X

Tomograms, thermograms, sonograms, mammograms, and fluoroscopic “movies.”

Although this catalogue reads like a list of options that some futuristic Western Union might provide its customers, these exotic-sounding “grams” are in reality an integral part of the detection-and-diagnosis procedures at the West Georgia Cancer Clinic in Ladysmith.

Stevenson Crye, 35, of nearby Barclay—her friends call her Stevie—came to know the sophisticated machines that perform these vital diagnostic functions during her husband’s unsuccessful treatment. Although the clinic also has an arsenal of machines designed to cure as well as to diagnose cancer, Mrs. Crye’s husband rejected the possibility of hope in favor of a noble despair.

“He simply gave up,” said Mrs. Crye Tuesday. “He ran out on us.”

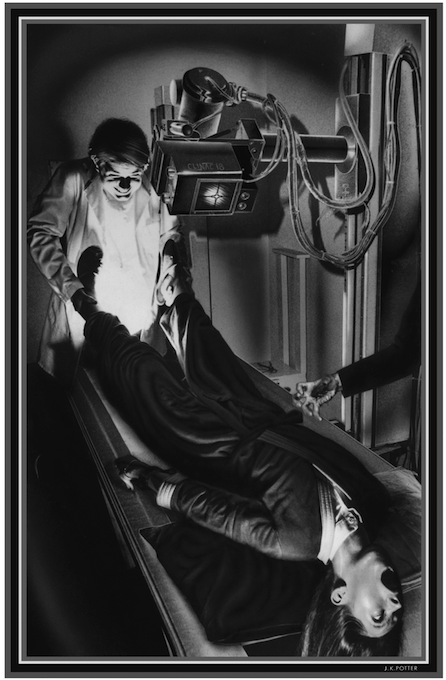

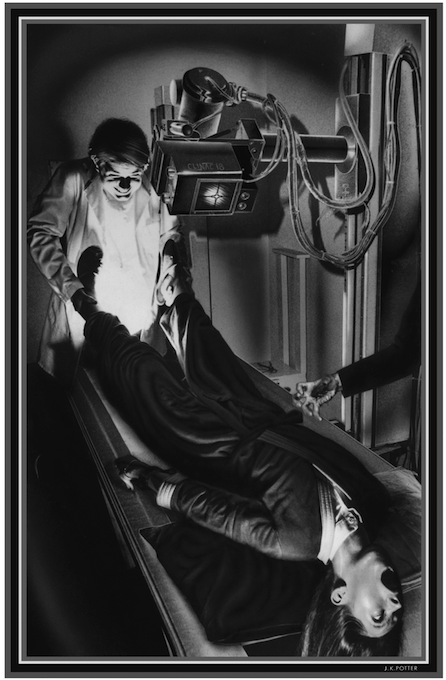

Early this morning, Theodore Crye, Sr., who died in 1980 at the age of 39, answered this charge. Forsaking the family plot in the Barclay cemetery, Crye returned to the Ladysmith clinic to meet his wife in the same downstairs treatment room where he once underwent radiation therapy beneath the tumor-destroying beam of the Clinac 18.

Swollen-tongued and eyeless, Crye put a decomposing hand on this floor-to-ceiling unit and detailed its features for his horrified wife.

“Developed by the Varian Co. in Palo Alto, Calif., the Clinac 18 is known by its manufacturer as a ‘standing-wave linear accelerator,’ ” said Crye. “It speeds electrons around an interior track to shape a beam that eventually generates X-rays.

“Only X-rays of one intensity must come out of the machine and hit the patient,” Crye continued. “Certain organs can tolerate only so much radiation, and people vary in their tolerance to radiation, just as some people get sunburns more rapidly than others.”

Clad in her sleeping gown and a pair of powder-blue mules, Mrs. Crye appeared distraught and inattentive through her dead husband’s recital. Dr. Elsa Kensington, director of the West Georgia facility, said that her friend would probably have bolted from the treatment room if not for the calming presence of clinic dosimetrist Seaton Benecke, 26, of Columbus.

“Every morning I run a series of ‘output checks’ on the Clinac 18 to make sure its dosage emissions are constant and controllable,” Benecke told Mrs. Crye. “I also make ‘patient contours’—images of the abdominal region outlined on graph paper with a piece of wire—to find the proper dosage for each patient.

“I plot this amount with a radiation-therapy planning computer. We once did dosage plotting by hand, but it took hours and the need to be exact is so great that the job could be truly nerve-racking.”

“You’re not Ted,” Mrs. Crye accused her husband’s corpse. “You don’t talk like Seaton Benecke,” she accused the clinic dosimetrist.

Ignoring his wife’s objections, Crye said, “Benecke discovered that I had a very low tolerance to radiation. Ionization occurred in the tissues through which the Clinac 18’s beam had to pass to reach my tumor, and my body began to fall apart from the inside.”

Crye then invited his wife to lie down under the movable eye of the Clinac 18. When she refused, he and Benecke firmly placed her on the pallet beneath it. The facility’s space-age acoustics kept her screams from being heard beyond the treatment room.

“I’m just giving it a special twist here,” Benecke said, turning on the accelerator. “Deepness is what I like. A beam from the Clinac 18 can go down as deep as fifteen centimeters before ‘exploding’ through the tumor-bearing area. That’s what I really like.”

“I fell apart down deep,” Crye said, a dead hand on his wife’s forehead. “If I appeared to give up, Stevie, it was only because