by Terry Burlison

On the morning of Feb. 1, 2003, the world watched in horror as the space shuttle Columbia disintegrated re-entering Earth's atmosphere. Over the ensuing months, investigators pored over NASA's management practices, engineering decisions, and launch footage to determine the cause of the tragedy. Eventually the investigations ended, the families began the process of healing, and the names Rick Husband, Willie McCool, David Brown, Kalpana Chawla, Michael Anderson, Laurel Clark, and Ilan Ramon were engraved on the Astronaut Memorial Wall at Kennedy Space Center.

But few people remembered that the crew of STS-107 were not the first to lose their lives aboard Columbia.

“In his blood”

Rockwell technician Nicholas Mullon was a child of the space age.

Nick's father worked for Boeing at Cape Canaveral during the 60s, as NASA drove hard for the moon and “space fever” burned throughout eastern Florida. Young Nick grew up around astronauts, engineers, and other space workers, and dreamed of making his own contribution. After graduating Cocoa Beach High School, Mullon volunteered for the U.S. Army. Upon leaving the service in 1977, he followed his father's path, working on the new space shuttle program as a technician for Rockwell International. The space program was “in his blood,” according to Denise Mullon, who married Nick in 1975.

Mrs. Mullon describes Nick as “hard-working, loved by everybody, the kind of guy people gravitate to . . . and handsome as a movie star.” A man who enjoyed playing guitar and working with his hands, Nick began taking night classes in mechanical engineering while working as an aft fuselage wiring technician on the shuttle. Like thousands of others, Mullon worked tirelessly through long days and weekends toward the moment Columbia would roar into the heavens.

After nearly two years of delays, launch day finally approached. The morning of March 19, 1981, Mullon and his fellow workers stood watch at Launch Complex 39A, awaiting the conclusion of Columbia's final Countdown Demonstration Test (CDDT), the last major milestone before flight. After the test, they would enter and inspect the orbiter. Liftoff was less than a month away, and the future burned bright for the 25-year-old father of two.

Countdown

Launching a manned spacecraft is extraordinarily difficult, especially for the maiden flight of a vehicle as complex as the space shuttle.

During the launch countdown, the shuttle's huge external tank held millions of pounds of super-cooled liquid hydrogen and oxygen. As the count approached zero, thousands of pounds of those propellants poured through the orbiter's main engines. The engines then ignited and ran for a few seconds while the shuttle remained bolted to the pad. If any engine was not operating properly, the launch sequencing computer commanded a shutdown prior to liftoff, when the massive solid rocket boosters would ignite. In the case of such a launch abort, gaseous hydrogen and oxygen remained hovering around the pad, posing a fire risk to the shuttle and the launch complex. (On a later shuttle flight, that exact scenario resulted in a brief hydrogen fire on the pad.)

To mitigate the risk of gaseous hydrogen or oxygen seeping into access compartments inside the aft end of the orbiter, gaseous nitrogen (GN2), an inert gas, was pumped through those areas prior to the end of the countdown. During ascent, the nitrogen vented out of those unpressurized areas. If the launch was scrubbed, launch controllers purged the GN2 from the orbiter with breathable air so that workers could safely enter the compartments to inspect the vehicle.

In February, a month before the CDDT, the shuttle's three main engines were tested in a 20-second, full throttle burn while on the launch pad. The Flight Readiness Firing, or FRF, went perfectly and the GN2 purge was executed as planned. However, tests of the crew compartment atmosphere indicated a slight increase in nitrogen, leading officials to suspect a GN2 leak. Although the leak was not thought hazardous, test teams requested a deviation from the usual procedures for the March Countdown Demonstration Test to investigate. Even though the engines would not fire—indeed, the shuttle would not even be fueled—a longer GN2 purge would give engineers more time to assess the possibility of a leak.

Figure 1: Flight Readiness Firing (Official NASA photo, courtesy of the author)

Since nitrogen is inert and was not considered dangerous, certainly not when compared to other liquids and gases onboard Columbia, the change was not marked as hazardous. Ideally, safety committees reviewed all changes before being implemented, but for the CDDT over 500 deviations had been ordered. Only “hazardous” changes were reviewed.

