The Beckies

"Sir, Lieutenant Bartley reporting as ordered."

Lieutenant David Bartley reported to the quartermaster of the Third Division in Magdeburg with an apprehension that, had he known it, was completely matched by the apprehension the quartermaster was feeling. Colonel Paul McAdam was a Scottish mercenary in Gustav Adolph's service. Or he had been before he was transferred to Third Division. By now he was used to dealing with up-timers but Bartley had a reputation and up-timers were not, for the most part, all that comfortable with the way things were done in the seventeenth century.

"Ah. Lieutenant Bartley. I've heard about you."

"Good things, I hope, sir."

"Well, then. I suppose that would depend . . ." Colonel McAdam began, then petered off ominously. As it happened both of them were somewhat overanxious. David had been working with down-timer men of affairs since he was fourteen and was quite familiar with the way things got done in the here and now. He was more than half down-timer by this time. Well, maybe only a third, but it was an important third. He realized that palms got greased to get things done and, unlike most of the older up-timers, didn't resent it. It just was a part of the world he lived in. He got things done and he had been making money getting things done since he was fourteen.

"Have a seat, Lieutenant Bartley." Colonel McAdam gestured to a chair and continued as David sat. "What do you know about the supply situation?"

"Not as much as I would like, sir."

"Well, it's not that bad here in Magdeburg. We have the river and we're in the center of the, well, everything."

David nodded. In Magdeburg you could get almost anything you could get in Grantville and more of it.

The colonel nodded back, a single, quick jerk of his head and continued. "But it's not going to be that easy once the campaign starts. Even the best army in the world can't carry enough food and fodder to keep it fed very long in the field. The canning and freeze-drying would help, but there is very little of it so far when you're talking about feeding an army instead of a few rich people. What will help some, I hope, is the Elbe as we move into Saxony. But if we end up more than a few miles from the Elbe, we're going to have to do what we've always done. Buy from the locals. And if the rumors are right about Poland, that's going to be even worse."

"Buy?" David asked.

The colonel gave David a careful look then another quick jerk of a nod. "That's the best we can hope for, Lieutenant. Before the Ring of Fire we would have gone through the land like locusts. But we're not supposed to do that anymore and your job is going to be arranging to have us meet with merchants willing to sell the army food."

They discussed Third Division's discretionary funds and the logistics of the coming campaign. David asked about what the army would be taking, where it would get it, and how it would be transported. How, in other words, he could help. "I, ah, do have some connections in the business community, sir. I can see what sort of bargains I can find?"

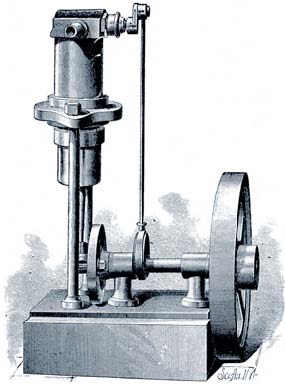

"I know up-time APCs are out of the question for transport, but can you get us steam wagons?"

"Not a chance!" David shook his head with more than a little regret. "Adolph Schmidt builds what I think are the best steam engines, for the price, in Magdeburg but he's at least six months behind on orders and the other two Magdeburg companies making steam engines are almost as far behind. The companies up in Grantville are even farther behind on orders. People are patriotic enough, but business is business and they have contracts with people who have already paid for their steam engines.

"Between you, me and every drover or muleskinner in Germany, a steam engine is worth at least three times the price of the equivalent number of horses—good horses, not nags half way to the glue factory. And that's mostly what they sell for. If I go to Adolph on bended knee, I may get him to bump us up on the order list to the tune of half a dozen steam engines or so. I'm a major stockholder, after all. But even if I do, using them to power wagons would mostly be a waste since they can power factories or river boats where you get more bang for your buck."

"Between you, me and every drover or muleskinner in Germany, a steam engine is worth at least three times the price of the equivalent number of horses—good horses, not nags half way to the glue factory. And that's mostly what they sell for. If I go to Adolph on bended knee, I may get him to bump us up on the order list to the tune of half a dozen steam engines or so. I'm a major stockholder, after all. But even if I do, using them to power wagons would mostly be a waste since they can power factories or river boats where you get more bang for your buck."

