Fire and Ice

Grantville

Reardon Miller liked to joke that he had six jobs: his real job, and the five that certain clients of the Grantville Research Center thought he was doing. As the token male at the GRC, he was the researcher nominally assigned to those clients who were obviously very uncomfortable with the idea of working with a female researcher, but who were trying to be polite and not say so.

The would-be clients who weren't polite about it were just shown the door.

Reardon had a plan of action for, as he put it, "weaning the clients away from himself." (He said this with full recognition of the incongruity of applying the word "weaning" to the process of switching a client from male to female support. ) The first step was to introduce the female researcher as his assistant. The next was to let her deliver progress reports. Hopefully, the client would notice how knowledgeable and articulate she was. And finally, she would deliver the final presentation, with Reardon beaming benevolently in the background. Once the client expressed his thanks for the work, Reardon would lower the boom: "I'm just the pretty face here, this lady did all the research."

"Okay, Christine, we've got another client, name's Olafur Egilsson, a Lutheran minister from Iceland of all places. Something of a hardship case; he and his family—in fact, his whole congregation—got captured by the Barbary pirates.

"Okay, Christine, we've got another client, name's Olafur Egilsson, a Lutheran minister from Iceland of all places. Something of a hardship case; he and his family—in fact, his whole congregation—got captured by the Barbary pirates.

"Wow. How did he escape?"

"He didn't. They released him to ask their friends and relatives, and the king of Denmark, for ransom."

Christine raised her eyebrows. "But—"

"But Denmark had just gotten its ass kicked by Count Tilly, so the royal cupboard was bare. And the Icelanders are rather like hillbillies with fishing boats. . . . They don't have much in the way of resources, other than fish.

"So your job is to find goods that they can trade to the pirates, or sell somewhere for lots of cash.

"He's pushing seventy, we think, so we are going to reduce the shock to his system of how we do things in Grantville. I will be introducing you as my assistant."

"Great, I have three strikes against me; I'm young, I'm Catholic, and I'm female."

"So don't talk religion. "

****

Hendrick Trip steepled his fingers. "Well, you certainly did your homework, Miss Onofrio."

Christine smiled at him. "Thank you. I am just an apprentice researcher, but I try to be thorough."

The two of them were sitting in one of the conference rooms at the Higgins Hotel. Trip had rented it, and had been conducting meetings there all day.

"As my agent told you, my uncle Elias is a former partner of Louis de Geer. Our families still cooperate, and since I was coming to Grantville on my own business, Count Louis asked me to meet with you.

"He was quite interested in what you had to say about the aluminum industry in late-twentieth century Iceland. That aluminum was more than ten percent of its exports, and that it made it from imported alumina very cheaply, thanks to its vast energy resources, both hydroelectric and geothermal.

"You are of course correct that Louis de Geer is interested in aluminum production. It is not a secret anymore that he has been acquiring bauxite and cryolite toward that end.

"And it's also true that the availability of electricity is one of the bottlenecks in producing aluminum anywhere outside Grantville. Magdeburg or Essen.

"Alas, Herr de Geer has asked me to inform you that it would be premature to invest in a hydroelectric plant in Iceland at this time. While the coal-fired plants we have access to now are certainly less efficient than hydro, they are adequate for our current production level and we can still charge a high price for aluminum. More than enough to cover the cost of the coal.

Perhaps in a decade, he will reconsider the issue."

Christine caught herself nervously chewing on a pencil. "What about the advantage of the proximity of Iceland to Greenland, where the cryolite is mined?"

"I am no technical expert, but I have been told that the cryolite is just a flux, it is not consumed in the reaction. So De Geer didn't need a lot of cryolite to start, and only needs enough in a future to replace that which is lost by evaporation, or when the dross is removed from the smelter. "

"The cryolite can also be used to make soda ash."

"Indeed it can, and I believe that was the back-up plan if aluminum smelting proved impractical. But Iceland doesn't have significant wood or coal, and so—barring those hydroelectric or geothermal power plants—it's hardly the place to base a chemical plant."

"Well, I'm sorry for wasting your time." Christine began collecting her papers and stuffing them into the portfolio case her mother had given her.

"It wasn't a waste of time. I wanted to meet you."

Christine's eyes widened. "Me?"

"My family is always on the lookout for bright young people. Your teachers wrote to me that you are in the advanced track. When you graduate high school—next year, is it?"

She nodded, looking slightly dazed .

"Think about coming to work for Trip Enterprises. We even have a branch office in Grantville now, although your star may rise faster if you're in Amsterdam."

****

"German Sugar, Not Made by Slaves," Reverend Egilsson read. "Each ton of New World Sugar costs two human lives."

He handed the can back to the storekeeper. "Is it true?"

"Which part? The German sugar is real enough. There's a kind of sugar-rich grass which was grown in Grantville, called 'sorghum corn.' They used it as a fodder before the Ring of Fire. When the Americans discovered how expensive sugar was in this day and age, they decided to extract sorghum sugar. The sorghum is fast-growing and produces lots of seeds, so more and more acres are planted every year."