Therefore, Deviation 13-20 was approved without full review and inserted into the countdown schedule. But due to a communications breakdown, the time now required to complete the longer purge did not get inserted into the integrated timeline. Test controllers in the Firing Room would be conducting the longer purge, but workers at the pad, operating off an inaccurate timeline, knew nothing of the extension. Since the change had not been properly reviewed, the discrepancy went unnoticed.

On March 19, as the countdown test neared completion, the extended GN2 purge began.

“Pad clear”

By 8:50 am, the CDDT had finished, astronauts John Young and Bob Crippen had left the orbiter, and the test director gave the pad clear announcement for workers to return to their tasks. Across Launch Complex 39A, contractors swarmed back to the shuttle. By now, the nitrogen purge would normally have ended and breathable air would be flowing into the shuttle. But under Deviation 13-20, GN2 still filled the aft compartments of the orbiter.

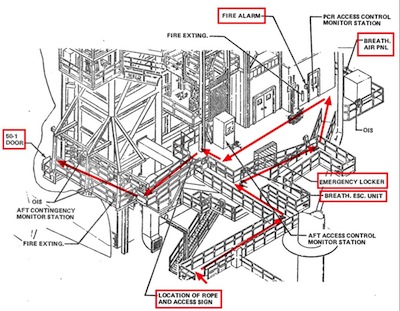

Shortly after 9 a.m., Nick Mullon headed for the launch pad to resume his duties in the shuttle’s aft compartment. A few minutes ahead of him, fellow Rockwell technicians John Bjornstad, Forrest Cole and William Wolford had already arrived at the pad and ascended the Rotating Service Structure (RSS), the massive steel framework that surrounded the shuttle and provided access for workers.

Figure 2: Rotating Service Structure, 130-foot level (Illustration from official accident report)

Red lines indicate path victims took to work station

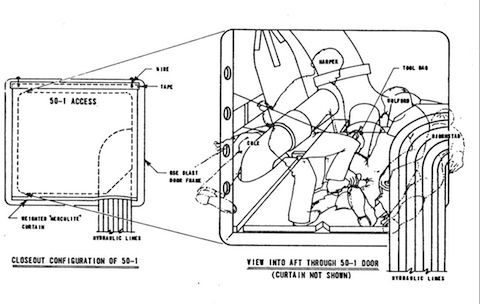

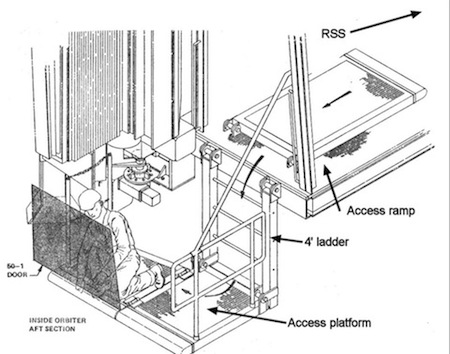

At 9:15 a.m., when they reached the 130-foot level of the RSS, Bjornstad, Cole and Wolford logged in, walked across the access ramp to the shuttle, then climbed down the four-foot ladder to the platform outside door 50-1 of the orbiter. Their task was to inspect and “close out” equipment in the back of the vehicle, near the main engines. The access door had been replaced by a curtain to provide easier access. According to their timeline the aft GN2 purge was complete, and the compartment was now filled with breathable air.

Bjornstad crawled past the curtain into Columbia and worked his way through the cramped quarters to his right; Cole followed, turning to his left and climbing deeper into the vehicle. The curtain fell shut behind them.

Nitrogen: “non-hazardous,” but deadly

Nearly 80 percent of the air we breathe is nitrogen, a virtually inert and usually harmless gas. Most of the rest is oxygen, which causes the release of carbon dioxide from our bloodstream into our lungs. This CO2 build-up triggers our sense of breathlessness, the need to inhale. But when breathing pure nitrogen, no CO2 is released into the lungs, and victims have no idea they are suffocating. They breathe normally until unconsciousness strikes.