"Even half a dozen might help," Colonel McAdam pointed out. "As I said, we're likely to be using barges to ferry supplies up river to Saxony. At least at first."

"I'll see what I can do, sir."

The colonel nodded. "Good. But you're right, half a dozen steam wagons wouldn't be enough to make much difference. Do you know how much it takes to feed, clothe and house an army?"

"I know what the books say it takes, sir," David said. "I don't know how well the books agree with the reality."

They talked requirements then, in food and equipage. The answerer to how much supplies an army consumed came out to various values of "a hell of a lot" and "even more than that," now that they wouldn't be looting the country side as they marched.

That was something that Colonel McAdam agreed was very fine and noble but also something he wasn't convinced was practical. "I mean, if the other side is living in large part off the land and we're trailing along this monstrous logistic tail . . . it's a weak point the enemy can take advantage of." It was a problem that neither of them, nor anyone else in the Third Division's S4 section, had a solution for. Not then anyway.

****

David did beg steam engines off of Adolph Schmidt, but he only got four of the things. Then he spent his days till the Third Division headed for Saxony calculating tonnages, finding barges, working with drovers and merchants to arrange for food, powder and shot. And while he was making those arrangements, he noticed that many of the people who had goods for sale also had goods they wanted to buy. Value-added manufactured goods: plow blades, steel pots and pans, nuts, bolts, bearings, screws and screwdrivers, all sorts of stuff.

This wasn't all that surprising; the factories in Magdeburg and all along the lower Elbe where it continued navigable through most of the year, were producing at a phenomenal rate . . . but it wasn't enough. The full output of all the factories in all of the Germanies weren't enough to make a dent in demand. David was thought of as someone who could get stuff. Just as McAdam had asked him about steam engines, most of the people he dealt with were hoping he could use his influence to get something.

"You don't know what it’s like, Herr Bartley," Steffan Vogel complained bitterly. "I've got lands in pasture that could be producing wheat if I had the plows—new plows. I ask about the plows and I'm told there is a nine-month wait. Nine months, Herr Bartley. And meanwhile all the peasants are running off to Magdeburg to get manufacturing jobs."

And I don't blame them a bit, David thought, not greatly impressed with Vogel. Still, the man had grain for sale in Saxony. So David was polite.

After several such interviews where people like Vogel wanted stuff instead of money, David started to think. An army carried some of its supplies with it and it carried money to buy supplies as well. Before the Ring of Fire that money was silver coins. And even now it was partly silver. Oh, they would carry American dollars, the latest incarnation of them, USE Federal Reserve Bank Notes. They would carry American dollars to pay the troops, but not everyone was convinced that American dollars were good currency. So the army would also be carrying silver coins, minted by the USE Treasury Department, of a given weight and purity. The official name for such coins was silver slugs. Because they weren’t tied to the American dollar in any way, the exchange rate between them and American dollars was whatever the precious metals market in Magdeburg said it was. Third Division would receive them as part of their contingency funds.

All of which was perfectly standard and ordinary, except people like Vogel didn't want to be paid in silver slugs any more than in American dollars. They wanted plows and nuts and bolts and, well, stuff. What if, aside from American dollars and silver slugs, the Third Division were to take plows and nuts and bolts and . . . so on, to pay for the wheat and sausage and cheese . . . and so on, the division needed?

****

"The Third Division could make a profit on the deal, sir," David told Colonel McAdam. "We would be buying the stuff at golden corridor prices, then transporting it with the division, so no tolls or duties—no bandits for that matter—then selling at outland prices."

"Golden corridor?"

"Yes, sir. The Elbe up to the rail head and the rail line up to the Ring of Fire. The prices for most finished goods are lower in the corridor than just about anywhere else in the world. Still high by up-time standards, but . . ." David shrugged. For the most part, he didn't remember up-time that well any more, certainly not up-time prices. Prices for finished goods were low in the corridor and the price of labor was high, relative to the rest of the world. That wasn't constant, just an average. And people that didn't have the production machines tended to have real trouble competing. But that was another reason why the merchants and want-to-be manufactures in places like Saxony were so desperate for nuts and bolts. "If the Third Division can bring pots and pans, nails and screws and so forth with us, the local merchants will show up begging to sell us their grain so that they can buy our pots and pans."

