Soon after I came to Los Angeles in 1970, I was called by a producer who offered me a job writing a science fiction screenplay. I was tied up with a book at the time; the producer asked me if I could suggest another writer for the project. I suggested Harlan Ellison.

There was a long, chilly silence at the other end of the phone. Finally the producer cleared his throat and said, "Do you, ah, know Harlan Ellison?"

No, I said, I didn't. I knew him only through his work. I had read some of his stories, and seen some of his television scripts.

"Umm," the producer said. "Well, let me tell you something—" and he launched into a short, energetic, and wholly unprintable description of his feelings on the subject of Harlan Ellison. The outburst ended as abruptly as it began, and he got off the phone leaving me completely mystified. I could only assume that Ellison and this producer had had some acrimonious dealings in the past. But that is hardly a rare event in Hollywood, and I thought no more about it.

As time went on, I ran into many people who had had acrimonious dealings with Harlan Ellison. There was an odd sameness about the way all these people talked. "He's very inventive, very enthusiastic, very talented," they would begin, "but—" and then they'd launch into a long and heated harangue, cataloging what they regarded as the innumerable abuses they had suffered at his hands. I was told that Ellison was a perfectionist; that he cared too much about his work; that he fought for his ideas; that he was demanding and quick to pull his name from any project which did not go as he intended—always substituting the sarcastic psuedonym, "Cordwainer Bird."

None of this elicited much sympathy from me. I saw nothing wrong with caring about your work and fighting for your ideas. I had been doing the same thing, and for my trouble I had been fired by Universal and then sued by that company. So I was in the position of admiring Ellison more with every new complaint I heard about him.

The people who spoke so bitterly about Harlan Ellison all mentioned something else, too. At the end of their diatribes, they would pause to catch their breath, and then conclude with: "And besides, did you see what Gay Talese said about him?"

Gay Talese had written an Esquire piece called "Frank Sinatra Has A Cold" which reported an encounter between Ellison and the singer. Ellison comes off as disrespectful, witty, and refusing to be bullied. It is hardly the protrait of a blackguard and cur which his critics felt it to be.

In the end, I suppose what impressed me most about these Ellison stories was the strength of feeling with which they were told. The facts—so far as they could be determined—were never very remarkable, but the emotional content was always fierce and highly charged. Somehow, Ellison had really gotten to them, and they would never forget it.

Some time later, this same Harlan Ellison began to attack me in print. His argument was that I wasn't writing good science fiction, which was fine by me—I didn't think I was writing science fiction at all—but it was irritating to be placed in an unwanted category and then told I didn't fit it well. I was back at Universal by then, and one day I was complaining about his attacks on me when a secretary looked up and said, "Do you, ah, know Harlan Ellison?"

No, I said, I didn't.

"Well," she said. "I used to be his secretary and I know him very well. Would you like to meet him?"

Harlan Ellison lives in the Los Angeles foothills, in a perfectly ordinary-appearing house, in a quiet suburban neighborhood. The inside of the house is as remarkable as the exterior is mundane; Ellison himself seems to take a certain pleasure in the unobtrusive outward appearance he presents to the community.

Inside, the feeling is sensual, almost sybaritic, with a quality of tension that comes from a barely controlled chaos. There are books everywhere, thousands of books, lining walls, tucked above doorways, filling closets, threatening to spill out and consume the living space. There are bizarre juxtapositions at every turn: signed Wunderlich prints, Soleri notebooks, sculpture from Mozambique, psychedelic book art set side by side in confusing profusion. It takes enormous energy to hold all this together, and Ellison himself appears to have boundless energy. He moves restlessly, talks non-stop, jumping from books to television to politics to sex to movies, taking up each new subject with considerable humor and aggressive enthusiasm.

He is not an easy man. His opinions are strongly held and his feelings strongly felt; he is not tolerant of compromise where it affects his life and his work. In someone else, this obstinacy might appear petty or fanatical, but in Harlan it is natural and attractive. It is simply the way he is.

Most strikingly, he is a genuine original, one-of-a-kind, difficult to categorize and unwilling to make it any easier. He demands to be taken on his own terms, and that aspect of his personality and his work is, I suspect, what has engaged both his critics and his large and passionately loyal following. He seems to be a kind of energy focus and no one who brushes against him comes away with an indifferent response. His advocates are every bit as vehement as his critics. Other writers have readers; Ellison has fans who will get into fistfights with anyone who says a word against him.

