“Honorverse Analytics: Why Manticore Won the War” by Pat Doyle and Chris Weuve

Pat and Chris are members David Weber’s Honorverse consulting group, BuNine. Both are defense professionals who use their day-job expertise to help David flesh out the background worlds and ways of the Honor Harrington series novels. The analysis below is an example of the sorts of briefs and articles BuNine prepares for David as he continues his imaginative journey exploring the Honorverse and bringing his stories to millions of readers.

The War Manticore Shouldn’t Have Won

The war between Haven and Manticore in David Weber's Honorverse series is, on the surface, a David-versus-Goliath matchup. The People’s Republic of Haven consisted of some three hundred star systems and was, by any reasonable measure, the dominant force in its section of the galaxy. Manticore, on the other hand, started the war confined to two star systems, with only a handful of additional systems aligning with it to stand up to the Peeps. It seems as if this should be an easy Haven victory.

Like any good (fictional) David and Goliath matchup, though, the question isn't whether David wins, it's how and why. The authors (both graduates of the U.S. Naval War College) will attempt to shed light on that question by applying some of the analytic concepts learned in our professional study to the Haven-Manticore war.

To answer the how and the why of Manticore's victory, we will first recap the situation in which the combatants find themselves at the beginning of the war, and then we will look at the situation through the lens of two important concepts defense professionals use in their analyses: "Center of Gravity" and "Elements of National Power."

Two quick notes up front: First, in this essay we will ignore the Mesan Alignment and the developing conflict with the Solarian League. As any Spiderman fan knows, with great power comes great responsibility, and in this case responsibility includes neither giving up spoilers nor nailing David Weber's feet to the floor by answering questions which should not get public responses yet.

Second, over the course of the twenty-plus years covered by the main Honorverse books, a lot happens. The People's Republic of Haven becomes the Republic of Haven, the Star Kingdom of Manticore becomes the Star Empire of Manticore, and the Manticore-led Alliance grows, then splinters a bit (even if it does not actually fail) before rallying. The war itself was fought in two very different phases separated by a ceasefire. These changes, while important to the story, do not affect a strategic analysis of the situation. In this essay, therefore, we will use "Haven" to refer to the (People's) Republic of Haven in all of its incarnations, and "Manticore" to refer to the growing Manticore-led alliance encompassing both the Star Kingdom and the Star Empire.

The Interstellar Situation at the Beginning of the War

Before we jump into an examination of Center of Gravity and the Elements of National Power, it's worth a brief refresher in some of the salient characteristics of this universe, in other words, how this universe works. This can be broken down into three areas:

1) The physical, astrographic description of the situation;

2) the salient characteristics of communication of this universe; and

3) a brief look at the combatants themselves.

