CHAPTER II

FORT ESPERANCE.

ON the 15th of May the Polar Star rounded the North Cape. Up to then the plan that had been agreed upon was to sail north-east. They wished, in fact, to follow in the route of the Tegetthoff expedition commanded in 1872-1874 by Payer and Weyprecht, who from Nova Zembla, situated in 76° north latitude, had reached an unknown coast they had called Franz Josef Land, and which they supposed extended from the eightieth to the eighty-third parallel.

This plan, besides enabling the travellers to be near the old continent, had also the merit of flattering the vanity of those desirous of opening up an entirely new road. “It will be very unfortunate,” thought De Keralio, “if we cannot manage to find a passage beyond longitude 30, between Spitzbergen and the fragmentary lands of Nova Zembla.”

Captain Lacrosse had steadily objected to this plan, and the reasons he had invoked for combating it were weighty. Besides going at a venture, they were in a peculiarly conceited spirit, neglecting to avail themselves of the experience of their predecessors, notably the precise discoveries made in Grinnell Land in 1875 and 1876 by Nares, Markham, and Stephenson, and more recently in 1881 to 1884 by Greely, Lockwood, and their gallant and unfortunate companions.

Lacrosse reasoned with sound common sense, “At least,” he said, “by going that road we shall have an open course up to the 83rd parallel. Smith Sound and Strait, Lady Franklin Bay, are nowadays well known as rendezvous for people who know what they are about.” He added, not without some appearance of truth,— “It is to be feared that the breaking up of the ice will make the road very difficult in a region where there is. little land, and it may carry us to the westward, in spite of all we can do. That will be so much lost time, as we should have to winter in the neighbourhood of Iceland, and thus exhaust a third of our provisions on the voyage alone.”

His opinion was only too soon to be confirmed by facts.

On the 16th of May it could be seen that the field of ice was so little broken that it afforded no passage to the Polar Star, The numerous attempts that were made ended only in a loss of time, and notwithstanding all they could do, they had on the 25th of May drifted four degrees to the westward. The way that was blocked in the east seemed in curious irony to open out to the west.

De Keralio’s obstinacy gave way before this demonstration of the facts themselves, and, yielding to the captain’s advice, he was the first to decide in favour of a change of direction.

To the general satisfaction the north-easterly route was abandoned in favour of the one towards the opposite horizon, and the Polar Star steered for the southern end of Spitzbergen.

The sea gradually becoming clearer of ice, this point was reached on the eighth of June. On that date eighty days had elapsed since their departure from Cherbourg. They were in the 78th degree of north latitude. Five only remained for them to traverse to reach the extreme limit of human investigations. But all knew that a veritable campaign was about to begin, rich in struggle and effort. To travel three of these degrees in sledges, Nares, Markham, Stephenson, and then Greely, Lockwood, and Brainard had taken two mortal years.

They must hasten. The Arctic summer is very short, and when July was over the cold would begin again. Since passing the Polar circle they had no need of artificial light; the midnight sun had been their luminary. For nearly a month the broken ice had only been met with in inconsiderable fragments. But the captain had only shaken his head and smiled at Isabelle’s exclamation of astonishment. “Patience! All this will change. Do not forget we are in the least encumbered part of the polar seas. We can only depend on getting a start from Greenland.” He told her true. It was in vain that from the southern extremity of Spitzbergen they tried to steer straight for the north. The pack or field of ice stopped the Polar Star on the second day. It was even impossible to keep to the westward along the 78th parallel owing to the drift ice. The drift continued for three degrees. Then the field of ice under the action of a warm current opened again. Captain Lacrosse steered obliquely towards the northwest. On the 25th of June they had regained the 77th degree, and the coast of Greenland appeared, bordered by an icy barrier about thirty-five miles long. Obliged to keep a careful look-out on her surroundings, the Polar Star steamed hardly eight knots an hour. As the ship went further to the north the ice became more frequent. Now they could follow it without interruption as a string of islands of unequal size. At present the blocks were all flat on the surface, being fragments of the ice field. But they were becoming more uneven, more hummocky, bristling with sharp points, striped with longitudinal cracks, with clear brilliant crevasses like the edges of broken glass. Behind them others appeared, higher, larger, which took the strangest of forms. Some looked like distant sails on the horizon, and the flotilla increased in numbers as they approached the grand fiord of Franz Josef discovered by Payer during the voyage of the Germania and the Hansa. At last on the 30th of June the Polar Star entered the fiord and cast anchor under the same 76th parallel they had already reached on the coast of Spitzbergen. The moment had come for putting into execution the second part of De Keralio’s plan. This consisted in landing a party, and then returning as quickly as possible to the south for dogs and Eskimo drivers, indispensable for the coming sledge journeys.

