CHAPTER III

THE ANTE-CHAMBER OF THE POLE.

THE three chief witnesses of the drama were silent as to this last episode in a singularly exciting adventure. But Isabelle, who was much impressed by it, saw Hubert and Guerbraz exchange looks.

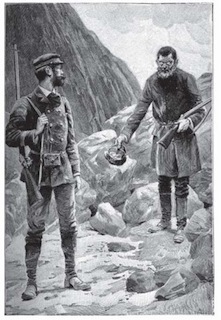

The two men had known each other for many years. Guerbraz, although older than Hubert, had been at sea under him when he was a midshipman. It was evident that their companion’s clumsiness appeared suspicious. Schnecker had fired when there was no reason for it. The Breton’s danger had been ended by Isabelle’s carbine, and the two surviving beasts had time to disappear behind a low hill..

The naturalist, however, advanced, cap in hand, bowing very low, and with his most obsequious smile.

He sought to excuse himself.

“It seems I might have been the cause of a misfortune! Pardon me, pray. I am very short-sighted. I will not use a gun again.”

“Then you will do well, sir!” said the young man, who was not of a very patient nature. And turning his back on the chemist, he quickened his pace so as to return to the station in Isabelle’s company.

Attracted by the reports of the guns, De Keralio was already on the way towards them, as were also Doctor Servan and the five other sailors.

To these was given the task of skinning and cutting up the beasts, so as to leave no time for the flesh to contract the odour of musk which would have made them uneatable. This task was promptly accomplished, and four hundred kilos of fresh meat were taken into store.

On their return to Fort Esperance, Hubert immediately went to his future father-in-law, with the doctor and Guerbraz, in order that they might talk over together the serious occurrence which had just taken place.

The conference was an exciting one. De Keralio, who was very good-natured, could not believe in an act of malevolence. It appeared to him so unlikely.

“I know,” he said, “that our companion is remarkably shortsighted.”

“ Bah!” said Hubert, “when a man is as short-sighted that he does not venture to shoot; and I really do not understand how you can send a bullet within a foot of a man’s face, and take the man for an ox.”

And he added, with that animation which always distinguished him,—

“We shall have to keep our eyes open, or the worthy Schnecker will be taking us all for beasts.”

His companions laughed. But the subject was too serious to be lost sight of so easily. De Keralio could not help exclaiming,—

“But what motive could he have for committing such a crime? We have never done him any harm. None of us has shown the slightest suspicion of him.”

“Pardon!” said Hubert, “there is one who has borne witness against him from the very first day. That is our brave Salvator.”

“Certainly,” said the doctor, seriously, “there is some weight in that argument. I consider the instinct of animals, and particularly

of dogs, infallible.”

He stopped, and addressing De Keralio, he said,—

“Whence came this bad shot of a chemist?”

”He came to me from Paris,” said De Keralio. “He came to me with the highest recommendations from well-known men, members of the institute or learned societies in the departments.”

“In that case,” said the thoughtful doctor, “if there was any criminal intention it can only be explained by a violent jealousy, one of those strangely low and vile sentiments which can be found in the human soul. A large measure of intelligence is no guarantee of a good heart or a fine character.”

“We must watch him all the same,” said De Keralio.

“I will take care of that,” said Guerbraz, quietly.

And thereupon they separated with an appointment for the study of the coasts and an examination of the maps.

To tell the truth these were most incomplete, and the expedition in its present quarters was really in face of the unknown. What they knew they only knew by supposition. The coast of Greenland is said to be very rugged above the 78th degree. The soundings taken at Spitzbergen have shown considerable depths, and it is evident that there is no land between the seventh degree of east longitude and the twentieth of west longitude.

The hypothesis of a vast sea, and therefore the more liable to the influence of warm currents and high tides, is a plausible one. From the top of the sea cliffs the explorers could see that the ocean was entirely free, and that their eyes lighted on no unknown land or any of those irregularities which in Kennedy Channel and Robeson Channel transform the western fiords into beds of glaciers destined to form icebergs. There was, therefore, every reason to suppose that a sea voyage would be possible in the coming spring.