Astrography

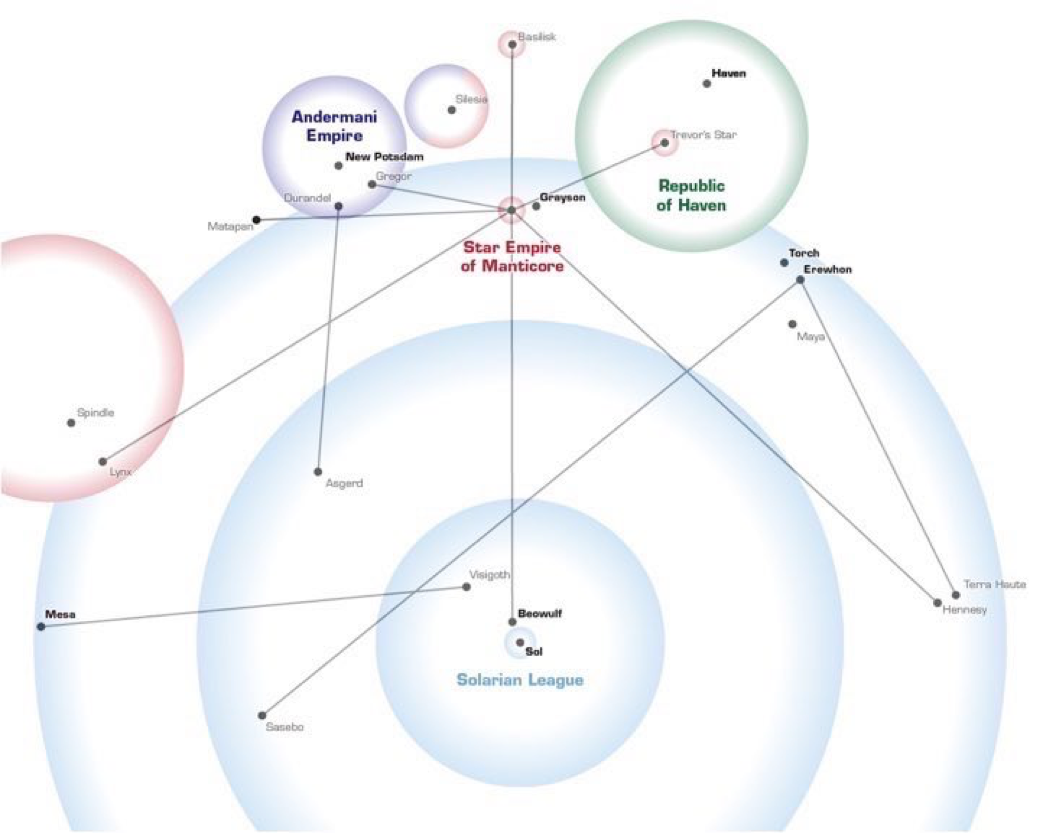

The first salient feature of the Honorverse at the beginning of the war is astrography. Looking at the map below, a couple of things jump out. First, Manticore is small. Starting the war with just the Manticore binary system (with three inhabited planets) and the Basilisk system, Manticore is surrounded by larger neighbors. Grayson, Erewhon, and other allies add but a handful of systems. Haven, on the other hand, is huge—the second largest political entity in human space, with the second largest military.

Illustration 1, used by permission of the authors.

The size disparity between the two star nations goes beyond just resources. It also effects what is known as strategic depth, which is usually viewed as the ability to trade space for time. Think for a moment about the disparity between Israel (a country with no strategic depth) and Russia (a country with a lot of strategic depth, as Napoleon and Hitler discovered). At the beginning of the war Manticore has virtually no strategic depth, as the vast majority of both its population and its economic wherewithal is concentrated in the Manticore home system. Haven, on the other hand, has lots of strategic depth—it can and does lose star systems over the course of the war with little decrease in its own warfighting capability. Worth noting, though, is that strategic depth is a more nebulous concept in the Honorverse than in our own universe. Even leaving aside the hyperbridges, the nature of hyperspace travel in the Honorverse has the effect of making space non-contiguous, by which we mean that you can get from point A to point C without going through point B. In theory, then, the Royal Manticoran Navy could appear above Nouveau Paris without warning, just as a Havenite Fleet could do the same at Manticore.

While there is nothing physically preventing such an attack, there are practical considerations. First, targets of value are likely to have defenses, and rash concentrations of force to take out defenses would create weaknesses for the other side to exploit. We see this discussion time and again in the series—Manticore maintains a large homefleet to protect the home system, and generally resists the temptation to deploy those ships elsewhere. Second, while space is non-contiguous, it is does embody time and distance. A force might bypass nearer systems and strike deep at the enemy's heart, but it will spend months doing so, with refit and resupply consequently being further months away. The war was fought along moving fronts not because the fronts could not be bypassed (they often were), but because refit and resupply requires bases close to the action, which in turn limits the effective radius of fleet action. Finally, while Manticore lacked strategic depth, Admiral Caparelli and his senior commanders (Jim Webster, Hamish Alexander, and later Honor Harrington herself, among others) were well aware of the danger and worked hard to make sure Haven never got the chance to strike a knockout blow, or at least that the Havenite leadership would never be so confident of success that it was willing to risk the outcome of the war on one throw of the dice. When desperation then forced Haven to make that throw anyway, the carnage—and the outcome—ably demonstrated why such a tactic was considered a desperate measure.