"What about the cost in lives?" Egilsson asked.

The shopkeeper stepped off the ladder he had climbed to reshelve the can. "Well, that's what the Anti-Slavery League pamphlets say. I've never met a slaver myself."

Lucky you, Egilsson thought.

"The pamphlet said that in the African slave trade, there are many deaths at sea, of crew as well as of slaves," said the storekeeper. "And the life expectancy in the sugarcane fields is only ten years."

"You seem to have studied the pamphlet carefully," said Egilsson.

The storekeeper smiled sheepishly. "I see it often enough.. When I run out of sugar from sugarcane, I set the German sugar out front, and leave a stack of those pamphlets nearby."

"Does the pamphlet say anything of the Turkish slave trade?"

"The Barbary pirates, you mean?" The storekeeper frowned. "I don't think so. But then, they don't grow sugarcane on the Barbary coast, do they?"

"Not on the coast, but in Sous, in the Berber kingdom of Tazerwalt to the south, they do."

"You know, the Anti-Slavery Society has an office in town. It's over by the Golden Arches; you can take the senior citizens bus there."

"Unfortunately, I don't qualify as a citizen of the town."

"Oh, they don't mean 'citizen' in the German sense. They'll take anyone that's, um, rich in life experience."

****

Reverend Egilsson found the ride on the bus to be quite remarkable. The bus rode on a strange black material that Egilsson took to be some kind of smooth lava rock. The bench seats, each sitting two, were comfortable, and there was little vibration as the bus forged ahead. The hum of the motor was a bit disconcerting, however.

He introduced himself to his seat companion, who was Edgar McAndrew, an up-timer in his seventies. Eventually, Egilsson revealed his purpose in coming to Grantville.

"Well, lordy me," McAndrew said. "You have certainly survived a lot. But I'll tell you what you should do, Rev. I'm retired now, but I was once one of the best salesmen in the U S of A, in my lines; I have the achievement certificates and statues to prove it.

"You need to get one of the GRC youngsters to make a list for you of old, rich people. The young rich, they're just thinking of making money. The old rich, they get worried about what'll happen to them when they come before the pearly gates, on account of all the dirty tricks they played on the way up the ladder, and they start giving to charity. You tell them that ransoming some of the Icelandic captives, people they don't even know, will count for a lot in Heaven."

Reverend Egilsson pondered this nugget of wisdom. "The GRC is trying to find new products for Iceland, so that we are prosperous enough to pay the ransom ourselves."

McAndrew snapped his fingers. "Hey, I've got an angle on that, too! If the business plan's a good one, then sell stock to the old misers. You prod them with the carrot of maybe making more money and the stick of going to Hell if they don't help. There's nothing like the iron fist of greed in the velvet glove of charity. Or something like that."

The ex-salesman reached for the stop cord, and pulled. "Get off when the bus comes to a halt, Anti-Slavery office is to your right. God bless you, Reverend."

"May God have mercy upon you."

The ex-salesman chuckled. "At my age, mercy is infinitely preferable to justice."

As he disembarked, Reverend Egilsson mentally reproached himself for not lecturing the ex-salesman on the evils of Popery, with particular reference to indulgences, and the concept that someone can buy himself into Heaven. However, Kastenmayer had warned him against provoking religious arguments with up-timers, and Kastenmayer, as the resident Lutheran preacher, would have to live with the consequences of any disturbance caused by Egilsson.

Anyway, with Egilsson's stop approaching, there hadn't been time to properly educate the up-timer as to his doctrinal oversights.

****

The man behind the desk at the Anti-Slavery Society stood up when Egilsson entered his office. "Please come in, make yourself comfortable. I am the Reverend Samuel Rishworth. What brings you to the Society office?"

The Reverend Egilsson told him.

"A sad story, and all too common. The Society has a committee studying the Barbary slave trade; perhaps you should speak to them. But I must warn you, it is Society policy not to pay slave owners to free their slaves. I hope you understand why—it would just encourage more slave-taking, would it not?

"Instead, we educate the public as to the immorality of slavery, and we seek to make slavery uneconomical in a variety of ways. Making it possible for Europeans to work in the tropics, for example. Organizing boycotts of products made with slave labor. And commissioning privateers to harass slave traders. "

Rishworth started pacing, hands clasped behind his back. "Until the Ring of Fire, opponents to slavery were few. I was once the minister for the Puritan settlement of Providence Island, in the Caribbean. When we sailed across the Atlantic, we prayed that God would shield us from the Turk. Yet we were quick enough to buy slaves from the Dutch once we were ashore.

I saw the hypocrisy in this, and preached against it. And eventually I practiced what I preached; I hid fugitive slaves, and eventually fled with them aboard a USE ship that visited the island.

"If there is one thing you need to know about the Americans, it is that they are adamantly opposed to slavery. If you read their history books, you will find out that they fought a very bloody civil war to get rid of it. Since the State of Thuringia-Franconia adopted the American legal system, slavery is already illegal here. And I know that the Committees of Correspondence want to make that part of USE law, generally. Having the ability to grow sugar at home has strengthened their position."