He doesn't write like anybody else. The same paradoxes and odd juxtapositions which appear in his house and in his casual speech, are present in all of his writing. What emerges is a surprising, eclectic, almost protean series of visions, often disturbing, always strongly felt.

In the end, these strong feelings drive Hollywood producers crazy but make extraordinary stories. After a long hiatus, there are eleven here, in top Ellison form—uncompromising, individual, and exactly as he wants them to be.

Hollywood

29 January 74

What you are about to read was written in 1974. It came to the page at the end of a decade of civil unrest in America that awakened a national social conscience too long in a state of narcolepsy. From 1963 till these words that follow were set down, this is what I saw and lived through in my world:

Race riots in Birmingham, Alabama that prompted President John F. Kennedy to call out 3000 troops; 200,000 Black and White Freedom Marchers congregated in Washington; investigative journalists began revealing the depth of outright lies we had been fed about what was happening in Cuba and Vietnam; Kennedy was assassinated; Lee Harvey Oswald was smoked; racist Ian Smith was elected Premier of Southern Rhodesia; the summer of blood in 1964 culminating in the Harlem riots and a year later the burning of Watts; escalation of the war in Vietnam; the march from Selma to Montgomery; Malcolm X shot to death in Harlem; Lyndon Johnson's presidency intensified the Vietnam incursions; ongoing conflict in the Middle East culminating in the Six-Day War; 50,000 people demonstrate against the Vietnam War at the Lincoln Memorial; Johnson driven out of office; Martin Luther King, Jr. assassinated; Muhammad Ali's boxing title taken from him because he refused to fight in Vietnam; Senator Robert F. Kennedy was assassinated; the Democratic Convention riots in Chicago; Nixon elected 37th President of the United States with the narrowest margin since 1912; the war in Northern Ireland escalates; the Russians occupy Czechoslovakia and a Czech student, Jan Palach, burns himself to death in protest; the "Chicago Eight" are tried; Lt. Calley and My Lai; Nixon starts to realign the Supreme Court to fit his needs; the war in Biafra; the Kent State University massacre; the U.S. bombs Cambodia, the war spreads to Laos; Idi Amin takes over Uganda; the Pentagon Papers; India and Pakistan go to war; Watergate; Nixon reelected; George Wallace shot; Britain imposes direct rule on Northern Ireland; arab terrorists killed Olympic athletes; Marcos assumes dictatorial powers in the Philippines; Agnew resigns in disgrace; the occupation of Wounded Knee; Allende of Chile is assassinated and his government overthrown with what will come to be revealed as the direct intervention of the CIA; and not too far off was the threatened impeachment and eventual resignation of Nixon.

And that was only the part of what was happening that shows up in my daily logs, only that part of the world around me that I haven't blissfully erased from memory. Don't ask what was happening in my personal life.

What you are about to read was the state of mind of a writer weary from a decade of violence, protest, pain and death. There were rivers of blood and mountains of dead. It was a bleak time, yet there had been concern; there had been the miracle of an entire nation coming to its feet with its fists raised against the inhumanity of the times.

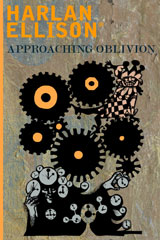

Since APPROACHING OBLIVION was first published, I have received hundreds of letters from people telling me that I shouldn't be so cynical, that I should look on the bright side. Most of them never bothered to notice that the words in the introduction were a decade old. They just wanted me to look on the bright side. And I would, really I would; if Jerry Falwell and Alexander Haig and Phyllis Schlafly and James Watt and Meyer Kahane and Qadaffi and Prime Minister Botha and little creeps like Lou Stathis were not out there standing in the dark side, waiting to make life unnecessarily crummy for you and me and lots of little kids who'll grow up to read this same introduction ten years hence.

All those letters chided me for being so downbeat. They started out by upbraiding me, but before they concluded they wound up offering apologia for themselves. "I haven't given up," they say. "I'm a good person! I don't litter, and I don't support the National Rifle Association, and I don't blah blah blah." And I look at those letters and think: Why do they feel guilty if they're so above reproach . . .do they, also, feel as if they're approaching oblivion?