Second, Manticore is connected. Thanks to the Manticore Wormhole Junction, Manticore has direct or indirect lines into the Solarian League, the People's Republic of Haven, the Silesian Confederacy, the Andermani Empire, and, later, the Talbot quadrant. Manticore thus enjoys robust trade possibilities (including user fees for foreign hulls wishing to transit the Manticore Wormhole Junction) as well as interior lines of communication. The Manticore Wormhole Junction is a force multiplier, allowing the Royal Manticoran Navy to be efficient with its deployments and to respond rapidly to attack. As we shall see, this is a source of great strength—and potentially fatal weakness.

Third, Manticore potentially has other worries. The Andermani Empire, while smaller than Haven, is much larger than Manticore, and has something of an opportunistic (if not outright predatory) reputation itself. And while the Silesian Confederacy isn't much of a military threat to Manticore, its proximity and anarchic state makes it a military sump, drawing off resources Manticore can ill-afford to lose.

Communication

The second salient feature of the pre-war Honorverse is the nature of communication and the movement of information. In our modern world, information movement is near instantaneous. Long-distance communication via satellite and fiber optic cables is usually fast and trivial, and we benefit from a variety of resources which make it possible to gather information across global distances in near real time.

Not so in the Honorverse, where communication between star systems is limited to the speed of the fastest ship. News, orders, personnel, cargo—all travel via spacecraft, at roughly the same rate. The one significant exception to this are hyperbridges like the Manticore Wormhole Junction, which "shortcut" hyperspace and allow much faster travel. (This does not include the Manticoran FTL comms, of course, but those are limited to intrasystem usage.)

Overall, then, from a communication standpoint the Honorverse is a lot more analogous to the mid-19th century than our current time. In the 19th century, telegraphs allowed for rapid communication on land, somewhat akin to the FTL comm, but long-range communications with other continents required ships. National leaders would send their navies to sea, without the ability to collect information once they were gone. This is much more akin to the Honorverse than our present days of long-range radio, transoceanic cables, and spy satellites.

The Combatants

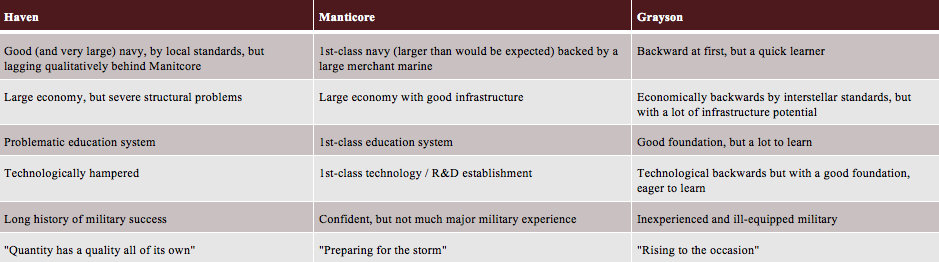

The table below is a quick summary of some of the characteristics of the three major combatants—Haven, Manticore, and Graysoni—at the start of the war. It describes three very different star nations:

- Haven: The 800 pound gorilla, with a history of success hiding some severe structural problems

- Manticore: Small, but feisty, wealthy, extremely competent, and diligent in its preparations for the coming war

- Grayson: Backwards now, but with lots of potential

Illustration 2, used by permission of the authors.