And it strikes within seconds.

Twenty-two minutes of terror

Moments after Forrest Cole disappeared behind the curtain covering door 50-1, Bill Wolford followed. Crawling through the entrance, he turned to find Bjornstad lying on his back, unconscious. Yanking the curtain aside, Wolford called for help, then turned to assist his friend. As he reached for Bjornstad's hand, darkness swept over him and Wolford passed out, falling atop Bjornstad's body.

The three men had been inside Columbia for less than a minute.

At 9:20, a Rockwell quality inspector, Jimmy Harper, logged in at the work station. Harper proceeded to the orbiter to find Wolford lying unconscious on Bjornstad. Harper rushed forward to help. Wolford briefly regained consciousness, tried to rise, but collapsed again. As Harper struggled to free Wolford, dizziness overcame him and he also collapsed, falling backwards through the door and onto the metal grating outside.

Figure 3: Position of Victims in Aft Compartment (Illustration from official accident report)

Moments later, Nick Mullon, Robert Tucker, and another quality inspector, Don Corbitt, signed in at the same work station. Mullon headed toward his work assignment in the aft compartment, unaware of the crisis. When he reached the orbiter, he saw Harper collapse onto the platform and, inside Columbia, Wolford passed out atop the unconscious Bjornstad. (Mullon could not see Forrest Cole, who had collapsed out of sight within the orbiter.) Rather than returning to the safety of the emergency station and calling for help, Mullon rushed forward.

Yelling behind him to Don Corbitt for assistance, Mullon grabbed Jimmy Harper and pulled him onto the access ramp away from Columbia. Taking a deep breath, Mullon then crawled into the deadly compartment where he grabbed Wolford and dragged him outside to safety. Corbitt arrived and he and Mullon re-entered the compartment to try to rescue Bjornstad. Corbitt grabbed Bjornstad’s feet; Mullon squeezed farther inside to push Bjornstad out by his shoulders. As they dragged and pushed the unconscious man through the doorway, dizziness overtook Mullon; he collapsed, falling unconscious onto the access platform outside.

A few feet away on the access ramp, Jimmy Harper, the first man Mullon had pulled to safety, regained consciousness and staggered back to the 130-foot level of the RSS and called for help. Quality inspector Bob Tucker rushed to his aid and began assisting him while other workers put out emergency calls, including a page throughout the launch complex calling for assistance. Emergency crews scrambled to the launch pad to help.

It was now 9:22. Bjornstad and Mullon lay unconscious on the access ramp near Columbia. Unknown to anyone, Forrest Cole still lay trapped inside the orbiter.

Three miles away at the Launch Control Center, the Firing Room engineer controlling the GN2 purge heard the emergency call and asked for permission to immediately end the purge and switch back to air. In the confusion, he did not receive a response; a minute later he initiated the changeover anyway. Unfortunately, the automated process of opening and closing all the proper valves took time: another 90 seconds passed before breathable air flowed into Columbia and began to push out the deadly GN2.

Back at the pad Jimmy Harper now appeared stable, so Tucker grabbed a five-minute emergency breathing unit and raced back to the orbiter where he found Corbitt struggling to pull Mullon and Bjornstad onto the access ramp. He and Corbitt managed to lift the unconscious men up the 4-foot ladder to the ramp and away from danger. Tucker then looked into the aft section, searching for other victims. As he peered around the crowded, dimly-lit compartment, his face mask began to fog and he failed to see Cole's body lying deeper inside the orbiter. He left.

At 9:23, eight minutes into the disaster, a fire chief at the pad responded to the emergency calls and arrived wearing self-contained breathing apparatus. Entering the aft compartment, he discovered Cole passed out under the cables and pipes within the crowded compartment. He tried to pull him free, without success. Another fireman arrived and joined the chief, who was still struggling to free Cole. Together, they managed to drag Cole from the orbiter and onto the access platform.

It was now 9:28. Forrest Cole, the last worker to be removed, had been trapped without oxygen for over 12 minutes. Nick Mullon, John Bjornstad, and Cole all lay unconscious on the access ramp fighting for their lives. Workers raced to find emergency air bottles and began administering oxygen to all five victims.

