IX

Stevenson Crye could never remember her dreams, but this one, as she endured it, lashed her with a multitude of familiar anxieties and a few completely fresh ones. Groping for a handle on her whereabouts, chagrined that the ghastly imagery of her dreams had again eluded her, she awoke in a bath of sweat. As usual, she had washed ashore ignorant of the size and number of the nightmarish jellyfish whose stings had scourged her. She kicked aside her blankets and lay in the frigid gloom trying to recover her wits. Her sweat began to dry, her body to convulse. She grabbed her shabby housecoat from the bottom of the bed and hurriedly snugged it about her shoulders.

At which point she heard the Exceleriter in the next room, her study, clacking away like a set of those grotesque plastic dentures you could buy in novelty stores . . . or like her own chattering teeth.

“No,” Stevie said. “It’s something else.”

After all, your ears could fool you. The whine of a vacuum cleaner in another room could sound like an ambulance wail, bacon sizzling in a skillet like rain on a summer pavement. Maybe this typewriterly clacking was nothing but tree branches scraping her study window or squirrels clambering through the uninsulated walls. But, as Stevie well knew, neither of these sounds came accompanied by the distinctive ping! of a margin-stop bell or the smooth ker-thump! of a returning carriage. Her ears had not deceived her. The Exceleriter was working independent of human control, percussing out its alien derangement.

I left it on, Stevie thought. I forgot to turn it off, a key was accidentally depressed, and it’s been stuck like a broken automobile horn ever since I fell asleep. A mechanical explanation for a simple, although weird, mechanical problem. Of course this explanation still doesn’t account for the thumping regularity of the carriage reflex—but it’s got to be close to what’s going on in there. It’s got to be.

Stevie did not want to go into her study to check. She wanted the Exceleriter to stop of its own accord. She wanted to slide back into her bed and forget the whole incident. The night—especially a winter’s night—imbued even the simplest phenomenon with mystery. In the morning she would be less prone to extrapolate nonsense from her muddled senses. But the Exceleriter did not stop, and Stevie was now sufficiently awake to know that its possession—its maddening midnight activity—would seem no less mysterious in the bleak light of dawn. Eventually, now or later, she must cross her study’s threshold.

When she turned on the hall light, the typing ceased. Quick glances into Teddy’s and Marella’s rooms assured her that the children had heard nothing; they lay huddled under their GE blankets, hot-wired for sleep, mercifully heedless of her apprehension. Thank God for that.

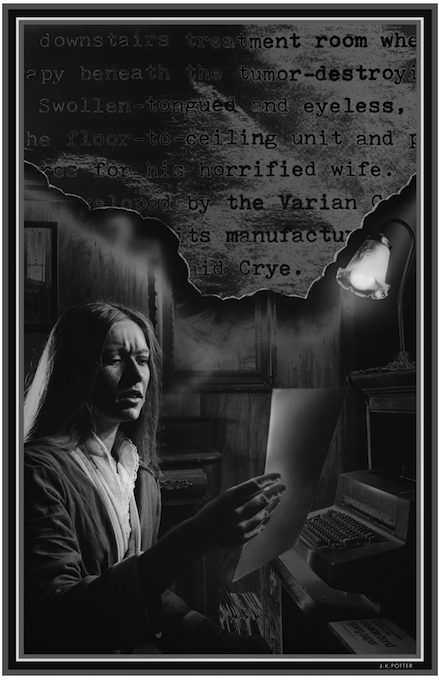

Sighing her relief, Stevie pushed the door to her study inward. In the light filtering in from the hall she saw that the page carelessly left in the typewriter had curled back over the cylinder almost to the full extent of its length. The Exceleriter had advanced it that far. Phalanxes of alphabetical characters covered its pale surface. Stevie strolled cautiously to her rolltop and switched on her brass desk lamp. There, her breath drifting in puffs through the halo produced by the lamp, she fumbled the page from the top of the machine, lifted it into the light, and began to read. . . .