Two things are worth noting about the above table. First, it does not actually capture the effect of the Manticore Wormhole Junction, except indirectly. The Junction is a topic we'll discuss in some detail below. Second, the rows in the above table are not independent of each other. Manticore's large economy, for instance, facilitates a large well-equipped navy, a first-class educational system, and a robust research and development program. Likewise, Haven's problematic educational system serves to hinder both its technological prowess and the quality of its navy. Grayson arguably has a lot of infrastructure potential precisely because it is technologically backwards; its manpower-intensive brute-force approach at the beginning of the series means there is a lot of potential to be tapped once Manticoran efficiencies are adopted. And, of course, Grayson has a couple of technological tricks of her own to share.

Analysis of the Problem

Analyzing military operations is an art, not a science, and the exact tools used require a little practice. It's the basis of an entire masters degree program at the Naval War College, for example, with operational art being the subject of its own class of full-time study for a couple of months. In this example we are leaving out a lot of the standard analysis; what we are doing, therefore, should be viewed as an introduction to the topic and not the last word. (Thankfully, real lives are not at risk in this example.)

Center of Gravity

The first concept we will look at is called center of gravity. A combatant's center of gravity (COG) can be defined as "The source of power that provides moral or physical strength, freedom of action, or will to act. See also decisive point."ii The same source defines "decisive point" as "A geographic place, specific key event, critical factor, or function that, when acted upon, allows commanders to gain a marked advantage over an adversary or contribute materially to achieving success." Not all decisive points are COGs, but all COGs are decisive points.

Determining the center of gravity for both oneself and one's opponent is one of the most important considerations of a strategist. As a primary source of an opponent's strength, his COG is potentially an important target. COGs are not strictly an Achilles heel; a COG is not necessarily a vulnerability. Strictly speaking, it's not necessary to attack an opponent's center of gravity to defeat that opponent, but it is often the most direct path to achieving that goal. The enemy is, of course, thinking the same thing about you. The center of gravity might change over time, so the process of analyzing the COG—like that for all strengths and weaknesses—should be continuous.

Manticore is a good example of why a combatant's center of gravity is sometimes not immediately obvious. There are really only two possible candidates for the Manticoran COG: the Manticore home system itself, and the Manticore Wormhole Junction. Both are critical to the war effort, with the home system encompassing the bulk of Manticoran production and technological expertise, and the junction providing strategic communication and mobility to the military, as well as being a substantial source of revenue.

There is a better case, though, for the Manticore Wormhole Junction as the center of gravity for Manticore. Most of Manticore's strategic advantages come directly or indirectly from control of the Manticore Wormhole Junction. You could imagine Manticore building its infrastructure elsewhere (Basilisk, or now Talbot), and still being able to compete with Haven in the war. It's hard to imagine Manticore being competitive with Haven without the junction.

Determining the COG for Haven is more difficult. There are more competing options and, unlike Manticore, many of them are not tied to specific places. With Manticore the difficulty came from deciding between two strong candidates; with Haven the problem is a plethora of lesser candidate COGs. This illustrates another attribute about COGs: sometimes they can be quite ill-defined. Possible candidates include:

- The capital, Nouveau Paris

- The regime itself

- The PRH/ROH Navy

- Haven's sheer size

In the end, the best candidate for the Havenite center of gravity is the sheer size of the star nation. Historically Haven steamrollered its opponents, as it tried to do to Manticore. As a straight-up fight between equal-sized entities, the Haven-Manticore war would have ended sometime in book two, and David Weber would now be working on the twentieth book in his Apocalypse Troll series.

This is not, to say, however, that the other factors are unimportant. The PRH put a real emphasis on regime survival, against both internal and external enemies, and Nouveau Paris itself was both an important symbol of the regime and the place where an uprising or coup could result in the leadership being strangled in their own beds. (Okay, Oscar Saint-Just wasn't exactly strangled.) The Havenite Navy in particular could be viewed as the Havenite center of gravity. You can imagine Haven building the large navy necessary to engage in the war by drawing upon an empire of its size, but it's hard to imagine it having a navy of that size without the empire coming first.