A call to the Launch Control Complex Dispensary requested every available ambulance at the pad. Within minutes the first responding unit, ambulance KSC-4, roared down the 3-mile gravel drive to Launch Complex 39A. At that time, emergency responders were unclear of the nature of the emergency and feared the presence of hazardous materials. In fact, one of the frantic calls had suggested the possibility of an ammonia leak. Consequently, the pad Security Control officer erroneously ordered guards not to allow any emergency vehicle through the gate that did not have the proper emergency breathing apparatus. Ambulance KSC-4 arrived at the pad's security gate at 9:29 only to be denied entrance because it did not have such equipment. From his position at the pad, a security sergeant (call sign Badger 15) witnessed the delay and immediately radioed the guardhouse:

9:30:19: Badger 15—“Do not hold anybody in emergency traffic at Pad A gate!”

No reponse. The ambulance was still being held.

9:31:07: Badger 15—“Let the ambulance come up here! Let the ambulance come up here! I need 'em at the top!”

Still no response. Frustrated, the sergeant ran to his car and raced to the ramp to discuss the situation personally with the pad guards. At 9:31:40, the pad safety chief chimed in over the communication loop, ordering the guards to allow the ambulance in, stating that they did not need the breathing apparatus.

Finally, at 9:32:18, after a nearly three-minute delay during which Bjornstad, Cole and Mullon lay unconscious or dying, the guards cleared the ambulance to the pad. KSC Medical then ordered all ambulances to proceed directly through the guard gate to the pad without stopping.

Figure 4: Launch Complex 39-A and the guard gate where ambulance was held. (Photo courtesy of Rick Banke)

At the pad, emergency workers administered oxygen to the five men, but supplies quickly ran low. At 9:37, two minutes after ambulance KSC-4 finally arrived, a NASA safety officer placed another 911 call, demanding more oxygen bottles.

Mullon regained consciousness at the pad; Bjornstad and Cole did not.

Finally, rescuers were able to remove the men from the launch complex and rush them to the on-site medical facility. From there, the critically injured were airlifted by helicopter to area hospitals. For two of the victims, it was too late: John Bjornstad died enroute; Forrest Cole, now in a coma, succumbed to his injuries on April 1, without ever regaining consciousness.

Nick Mullon, who saved Harper and Wolford's lives by pulling them to safety, was flown to Jess Parrish Hospital in Titusville. His wife, Denise, was working at her bank when she got the call that there had been an accident involving her husband. She was told to go home, but not to speak to anyone. Word had already spread, however, and friends from around the community joined her while she waited for word of her husband’s safety. Finally, Denise got word that Nick had been admitted to Parrish and rushed to her husband’s side.

Findings

NASA immediately assigned a board to investigate the Launch Complex 39A “mishap.” For three months, the board pored over transcripts, work logs, and documents, and conducted scores of interviews. On June 19, 1981, they released their findings in a 476-page document entitled, “LC-39A Mishap Investigation Board Final Report.”

The “proximate cause” of the tragedy was clear enough: hypoxia caused by workers breathing a pure-nitrogen atmosphere. The men were exposed to this hazard because of failed communication between the test conductors and pad workers. As is often the case, however, many factors contributed to the accident.

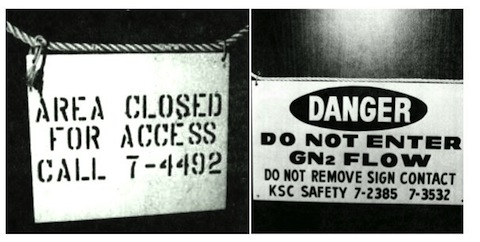

The investigation pointed to the failure of the Deviation documentation to specify the length of the extended GN2 purge, the decision not to tag the Deviation as “Hazardous,” and even to the signage at the access ramp: access to the orbiter was controlled by a simple chain with a sign reading “Area Closed,” which can be (and was) removed without Safety Personnel concurrence.

