The Grammarian

A Joe’s World Story by Eric Flint

From what is short but already bitter experience I have come to recognize which Callings—yes, that’s what they call the damn things—will be the most pernicious. What do I mean by pernicious? Start with “perilous beyond all reason,” continue with “wounds guaranteed,” and finish with “pays worse than you can imagine.”

The tip-off is the messenger who delivers the Calling. The more gaunt, emaciated, bedraggled, and with the greatest expression of despair leavened with the tiniest, itsy-bitsy spark of hope in their visage… the worse it’s going to be.

Alas, the waif who showed up at our door just after dawn on a dreary autumn day in New Sfinctr made my blood turn to ice in less than a second. Oh, no—

Jenny and Angela pushed me aside and shepherded the girl—I think she was a girl; hard to tell when their misery is measured in orders of magnitude—into the foyer.

“You poor dear!” exclaimed Angela. “Would you like some hot tea?”

Without waiting for an answer, Jenny hurried toward the kitchen. “I’ll get the kettle going.”

“Here, sit on this couch,” said Angela. “It’s the most comfortable one we have.”

Indeed, it was—which was why I’d just sprawled onto it not three seconds before the knock came on the door. So much for my nap after being awakened too early… Well, not exactly that, as frisky as Jenny and Angela’s mood had been that morning. But I was tired, I surely was.

By now, there’d been enough commotion to draw the attention of the dwelling’s other inhabitants. Greyboar came lumbering down the stairs, yawning and rubbing his face with a hand roughly the size of a dinner plate, except for being a lot thicker. The now-Hero, Excelsior had in his earlier (and way, way, way more lucrative) life been the world’s champion professional strangler.

Did he look like it? Does a tiger shark look like an apex predator?

Lucky for them, tiger sharks aren’t encumbered by idiot social conventions the way humans are. Greyboar and I had been forced to give up our former contented life as a chokester and his manager and become a Hero and Sidekick. Hero, thanks to his maniac sister’s romantic entanglement with a lunatic artist. Rescuing the sod had required us to penetrate to the very depths of the underworld, which we couldn’t do without swearing to give up our wicked ways and devote the rest of our miserable lives to righting wrongs and rescuing maidens and other such foolishness.

Speaking of maniac romantic entanglements, Greyboar’s own made her appearance right then. First, at the stop of the stairs looking down in her indescribably weird way of examining reality; then—don’t ask me how she did it; nobody can figure it out—she was standing on the floor of the foyer making her own way through the sitting room to the kitchen.

“I want mint, ginger, and chamomile!” she called out. “It’s good for pregnant women.”

With any other woman, you’d assume that meant she was pregnant herself. But with Schrödinger’s Cat…

Maybe. Pretty much everything about her is maybe. She might just have decided that if she drank herbal tea made of mint, ginger, and chamomile that it would help some other woman who was actually pregnant.

The scariest thing about that is that it just might be true. I’m convinced the Cat does not live on the same plane of existence the rest of us do.

A loud creaking and groaning from heavily stressed wood and fabric accompanied Greyboar sitting down on his favorite armchair. “Do I take it we have a customer?” he asked.

“Don’t call them that!” I barked, perhaps a bit shrilly. “The term ‘customer’ refers to someone who pays for something.” I scowled at the girl hunched on the couch next to Angela, being comforted. “Does that urchin look like she has two pennies to rub together? Ha!”

Angela bestowed a scowl upon me. “Greyboar, remind me why Jenny and I are in love with this pitiful excuse for a person.”

The Hero, Excelsior let that question slide. It was clearly rhetorical, anyway. The reasons my two ladies adored me were multitudinous if perhaps a bit indistinct.

“I’m just expressing a reasonable complaint at the gross injustice of our position in life,” I said. “If it weren’t for the money you and Jenny bring in from your seamstress business, we’d all have starved to death by now.”

Jenny and the Cat came back into the living room, bearing cups for everyone. I accepted mine in silence. At that time of day, I’d have preferred ale, but that was true pretty much any time of day. Given the grim reality that was about to be unfolded before us, drinking a concoction of herbs I wouldn’t normally touch might brace me a little.

* * *

As usual, it took the messenger—who was the plaintiff also, of course—quite a while to tell her tale. First, because she was maybe ten years old and not experienced in swift and succinct explication. Second, because Jenny and Angela kept interrupting her with exclamations along the lines of you poor thing! and how horrible that must have been for you! And third, because the tale itself was murky and full of inexplicable menace.

Naturally. “Inexplicable menace” is present in at least three-fourths of the Callings that Greyboar and I get saddled with.

The gist of the tale was as follows: An inexplicable and unseen menace—well, it might have been seen by its victims but none had lived to describe the thing, being, or phenomenon—was ravaging a town somewhere out there, where no sophisticates like ourselves would waste our time exploring the non-wonders of rural bumpkinhood.

Naturally. The Callings that a Hero, Excelsior and his sidekick get afflicted with are never to be found in urban palaces where the work might be lightened by fine pastries and liquors. No, no, no. Those are the sort of venues Greyboar and I used to work in quite regularly in our former life as a professional gripster and his manager. Nowadays, our working environs start with muddy streets covered with animal manure and go downhill from there.

The nature of the ravaging was unclear. The corpses the Inexplicable Menace left in its wake bore no physical wounds or injuries. The cause of death was mysterious. What the deceased all had in common was a gaunt and emaciated physique coupled with an expression of utter and disconsolate despair on their faces.

The remains could be found anywhere but seemed to be concentrated in and around the town’s cathedral.