Elements of National Power

Another important concept worth considering when analyzing how and why Manticore won the war is that of the Elements of National Power. These elements describe the tools that a nation has at its disposal in achieving its strategic objectives vis-a-vis foreign powers. In American usage this is usually abbreviated as DIME, for Diplomatic, Informational, Military, and Economic. Of course, like all acronyms, there has been a tendency to add to the list over time, but for our purposes DIME is sufficient. Like many things in life, the lines between these elements often blur, and specific activities may fulfill multiple objectives at the same time.iii

The Diplomatic element covers all of the activities designed to achieve strategic goals through the use of political interactions at the governmental level. This can include treaties, alliances, coalitions (less formal and encompassing than alliances), and lesser diplomatic activities. Diplomacy has sometimes been characterized as saying "nice doggy" while looking for a rock, which only covers part of it.

Before and during the war, Manticore employed a multi-pronged diplomatic effort. Manticore sought allies in its local neighborhood while attempting to convince the Solarian League (and the Andermani Empire) to at least maintain neutrality in the conflict. It worked hard to build an alliance structure; the process of doing so involved not only diplomats but military-to-military contacts.

Haven's diplomacy was, by and large, more ham-fisted. Haven was more inclined to use covert action than diplomacy.

The Informational element of national power is in many ways the least well defined. It includes deception activities, strategic communications (basically, getting your message out, and rebutting your opponents), intelligence activities, and the like. The target can be the enemy military or the leadership, the enemy's population or your own. Oftentimes it overlaps with military and diplomatic activities.

Manticoran information activities during the war include the excellent work of the Office of Naval Intelligence, the diplomatic efforts of Admiral Webster and other efforts in the Solarian League to engage Solarian media outlets and highlight the abuses of the current Havenite regime, and the interaction of the Manticoran government with its own press. These policies both engendered support for the war at home and benefited Manticore abroad. Haven's efforts, on the other hand, consisted mostly of internal propaganda efforts, often focused on support for the regime as much as support for the war. (You do not need political officers if your concern is simply the war.)

The Military element of national power is much more obvious, and we will largely skip it, as it's well covered in the novels and fairly straightforward. We will note, though, that the logistics, training, and supporting infrastructure is often as important as number and classes of starships.

One point about the military element should be emphasized, though, even though it is mentioned in the novels: Manticore has the military wherewithal it does because King Roger Winton III saw the war coming decades before it actually broke out and made winning the war a priority. He worked hard to instill a warfighting culture in his military, and he leveraged the economic benefits of his star nation to establish the long-term military research program that began really paying off in the final years before the war started. King Roger understood both that this war would be different (see the forthcoming House of Lies for more discussion of this), and that the Star Kingdom's military element of national power was inadequate to the task expected of it—and he took the steps necessary to correct the deficiencies. More than any other single person, King Roger was responsible for Manticore's victory, despite being in the grave for four decades at the time of the war's conclusion.

The Economic element involves resources and the use thereof. This includes ongoing budgets, access to raw materials, physical infrastructure, and a host of other activities involved when the government says "build, equip and man a ship." Manticore and Haven were both economic powerhouses, with one important difference. Haven achieved its economic status through aggregation of hundreds of star systems, some of very low productivity. Its per capita production capability was relatively low. Manticore, on the other hand, had a relatively small but extremely productive population. This meant that Haven had to always use the vast majority of its economic production to satisfy internal needs, whereas Manticore could devote a lot higher percentage of its resources to the war.

Summary

Weaving the above threads together, then, Manticore's victory over Haven can be summarized as follows:

1) Manticore was able to successfully use its center of gravity, the Manticore Wormhole Junction, in a myriad of ways. These include as a source of revenue, a method of communication, and as a force multiplier for the navy. It provided Manticore with interior lines, enabling it to optimize the redeployment, refit, and resupply of its forces, and to respond to crises in a timely manner. Haven, in contrast, had no such boon, and had to do everything the hard way.