But Colonel McAdam clearly wasn't impressed with David's notion. He gave one of those short sharp shakes of his head. "Pots and pans weigh a lot more than silver coins and paper money weighs even less than silver. If they will come for pots and pans, they'll come for silver."

The short sharp head shake had told David that the colonel had made up his mind. So he didn't point out that they would be "buying" the silver for precisely the same price they would be "selling" it for, but the pots and pans would sell for considerably more in Saxony than they would cost in the corridor.

Colonel McAdam wouldn't sign off on the division buying trade goods to cart with them on campaign. He did agree to let David do it on his own and let David's cargo travel with the army. David rented barges and hired troops who marched into Saxony, pulling hand carts and pushing wheelbarrows full of goods.

Summer Campaign Season, 1635, Saxony

"Damn and blast it!"

"Beg pardon, sir?" David said.

"He means it, doesn't he?" Colonel McAdam snorted. "How are we going to feed the troops if the local farmers won't take their own money? And your General Stearns is . . . most insistent that we be . . . polite . . . about it all."

The local money was worthless. The American dollars were acceptable, but only barely, just at the moment. Radio informs whether the news is good or bad. The American dollar, which had started out as the New US dollar, then become the SoTF dollar, was now transmuting into the USE dollar. They were all American dollars. At least, the government in Magdeburg said they were all "American dollars." However, the process of expansion had diluted the cachet of the original American dollar sent by God with the up-timers. Silver was preferred in Saxony at the moment and Third Division, the whole army in fact, hadn't brought enough.

"It's not helping that the USE dollar has been losing ground against the Dutch guilder for the last few months," David muttered. "Not all that badly, true, but it's got the Fed worried. Sarah said Coleman Walker is pitching a fit."

"Well, the locals aren't exactly snapping up our new American dollars with gay abandon," Colonel McAdam sneered. "They took the old well enough, but not the new. And don't even talk to them about the government chits, not without a sword in your hand. In the whole squad's hands, rather. I tried to talk to the general about this. Tried to tell him. But still!"

General Stearns had almost, but not quite completely, forbidden the use of sword point to persuade the locals to take the chits.

David went back to his office, frustrated. Colonel McAdam wasn't the world's best listener. David had actual material goods, real stuff that could be put to use. Sewing machines, the parts to make drop forges, batteries, rayon thread, all sorts of stuff. All in his own little supply train that Colonel McAdam didn't want to hear about, much less discuss. So the same merchants and farmers who were hiding their goods from the supply corps in general, were seeking David out and selling their grain and anything else they could think of before the rest of the army's supply division caught them with it and forced them to sell it for government chits which might or might not ever be worth anything.

All David really needed was . . . well, for his boss to get out of his way.

Meanwhile, the troops had to be fed. And there was only one way David could think of to get that done. Sell, sell, sell.

So he did.

****

Soon David had a reputation and almost didn't need the goods. Just catalogs.

"You're that Bartley fellow?"

"Yes, Herr . . ."

"Baum. Adolph Baum. I have some cattle to sell."

Indeed he did, David saw. Herr Baum must be representing an entire village, because he had quite a few cattle. "You know, Herr Baum, you can get more money if you take the cattle a bit up the road, to the main supply tent."

Herr Baum laughed. "I can get more of what they call money, young fellow. No offense to the Prince of Germany, but I'd just as soon not have those worthless chits."

"They're not worthless, sir."

Baum smirked. "You take them then."

It was hard to turn down an invitation like that, so David didn't.

David sent Johan Kipper out to look over the goods and come up with an offering price. And aside from smiling politely, stayed out of it. Sergeant Beckman did the negations. Both Johan and the sergeant were much better negotiators than David was. Besides, many of the people they were dealing with would have been really uncomfortable negotiating with an up-timer. Way too much like negotiating with a cardinal or a baron or something. So David sat back and smiled benevolently . . . some would say condescendingly. But, damn it, they expected condescension, the next best thing to demanded it. David could at least make it kindly condescension, rather than sneering condescension.