Naturally. Leave it to the Old Geister to draw toward Him whatever Inexplicable Menaces might be lurking about. Why not? Being the Supreme Creator, He’s the biggest inexplicable menace there is.

So, there it was. Our Calling. Sally forth to… whatever the town’s name was, I can’t remember. (Hutburg? Dumpville? Whatever.) Uncover and identify the inexplicable menace. Make it easily explicable because we make it deceased, defunct, demolished, or, at the very least, disappeared.

“Doesn’t seem like too much of a challenge,” opined Greyboar, cracking his knuckles.

I hate it when he does that. Our budget’s stressed badly enough as it is, without adding the cost of home repairs due to excessive vibrations.

* * *

We set out the next day. Transportation wasn’t a problem. That was one of the few bright spots in our new, impoverished condition. We still owned the huge coach we’d purchased before we were brought down by penury, that we’d used to smuggle Hrundig and the Frissault women out of New Sfinctr a while back. (Don’t ask. You really want to hear the tale of how an Alsask barbarian and his upper-class lady and her children got into trouble—never mind. It’s too ridiculous to be believed.)

Anyway, we still had the coach and Oscar and his boys were still willing to serve as our teamsters. Without pay, mind you. Oscar said the notoriety—no, Lord help us, they call it “fame” now that Greyboar’s an official Hero—brings them more than enough business to make the occasional freebie jaunt worth it to them.

One of the few other benefits of our new status was that the guards at the gates never hassled us any longer. (Not that they’d hassled us much in the old days. Greyboar demonstrating his thumbspread had usually been enough by itself to quell incipient officiousness.)

So, off we went, down one of the roads leading almost due east of New Sfinctr. That was mostly farm country out there—so I heard, anyway—until you reached the southern stretch of Joe’s Mountains. According to the waif, her town was nestled in the foothills of the mountains. It’d take us at least a day and a half to get there.

Oh, and it turned out the town’s name was Sylvan Springs.

Once we got clear of New Sfinctr’s none too salubrious outskirts and reached the countryside proper, Angela and Jenny started ooh-ing and ah-ing over the landscape. But even their indefatigable enthusiasm for all things ran dry soon enough. Acre after acre, mile after mile, of cropland. I believe most of it was wheat. I’m not sure. My skills at discerning different grains start with flour, and don’t improve much thereafter. Refined flour, whole wheat flour—I believe cake has its own type as well—and then you get into the really obscure stuff like semolina and durum. There’s even something called couscous, but I don’t know what it is because I’ve never asked. I’m afraid I might have eaten it at one time or another. If I did, I don’t want to know.

Eventually, toward sundown of our first day of travel, the waif emerged from her semi-comatose state and started talking a bit. Her name was Patty, she was nine and a half years old, and… she ran dry about then. Angela and Jenny tried to get her to talk about her family but that just made the girl shrivel up again.

We spent the night at a rural roadside inn. The less said about it the better. At least the bedbugs were within my weight range.

We reached the town of Sylvan Springs early in the afternoon. I’m not sure what a sylvan is, but I don’t think I spotted any. And for sure and certain there were no springs.

We didn’t spend much time examining the surroundings, though. At the edge of town, we disembarked from the coach. Oscar and Patty remained there while the rest of us proceeded into the town itself.

Soon, a great sense of foreboding came down upon us, which got heavier and heavier as we neared the spires of the cathedral. It was a weird sort of foreboding. Not so much full of menace as full of something between hopelessness and self-loathing.

You are inadequate, deficient, faulty, incapable, stunted.

You always will be.

There is no joy, no triumph, no cheer, no bliss, no satisfaction.

And never will be.

Around then—still two blocks from the cathedral—we all began stumbling; and, before long, started falling to our knees. Soft moans escaped from our lips.

Well, all except those of Schrödinger’s Cat. She started jittering all over the place. Aimlessly, so far as I could tell. Then, after maybe half a minute of this, she jittered over to Greyboar—he’d managed to get back on his feet again—and said, “We need to get out of here. This is nothing we can handle on our own.”

There is only failure, fault, loss, contempt, dismissal, decline, defeat.

Stretching to eternity. Such is your existence. Such is your destiny.

“Move!” she shouted. “Move now.”

I got up, reached over, and helped Jenny and Angela to their feet. I began to guide them toward the coach—using the term “guide” pretty loosely. Our progress was more or less three steps forward, two steps back, five steps—no, stumbles—to the side.

I heard Greyboar bellowing and looked back. It seemed the numbskull still wanted to fight whatever hideous thing was lurking in that cathedral, but the Cat was driving him back by the crude expedient of smacking him on the head, shoulders, belly, you name the body part, using the blades of her lajatang for the purpose.

Thankfully, she was smiting him with the flat of the blades. I’d seen her use that weapon the way it was intended to be used. It made me think of a two-legged shredder.

If it had been anyone else doing that, Greyboar would have already broken multiple bones in their body. But this was his true love, after all—and besides, all she was doing was trying to save the cretin from his own cretinhood.

By now, the girls and I had gotten far enough away from the cathedral that I could feel the horror’s grip loosening on us. So, I gave them a little final push and turned back to help the Cat.

Immediately, I was driven to my knees.

You are a pitiful specimen of incompetence and ineptitude, doomed to mediocrity in all things. Your life is and will forever be a dreary miasma. You will long—in vain—to achieve fourth-rate status in any trade or profession you choose to follow. You will long—in vain—for any satisfaction in your personal life. Joy, happiness, exhilaration, even simple contentment: abandon any hope for them now. They are and will forever be beyond your reach.