The plan had suffered from such modifications that it might be said to be an entirely new one. Precious time had been lost in their attempt by way of the east. Instead of going north from Franz Josef Land, they were on the east coast of Greenland below Mount Petermann. It was proposed to take an oblique course from the 24th to the 5Sth degree of east longitude, so as to cross if possible Lockwood’s route in 1882, at about 82° 44' north latitude. It was a grand scheme, bristling with difficulty; but, as De Keralio said, was that an obstacle to stop a Frenchman?

Captain Lacrosse had forty-six days, from the 1st of July to the i5th of August, in which to reach the south of Greenland, double, if necessary, Cape Farewell, and return to Franz Josef fiord with the dogs required by the expedition.

Fortunately, this was the warmest period of the year. The Polar Star during her three months’ voyage had experienced no storm. She was still abundantly provided with coal, and even after her return would have enough for a further dash towards the north if the sea opened before her adventurous commander.

Thanks to the measures taken a long time in advance, and minutely calculated, the landing of the chief explorers was accomplished in a day. The crystalline border of the fiord was only six miles wide, and such were still the solidity and thickness of the ice that there was no fear of its breaking up. These borders along the shore have remained unthawed for centuries, and their bases apparently rest on the rock itself, forming a ledge from six to nine feet thick above the level of the open water.

To assure himself of safety, Lacrosse began by taking soundings, and found twenty-five fathoms down a bottom of syenite and schistose rocks. It was evident that there was a gentle slope up to the land.

When the travellers landed they took with them certain numbered pieces of wood for the rapid construction of a hut in which they could take shelter. Here, again, frequent drill in piecing together and taking apart the beams and scantling, walls and partitions, of the wooden house, resulted in a truly wonderful economy of time. The exceptional mildness of the temperature— reaching nine degrees centigrade between noon and three in the afternoon, and dropping only to five between midnight and three in the morning—favoured the work. In six hours, Fort Esperance, such was it named, was fit to receive the twelve persons who came ashore, that is to say, De Keralio, his daughter Isabelle, his nephew Hubert, the good Tina Le Floc’h, Isabelle’s nurse and servant, Dr. Servan, the naturalist Schnecker, and six Breton sailors, Guerbraz, Helouin, Kermaidic, Carions, Le Maout and Riez. It was to these twelve that the rest of the crew left the task of completing the two wings necessary for the ultimate reception of the thirty-three officers and men remaining on board the ship, and who would return from their run to Cape Farewell to shut themselves up with their companions for the long winter night.

The dog Salvador followed Isabelle ashore. He could not live away from his young and valorous mistress. On the 1st of July in the morning, Captain Lacrosse, after a farewell banquet given on board the Polar Star, shook hands with those who had landed on the Green Land of the north, and gave the signal of departure, promising to return before the month of August.

There was a moment of indescribable sadness when the steamer began to move under the first impulse of her screws. Whatever might be the ardour of the intrepid explorers, they were unable to face this first separation without apprehension. Those who remained were to have their first experience of sojourning on a desolate land; those who went were to find a land almost as desolate, and enter Into communication with a most rudimentary people.

Rut they were sure to come back again. And so the oppression at this preliminary separation was soon overcome and those who were left behind set to work to make the most of the time that remained before the coming of winter.

The first thing was to get the house into order. The house was quite a masterpiece of practical and hygienic arrangement. It measured as it stood, without the wings that were to flank it, forty feet along the chord of the semicircle in which it was built. The diameter of its wino-s would add six feet more at each extremity. It would thus be in a circular form, the second half overlapping the first, with an interior courtyard twenty feet across covered with a movable roof.