The summer passed rapidly away, and the first signs of winter showed themselves more unmistakably. In the mornings and evenings there was formed on the surface of the water that sheet of thin friable ice which the Canadians call frazi. Besides, the night, the terrible polar night was approaching, and the midnight sun was sinking on the southern horizon. Towards the 15th of August, the glacial north wind had thickened the edging of the land to about three inches, and the never melting ledge of the shore had taken the characteristic blue tint of fresh stratifications.

The clothes required by this rapid lowering of the temperature were gradually assumed. To keep the men in full activity, Lieutenant D’Ermont gave them something to do in maintaining an open channel for the approaching return of the Polar Star. And during their leisure they constructed with all possible care the wings of the house, which by the 20th of August were ready for occupation.

Thence onwards all thoughts were concentrated on the return, and every day the anxious looks of the winterers were turned to the southern horizon.

The sea was covered with masses of ice of every conceivable size. It was evident that in the vast extent of the seas between Greenland and Spitzbergen, the formation of floes was a much slower process than in the bays and straits of North America.

Nevertheless with the continued descent of the thermometer, the imminence of the great congelation increased every hour. Coming down from the north they could see great bergs, regular mountains of ice with their escort of minor blocks and fragments of the icefield, which in freezing together would form the pack, properly so called. The mean temperature of the month of August was six degrees. It was still very agreeable for people who in the temperate zone were accustomed to twelve and fifteen in the depth of winter.

Isabelle never for a moment lost her vivacity or enthusiasm. She was even anxious for winter to come, as it would introduce her to so many grand experiences, astronomical and meteorological. Besides, would it not in turn introduce the spring when the sledges would be out on their explorations, if it were not possible to get the Polar Star herself nearer the pole?

De Keralio did not share this optimism with her. He bitterly regretted his surrender to his daughter’s caprice, and feared for her when the cold should come. The first snow, the insidious penetration of death under its most mournful aspect, brought a gloom over his thoughts as the gloom spread over the firmament which the sun was to desert for so many interminable months.

But now that the deed was done, now that Isabelle could not retreat from her daring decision, the father concealed his alarm for fear of decreasing her good humour, and lessening the mental and physical energy she would need to overcome the terrible trials of winter.

Daily the men had more to do. In one of his excursions towards Mount Petermann, D’Ermont had discovered a considerable coal deposit which Nature had brought to the surface and offered ready to their hands. From it they set to work to bring in enough for two winters. The valuable mineral was deposited in a heap against the annexes of the galleries, over which a special shed was built with planks and tarpaulins.

The return of the Polar Star was awaited with increasing impatience. Every day that elapsed made the anxiety greater for the Polar seas are full of strange caprices. Twice at least during three days the horizon had been veiled in deep mountains of mist, and it seemed as though the ship would find the way closed against her.

And it was with enthusiastic cheers that topman Kermaidic was welcomed on his descent from the look-out on the 22nd of August, about one o’clock in the afternoon. He had just sighted smoke. The wind was blowing from the south and clearing the vicinity of the coast. The icebergs were moving towards the east, in the direction of Spitzbergen. The ship could enter the fiord at the close of the day.

They were out in their calculations. Suddenly about five o’clock in the evening, just as the smoke of the Polar Star revealed her presence at less than three miles from the coast, the wind jumped round to the north-west and produced a rapid fall in the mercurial column. The thermometer, without any warning, went down to twenty degrees below zero.

The night had to be passed in cruel anxiety, and at ten o’clock next morning the ship was sighted two miles further to the south. The ice had increased eight inches in thickness during the night.

Fortunately the tide rose, driving back the floating blocks in such a way as to leave several channels for any ship wishing to enter the fiord. Aided by her ram and her coated hull, and the power of her engines, the Polar Star could clear a passage through the fragments which every moment threatened to obstruct her. At two o’clock precisely the ship forced her way in from the sea and cast anchor in Franz Josef fiord, at the foot of cliffs a thousand feet high, which sheltered her as well as Fort Esperance.

The inhabitants of the station ran out with cheers of joy to welcome the arrivals, and it was with most touching enthusiasm that they greeted those whom for an instant they had despaired of seeing again. The people on the ship betrayed the liveliest gratification at finding themselves ashore under a shelter so comfortable, built and arranged with every care, and in conformity with the most minute requirements of hygiene. That evening there was a banquet, where toasts were given with enthusiasm for the success of the expedition.