I managed to struggle upright—barely. By then, thankfully, the Cat had driven Greyboar far enough away from the cathedral that he was able to shuffle along on his own. I’d done my duty as a Hero, Sidekick well enough, I figured. I turned back toward the coach.

Once all of us were in the coach, Oscar set off down the road, moving as fast as the vehicle allowed—which was pretty damn fast. We’d bought that coach back in our salad days as successful entrepreneurs.

* * *

Five miles or so down the road, Greyboar ordered Oscar to stop the coach.

“What do we do now?” he demanded. “My professional ethics as a Hero, Excelsior don’t allow me to just up and quit on a Calling. Come hell or high water—do or die—I’ve got to keep at it.”

So did I, according to the rules of the Heroes Guild, although I didn’t see any need to say it out loud.

“You can’t take that thing—whatever it is—just with your thumbs, Greyboar!” protested Jenny. “There’s magic involved here.”

“Which means we need a sorcerer,” said Angela.

Oh, no. I could see it coming…

“Lucky for us, we know the best sorcerer in the whole world!” said Jenny.

“Except for maybe God’s Own Tooth.” Greyboar turned to me. “What do you say, Ignace? And where is Zulkeh these days, anyway?”

Zulkeh of Goimr, physician. The world’s most puissant sorcerer… yeah, maybe. The world’s most insufferable egotistical windbag, for a certainty.

I sighed. “He’s in Murraine, I heard. Doing some sort of investigation that won’t mean anything to anyone except himself.”

“What a piece of luck!” exclaimed Jenny. “Murraine’s not far from here.”

Yeah, piece of luck. A day’s ride, by coach. One short, little twenty-four day before being afflicted—

“Okay,” I said. Windbaggery couldn’t actually kill you, after all, even though it could make you wish you were dead.

* * *

“Ridiculous,” pronounced the wizard. “Absurd. I am supposed to abandon my imperative studies in order to assist you in dealing with some pastoral nuisance? You have taken leave of your senses!”

His glowering gaze swept across all of us. “Each and every one of you. Mad as the proverbial hatter.”

I wasn’t paying much attention to him, though. I knew from experience that before Zulkeh would agree to do something, you’d have to listen to his long perorations on eighteen subjects under the sun, precious few of which had much to do with the subject at hand. The wizard was the sort of pedant who, if you took him out to dinner at a restaurant, would spend the first half hour giving you the history of the term “restaurant,” most of which would focus on its inadequacy compared to the term he preferred, which he’d uncovered while investigating an obscure dialect of a long-dead language whose script only he could read.

Then he’d complain about the menu, explaining that a properly organized one would present the foods not in the order in which they’d be eaten—appetizer; salad; soup; main course; dessert—but according to which food group they belonged to—grains; meats; vegetables; dairy products—except that the commonly accepted food groups were grossly erroneous because they were based on the shallow thinking of such clods as farmers, grocers, butchers, and other proletarians, instead of the ontological principles enunciated by the great ancient culinary scholar Julia Sfondrati-Piccolomini.

About midway through Zulkeh’s rant on the effrontery involved in disturbing a great mage in mid-scrutiny of whatever silly damn thing he was studying, Shelyid hustled into the salon bearing a huge tray laden with various snacks and beverages. The dwarf was the sorcerer’s apprentice, valet; servant; porter; aide; caretaker—you name it, and if it involved practical matters and manual labor, Shelyid was the one who’d be handling it. He was a pretty nice kid, too.

“Here, everybody,” he said. “You’ll need this to keep up your strength while the professor expounds.”

Professor was the appellation Shelyid used to refer to Zulkeh. The wizard himself would have much preferred “master,” but Shelyid had a labor contract that spelled out just about everything concerning his rights and responsibilities. The notorious malcontents Les Six had negotiated it for him, and the first thing they’d done was get rid of that “master” business. Prior to their intervention, Shelyid’s position in life had been indistinguishable from “galley slave.”

“I see you’ve come up in the world,” I said, after he set the tray down on a coffee table that was about the size of a small atoll. I waved my hand, indicated the salon we were currently situated in, which had taken a while to get to from the ornate front door of the wizard’s domicile. “The last place you guys were living in—”

“Don’t speak of it!” said Shelyid, raising his hand. “The memory is still painful. I had to keep the place clean, remember?”

He looked around the room, beaming. “We’re just renting, but even after we return to New Sfinctr we’ll be able to get a much better place than that overgrown shack we had on the docks. I found us a new revenue source that’s a lot more reliable—more remunerative, too—than the professor’s slapdash… well, you can hardly call it ‘finances.’ Be like calling an alley cat a majestic king of the jungle because it’s got some stripes.”

I would have pursued the matter right then and there—finances being recognized by all sane men as the true harmony of the spheres—but Zulkeh chose that moment to bring his temper tantrum to its peak.

“No! Under no circumstances! I shall not! Is my earth-shaking research project to be brought low by a mere village pest? I think not, sirrahs! I think not!”

“’Scuse me,” muttered Shelyid. He advanced upon the windbag. “Hold on a moment, Professor. Judging from all past experience, you’re bound to need a favor from Greyboar fairly soon. ‘Favor’ being a euphemism for a cartilage and bone crushing squeeze or two. Or three. Or it could easily be four. That being the case, doesn’t it make sense to store up a favor of your own? Otherwise—you know how much you hate doing it—you’ll be driven to plead, implore, and beseech when you need Greyboar’s help. Your enemies and rivals will call you a beggar.”