Rishworth stopped short. "I'm sorry. Once a preacher, always a preacher."

"I understand. But is there nothing you can do to help me?"

"Perhaps not in the short term. But our committee would like to find a way to persuade the Barbary states to at least treat their captives as prisoners of war, not slaves. And we hope that we can find goods they want to buy and goods they can sell us, so we can engage in peaceful trade instead of preying on each other. "

"Reardon Miller of the Grantville Research Center, and his assistant, are trying to find goods which Iceland can trade to the pirates in exchange for its people. Or at least, which Iceland can sell to someone in order to raise the ransom money."

Rishworth nodded. "That's a step in the right direction. If they like the goods, perhaps in the future they will accept trade as an alternative to war. And if not, then perhaps with increased prosperity, you can afford better defenses."

****

Reardon Miller peered through the blinds.

Christine came up behind him. "What are you doing, Mr. Miller?"

"There's a busker out there. He's drawing quite a crowd. Never thought I'd hear someone playing 'Yesterday' while looking like an escapee from the Renaissance Faire. Give a whole new meaning to the word, don't you think?"

He turned to face her. "I am sorry the aluminum idea didn't work out. You're looking cheerful, so I assume that you've come up with something else."

Christine drew herself up, and announced, "Rhubarb."

"Sounds like a password to a speakeasy in a Groucho Marx movie. Why rhubarb?"

"The 1911 encyclopedia said that rhubarb was grown in Iceland. And I asked around and rhubarb is more expensive in the here-and-now than cinnamon, opium or saffron. You're looking at around sixteen shillings a pound." That worked out to more than three hundred USE dollars.

Reardon nodded. "What's the catch?"

"What do you mean?"

"If the price is high, it's for a reason. It's hard to grow, or it comes from far away, or they shoot you if you try to take it from where it grows naturally, or it's illegal. Find out what's the catch."

Christine sighed. "I will."

****

"By the King of the Night," said Cornelis Janszoon van Sallee. "I almost wish I hadn't thought to look up what the American books said about the future of al-Maghrib." In Arabic, the "al-Maghrib" meant the setting sun, and by extension, the western limit of Islamic expansion—the coast of North Africa. Which, Cornelis had learned, had become the twentieth century countries of Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya.

Cornelis was the son of the Corsair Admiral Jan Janszoon—Murad Reis—and his father had sent him to Grantville to study their military technology. Garbled rumors of their mechanical marvels had come even to Sale in coastal Morocco, the capital of the Pirate Republic of Bou Regreg, and the home of what the English called the "Sallee Rovers."

"Forewarned is forearmed, sir," said Sergio Antonelli. Antonelli, who had visited Grantville before, was captured by Cornelis' father and commandeered to serve as Cornelis' servant, guide and protector during his stay in Christian Europe. Antonelli's son remained in Sale, as a hostage.

Cornelis took another bite from the American apple in his hand. "This is quite good, but I've had enough. Want the rest?"

Sergio accepted it gratefully.

Cornelis returned to his earlier train of thought. "Still, this Thomas Jefferson—may the fleas of a thousand camels infest his armpits—humiliated the Algerines. The Tripolitans, too. I fear that this Michael Stearns would be no kinder to those of the true faith than Jefferson, and that his ships will be more powerful."

"There would be no reason for the Americans to harm your people if you didn't take slaves," said Antonelli. It was something he wouldn't have dared to say a few months ago, when their trip began, but Janszoon even in the beginning had been strict but not cruel, and lately had shown him some small kindnesses. Like the offer of the apple.

"Yes, well, all unbelievers are fair game. Besides, if my father made peace with all countries today, he would lose his head on the morrow. We must have a nation to cruise against, the richer and weaker the better.

"But perhaps my father will make a peace treaty, or even an alliance, with the USE. Are they not at war with the English, the French and the Spanish? Are we not their friends, as the enemies of their enemies?"

Antonelli objected to this reasoning. "Temporarily, at least, there is peace. The members of the League of Ostend have been licking their wounds since June of last year."

"Pah," said Janszoon. "I would have liked to have seen the USE forces at war. Here in Grantville, all I have seen fired are a few small arms. They are excellent weapons, but I need more to impress my father."

Antonelli nodded. "We could visit the airfield and watch the planes take off and land. "

Janszoon clapped his hands. "Excellent idea."

"And we could go up to Magdeburg, see the Swedish troops at drill, and continue on to Hamburg where the ironclads were in action. Perhaps an ironclad will even be in port."

"Even better!"

Antonelli had finished the apple and was about to toss the core away.

"Wait, give it to me," Cornelis ordered.

Antonelli handed it over. Cornelis hefted it, and threw it at a squirrel that was sitting on a stump some yards away, licking its paws. It squawked indignantly when it was struck.