This curious edifice, which was not unlike a panorama, contained a number of rooms, or, more correctly speaking, compartments. One of these rooms, the best furnished, was reserved for Isabelle and her nurse. Besides the two dining-rooms of unequal size, one for the officers, the other for the crew, the house contained the kitchen, three bath-rooms, a physical and chemical laboratory, an astronomical and meteorological laboratory, an infirmary, a dispensary, and altogether ten public rooms and eight private apartments.

It had been designed by De Keralio, and the plans had taken a year to prepare and improve with the help of Doctor Servan.

It was consequently with very natural pride that De Keralio did the honours to his companions who had now become his guests in this provisional habitation that in more favoured regions might have been a permanent one. And it was with considerable satisfaction that he explained its many advantages.

“Consider that our house is built of sections carefully numbered, and therefore as easily taken to pieces and carried away as they have been put together here. We have a double wall of planks, and the inner wall is covered with the waterproof sheeting which keeps in the warm air. The walls are ten inches apart and form an air chamber. Their inner surfaces are covered with paper, and for greater security we are going to cover the partitions with woollen curtains.”

And omitting no detail, he showed his wondering visitors the columns of copper and steel sustaining the light wooden framework and the gentle give and take of the timbers so as to allow for the most violent winds by the play of the angles at the bolts; the storeroom towering over all, the roof with the skylights to make the most of the light of day, and at the same time minimize the inevitable currents of air from doors and windows, the felted floor supported by the beams of iron covered with wood. A circular corridor, or rather a gallery, put all the rooms in communication and allowed of passing from one to the other without going outside.

As they were going through the house which had been built and furnished in less than forty-eight hours, the chemist Schnecker, who had been examining everything with the greatest attention, suddenly exclaimed in surprise,—

“Ah, my dear sir, there is something which might have been thought of.”

“What is that?” asked De Keralio.

“How about the fire-places? They are not only not designed to give enough heat, but where are you going to get the gas for them?”

Before De Keralio could reply, Hubert struck in.

“Sir,” said he with a laugh, “please to remember that if we wish to produce gas in the ordinary sense of the word, that is to say, bicarburetted hydrogen, the thing would not be impossible, for there ought not to be any want of coal seams in the neighbourhood. Nares and Greely found them ready to hand at Port Discovery on the coast of Grinnell Land. But you may say it would be easier for us to burn the coal itself, and you will see that this reply has been foreseen, and that the fire-places are designed to serve more purposes than one.”

And so saying, Hubert took hold of a sort of handle at the side of one of the fire-places, and turned the receptacle completely over; the sheet of shining copper at the bottom disappeared and gave place to a regular grate for coke or coals.

Schnecker opened his big eyes.

“That is a good fire-place, certainly; but all the same, I am surprised that the gas-burning arrangement is there, if there is to be no use for it.”

”I did not say that,” said Hubert.

“Then I do not understand. Where are your pipes and your gasometers, your condensers and your retorts? Where are you going to get the heat necessary for the distillation of the carburet?”

“Bah!” replied the young man, “we will find it. And allow me to be surprised in my turn that a chemist like you should require to use such cumbrous apparatus, which would be quite useless for travellers as we are.”

“Useless!” exclaimed the Alsacian. “Would you have me believe that you can get heat without employing the usual methods of modern industry?”

D’Ermont put his hand on his questioner’s arm.

“I do not try to make you believe it, but to show it you quite simply. There is gas and gas. I have only to get a source of heat ten times, twenty times, a hundred times superior to those of modern industry to realize the miracle you would deny.”

The chemist shook his head.

“ I do not deny it—I doubt it. That is another thing.”

And as he said it, he frowned, and gave the lieutenant an evil look from the corner of his eye.

Isabelle noticed this look, but made no sign of the impression it had on her, contenting herself with keeping a more careful watch on this suspicious companion. At the same time, she remembered that on the Polar Star, Hubert had knitted his brows at Schnecker’s name, and in some way communicated his dislike of the chemist to the faithful Salvator.

“Scientific rivalry,” she said, “that is all it is between them.”

And as Isabelle was the most trusting, the most generous of girls she did not allow her thoughts to dwell longer on the second incident than she had on the first.