And it's ten years since I wrote that introduction, and the spirit of Thoreau-like civil disobedience has dissipated like troublesome morning fog, and Jerry Rubin, when last seen, was selling insurance in Marin County, or something like that.

It's ten years, and to my amazement I'm still here. Most of my writer friends use word processors while I still bang away on this Olympia manual; they tore down the Brown Derby to make a parking lot; Walter Tevis and Phil Seuling and Bert Chandler and a bunch of my other friends have died; New York City ain't fun no more; and with the exception of Skor, you'll have a hard time finding a decent candy bar in the States; but I'm still here, still shaking my head in dismay at what Penthouse and the hypocrites who run the Miss America contest did to Vanessa Williams; still here anxious to look on the bright side, but somehow finally convinced that a few of us are doomed forever to view with alarm so the rest of you don't get too cozy.

Don't for an instant believe that I'm unaware of the unseemly hubris freighting such remarks, and I'd have it otherwise if I could . . .but there's this quote from Benedetto Croce (1866–1952), the Italian philosopher, statesman, literary critic and historian, that suggests, "Liberty is better served by presenting a clear target to one's opponents than by joining with them in an insincere and useless brotherliness," and I find myself again and again denied the simple pleasures of the bright side. So do me a favor, and don't write me no letters telling me I'm a sourpuss. In a world where John Landis continues to make movies, how can one be anything but alarmed. And don't send your toddlers to the McMartin pre-school.

Otherwise, just look on the following introduction as the bleat of pain from a guy who had just spent ten years in an unlovely universe. I feel okay today, and tomorrow night I get to see a funny movie, so maybe everything'll work out okay. But I sure wish the Clark Bar was still made with real chocolate . . .how about you?"

HARLAN ELLISON

12 September 84

Reaping the Whirlwind

If it hadn't been for my getting beaten up daily on the playground of Lathrop Grade School in Painesville, Ohio—this book would not be what it is. It might be a book with my stories in it, but it wouldn't be this book, and it wouldn't be as painful a book for me as it is.

You've noticed, of course. Everyone finally realizes it as an inescapable truth. Nothing we do as adults is wholly based on our adult reactions; it's always—to greater or lesser degree depending on how deep go our roots to the past—an echo of our childhoods. Your politics are either mirror images of your parents' politics when you were a kid, or they're rebellions against those politics. Somewhere in the physical makeup of the love-partners who turn you on are vague shadows of the high school cheerleader or basketball center who made your little heart go pitty-pat when you were dashing past puberty. If you were accepted and admired by your teenage peer group, you don't have the same gut-wrenching fears about going to parties where you don't know anyone as someone who was an outsider. If you had religion pounded into your head when you were young, chances are pretty good even if you've renounced formal church ties, you still carry the guilts and fears around in your gut. Or maybe you've come full-circle and have become a Jesus Person, if you've been disillusioned enough by the world.

No one escapes.

Our childhoods are sowing the wind, our adulthoods are reaping the whirlwind.

As true of me as you. No better, no nobler, no stronger, no freer of the past. Just like you.

In Painesville, I was a card-carrying outcast. "Come on, Harlan!" the kids would yell across Harmon Drive. "Come on, let's play at Leon's!" And like a sap, I'd clamber up from between the huge roots of the maple tree in our front yard, drop my copy of Lorna Doone or Lord Jim (or whatever other alternate universe I'd fled to because I hated the one I was in) and run after the gang of kids streaking for Leon Miller's house. I was a little kid, smaller than any other kid my age, and I couldn't run nearly as fast. That was always part of their equation, of course. And just as I'd reach the front steps, they'd all dash inside Leon's house, slam and latch the screen door, bang shut the front door with its big glass panes, and crowd behind the front window, sticking their tongues out at me and laughing. How I longed to enter that cool and dim front room where they would soon be playing Chinese Checkers and Pick-Up-Sticks.

Instead, their rejection always drove me to fury. I would slam my hands against the wooden frames of the screen windows and kick the glider on the front porch, always being careful not to tear the screens or damage the glider for fear of the wrath of Leon's grandmother. Then, when they tired of baiting me, and retreated into the dimness beyond to play, I would return to my book, where I could be brave and loved and capable of dueling Athos, Porthos and Aramis all in one afternoon.