"A hit! A palpable hit!" Cornelis crowed. "I am quite the marksman, am I not? Too bad that military technology has advanced a bit beyond stone throwing."

****

Christine looked disapprovingly at Reardon Miller's desk. "It's a mess, Mr. Miller. I could organize it for you."

"No, please don't," he admonished. "I know where everything is; I have a system. Anyway, what can I do for you?"

"You were right, Mr. Miller."

"It's so nice to have a young lady tell me that. Or a lady of any age, now that I think about it. What was I right about?"

"The price of rhubarb is high because it comes all the way from China. By the time we could get the seeds from the Chinese and have the Icelanders raise a crop, the captives would have died of old age."

"I see. So, what's next?"

"Back to the library, I guess."

"Are you sure?"

Christine paused. Miller suddenly seemed fascinated by the papers on his desk.

"That . . . sounds like a trick question. . . ."

Miller started humming the "waiting for the contestants to answer the big question" music from Jeopardy.

"Please, Mr. Miller, I'm an apprentice researcher. Take pity on me." She batted her eyelashes at him in an exaggerated manner.

"It's a mistake to rely exclusively on books, Miss Onofrio. Never underestimate the value of intelligence collected by talking to human beings."

"Human beings. . . . Oh, like the garden club members?"

Miller nodded. "There are those in town who like rhubarb pie. So perhaps you can find some rhubarb seeds in Grantville. Bit less of a trip than China, don't you think?"

****

"Well, Hannah, for your sake, I hope you've produced an egg today," said Catherine Genucci.

"Come on, girl, let me have a peek." She tried to shoo Hannah out of her nest.

Hannah the Chicken from Hell declined to cooperate.

"Come on, now, be a nice lady, and . . . owww!" Hannah had pecked her.

Catherine licked the wound. "Oh, you nasty b . . . b . . . beast. I hope you're still barren, and I'll take the axe to your neck myself."

This charming pastoral scene was interrupted by a visitor. "Hi, Kathi!"

"Huh . . . Oh, hi, Christine. I thought you were working at the GRC." Christine and Kathi were born the same year, and knew each other from both school and church.

"I am, I'm here on business. So, are you the Queen of Hearts today?"

"I am, I'm here on business. So, are you the Queen of Hearts today?"

"The Queen . . . Oh, 'off with her head.' I hope so."

"I don't suppose you grow rhubarb here?"

"Rhubarb, no. But Mom might know who does. You want to talk to her?"

****

"Some more milk and cookies?" asked Fran Genucci.

"No thank you, Mrs. Genucci," said Christine. " But I hope you can answer some questions for me, being a Master Gardener and all."

"Well, I can try."

"Who around here has rhubarb seed? And how easy is it to grow?"

"Well, not me. I am more of a flower gardener, as perhaps you've noticed." She gestured vaguely in the direction of the front yard. "But there's rhubarb in Grantville, that's for sure. I think Mildred has it in her garden." Mildred was Fran's cousin, once removed, and another Garden Club member.

"But before you head over there, Christine, you ought to know, that people usually don't grow rhubarb from seed. It takes too long—two years, I think—and they don't grow true."

****

"Fran's right," said Mildred. "Wait until the plants are four or five years old, then divide the crown. You should be able to get eight or ten divisions from a single parent."

"But would they survive a trip to Iceland?"

"I'm sorry, dear, I am not sure. That's weeks? Months? I suppose they'd have to sit in pots on a ship. Perhaps Fran's nephew Philip, would know? He's the one that stowed away on a ship to Suriname, because he was gooey-eyed over that botanist Maria Vorst, from Leiden. He came back with plant specimens."

Mildred cocked her head. "Why Iceland, if I may ask?"

Christine told her.

"Oh, the poor man. Well, I can explain to you how to grow and propagate rhubarb, and give you some divisions, and a seed pod too, but I can't make any promises that they won't be D.O.A."

****

"I . . . I . . . I'm back," Christine announced. With a pseudo-Austrian accent.

Reardon Miller laughed. If anyone looked less like Arnold Schwarzenegger, it was Christine Onofrio. He motioned for her to sit down.

"It's strange," she said. "According to the 1911 encyclopedia, Prosper Alpinus was growing rhubarb in 1608, in Padua. And he gave seeds to Parkinson, who gave them to a 'Sir Matthew Lister,' supposedly physician to Charles I. I was puzzled, since I heard that William Harvey was Charles' physician, so I spoke to Thomas Hobbes." The philosopher had come to Grantville in 1633, escorting young William Cavendish on his "grand tour," and after learning how the powers-that-be reacted to his writings in the old time line, had decided it would be healthier not to return to England.

"Hobbes says that at least as of when he left London, Lister had not been knighted, but that he had indeed been one of King Charles' physicians, and had served James I and Queen Anne previously.

"So I don't understand. If the Italians and the English both have the plant, why is it still so rare and expensive? The price I told you was from 1656!"