The wizard glared down at him, his ridiculous conical hat quivering with outrage. “I have no rivals, impudent gnome! Enemies, yes. Untold numbers of them. Envious and resentful inferiors, the lot! Rivals, no.”

“As you say, Professor. I’ll see to the preparation of your bag for the trip. Do you wish to bring the usual? That is to say, everything?”

The windbag’s glare turned into a scowl. Shelyid had boxed him in and he knew it. He would need to ask Greyboar for a favor, soon enough—and the great Zulkeh of Goimr, physician, probably hated being thought a beggar more than he hated most anything else. And he hated as many things as there are stars in the skies, it seemed like.

“Of course, I need everything. See to it, loyal minion.”

In days gone by, Zulkeh would have called the dwarf his loyal but stupid apprentice, but that too was now forbidden in the labor contract.

I’d been through this experience before, more than once, so I sprawled in comfort on the most comfortable looking divan in the room. We’d be a while.

For the next several hours, Shelyid scurried about packing the wizard’s paraphernalia into the monstrous sack that Zulkeh considered his travel bag. That paraphernalia consisted of a multitude of scrolls heaped untidily upon work benches and shelves, the stone figurines and clay tablets scattered about the floor, the thick leather-bound tomes of great weight stacked precariously hither and yon, the vials, beakers, jars, jugs, amulets, talismans, vessels, bowls, ladles, retorts, pincers, tweezers, pins, the bound bundles of sandalwood, ebony and dwarf pine, the bags and sacks of incense, herbs, mushrooms, dried grue of animal parts, the bottles of every shape and description filled with liquids of multitudinous variety of color, content and viscosity, the charms, the curios, the relics, the urns of meteor dust, the cartons of saints’ bones and the coffers of criminals’ skulls, and all the other artifacts of stupendous thaumaturgic potency crammed into every nook and cranny of every niche, room, closet, and hallway, not excluding the heavy iron engines in the lower vaults.

By the time he was done, sundown had arrived. None of us—especially Oscar and the boys—wanted to travel at night in a coach as heavily laden as this one would be. So Zulkeh began expounding on the pleasures and health benefits of sleeping outside. Thankfully, Shelyid bypassed all that nonsense by pointing out that their new lodgings had plenty of rooms available for all.

Well, excepting Oscar and the boys. But they were quite accustomed to sleeping in the coach.

“Can’t remember the last time—or the first time, for that matter—that I paid a grasping and greedy innkeeper for a place to sleep,” said Oscar. He eyed Shelyid. “And we usually steal our food.”

“Won’t need to do that here!” the dwarf said cheerily. “I’ll bring you something shortly. Just don’t mention it to the professor.”

Like I said, a nice kid.

* * *

The following day, we set out for Sylvan Springs—which all of us except Patty were now calling Suffering Shanties. Patty didn’t call her wretched town anything on account of she didn’t utter more than a handful of sentences a day, and then only in whispers to Jenny and Angela.

We made good progress, given the wretched state of the so-called roads, but by the time evening arrived we were still some distance from the town of misery. In any event, no one—not even the wizard, who was prone to excessive self-esteem—wanted to come to grips with whatever horror lurked in the cathedral after nightfall.

So, we found a tavern. Using the term generously. To my delight and relief, however, Shelyid rummaged through the wizard’s sack and came out with an old cantrip titled Bugs, begone! Once Zulkeh intoned it, all manner of creatures with excessive legs promptly fled the premises. So, we even managed to get a decent night’s sleep.

Well. Not me. Angela and Jenny were in a frisky mood again. But, manfully, I did not complain.

* * *

We were off again the next morning. “Bright and early,” as the idiot old saw would have it, ignoring the obvious truth that “early” and “bright” is a ridiculous combination of words.

Oscar brought the coach to a stop right about the same spot he’d done in our first visit. Patty stayed with the boys in the coach. The rest of us sallied forth.

It might be more apt to say that all of us except Shelyid sallied forth. Burdened by that enormous sack, his progress was more in the way of a staggering lurch. How someone his size even managed to hoist the thing onto his back was a mystery. He was incredibly strong.

Right about the same distance from the cathedral as had been the case on our previous visit, the sense of foreboding made itself felt again. Zulkeh immediately ordered a halt.

“Before all else, I need to determine the nature of this menace,” he said. “Shelyid, fetch me the Encyclopedia of Perils, Hazards, Jeopardies and Maledictions.”

The dwarf plunged into the sack and emerged a couple of minutes later with a thick leather tome. After handing it to the wizard, Zulkeh spent some time flipping through the pages.

At length, he seemed satisfied. “I believe we are confronted with one of three vexations. Normally, I would be inclined to think we faced either a wightwoe or a mispecter. Either of which”—he waved his hand dismissively—“would be child’s play for a sorcerer of my caliber. But as a rule, those pathetic vermin of the chthonian persuasion avoid cathedrals, churches, temples—anything resting on sanctified soil. So…”

He stroked his long beard. “I fear we may be facing a far more malevolent power.”

“How do we find out?’ asked Greyboar.

“Pah! ’Tis simple enough. Joyce Laebmauntsforscynneweëld’s ‘Finnegan’s Wake Up’ will rouse the monster, if it’s what I think it is.”

“Just give me a minute!” said Shelyid, diving back into the sack. In less time than that, he reemerged with a slim volume in his hand along with a jewel box and what looked like a small religious icon. “I brought the Molly and the portrait as well.”