On the schoolyard at Lathrop, I fared considerably worse than D'Artagnan. There, I was the accepted punching bag of bullies-in-training, whose names appear every now and then in my stories as characters who come to ugly ends.

I won't go into the reasons; they're all thirty years out-of-date and relevance. Suffice it that a gang of them would pound me into the dirt. And with a pre-Cool Hand Luke persistence, I would pull myself up and jump one of them, bury my teeth in his wrist and wrestle him to the ground. The others would kick me till I let loose. Up again, more slowly a second time, with a wild roundhouse at a thick, stupid face. Sometimes I'd connect and savor the eloquent vocabulary of a bloody nose. But they'd converge and plant me again. And it would go that way till I was unconscious or until Miss O'Hara from the third grade would dash out to scatter them.

But it wasn't the beatings that most dismayed me. It was having to go home after school with my clothes ripped and bloodied beyond repair. You see, I was grade school age only a few years after the Depression, and my family was anything but wealthy. We weren't destitute, far from it; but things were as tight for us as for most families in the Midwest at that time, and my parents could not afford new clothes all the time.

When I walked home from school, I would take the longest way around, often going to sit in the woods on the corner of Mentor Avenue and Lincoln Drive till it grew dark. I was ashamed and filled with guilt. And when, at last, I could stay away no longer, I'd go home and my Mother—who was a kind woman suffering with a troublesome child—would see me, she would cry and clean me up with mercurochrome and Band-Aids, and she would say (not every time, but even once was enough to make an indelible impression), "What did you say to get them mad?"

How could I tell her it was not only that I was a smart aleck? How could I tell her it was because I was a Jew and they had been taught Jews were something loathsome? How could I tell her it was easier for me to carry a broken nose and bruises than for me to act cowardly and deny that I was a Jew? The few times she had heard their anti-Semitic remarks, she had gone to school, and that had only made it worse. So I let her think I had started it. And swallowed the guilt. And built a reaction to bearing the blame that grew as I grew.

Now, as an adult, my reaction to being blamed for something I did not do is almost pathological.

Now, as an adult, I don't give a damn if I do tear the screens or damage the glider. I can think of nothing more horrible than what is done to Joseph K. in Kafka's The Trial.

Which brings me to why this book exists, and why it is the book it is. Preceding was preamble.

In 1971 the original publishers of this book, Walker & Company, published my collection of collaborations with other sf writers, Partners in Wonder. It was a lovely book but because of the ineptitude of Walker's then-art director, it was a book hideously overpriced. It seemed certain Walker & Company would lose a potload.

On the day the first copies came back from the bindery, I happened to be on a business trip to New York. My editor at Walker at that time was Helen D'Alessandro, a charming and talented woman who had tried to watchdog the Partners in Wonder project, who had been hamstrung by the excesses and inefficiences of a man who had mastered the art of passing the blame for his errors to others. Helen called me first in Los Angeles, to advise me the books were in, and finding out I was in New York, tracked me down and invited me to come in to the Walker offices. She knew all too well the horrors that had served as midwives to the birth of that book: galleys set so badly by computer that I had had to spend nine full days correcting them . . .insane typography that had jumped the cost of the book from a reasonable (at that time) $5.95 to an impossible (at that time) $8.95 . . .layout so berserk that it killed a certain reprint sale to the SF Book Club. She wanted me to see the book first.

I arrived at the offices of Walker & Company and Helen came out to the reception area to take me back to her office. When she came into the reception foyer, I was standing with a copy of Partners in Wonder in my hands. The woman on the switchboard had removed a copy from the carton when it had been delivered and had put it out on one of the display shelves as a gesture of kindness to an author she knew was soon to arrive. Helen's smile faded as she saw me standing there forlornly, leafing through a book twice the size and twice the price it might have been.

I looked up and saw her. She tried to smile again, but it wouldn't come. "Oh," was all she said.

In silence, we walked back to her office.

At that time, Helen shared editorial space with Lois Cole.

Lois Cole is one of the finest editors, one of the kindest persons, one of the most intelligent and charming people I have ever known. She was Margaret Mitchell's editor on Gone with the Wind and it was she, in part, who convinced Margaret Mitchell to change the title of that book from Mules in Horses' Harness to Gone with the Wind. She is a woman of uncommon perception and empathy.