Miller clucked his tongue. "Your generation remembers the internet, so you expect everything to be communicated instantaneously. In the old days—and we are now living in the 'really old days'—information moved slowly, and people were even slower to capitalize on that information. I imagine that both Alpinus and Lister were thinking small. They found a trophy plant for their own herbal gardens, and they used it in their own medical practices, and that was it. Did the encyclopedia say when serious commercial production began in Europe?"

"1777," she admitted, "and then based on seeds a pharmacist got from the Russians in 1762."

"Hah! You see what I mean? Over a century to go from academic curiosity to commercial crop. But I don't doubt it will happen faster in this new time line. Just not in weeks or even months."

Christine pondered this. "Still, it doesn't look likely that there'll be much of an export market for Icelandic rhubarb, even if I can get it there safely. The English are ahead of us. And if they don't move forward with commercial production now, they can do so soon so pretty quickly once they hear what the Icelanders are doing. And the herb will grow pretty much anywhere in northern Europe, even here in Germany."

Reardon reassured her. "It may not be the solution to the ransom problem, but I am sure that the Icelanders would appreciate some more variety in their diet. I wouldn't imagine that fruit trees grow among all that ice and snow, and rhubarb makes a good fruit substitute. So it's progress, of a sort."

Hamburg, Germany

The ex-militiaman gestured toward a large pile of rubble. "That's what used to be the Wallanlagen. The main river fortress of Hamburg."

Cornelis Janszoon studied the ruins. There were multiple overlapping craters. A dozen? Two dozen? Cornelis lost count after a while. And the craters were deep, perhaps one or two fathoms. Some kind of mortar bomb? he wondered.

"How did they get a fleet down the river?"

"Fleet?" The German spat. "Just four ships engaged us. What they call 'ironclads.'"

'What range did they fire at?"

"A bit over a hundred yards." He pointed with the hook he now had in place of a hand. "That's where the lead demon-ship anchored."

Cornelis thought about this. That was point blank range even for a swivel gun. It wouldn't even be necessary to elevate the gun. A twenty-four pounder could shoot straight up to 300 yards, and had a maximum range of perhaps 4,500 yards. The ironclads should have been under fire from the fort for a long time.

"How many did you sink?"

"Sink! We barely scuffed the paint off them." It was an exaggeration, but not much of one; the Constitution , the lead ironclad, had picked up just a few dents. "After shooting at them for half an hour or more."

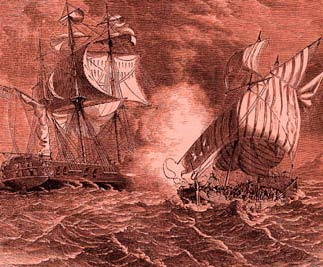

"Antonelli, when we get into Hamburg proper, I want you to commission some starving artist or another to sketch this scene for me. And another of the ironclads in action. I'll need something to show my father."

"Yes, sir. Interesting that the Swede hasn't rebuilt the Wallanlagen for his own use, now that he controls Hamburg."

The militiaman shrugged. "Perhaps it isn't worth rebuilding. Not if it would have to fend off ironclads, at least."

"I can think of another reason," said Cornelis. "To remind everyone that passes up or down the Elbe of just what his ironclads can do."

Cornelis couldn't help but imagine what those same ironclads would do to his home, the pirate town of Sallee. Or even to the more heavily fortified Algiers or Tunis.

The Barbary pirates had seen punitive fleets come and go. In 1620, Mansel had taken an English fleet massing almost five hundred cannon to Algiers, but all it accomplished was the release of the crews of two recently captured English ships. The same year, six Spanish warships exchanged fire with the Algerian harbor batteries; there was no damage on either side. The French didn't have a Mediterranean fleet that could seriously threaten Algiers until 1636, and its attack of 1637 was completely ineffectual, according to the histories.

The Dutch had better luck. In 1624, a Dutch squadron commanded by Admiral Lambert had appeared before Algiers. Lambert didn't threaten to lay siege to the city; he had captured some corsair vessels en route and threatened to hang the Algerians if the Dutch slaves weren't released. The pasha, agha and divan of Algiers conferred, and declined; Lambert made good his threat and promptly went off to collect more hostages. On his second appearance, the Algerians capitulated to his demand.

The treaty of 1626 provided that the corsairs could stop a Dutch ship and seize "enemy"—typically, Spanish—goods and passengers, but could not molest the crew, or seize other goods and passengers. It also provided that the Dutch were free to come to Algiers to trade, save that they couldn't export certain "forbidden items" of military value. The Dutch brought in herring, cheese, butter, and even beer and gunpowder, and took away wheat, hides, wax, and horses.

Still, in his time studying history and military technology at the Grantville Public Library, Cornelis had seen the handwriting on the wall. The encyclopedias revealed that the Barbary states had been protected as much by rivalry among the European powers—which saw the corsairs as tools to be used against their foes—as by the cannon and scimitars of their corsairs and the walls and batteries of their strongholds.