“I shan’t need the portrait. The Molly may come in handy.” Zulkeh reached out and took the jewel box. Then, striding forth a few steps, opened the box and cast from it what looked like tiny diamonds. As soon as the jewels—if that’s what they were—struck the ground they began chanting the following verse:

riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation

a way a lone a last a loved a long the

riverrun, past Eve and Adam’s, from swerve of shore to bend of bay, brings us by a commodius vicus of recirculation

a way a lone a last—

A tremendous hissing sound emerged from the cathedral. That was followed by a clattering of what sounded like the boots of an army. A moment later, the cathedral doors burst open, and a hideous creature emerged into the daylight.

What did it look like? Well, imagine a centaur (of sorts) the size of a gigantic centipede, from whose forward portion emerged a torso that looked more like a skeleton than something formed of flesh. Perhaps worst of all was the head, which looked surprisingly human—but whose facial expression was the quintessence of contempt, derision, and disapproval.

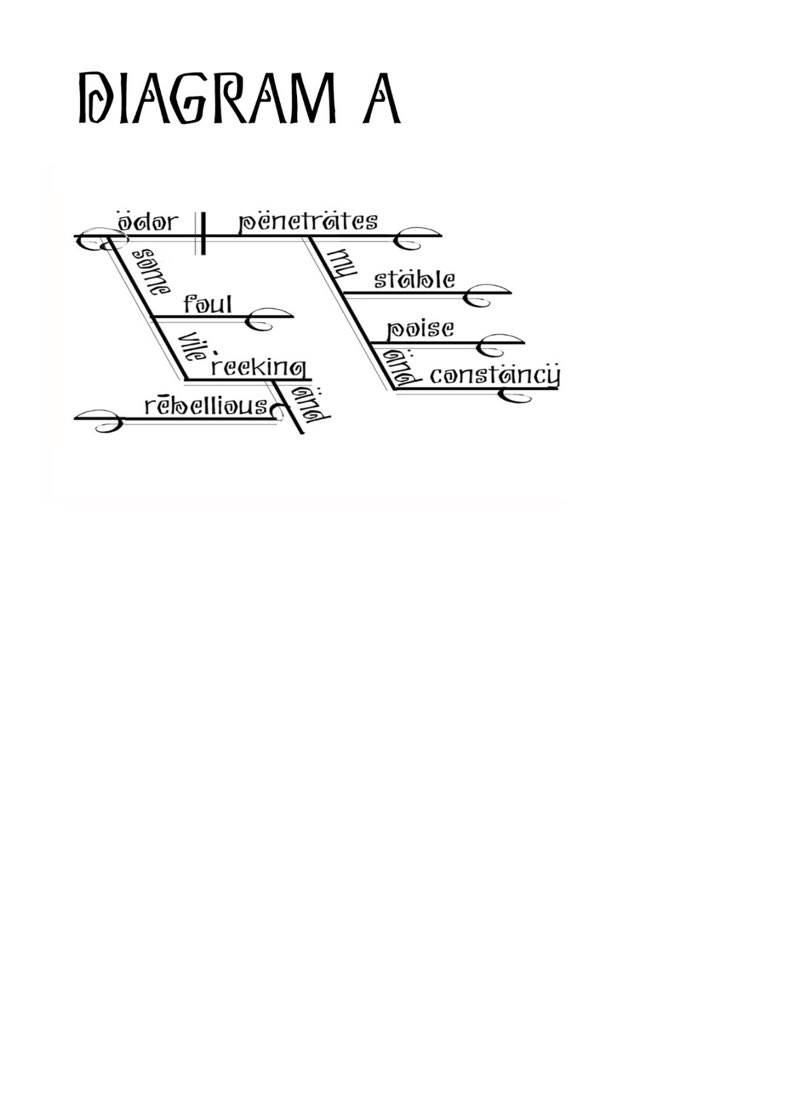

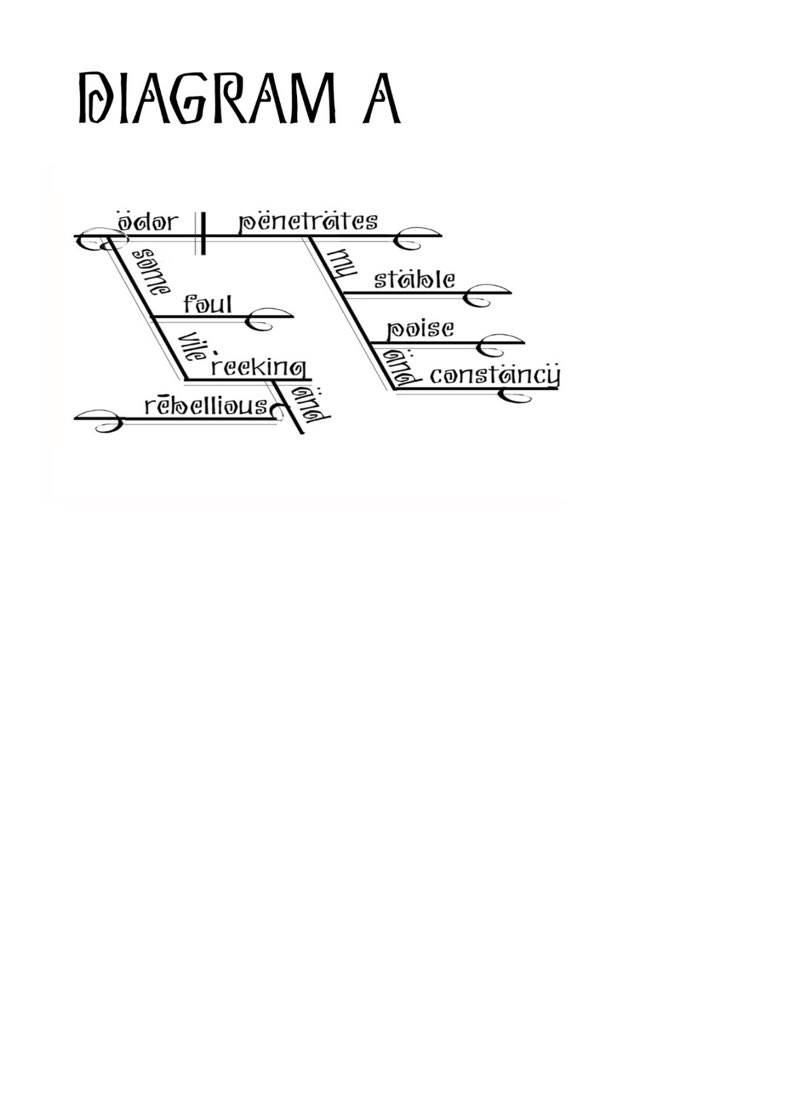

The monster bellowed the following:

I was driven to my knees by the sheer force of the monster’s disapproval. So were all the others except Zulkeh and Shelyid. The wizard might have stepped back a pace or two; the dwarf didn’t seem to budge at all—allowing for the tight clasp he had on the fabric of the sorcerer’s sack.

“Oh, would you!” cried out Zulkeh. “Well, then—take this, you vile caitiff!”

The sorcerer capered forward and began what looked for all the world like one of those energetic heathen dances favored by primitive barbarian tribes. With each step, he called out the following words:

“swoop (shrill collective myth) into thy grave

“merely to toil the scale to shrillerness

“per every madge and mabel dick and dave”

Again, the monster issued a great hiss. But it also seemed to stagger to one side, as if its ugly hairy legs had lost their footing.

“Haha!” yelped Zulkeh, his tone triumphant. “Can’t stand up to the poetic chaos, can you?”

He turned back toward Shelyid. “As I suspected—it’s a Grammarian. Horrid things. They wreak havoc among children, especially. Strip the poor tykes of all joy, all spontaneity, all carefree welcome of the world. Shackle them in shrouds of inadequacy, webs of hopelessness, and chains of glum foreknowledge of an empty life to come. But—!”

He capered a few more steps in his dance. “The verses of e.e. sfondrati-piccolomini always drive them mad. Ha!”