She smiled up at me as I entered the tiny office, cleared a stack of manuscripts from a chair, and said, "I'm sorry, Harlan."

It was not the happiest day of my life.

We commiserated for a while, and I hung around the office doing some publicity work for the book with Henry Durkin. As five o'clock approached, I walked through the crowded passageway of the editorial offices to gather my coat and attaché case, when I heard someone call my name. I looked up and saw Sam Walker.

The president of Walker & Company is Samuel S. Walker, Jr. He is a tall, elegant man with fine manners, soft voice and too much gentlemanliness ever to permit him to become the sort of rapacious publisher who winds up with a corporate octopus like, for instance, Doubleday. We had never exchanged many words.

He motioned me to join him in his office, and when I'd entered, he closed the door and turned to me. His expression was sober and concerned. "I want you to know," he said, very gently, "that I know you aren't responsible for what has happened on this book. It's too common a practice in this business to blame a writer for what's gone wrong on the production end of a project. I want you to know that I'm aware we'll lose money on this book, but the fault does not lie with you. And I'd consider it a privilege to publish you again, if you'll trust us a second time."

He did not say: What did you do to get them mad?

He did not ask me why my clothes were ripped and my nose bloody and one shoe gone. He said he knew I was innocent of all wrongdoing.

It was a ten-year-old child getting an apology from an adult; the state bringing in "no true bill" and dismissing all charges; the hospital calling to say they'd mixed up the biopsy reports and someone else was dying of cancer; a page one retraction. It was one of the kindest, most sensitive things anyone had ever done for me, and it had occurred in an industry not overly burdened with thoughtfulness and kindness.

Sam Walker could not possibly have known what his words meant to me, nor with what echoes of my childhood they reverberated.

But because of those three minutes of concern, I wrote this book, and Sam Walker published it. So if it pleasures you . . .the thanks go as much to Sam as to me.

Originally, this was to have been a collection of already-published stories from several out-of-print books I'd written years ago. Larded in with the reprints were to have been three or four new stories. But as time progressed, I grew more and more disquieted with the idea of such a collection. In 1971, Macmillan published Alone Against Tomorrow, a collection of my stories that spanned the years from 1956 to 1969; though the pivot of all the stories in that collection was the theme of alienation, the book was also intended as a small, narrow retrospective of my work.

But a peculiar thing happened. It was one of the rare occasions on which I did not overblow my reputation, one of the few times my ego did not swell out of proportion to my worth. I had not gauged the popularity my stories had achieved in the three years preceding the publication of Alone Against Tomorrow, and was alternately delighted and dismayed by the letters I received praising the book but denouncing me for gathering together under a fresh title a group of much-reprinted stories.

It decided me without doubt that never again could I permit a supposed "new" collection to contain stories available in my other collections.

Approaching Oblivion was originally intended to gather together stories from then-out-of-print collections like A Touch of Infinity, Ellison Wonderland and Gentleman Junkie, with one or two stories available only in anthologies done by other editors.

The contracts were signed in November of 1970 and the book—which should have been no trouble to assemble—was supposed to be in Helen D'Alessandro's hands no later than six months thereafter. But the letters were starting to come in on Alone Against Tomorrow, and I began to procrastinate. Months, then years, went by, with polite notes of inquiry from Walker & Company. First, from Helen and then, when she departed the playing fields of literature to marry the brilliant poet, teacher and writer Anthony Hecht, from Lois, from the ineffable and indefatigable Hans Stefan Santesson, from Tim Seldes, from Henry Durkin, from Dedria Bryfonski who was my editor after Lois became swamped with other projects, and finally (though I may have missed a baton-passer or two in the whirl of personnel at Walker), from Ms. Evy Herr, my current shoulderer of anguish.

It is now four years after the original contracting for Approaching Oblivion. And the book is finished. It contains no stories ever included in my collections . . .though some of them have appeared in anthologies elsewhere. But that doesn't count. This book has my name on it. It is the product of my labors since 1970, with few exceptions. (If you're curious as to when a particular story was written, I've included the date of original emergence and the location[s] in which I wrote it, at the end of each piece.) So if I get letters complaining that these new stories are familiar, it's got to be from righteous Ellison buffs who buy every obscure magazine published, because these stories come from sources as diversified as Penthouse magazine, Crawdaddy, Galaxy and the August 1962 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction.