While for two centuries, most punitive expeditions, even the most successful, had ended with the Europeans paying ransom or tribute, once there was a general European peace, an Anglo-Dutch squadron had mercilessly bombarded Algiers, causing (and experiencing) much damage, and cowed Algiers and Tunis into temporary submission. And eventually the French invaded.

It was clear to Cornelis that military technology was going to develop at an accelerated rate, thanks to the appearance of Grantville, and it was only a matter of time before a single power dominated Europe.

And it was also clear that if that power were the USE, it would then act aggressively to suppress the slave trade, that of the Barbary Coast as well as the New World.

But in al-Maghrib, to make peace with all of the European powers would be suicide. Literally, not just politically.

Grantville

"Watcha' up to?"

Christine Onofrio, sitting on the bench eating her bag lunch, looked up. Her boyfriend was smiling down at her.

She smiled in return. "GRC stuff. I may have promised more than I can deliver."

"That Iceland project?"

'That's right. I'm still trying to figure out a way they can pay that ransom money."

"You know what I think? They should use the money to build a fleet and blast the pirates to smithereens!"

"That's your solution for every problem. Blow it up or ignore it. Very male."

He shrugged. "Why make things complicated?"

Christine wiped her mouth with a napkin. "I thought that perhaps, in the last four centuries, the Icelanders found something valuable on their island. I mean, look at Alaska. It used to be called 'Seward's Folly,' but then they found gold and later oil."

She took a deep breath. "Unfortunately, I was wrong. They don't have any minerals. No coal, no iron, and certainly no gold. No exotic animals or plants, either.

"So that leaves, as Iceland's fabulous resources, fish and sheep. And, of course, lava and ice. That's it. This project is 'Christine's Folly', I'm afraid."

"Talking about ice, would you like to go out for ice cream? I think you need cheering up."

Christine rose. "Twist my arm."

****

In-between licks, Christine said, "We're lucky to be in Grantville, you know. Plenty of electricity to run freezers, plenty of freezers to make ice. If we were off in Amsterdam, or Rome, we'd be out of luck. No ice in the summer. Ergo, no ice cream."

"Ugh," her boyfriend commented. "What did they do in the States, before there were refrigerators?"

"Don't know. Why'd you stop eating?"

He gave her a slightly sheepish look. "I was slurping it up too quickly, got an ice cream headache."

Christine snickered. "You weren't slurping it, you were inhaling it. Like a human vacuum cleaner."

****

Egilsson froze. That man. He had seen that man before. Where?

At the library, yes. But that wasn't why his pulse was suddenly racing. By the time he forced the deeper memory to the surface, the man and his companion had left the café, and disappeared out of sight.

He called over the waitress. "The man that just left—the swarthy one with the odd hat. I think he dropped this." Egilsson held up the book that he had been reading. "Do you know his name? I should bring it to him."

The waitress stood in contemplation for a moment. "No . . . Oh, yes, I do know him. That is Cornelis Jansen of Amsterdam. Do you want to leave the book with me, to give him the next time he comes?"

"No, I am sure I have seen him at the library. I will give the book to him there, I'd like to talk to him about it."

Not from Amsterdam, he thought. From the vestibule of Hell . . . the Corsair Republic of Sale. Cornelis Janszoon van Sallee was the son of the Dutch renegade Jan Janszoon, Admiral Murad Reis. As Olafur knew from slave gossip, Murad's ships had raided Reykjavik even while the Algierian corsairs had ransacked Olafur's Westmanneyjar. Olafur had seen Cornelis in Algiers, which he had visited as his father's agent.

Olafur mentally reviewed how much money he had left. It was, he thought, sufficient to buy an up-time pistol.

****

Christine hated being asked a question and not knowing the answer. It was like a tooth ache. You could try to ignore it, but sooner or later you had to do something about it. Christine headed back to the library to look up the prehistory of refrigeration. That led her to fish out the copy of Walden Pond she had to read for school.

On the weekend, she visited the nursing homes, figuring that some of the residents were old enough to remember the days before refrigerators were common. Then she quizzed the senior researchers at the GRC, many of whom were retirees, although not quite as old.

Gradually, she put together a new plan . . . "Third's the charm . . ." she said to herself.

****

Cornelis and Sergio left the Grantville Public Library shortly after sunset.

A voice spoke from the shadows. "Janszoon."

Cornelis turned, and froze when he saw the gun pointed at him. A gun held by Olafur Egilsson.

"Cornelis Janszoon van Sallee, the Pirate Prince. Glory be to the Almighty, that he would deliver you to me. At last I will have vengeance for the people of the Westman Islands, and the East Fjords, that were carried off as slaves to Algiers. Including myself and my family."

"You said, 'van Sallee,' so you know I am from there, not Algiers."

"Does it matter whether you are from Sodom, or from Gomorrah? Evil is evil. Your father led the devils of Sallee against the poor fishermen of Grindavik. For all I know, you were there yourself. But even if you weren't, you surely prospered from their misery.

Cornelis' companion cleared his throat.

"I have no quarrel with you," said Egilsson, "provided you do not interfere."