2) On the diplomatic front, Manticore was able to build an effective alliance structure through the use of technological and economic incentives, and by effectively making the case that they and other local powers needed to "hang together lest they hang separately." With regard to the Andermani Empire, Manticore was initially able to convince New Potsdam to remain neutral, and was eventually able to convince them to look favorably upon the cause. Haven had no comparable diplomatic effort, although in fairness they did not really need one.

3) On the informational front, Manticore successfully used the variety of tools lumped under the term "informational" to their advantage. The Office of Naval Intelligence proved itself to be one of the galaxy's best intelligence services (behind only the Andermani). Manticore's information campaign in the Solarian League neutralized Havenite advantages (largely based on an out-of-date reputation) and on occasion moved Haven to the defensive by promulgating the human rights offenses of the new regime. Domestically, Manticore kept its population informed and behind the war effort. Haven's interstellar efforts, by contrast, were largely limited to damage control and its domestic efforts to controlling access to information.

4) On the military front, Manticore successfully leveraged its economic and technological advantages (the latter the result of specific preparations made for the coming war) to provide a navy without peer. Coupled with the aforementioned interior lines provided by the Manticore Wormhole Junction, Manticore was able to punch FAR above its putative weight class. Pound-for-pound the Royal Manticoran Navy was without equal anywhere in the galaxy, and even the resurgent Havenites or the Andermani would need a greater than two-to-one advantage to best the RMN. The Republic of Haven Navy was no slouch itself, eventually developing into the second most powerful star navy.

5) On the economic front, the salient features of the Manticoran economy which differentiated it from the Havenite economy—high productivity, a highly skilled workforce, a large merchant marine, and a steady income stream from Manticore Wormhole Junction transit fees—allowed Manticore to use its economic might much better than Haven could use the Havenite economy. The great irony of the situation, of course, was that these features were exactly what made Manticore such an attractive target to begin with.

Conclusion

As mentioned in the beginning, in fiction a David-versus-Goliath matchup usually results in a victory for David, because otherwise a David-versus-Goliath matchup would be pretty boring. One element that makes the Honorverse interesting to the authors is not the outcome per se, but how we get there—not the destination, but the journey. In this case, it has given us the opportunity to practice our craft, put our lessons to work, and hopefully share a few things you might find interesting.

Footnotes:

i. Excluding Grayson at this point was more confusing than including it.

ii. Joint Publication 1-02 Department of Defense Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, 8 November 2010 (As Amended Through 15 February 2016)

iii. DIME should not be confused with PMESII (Political, Military, Economic, Social, Infrastructure, and Information), which is a related concept designed to describe national attributes. DIME describes what you do; PMESII describes what you are.

Copyright © 2017 Pat Doyle and Chris Weuve

Pat Doyle is Chief Pilot, BuNine Flight Operations. In his other life, Pat is a commercial airline pilot, naval reservist, and wargame designer with a strong interest in military history, tactics and strategy. Pat's geek superpower is starship combat. He is a four-time national champion for a popular starship combat game and has published the Tactics Manual for that game. His contributions to the Honorverse are in helping to define the operational level of war and he is working to design a fleet starship combat game within the Honorverse. Pat is a graduate of the Naval War College short course.

Christopher Weuve is a founding member of BuNine. In his other life, Chris is a naval analyst working for the Department of Defense. He spent six years at the Center for Naval Analyses as a naval exercise analyst and wargame designer, and five years on the faculty of the Naval War College as a wargame designer and analyst. Chris is a founding member of BuNine (David Weber's Honorverse analytic visualization team), and was an editor for House of Steel: The Honorverse Companion, in which he also coauthored (with David Weber) the "Building a Navy in the Honorverse" chapter. As both an avid science fiction fan since before he was old enough to read and a Distinguished Graduate of the Naval War College, Chris spends his free time analyzing Real-World ™ naval warfare and how similar subjects are represented in science fiction. He is (to the best of his knowledge) the only person ever interviewed (twice!) by the journal Foreign Policy about science fiction warships.