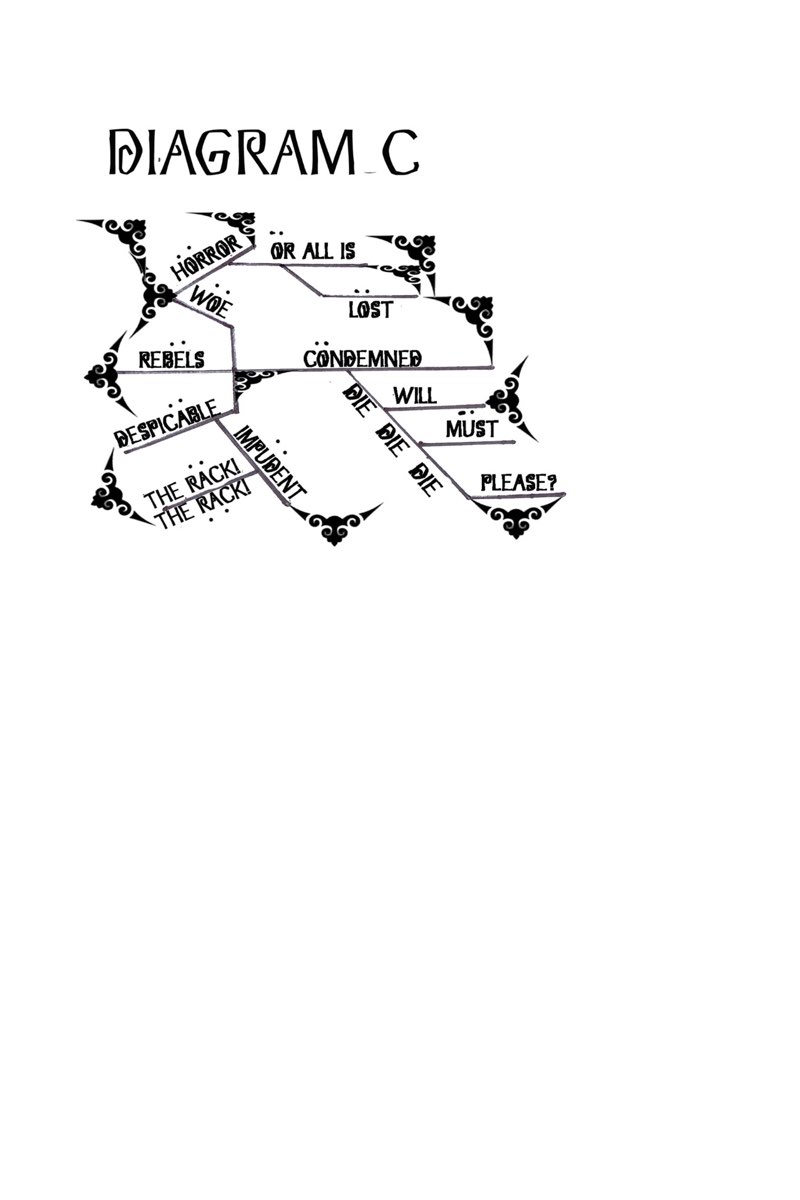

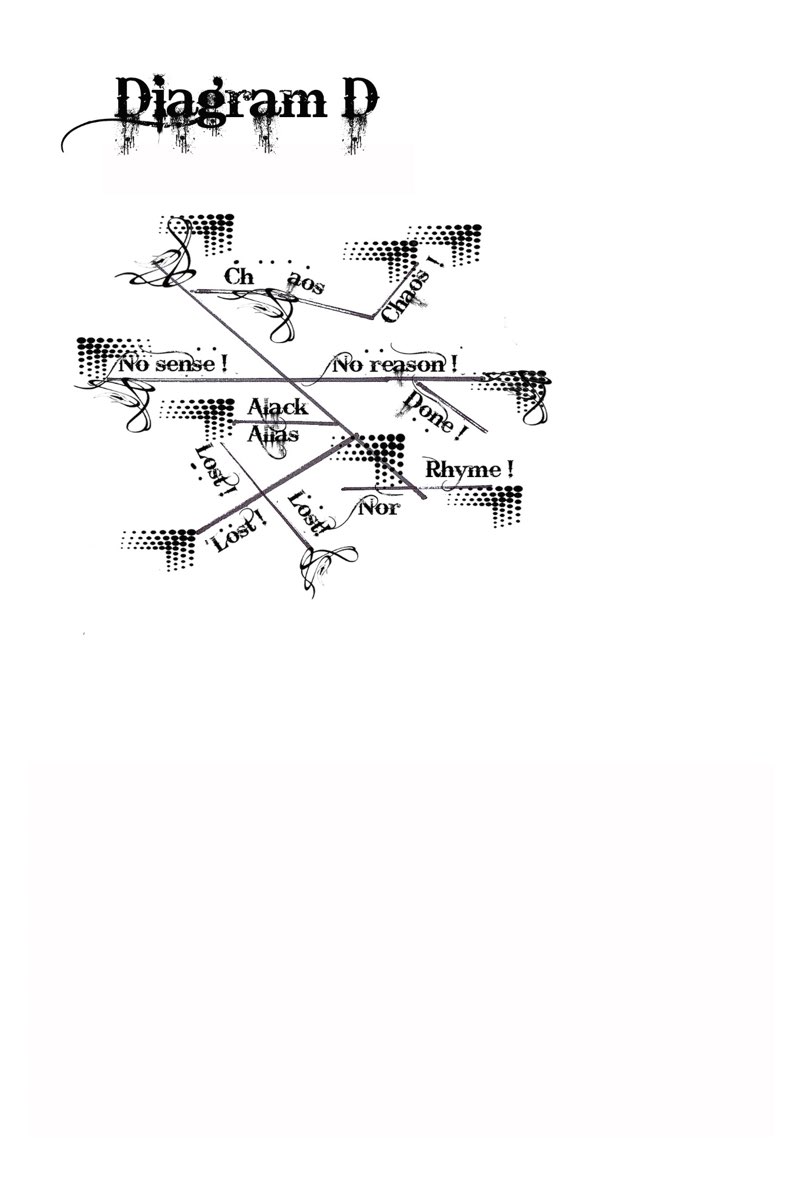

In the distance, the Grammarian appeared to have recovered its poise. Some of it, at least. It scurried forward on its multitude of legs, and now screeched:

My spirits immediately rose. It was obvious, even to a nonpareil non-wizard like me, that the Grammarian was badly wounded.

“Shelyid! The Molly!”

The dwarf handed Zulkeh the slim volume. Zulkeh immediately flipped it open and chose—completely at random, so far as I could tell—to read the following passage. Very, very loudly.

“or shall I wear a red yes and how he kissed me under the Moorish wall and I thought well as well him as another and then I asked him with my eyes to ask again yes and then he asked me would I yes to say yes”

The Grammarian howled, then suddenly collapsed, its dozens of legs flopping around with seemingly no rhythm or coordination at all. A moment later, it shrieked:

“He’s done for, Professor!” said Shelyid gleefully. “Drive home the coup de grâce! What’ll it be? Faulkner Laebmauntsforscynneweëld’s The Sound and the Fuzzy? Woolf Sfondrati-Piccolomini’s Mrs. Thataway?”

“No. For this wretched Grammarian, nothing will do except verses from the Carroller.”

“I’ll fetch them right off!” The dwarf started climbing back into the sack.

“Bah! Desist, my loyal but needlessly energetic apprentice. I had the Carroller’s wisdom memorized by the time I was seven.”

I was amazed to see the wizard then do a perfect pirouette. Once, twice, thrice. Following which he chanted:

“The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame,

“Came whiffling through the tulgey wood,

“And burbled as it came!”

The Grammarian tried to retreat back into the cathedral, dragging itself with flailing limbs. To no avail. Before it got barely started it began convulsing, following which a piteous wail came forth.

Greyboar saw his chance and rushed forward. A moment later he was throttling the monster.

“A waste of effort!” shouted Zulkeh. “’Tis impossible to silence a Grammarian outright! Go for the skull! It’s quite fragile!”

The strangler’s—sorry, Hero’s—great hands shifted to the withered skull.

Crack. Crack. Crunch. Just a cloud of dust remained.

“’Tis due to the horror’s obsessions,” Zulkeh explained. “Such traits invariably lead to brittle craniums.”

I refrained from comments about pots calling kettles black.

“Don’t touch me until you’ve scrubbed your hands!” the Cat hollered.