Then David would pull out his catalogs, they would go over what the farmers or the merchants needed and what was available at what price. Here David would talk. He would make suggestions about who had the best products for the best price, ask questions about what they were going to use it for, and make suggestions about possible alternatives. Once they had everything worked out, David's secretary would write out the agreement, and David and the customer would sign it.

And more often than not the customer would leave muttering about how "the up-timer was a proper noble, kind and understanding, not like the sort we have around here."

Next David would walk over to the main supply tent, transfer to the goods to the Third Division and receive the government chit that the merchant or farmer didn't want. That the customer was right not to want, because, as it turns out, there is a real difference between some farmer off in Saxony sending in a chit and an army officer with his own lawyer turning in the selfsame chit. The difference isn't so much of a question of will it get paid at all, though there is some of that. Mostly it's a question of when it gets paid.

David had access to the military radio, he had a lawyer in Magdeburg and knew several people in the Treasury. From the supply tent he went to the radio room and sent the codes on the chits to Magdeburg and the funds were transferred from the government account to David's account. Then David sent off another radio message to his agent in Magdeburg, specifying the purchases to be made and where they were to be sent. It would arrive in a few weeks or a couple of months, depending on the waiting list for that product. There was always a waiting list and the customers were told that as well. Still, they were happy with the deal for the most part.

Since David had set this up on his own hook and using his own credit, primarily as a way of helping to make sure that the army had the supplies it needed, he didn't feel the least bit guilty about the profit he made.

After all, it wasn't like they could buy such goods with Saxon thalers. John George's paper thalers were supposed to be exchangeable for one ounce of silver on demand in Dresden. Demanding that silver was a threat to the duke's realm and a palpable insult to the duke, both of which were criminal acts in Saxony. "Here's your silver, you're under arrest for treason against the duke" is not the sort of response that makes one want to run down to the treasury for some hard currency. To date, no one had actually received any silver in exchange for a Saxon thaler with a picture of John George on the front and now no one ever would. On the Grantville currency market the Saxon thaler was valued at about two cents American money. Well, it had been. When the first of Gustav Adolph's troops crossed the border, it dropped off the exchange all together. But they still circulated in Saxony because they were, mostly, all there was. Any silver currency in Saxony had obeyed Gresham's law and retreated to under someone's mattress.

After all, it wasn't like they could buy such goods with Saxon thalers. John George's paper thalers were supposed to be exchangeable for one ounce of silver on demand in Dresden. Demanding that silver was a threat to the duke's realm and a palpable insult to the duke, both of which were criminal acts in Saxony. "Here's your silver, you're under arrest for treason against the duke" is not the sort of response that makes one want to run down to the treasury for some hard currency. To date, no one had actually received any silver in exchange for a Saxon thaler with a picture of John George on the front and now no one ever would. On the Grantville currency market the Saxon thaler was valued at about two cents American money. Well, it had been. When the first of Gustav Adolph's troops crossed the border, it dropped off the exchange all together. But they still circulated in Saxony because they were, mostly, all there was. Any silver currency in Saxony had obeyed Gresham's law and retreated to under someone's mattress.

****

"Don't you Americans have a term for this? Profiteering, isn't it?" Colonel McAdam's sneer wasn't quite as confident as he apparently thought it was.

About the time they hit Dresden, Colonel McAdam noticed the profit David was making and was pissed. Both because he hadn't gotten in on it and because it wasn't anything the Third Division couldn't have been doing right along. David's initial proposal had been close enough to what he had ended up doing on his own that the evolution was obvious in hindsight. All of which made the colonel look and feel more than a little foolish.

"Sir, you gave me permission, and, no, I'm not profiteering. I also resent the suggestion that I am." It might be taking a bit of a chance, David thought, but he wasn't letting this blowhard start any rumors that might damage his reputation. If Colonel McAdam resented David's success, that was fine. Even so, David himself was out of reach because McAdam had specifically given David permission to do what he was doing.

"Humph. Your Sergeant Beckman, however . . ."