The next morning, everyone was afoot at ten o’clock, and De Keralio for the first time entering on his duties as commander-inchief, mustered his men so as to give them their orders.

Following the example of the English expedition of 1876, the officers resolved to distribute the men into detachments according to the work for which they were intended. Independently of their ordinary labours they were told off for certain general work, either in the interior of the fort or for the preparation of the exploring parties.

This assignment to stations was not the only business of the day. There was an inspection of the equipment and the weapons, and a medical inspection rendered obligatory by the necessity of assigning to each his full share of the work. This first muster roll showed that, irrespective of the officers there were thirty sailors and workmen, consisting of twenty Bretons and ten Canadians. Every man received a short Winchester rifle, sighted up to six hundred yards with a hundred and twenty cartridges, a revolver in the French pattern with ten packets of cartridges, a hunting knife, a short-handled axe with a brass guard for the edge, a case containing a four-bladed knife, scissors, needles and thread, comb and brush. The clothes consisted of three pairs of trousers of soft wool, three flannel shirts two knitted waistcoats and frocks, a fur coat, a cape with a hood, an otter-skin cap with neck-flap and ear-flaps, two pairs of wool mittens and a pair of furred gloves, a pair of leather boots for the fine season in addition to two pairs of moccasins, cloth leggings, and waterproof gaiters. The woollen socks were kept in store. They would only be given out to the men on an order from the chief of their squad.

In the magazine were left twelve fowling-pieces, which could be lent out to the best sportsmen of the party when required.

Besides the wooden cots and mattresses there was a sleeping bag in buffalo skin for every two men; in readiness tor the autumn and spring excursions there were twenty of these, ten others being put into store.

The dogs, to the number of forty, were landed on the first day, and Ouen Carré, the Canadian whaler, was entrusted with their education, which was anything but a sinecure for him.

The following days were devoted to the final stowage of the provisions left on board the Polar Star. The rudder was unshipped and laid on the deck. The screws. were even unshipped and the different sections of the shafts were well greased and wrapped in leather. The boats were all lashed firmly down. With similar precaution the lower masts of the ship were alone left standing and she was covered from one end to the other by a triple awning, all her openings being closed with the exception of the hatchway giving access below.

It was unanimously agreed that if the house was in any way damaged, refuge would be taken on board the Polar Star.

Finally, to preserve the hull by every means from the eventual pressure of the ice, it was defended by a cradle of steel, the bands of which interlapped in a series of St. Andrew’s crosses and interlaced with iron beams that were bedded in a frame of wood. Supported in this way, the ship could bear any pressure on her keel or flanks. The ends of the beams were hinged so as to yield a little; the beams would receive the shock below, and in response to the shock they would lift the ship bodily out of the water and hold her suspended. This was an invention of Marc D’Ermont’s which they were going to try for the first time.

The preparations being complete, nothing more could be done than to wait for the coming of the winter.

It was approaching quickly. The birds of passage which venture into these high latitudes in summer, could be seen returning south in long flocks. A few herds of wolves and arctic foxes appeared in the environs of Fort Esperance, and Isabelle had an opportunity of going in chase of these unwelcome visitors. But the hunters had their hunt for nothing. Neither wolves nor foxes would let them come near. They nevertheless killed a few dovekies some ptarmigan, now become rare as the summer neared its end, and half a dozen eider ducks.

On the 28th of August the stoves had to be lighted. The thermometer went down suddenly to zero. Dr. Servan, cheery, good-natured and enterprising, accorded Isabelle the title of “Directress of the Fine Arts and Public Games,” and inscribed his name under hers as organizing secretary. Thenceforth neither of them found work fail them, for in a polar expedition it is as important to keep the men in good spirits as in good physical health.

By their orders there had been brought all the needful materials for games which the English, that most practical of people, are never without, such as football, rackets, cricket, hockey, croquet, etc., etc. A space sixty yards across, chosen in a sheltered place, and swept and scraped with scrupulous attention, was the scene of these recreations. The carpenters of the crew surrounded it with a palisade of piles, and at every two yards were posts on which could be hooked electric lamps, Schnecker having offered to furnish all the light required during the stay at Fort Esperance.