I'm glad I waited and let the contents of the book change. For several reasons. First, because most of the collections from which I'd have cannibalized stories are now coming back into print. Several paperback houses will be releasing almost all of my older titles in the next few years, thus ending the plaintive cries I hear at college lecture appearances, from my readers (each one with impeccable taste) who wail they cannot find my books on the newsstands.

Second, because now Sam and Evy (and Lois and Helen and all the other good people who were incredibly patient) have a new book, instead of a Frankincense creation cobbled-up from spare parts and dusty remnants.

And third, because the Harlan Ellison who signed those contracts in 1970 is not the same Harlan Ellison who writes these words today, in January of 1974.

Which brings me full circle to the schoolyard of Lathrop, and reaping the whirlwind.

In 1970, when I conceived the theme of this book—cautionary tales that would warn "this is what may happen if we keep going the way we're going"—I had just emerged from a decade of civil unrest and revolution. I was far from alone in passing through that terrible time. My friends, my country, my world had also gone through it. I believed in certain things, and I had gut-hatreds I thought would never cool. I had been in riots against the Vietnam war that had netted me time in jail and broken bones; I had been on civil rights marches and demonstrations that showed me the depths of inhumanity and craziness to which normal human beings could sink; I had lost many friends to dope and death; I had gone through an intellectual inferno that burned me out so I could not write for nearly a year and a half . . .and I was tired.

In Alone Against Tomorrow, I had included as a dedication for a book of stories about alienation, these words:

This book is dedicated to

the memory of

EVELYN DEL REY,

a dear friend, for laughter

and for caring . . .

And to the memories of:

ALLISON KRAUSE

JEFFREY GLEN MILLER

WILLIAM K. SCHROEDER

SANDRA LEE SHEUER

four Kent State University

students senselessly murdered

in their society's final act of

alienation.

The list is incomplete. There are

many others. There will be more.

And among the letters I received on that book, was this one, reproduced exactly as I received it:

June 10, 1971

Dear Mr. Ellison,

For your dedication of Alone Against Tomorrow, you mention the "four Kent State University students senselessly murdered . . ." Please be informed that these hooligans were Communist-led radical revolutionaries and anarchists, and deserved to be shot, whether by a firing squad or by the National Guard.

Your remarks ruined an otherwise good book. Nevertheless, I am happy for the opportunity to correct your thinking.

Sincerely yours,

--- ----------

I receive a lot of mail these days. Time prevents my answering very much of it—if I did, I'd have no time for writing the stories that prompt the mail in the first place. Some of the mail is pure, hardcore nutso. I roundfile it and forget it. More of it is reasoned, entertaining, supportive or chiding in a rational tone, and I read it and consider what's been said and usually reply with a form letter I've had to devise simply as a matter of survival.

Occasionally I get a letter that gives me pause. Mr. Chambers's letter was one of those. If I didn't know purely on instinct that he was running off jingo phrases that he'd swallowed whole, if I didn't know he was wrong purely on gut instinct or by my association with student movements for ten and more years, the reopening of the Kent State Massacre case by the Attorney General would convince me. So it's too easy merely to disregard a letter like that, and say, "What an asshole." But consider the letter. It isn't illiterate, it isn't rancorous, it isn't redneck or written on toilet paper. It is a simple, polite, straightforward attempt to straighten out what the correspondent takes to be incorrect thinking on my part. One cannot dismiss this kind of letter. It is from an ordinary human being, speaking about extraordinary events, and genuinely believing what he writes. Chambers really does believe those poor, innocent kids were Communist tools who deserved to die.

Now that scares the piss out of me.

That is approaching oblivion. It is reaping the whirlwind of half a decade of Nixon/Agnew brainwashing and paranoia. It is a perfectly apocalyptical example of the reconditeness to which The Common Man in our time clings with suicidal ferocity. I won't go into my little dance about the loathsomeness of The Common Man, or even flay again the body of stupidity to which "commonness" speaks. I'll merely point out that the Ellison who believed in the revolutionary Movement of the young and the frustrated and the angry in the Sixties, is not the Ellison of the Seventies who has seen students sink back into a charming Fifties apathy (with a simultaneous totemization of the banalities and mannerisms of those McCarthy Witch-Hunt Fifties), who has listened long and hard to the Chambers letter and hears in it a tone wholly in tune with the voice of the turtle heard in the land, who—when the defenses are down in the tiny hours after The Late Late Show—laments for all the martyrs who packed it in, in the name of "change," only to turn around a mere five years later and see the status returned to quo.