"I beg of you, listen to me," the companion pleaded. "My name is Sergio Antonelli and I am a Venetian merchant. Like you, I was a prisoner of the corsairs. I was given my liberty to guide Cornelis Janszoon safely to Grantville, and back. My son remains as hostage in the palace of Murad Reis, and if Cornelis does not return on time . . . things will go very ill for him."

Egilsson put his free hand over his heart. "I will pray for you and your son. But why would a lord of Sallee come to Grantville, but to learn their arts of destruction? How many more good Christians would die, or labor in servitude and degradation, if this servant of Satan is allowed to return to Sallee?"

That was when Christine arrived on the scene. She turned the corner, and spotted Egilsson. "Hello, Reverend Egilsson, I have good—What are you doing with that gun? Are those men threatening you? Should I call the police?"

Egilsson shook his head. "Do you Americans not say, 'God helps those who help themselves?' This man, this van Sallee, is a corsair spy, here to tell the pirates how to build your steamships and exploding shells and who knows what else. If I let him live, what will happen to poor Iceland? And if I cannot raise the ransom, then his death will be some modicum of vengeance for my countrymen."

Antonelli shook his head slowly. "Have you forgotten the words, 'Vengeance is mine, sayeth the Lord'?"

"Even the Devil . . . or a Papist . . . can quote Scripture."

"Please, hear me out," said Cornelis. "If you have lived in Algiers, then you know that it lives or dies by the slave trade. And Sale is the same. If there is any chance that this will change, it will be because I bring new arts home from Grantville."

Olafur made a noise that was almost a chuckle. "You expect me to believe that your father, the admiral, sent you to Grantville to learn how to beat your swords into ploughshares and your spears into pruning hooks?"

"It's true that he's interested in the up-timers' art of war. Their muskets, their cannon, and especially their flying machines. But what I have learned is that all the great powers of Europe also have their spies here, and are learning to copy up-time weapons. Some of them, at least. Sale is smaller even than Magdeburg, so how can it compete?

"If I can find a practical alternative to the slave trade . . . And I admit it's a big "if" . . . then perhaps we will consider peaceful trade. At least with some of the European states, I doubt that we will be quick to forgive Spain for the way it treated the people of Islam."

Olafur twitched slightly, but the gun barrel remained steady. "A nice speech. Antonelli, how much of that is true?"

"Sir, we have discovered that in the Atlas Mountains, Morocco has much mineral wealth. Minerals that might find a market—"

"And who would mine those minerals?" Olafur demanded. "I'll tell you, the poor slaves. The corsairs would redouble their efforts."

"Only if the European navies let them," said Antonelli. "And the USE has declared strongly against slavery. A black woman, Sharon Nichols, is now the USE Envoy in Rome. It is a message that all the diplomats and merchants of Europe can easily read.

"We would, of course, have to find goods that the people of Sale would want to buy, so they would welcome European trading ships. Based on the encyclopedias, we are thinking about cotton, tea, flour, and manufactured goods."

Christine spoke. "Reverend Egilsson, please. I think I found a way for Icelanders to pay the ransom. With goods that would be in demand in Algiers, if not in cash. Your family can be recovered. But not if you put yourself in jail for murder."

She tried to smile. "And you know, the library will revoke your borrowing privileges if you kill a fellow patron."

Ever so slowly, Olafur lowered the gun. "Can't have that," he said with an answering smile, albeit a fleeting one.

"Thank you, Reverend Egilsson. And if you wouldn't mind, please safety and holster it, too." He did so.

Antonelli put his hand on Janszoon's shoulder. "We'd best leave."

He shook the hand off. "Not just yet. Milady, what are the goods you speak of?

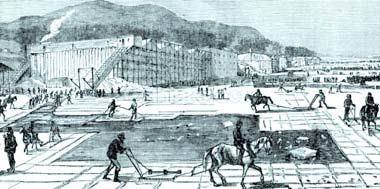

"Ice. Which Iceland has in abundance, you'll concede? Ice cream. Meats, fruits and vegetables preserved by being packed with ice. Mr. van Sallee, wouldn't those be wonderful luxuries for your people? And if not for them, they could be sold in Spain, or Italy, or Turkey. Or perhaps in Brazil, or Spanish America. Or even India."

"Ice. Which Iceland has in abundance, you'll concede? Ice cream. Meats, fruits and vegetables preserved by being packed with ice. Mr. van Sallee, wouldn't those be wonderful luxuries for your people? And if not for them, they could be sold in Spain, or Italy, or Turkey. Or perhaps in Brazil, or Spanish America. Or even India."

"The ice will melt along the way."

"There's a solution. There was once a big natural ice trade in America, in the nineteenth century. They cut ice at places like Walden Pond, and shipped it out to Charleston, and Havana, and even Calcutta, packed in sawdust. Or other insulation, but sawdust was the best."

"Sawdust?" asked Egilsson. "I met a woman engineer at St. Martin's who told me about her work at the steam sawmill."