Within less than a minute, a few people began making their appearance in the square before the cathedral, emerging from whatever hiding places they’d managed to find. They moved slowly and were all gaunt to the point of being emaciated. They gathered some distance from the Grammarian’s carcass, still with no expressions on their faces beyond despair.

By then, Oscar had brought up the coach and Patty emerged from it. Her gaze was fixed upon the dead monster.

Jenny and Angela went over to her. “Do you want to look for your family?” they asked.

The little girl shook her head. “They’re all gone. Forever gone.”

A great dread seized my heart.

Sure enough—

“You poor thing!” exclaimed Angela.

“But don’t worry,” said Jenny. “We’ll take you in.”

Marvelous. Another mouth to feed. With what?

But I didn’t think to argue the matter. I’d lose the quarrel. Not even Greyboar would side with me, and the Cat… I shuddered to think what that madwoman might do.

“All right,” I said. “Let’s be off.” Before my kind but impractical ladies offer shelter to anyone else in this miserable rustic ruin.

“Not just yet, Ignace!” That from Shelyid, who was climbing out of the sack again. This time, to my surprise, holding an easel, a small canvas, and what looked like a cup full of pencils.

The dwarf pointed at the Grammarian’s remains. “You make a lot more money if you accompany your tale of adventure with a few drawings. Mine aren’t that good, but the audience isn’t really so fussy.”

“What are you talking about?”

“I told you. I found a new and much better source of income. They’re called Champeon accounts. You set them up—costs nothing—with an amulet from the Wizard Wide Weft.”

“I never heard of it.”

Shelyid gave me a sideways look. “Meaning no offense, Ignace, but you’re not exactly knowledgeable when it comes to modern advancements.”

“Modern advancements!” I jeered. “What? Have they come up with something better than ale?”

“I rest my case.” Shelyid started toward the Grammarian’s remains. So far, only a single rat had approached them—and it fled before it got within two yards.

Before the dwarf took three steps, though, Patty spoke up.

“I like to draw,” she said. It was the only thing she’d said in the time I’d known her that seemed to have any spirit to it.

Shelyid turned and looked at her. “Well, come with me, then. Let’s see what you can do.”

* * *

For the next hour, Shelyid and Patty took turns at the easel, each doing their own pencil portrait of the expired fiend. When they were done, everyone in our party gathered around to examine the results.

The opinion was unanimous. “Patty’s a lot better than you are, Shelyid.”

“Sure is!” he said cheerfully.

He then turned to me. “Since you’re going to be taking care of her anyway, you ought to make her a partner in your new Champeon business.”

I scowled “What—”

“That’s a great idea!” exclaimed Jenny.

“Yes, it is,” chimed in Angela. She started wagging her finger under my nose. “And don’t whine, Ignace! I’ve been talking to Shelyid about how these Champeon things work. All you have to do is tell tall tales about the exploits of Greyboar and his friends and post them along with Patty’s drawings. He says as long as you can lie well enough, the contributions will come flowing in.”

“And if there’s one thing you’re a champion of,” said Jenny, “it’s lying.”

Angela smacked her shoulder. “Be nice! When it’s professional lying they call it mendacity.”

I was tempted to protest. But…

I do have a natural talent for embellishing and improving upon drab and humdrum data. Tedious stuff, facts.

I studied the girl’s drawing again. She really was pretty damn good.

Maybe…

“Let’s be off!” commanded the Cat. “I want to be home before Ignace starts thinking too heavily, or we’ll get a broken axle.”

* * *

No more than two months later things were looking up! To my surprise—okay, I’ll admit it, I’m not all-seeing when it comes to money—Shelyid turned out to be right. As soon as I set up our Champeon account, money started flowing in. Not as much as we used to make throttling people, but you can’t expect miracles. Our income was still much better and more stable than it had been.

I credit myself with the nifty byline:

The Great Greyboar

Still Has Thumbs, and Now a Hero!

(Excelsior)

The only fly in the ointment was that Jenny and Angela insisted on becoming Patty’s managers.

“What for?” I demanded. “I was planning to do that myself. I’m the experienced manager here, aren’t I?”

Both of my ladies gave me the beady eye.

“In other words, you’ll negotiate with yourself over how much of a percentage Patty gets,” said Angela.

“Well…”

“What part of the phrase ‘conflict of interest’ are you having the most trouble with, Ignace?” Those uncharitable words came from Jenny.

“Fat chance,” they now said in unison.

Angela: “We will serve as the little girl’s agents.”

Jenny: “Who knows the tricks and deceits of the management involved better than we do?”

“I’m hurt! Cut to the quick!”

Jenny yanked up my shirt and started inspecting me. “You see any bleeding wounds, Angela?”

“Not a one.”

Then they insisted that Patty had to get one-third of the proceeds!

“Ridiculous!” I said. “She’s just a paid contractor.”

“A, she’s not paid,” said Jenny.

“B, her drawings are better than your prose,” said Angela.

“C, they’re way more accurate, too.”

I stumped around for a bit, scowling my best scowl. “Then at least she has to start paying rent!”

“What?” exclaimed Jenny. “The girl’s not even ten years old and you want to start charging her rent?”

“Her percentage just went up to thirty-five percent,” hissed Angela.

I opened my mouth to advance the cause of reason.

“And if you keep arguing” said Jenny, “we’ll put you on an affection diet.”

“Starvation diet,” clarified Angela.

My mouth closed. Dammit, that was cheating. But I knew they were serious about it.

And…

Push comes to shove, even for me, affection outranks lucre.

Well, theirs does, anyway.