This was not all. Under the able instruction of Ouen Carré and his assistant, Jim Clerikisen, an Eskimo from Frederikshat, the dogs were promptly put into training and the sight of the dogs out on the ice proved an additional attraction on the daily list of games. Among the Greenland dogs were six of great beauty belonging to the species known as Newfoundland in general and Labrador in particular. The Labrador dog is lower on the legs than the true Newfoundland. He is also generally stronger but assuredly much less gifted with docility and good manners. Theft is habitual to him, and he never knows respect for the property of others or sympathy for the misery of his neighbour.

The beautiful Salvator, who had come from France, only too openly showed his immense disdain, for the tribe of draught dogs. With regard to his congeners the Labradors he affected that species of haughty superiority of intellectual ascendency which townspeople assume over country folks. But he was a good king, and none thought of disputing his right to the crown. His unmistakable distinction, his truly prodigious strength, guaranteed him the respect of the semi-savages with whom he occasionally condescended to converse in the language usually known among his kind. The rest of his time was devoted to the particular service of his masters or rather his mistress. He was Isabelle’s assiduous companion, her escort in her occasionally venturesome explorations in the neighbourhood of the fort. Soon he became her guide, and his infallible instinct often warned her of danger, notably on one occasion when she would have come face to face with a gigantic bear in turning near the camp.

If Salvator was Isabelle’s four-footed bodyguard, she had a servant and friend no less devoted in Alain Guerbraz, the Breton sailor she had saved from the musk ox.

Guerbraz was one of those extraordinary men to whom God has given, to the astonishment of the human race, the prodigious strength which seems to have been the lot of the big pachyderms. The Breton was as powerful as a rhinoceros. He could juggle with half-hundredweights, break a bar of iron over the head of any animal whatsoever and when his hands, which were veritable grappling-irons were fixed on an object, you might cut them off but you certainly could not make them let go.

He had henceforth devoted to the defence of Isabelle de Keralio the life he owed to her brave and timely intervention. On her part she showed that she recognized this honest and genuine attachment, and on all occasions let it be seen that she trusted him. No better reward could this peaceful colossus nave for his devotion than the knowledge that Isabelle felt safe when under his guard.

The approach of the long polar night began to make its influence felt. The Canadians alone seemed to take no notice of it, accustomed as they were to the cold of the north. The others beheld, with a sort of terror, the days drawing in and the darkness increasing in the lengthy dawns and twilights. What would become of the gaiety and enthusiasm of the crew when the veil of darkness had definitely dropped on the northern hemisphere? Nervous and impressionable, Isabelle de Keralio was all the more to be praised for her efforts to hide her true feelings. As the winter took possession of its realm shp was untiring in her efforts to keep up the courage and resolution of her companions. When at midnight on the 4th of September, the sun for the first time left the sky she got up a party to celebrate that luminary’s departure Accompanied by Alain and Hubert, she climbed one of the peaks near Cape Ritter and remained with her eyes fixed on the southwest. Fortunately the temperature was supportable, the sky being wonderfully clear. The sun had reached the fringe of bare hills on the flanks of Mount Petermann, 10,000 feet high. For a moment it seemed to rest on the ice of Mount Payer, the giant’s neighbour and inferior by nearly a third. Then he descended, his disk grew larger, he lost his brightness, and red as blood, he hung like a glory behind the mountain’s peak. Larger and wider he grew until he slipped from sight, fallen to the other side of the earth. This was the beginning of the night. From that day the light decreased with sinister rapidity. But the darkness came not too suddenly for a welcome. The last works had been finished round the house. A rampart of ice, or rather a wall of thick ice-blocks that the cold would bind closer, was raised two feet above the walls of wood. It was carried right up to the roof in order that the slight humidity from the gutters might help to cement it. The space between the walls was filled up with saw-dust and straw, and on this, in the future, all the cinders from the fires would be thrown. The courage and good-will of the explorers were rendered the more effective by their own experiences, the ideas that occurred to them, and the information derived from preceding expeditions. The time for preliminary investigations had come, and the travellers knew from the counts of their predecessors how dangerous were these autumn campaigns. The first thing to do concerning them was to decide on the plan to be followed.