No, it is an Ellison closer to that scabby kid in Lathrop's dust who confronts you now. When I signed the contract for this book, I was prepared to ring out clarion calls about keeping the heat on The Establishment, making a better condition of life for everyone. But it's four years later and Vacca's The Coming Dark Age has been published which, if you haven't read it, you should go out at once and get it, and it plays the final notes of the death rigadoon for Society As We Know It . . .so why should I bother.

We are clearly on a slide-trough to destruction.

Watergate, the energy crisis, apartheid, holy wars, venality, vigilantism, apathy, corruption, fanaticism, racism, the deification of stupidity . . .none of these would be so terrifyingly prophetic of our rush to the grave were it not for the capabilities we possess to do ourselves in so efficiently and swiftly. The great lizards owned the planet for something like 130,000,000 years, but they didn't have slant-well drilling, pesticides, pollution, fast breeders, defoliants, demagogues, thermonuclear warheads, non-biodegradable plastics, The Pentagon, The Kremlin, The General Staff of the Peoples' Army, Ronald Reagan, Richard Nixon and the FBI.

Poor lizards. What joys they missed. Had they not been so culturally deprived, they might have sunk into the swamps in a mere three thousand years.

If it sounds as though I still care, disabuse yourself of the idea. I've done too many college lectures. I've seen too many classrooms filled with the no-neck children of parents whose motivation in life was, "My kid's gonna have the education I dint have." I've seen too many of those kids nodding off between Chaucer and Suckling, and I have grown disenchanted. You've let it ride too long, troops. You've frittered and fiddled and enshrined the hypocrites and slaughtered the dreamers, and now you can only get five gallons in your gas tank.

And if I've learned a lesson from that terrible time of fire and blood, it is that most reformers in the pure sense are clowns, shouting into the wind, balming their own guilts and making no ripple whatever. For every Gandhi or Nader or Bertrand Russell or Thoreau, there are a hundred thousand Nixons to stifle freedom of expression, joy of living and preservation of the past. (My self-disillusionment in this area shows itself in the story "Silent in Gehenna," included in this collection.)

As for the future, well, I'm brought in mind of a quote by Albert Camus:

"Real generosity toward the future lies in giving all to the present."

And the present is being ripped-off and screwed-over by the omnipresent philosophy of I'm all right, Jack, which is a working-class Englishman's term for screw you, baby, I've got mine. It's your future, and you don't seem to give a royal damn what happens to it.

So the Ellison who writes this is a little more calloused and tougher than the one who went to Selma with King in March of 1965, less hopeful and prone to sweeping gardyloos. The Ellison sitting here now is an older version of the kid from Painesville who stopped trying to buck the tide of bigotry and stupidity and merely cut out to find the rest of the world.

Had I done this book in 1970, as originally planned, you'd find in this space a clarion call to revolution, a resounding challenge to the future. But it's four years later, Nixon time, and I've seen you sitting on your asses mumbling about impeachment, I've gone through ten years waiting for you to recognize how evil the war in Vietnam was, I've watched you loaf and lumber through college and business and middle-class complacency, pursuing the twin goals of "happiness" and "security."

What fools you are. Happy, secure corpses you'll be.

You're approaching oblivion, and you know it, and you won't do a thing to save yourselves.

As for me and you in this literary liaison, well, I've paid my dues. Now I'm merely going to sit here on the side and laugh my ass off at how you sink into the quagmire like the triceratops. I'm going to laugh and jeer and wiggle my ears at your death throes. And how will I do that? By writing my stories. That's how I get my fix. You can OD on religion or dope or war or McDonald's toadburgers, for all I care. I'm over here, watching you, and giggling, and saying, "This is what tomorrow looks like, dummy."

And if you hear me sobbing once in a while, it's only because you've killed me, too, you fuckers.

I'm stuck on this spinning place with you, and I don't want to go, and you've killed me, and I resent it, and the best I can do is tell my little tomorrow stories and keep laughing as the whirlwind whips the dirt in the playground at Lathrop grade school into an ominous dust-devil.

HARLAN ELLISON

Los Angeles

January 1974