Figure 5: Restricted Access vs Hazardous Area signage (Photo courtesy of NASA)

Additionally, the board found that the breathing apparatus lockers were too far away for immediate responders, such as Mullon and Corbitt, to use. Even the access platform's design was cited as a hindrance to rescuers trying to assist the unconscious victims (see Figures 2 and 6).

Figure 6: Access Platform for Door 50-1 (Illustration from official accident report)

The board cited organization problems, as well. Test controllers at the Firing Room three miles from the launch complex wanted full authority over all test procedures. However, the on-site workforce at the pad saw this oversight as cumbersome in their efforts to perform their work. This led to the situation during the CDDT: Firing Room personnel running the extended GN2 purge while unaware that workers had been cleared at the pad to resume work.

Investigators compared the LC-39A Mishap, as it was called, with the Apollo 1 fire in 1967, which killed astronauts Grissom, White, and Chaffee. In both cases, a dry countdown test resulted in deaths because dangerous atmospheric situations were not tagged as “hazardous” (in the case of Apollo 1, the pure oxygen atmosphere in the crew cabin), contingency plans and equipment were inadequate or non-existent, emergency teams weren't prepared, and structural designs inhibited effective response. In fact, the board found that NASA had failed to comply with a 1967 Congressional request to establish procedures to review such operations in a timely and effective manner.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) also investigated. In November, OSHA found both Rockwell International and NASA at fault in the accident. For failing to prevent employees from entering the aft access compartment during a nitrogen purge, OSHA fined Rockwell $420. NASA received no fine at all. “That would amount to the government paying the government,” said OSHA officials.

In 1982, Barbara Bjornstad and Nancy Cole filed lawsuits against NASA, Rockwell International, and three other companies. According to newspaper reports in 1984, several of the suits representing the dead and injured were combined into a single settlement for three million dollars. In reality, neither the Mullon nor Wolford families was included in such a settlement.

“A Real Hero”

When Nick Mullon raced to help his fallen colleagues, he did so with no thought of his own safety. Even for this “dry” countdown test, the shuttle was loaded with many poisonous liquids and gases; the aft compartment could have been filled with hydrazine, ammonia or other deadly fumes. Knowing that literally every second counted, Mullon chose to plunge into the aft compartment to help, rather than lose precious moments by going back for breathing gear.

He paid a terrible price for his heroism.

The Nicholas Mullon who returned to his family appeared unchanged, physically. But the husband and father they knew—the laughing, energetic man with dreams of a better future—did not return from pad 39A. Nick now suffered from sleep disorders, severe anxiety, and physical problems. His ability to remember things was “gone.” He suffered from severe post-traumatic stress. His wife recounts that she would awaken at night to find him elsewhere in the house, hiding from his nightmares.

Unable to work, Nick began receiving workers’ compensation at a fraction of his lost salary. According to Mrs. Mullon, Rockwell and NASA offered the Mullon family no financial assistance. In fact, from the moment Denise was notified of the accident, the Mullons were instructed not to discuss it with anyone, including the press. Finally, in 1982, with looming medical expenses and Nick unable to work, the Mullons filed their own lawsuit, citing Nick's severe brain damage, sudden personality changes, and other psychological disorders.

Mark Horwitz, who represented the Mullon family, says Nick struggled daily with memory and emotional issues resulting from his hypoxia and nitrogen ingestion. One recollection still haunts Horwitz: Nick would be driving and suddenly stop the car, unable to remember how to get home—he would have to call his wife to come help him find his way back. “It’s bad enough to lose your mental faculties and not know it’s happening. But to realize your mind is damaged, to not be able to remember things you know you should, that’s,” he pauses, “that’s tough.”

Yet despite those struggles, Horwitz remembers Mullon as “a pleasant young man.” His associate in the case, Clifton Curry, agrees, saying “Nick was a great guy, just a hard-working family man . . . He was a real hero, and it was an honor to represent him.”

Also in 1982, William Wolford, one of the men Mullon saved, filed his own lawsuit.

Wolford, who was rushed into the hospital on a gurney bleeding from his nose and ears, was declared dead before being revived. “They had even tagged his toe,” says his wife, Susan.