They were soon to recognize the advantages of the house scientifically constructed by De Keralio and Doctor c pi-van. Owing to the absence of trees, the concluding period of the polar summer was, in these latitudes, remarkably warm. The temperature reached sixteen degrees centigrade, and proved almost insupportable to the travellers, who feared it might rise higher. These days of inaction were devoted to hunting and fishing, and in both Isabelle took her share. It was the only recreation possible, and it was desirable to add to the stock of provisions. The duration of their stay in these desolate lands could not be foreseen, and it was as well to lay in a large quantity of fresh victuals. There was abundance of game, chiefly feathered .game. Guerbraz, the best shot of the party, killed, during one morning, two dozen eider ducks. They knocked over in scores, or took in the nets, ptarmigan or polar partridges, black-throated divers, dovekies, a kind of pigeon or rather gull, with oily but succulent flesh.

During the morning of the fifth day after they had taken up their quarters at Fort Esperance, Guerbraz ran into the station out of breath, and answered in gasps to Hubert’s eager questions,—

“Cattle! Two miles to the north.” Isabelle heard him.

“Cattle!” she exclaimed. “Musk oxen! I am after them!”

For some days now, the girl had been in her shootinp dress. It became her wonderfully, and one could not wish more elegance and grace in a woman in a semi-masculine costume. She wore warm woollen knickerbockers gathered at the knees into leather gaiters, over which fell a short petticoat like that worn by vivandieres. A vest with a broad belt clothed her from waist to neck, and on her charming head was a cap of sable, fitted with ear flaps and a neck piece. A carbine, a masterpiece of precision as of artistic ornamentation, hung from her right shoulder, while from her left hung her bag and cartridge-belt.

Thus equipped, Isabelle hurried out after Hubert and Guerbraz.

As they came out of the house, they met the chemist, Schnecker.

“Where are you running to, like that?” asked the Alsacian.

Hubert replied as laconically as Guerbraz,—

“ Cattle! If you want to come, look sharp.”

The scientist wanted no repetition of the advice. He also rushed into the house to get his gun.

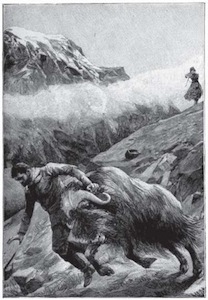

But already Hubert, Isabelle, and Guerbraz were scaling the lower hills, and, hiding behind the heaps of rocks, were approaching the musk oxen as quickly as possible. They were not very numerous, and consisted of a bull, two cows, and two calves. The five beasts were placidly pasturing on the scanty herbage, and showed no alarm at the threatened attack on them.

Suddenly the two hunters and their companion arrived within range and three reports echoed simultaneously. Two of the cows and one of the calves were seen to fall; the bull was also shot, but rose and made off, leaving a trail of blood behind him.

This did not suit Guerbraz, who had hit him in the haunch. Without thinking of the danger, the Breton rushed at full speed after the ox and contrived to cut off his retreat.

Then the scene changed suddenly, and became extremely dramatic.

Guerbraz, an old fisherman of Iceland and Newfoundland and an old Arctic voyager, was endowed with prodigious strength. Already he had taken from his belt a short-handled axe with which he intended to strike the animal on the neck a little lower than the formidable cap made by the large horns, when the bull, renouncing flight, made straight for his assailant, and returned towards him at his fastest.

Guerbraz, carried away by his own eagerness, and, unable to stop on the sloping ground, could not get out of the way. The furious beast met him as he came down the slope. Luckily the shock was not a direct one, but was only a touch on the shoulder, which sent him rolling on the rocky ground.

But the bull, after passing the sailor some thirty yards, pulled up and returned to stamp on him, or to butt him with his horns. Guerbraz, stunned by his fall, could not get out of the way.

Suddenly there was another report and the ovibos fell dead at the sailor’s feet.

Isabelle ran up, her gun smoking; Guerbraz seized her hand and kissed it piously.

“You have saved my life, mademoiselle,” he exclaimed. “I must have my revenge. A life for a life.”

Isabelle could hardly speak for want of breath. And besides, the incident was followed by another as a pendant.

There was a fifth report, and Hubert, who was just reaching his companions, felt the wind of a bullet at less than a foot from his face. Turning quickly, he discovered Schnecker about sixty yards behind. He it was who had just fired.

“You are a bad ,shot, sir!” exclaimed the lieutenant, in a tone in which anger and contemptuous irony were only too apparent.