"Sara Lynn," said Christine. "Perhaps you could have her ask them to donate the sawdust. It might be good publicity for the sawmill. And a good marketing gimmick, too, as it demonstrates how sawdust can be used."

Egilsson rubbed his chin thoughtfully. "In Iceland we have some glacial lakes. Jokulsarlon, Fjallsarlon, and Breidarlon. The lakes are filled with icebergs from the glacier.

And of course there are other lakes and rivers that freeze over during the winter.

"But if it's such a good idea, what's to keep someone from getting ice from Norway?"

Christina smiled. "I thought about that. Denmark, Norway and Iceland are all under Danish rule. And I would think King Kristjan feels bad, at least a little, about not paying the ransoms himself. If he gives us a monopoly for, say, ten years, on harvesting ice and snow for export, then that will give us a chance to get the business going. And it wouldn't cost him anything out of pocket."

"You seem to have a head for business," said Antonelli. "But where's the start-up capital coming from?"

"There are a number of possibilities," Christina told him. "We can send a proposal to Other People's Money, or one of the other investment funds. We could get a loan from a bank. Or we could scrounge up private investors ourselves. I sounded out Hendrick Trip—"

"Trip!" exclaimed Antonelli. "You move in more exalted financial circles than I ever did, miss."

"What about when the ice gets to its destination?" asked Janszoon doubtfully. "I don't want to discourage you, but it's very hot in Sale, or Algiers, in the summer when the demand would be the greatest, and since it's a novelty, I am not sure how quickly it would sell."

"Well, that's where you would come in," Christine explained. "Have an ice house built there in advance."

"Ice houses are very expensive," said Antonelli. "You have to dig a hole, then line it with stone. "

Christine disagreed. "I'm sorry, that's not true. At least that's not how we usually did it in the States, before there were refrigerators. We built most of our ice houses above ground, out of wood. There are old ice houses like that on a few of the farms in Grantville, I was told. "Perhaps some people took advantage of natural caves, but that wasn't necessary.

"And perhaps we could get some of the Science Club kids at school to test a few ice house models, and see what design works best."

"In the Maghrib, trees are not as common as they are here." Janszoon warned. "So wood can be expensive. But we do have matmoras, underground granaries, that may have some free space, and there are caves in the mountains."

"Do we have to worry about refrigerators driving us out of the business?" asked Antonelli. He didn't notice that he had said "we."

"Not for a few more years, I think," said Christine. "After all, refrigerators need electricity. And also there's some kind of gas in them. They're both in short supply, so initially the production will be limited. I would imagine that it will be a while before the Barbary Coast gets enough to meet the demand. And anyway, isn't it a bit short of water to make artificial ice?"

"You could say that," Janszoon admitted. "All right. I will demonstrate my commitment to finding a peaceful way by arranging for one of these ice houses to be constructed, once you can show me a reasonable business plan, and that you have investors willing to put up the money you need to harvest the ice, and that your model ice house can preserve ice."

"That's no commitment at all!" Egilsson's eyebrows were pulled down and together, as if they were magnetized. "If this, if that . . . You have promised nothing. Nothing at all."

"What do you expect? I know nothing of this ice trade, so I can't judge the practicality of it all based on my personal experience. Yes, the Americans did it in the nineteenth century, but perhaps it wouldn't work in the here and now. Even with funding, there could be trouble. A winter too mild to produce a decent ice harvest, or a winter so severe that you can't cut the ice. Or problems at sea."

"'Multa cadunt inter calicem supremaque labra,'" Antonelli quoted. It meant, "many things fall between cup and lip."

Janszoon nodded. "If I build this ice house, and no ice arrives, I will be a laughingstock, and an embarrassment to my father. Sale is governed by the Council of Corsair Captains, and his position as admiral is precarious. One sign of weakness, and they will attack him . . . like a school of sharks that has scented blood."

Christine worried her lip. "I think . . . Reverend Egilsson? I think he's making good points—"

"Good points? I . . . I suppose." The Reverend's expression could have curdled milk.

Janszoon seized upon this admission. "Then does my proposition sound fair?

Egilsson looked at Christine, then back at the provisionally reformed corsair. He sighed. "Fair."

****

Author's Note

Olafur Egilsson (1564-1639) is a historical down-timer. My description of his capture and subsequent adventures is based on Reisubok sera Olafs Egilssonar (The Travels of Reverend Olafur Egilsson) translated by Karl Smarri Hreinsson and Adam Nichols (Fjolvi, Ltd., Reykjavik, 2008). Antonelli's proverb is from the Adagia of Erasmus.

Samuel Rishworth is a historical down-timer, and his activities are, as far as I know, the earliest European opposition to the African slave trade. (Bartolome de las Casas had previously protested the Amerindian slave trade.) He appeared in my story, "Stretching Out, Part 4: Beyond the Line," Grantville Gazette 16.

Cornelis Janszoon and his piratical father were historical down-timers, both introduced in "A Pirate's Ken" (Grantville Gazette 15).

****