Although Wolford was soon released, Mrs. Wolford says the accident “totally altered our lives. Bill suffered from non-stop severe migraines, I mean 24 hours a day, for three and a half years. He still suffers constantly from terrible back pain.” (While removing Wolford from the site, rescuers accidentally dislodged metal pins in his back from a previous injury.) According to Mrs. Wolford, even specialists at Duke University had no idea of his prognosis. “They had never heard of anyone surviving that much exposure to nitrogen.”

Yet according to both families, neither Rockwell nor NASA provided any emotional or financial support after the accident. “Nothing,” says Sue Wolford. “To this day, not one person from NASA or Rockwell has ever said one word to us about it. I had to find out what happened to Bill on the eleven o’clock news.”

In 1984, the defendants in the suits, Rockwell International, Pan American (who provided medical support at the pad), and Wackenhut Security (responsible for “protection of life and property at Kennedy Space Center”), settled with the victims’ families out of court. After paying off their attorneys and other debts, plus reimbursing the State of Florida for their workers' compensation (including medical costs), Nick and Denise Mullon cleared less than $60,000, the Wolfords somewhat more.

In 1996, Rockwell International was acquired by the Boeing Company. Representatives at Boeing did not return requests for comment.

Peace, at last

Over the next 11 years, Nick Mullon's health and mental faculties continued to deteriorate. In addition to the physical and emotional damage he suffered, survivor's guilt consumed him. “He would lock himself in the garage for days at a time,” Mrs. Mullon says. “He would disappear and I would find him practically anywhere. I might find him wandering on the sand dunes along the coast.” Another time, Nick fled to Washington D.C. in his effort to escape the daily torment his life had become. Denise found him living in a parking lot with other homeless men; Nick's guilt had driven him to believe this was where he belonged.

His physical condition continued to worsen, as well. Nodules appeared on Nick's lungs; even with oxygen, breathing became a daily struggle. Finally in April, 1995, after 14 years of battling the medical and psychological trauma—and only weeks before his son's high school graduation—Nick passed away, finally succumbing to the injuries he suffered on pad 39A.

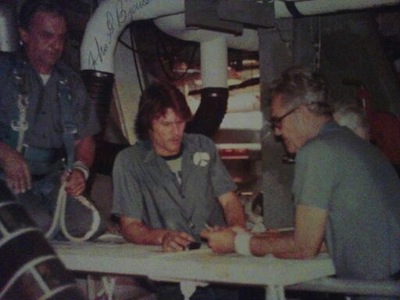

Figure 7: (L to R) John Bjornstad, Nick Mullon and Forrest Cole in the aft compartment of Columbia.

(Photo courtesy of Denise Mullon)

Not Forgotten

Less than a month after the accident, while orbiting the earth on the first space shuttle flight, commander John Young paid a personal tribute to the victims of the LC-39A tragedy. “I think it is only right that we mention a couple of guys that gave their lives a few weeks ago in our countdown demonstration test: John Bjornstad and Forrest Cole. They believed in the space program, and it meant a lot to them. I am sure they would be thrilled to see where we have the vehicle now.”

Thirty years later, the Space Walk of Fame Museum in Titusville, Fla., erected a monument “to honor those space workers who died in the line of duty.” Engraved along the top are the names John Bjornstad, Forrest Cole and Nicholas Mullon.

The memorial stands in tribute to those unheralded men and women who also made the ultimate sacrifice to explore the heavens, and reminds us that not every hero wears a pressure suit.

Figure 8: In the Line of Duty (Photo courtesy of Jeff Jackowski)

Copyright © 2013 by Terry Burlison

Terry Burlison graduated from Purdue University with a degree in Aeronautical and Astronautical Engineering: the same school/degree as Neil Armstrong and Gene Cernan, the first and last men to walk on the moon. He then worked for NASA's Johnson Space Center as a Trajectory Officer for the first space shuttle missions. After leaving NASA, Terry spent ten years at Boeing, supporting numerous civilian and defense space projects. Until recently, he was a private consultant for many of the new commercial space ventures. Terry is now a full-time writer. His web site is www.terryburlison.com.