anyway, those are my two axes; and using them does tend to explain some political anomalies. For example: why are there two kinds of "liberal" who hate each other? But the answer is simple enough. Both are pretty thorough-going rationalists, but whereas the XIXth Century Liberal had a profound distrust of the State, the modern variety wants to use the State to Do Good for all mankind. Carry both rationalism and statism out a bit further (go northeast on our diagram) and you get to socialism, which, carried to its extreme, becomes communism. Similarly, the Conservative position leads through various shades of reaction to irrational statism, i.e., one of the varieties of fascism.

On the anti-statist end of the scale we can see the same tendency: extreme anti-rationalism ends with the Bakunin type of anarchist, who blows things up and destroys for the sake of destruction; the utterly rationalist anti-statist, on the other hand, persuades himself that somehow there are natural rights which everyone ought to recognize, and if only the state would get out of the way we'd all live in harmony; the sort of person who thinks the police no better than a band of brigands, but doesn't think that in the absence of the police, brigands would be smart enough to band together.

The whole thing looks like Figure One.

Now I do not claim this is the model of modern politics; I do claim that it is a far better model than the one we're using, and in fact I go farther and claim that the "left-right" model so ubiquitous amongst us is harmful. And while I understand that some ideologues find the "left-right" model useful to their cause, and thus have a powerful incentive to gloss over its failures, what puzzles me is why so-called objective political "scientists" don't try to abolish it, at least in freshman political science classes.

But then I've already admitted I don't understand the "social sciences" to begin with, and I needn't say all that again.

Never before have I felt called upon to add to one of the redoubtable Dr. Pournelle's

columns, but Jerry has been guilty of that most heinous of auctorial sins: modesty.

Seriously, Jerry seems to have come up with a useful, predictive, scientific

measuring device for the social so called sciences, and passed it off as an

"Appendix," forsooth! In politics alone the results of the widespread use of the

Pournelle Axes would be revolutionary: pols would be required not only to declare

themselves but to reveal precisely and literally their political position- and live with

it. For example Teddy Kennedy from his own pronouncements cannot be less than a

4.5/4.5'-how many people in this country would vote for a 4.5/4.5' once it was revealed

for what it was? Give me a 2/4' any day! (That's what I am; once you have analyzed

your own position, you may find your own political choices becoming remarkably simplified.

Reagan and Crane, both at 4/2', make me a little nervous. Bush, at 3/3', looks pretty

good.)

Note also the odd sympathy and support between the diagonally facing quadrants, as opposed

to the antipathy between contiguous ones-at first blush diagonals would seem to make

natural enemies, yet artists, intuitive by definition and anti-statist almost by

definition, yearn for a world where true art is replaced by Socialist Realism-while libertarians

provide the theoretical groundwork for right-wing dictatorships! Odd, very odd.

Note also how one can define "reasonable" as any position no farther from 3/3'

than one's own: those farther out in one's own quadrant are pleasantly dotty; those

farther out in another, unpleasantly so . . .

But it's not my aim to analyze the Pournelle Axes in depth-- any such attempt by me would

be necessarily superficial. One of these days I'll get another column from him on this

subject. My point is that for this column Jerry Pournelle is guilty. Guilty as sin.

Of modesty.

-Jim Baen