David glanced over at Beckman, then glared a furious glare at him. The sergeant wilted. "Sergeant Beckman was not authorized for that transaction, sir, as he will admit."

Sergeant Beckman's unauthorized trading of army supplies would probably have brought him up on much more serious charges if it had happened back up-time. Here in Saxony in the year of our Lord 1635, he might reasonably expect it to be ignored. Except, of course, that the colonel was pissed at his CO. He got busted to corporal.

The army's departure from Saxony was met with more regret than relief by the Saxon merchant class. Not only were all those solders leaving, taking with them their monthly pay, but Third Division took with it the best access to the new goods they'd had since, well, ever.

Near Zielona Góra

David listened as General Stearns asked him to develop a way to magically supply the Third Division with even less of a logistics train than they had had in Saxony. He stared at the table, not seeing it at all. Instead he was seeing a spread sheet of consumables that they didn't have and what his business contacts had told him might be bought in the area around Zielona Góra

"Pretty tricky, sir," he said after he'd gone over the charts in his head. "There's no chance of using TacRail like we did in the Luebeck campaign?"

The general shook his head. "We're not fighting French and Danes here, Lieutenant Bartley. Leaving aside his own cavalry, Koniecpolski's got several thousand Cossacks under his command. They're probably the best mounted raiders in Eurasia, except for possibly the Tatars. TacRail units would get eaten alive before they'd laid more than a few miles of track, unless we detailed half our battalions to guard them. Which we can't afford to do."

David nodded. He'd been expecting the answer. And he knew darn well that the locals wouldn't be taking chits. Not here, not even at sword point. It would take guns, lots of them, and dead bodies for demonstrations. Not something the general would sanction, thank God. And not something that David would do even under direct orders. This would require thinking outside the box. "That leaves what you might call creative financing."

"That's what I figured—and it's why I called you in."

Yep, that was just going to thrill the shit out of Colonel McAdam. "The regular quartermasters are already kinda mad at me, sir. If I—"

"Don't worry about it. To begin with, I'm pulling you out of the quartermaster corps altogether. You'll be in charge of a new unit which I'm calling the Exchange Corps."

"Exchange? Exchange what, exactly?" David looked at the general carefully and got back a grin that was more than a little scary. Suddenly David remembered that the general used to be a prizefighter.

"That's for you to figure out," the general said, still with that "I'm going to enjoy ripping your arms off" grin. "Whatever you can come up with that'll enable us to obtain supplies from the locals without completely pissing them off. No way not to piss them off at all, of course. But the Poles have had as much experience with war over the last thirty years as the Germans. They'll take things philosophically enough as long we aren't killing and raping and burning and taking so much that people die over the winter."

David went back to starring at the charts in his head. Personally, he doubted that the locals were quite as sanguine about having their crops stolen for pieces of worthless paper as the Prince of Germany thought they were. He was going to have to come up with some way of getting goods, manufactured goods, through. Enough to create the belief that the pieces of paper weren't worthless. Maybe steam barges up the Oder. "Okay," he said eventually. "I've got some ideas. But I'll need a staff, General. Not too big. Just maybe three or four clerks and, ah, one sort of specialist. His name's Sergeant Beckmann. Well, Corporal Beckmann, now. I got him his stripe back but then he ran afoul of—well, never mind the details—and got busted back to corporal."

"Where is he now? And what sort of specialist is he?"

"He's right here in the Third Division, sir. One of the quartermasters in von Taupadel's brigade. As for his specialty . . . Well, basically he's a really talented swindler."

"Okay, you got him—and we'll give the man back his sergeant's stripe. May as well, since I'm promoting you to captain."

David felt himself smiling. It was silly and he knew it, but little nerd boy was going to be a captain in the army. Yes, he was a millionaire, but that wasn't the sort of status that had mattered before the Ring of Fire. Before the Ring of Fire, his world had been a world of tough kids and kids who got picked on. David had been among the kids that got picked on. His world hadn't had millionaires in it, but it had had army people and an army captain wasn't in the picked on category.

Zielona Góra

He was less happy a few days later after Zielona Góra had been taken. David Bartley hated sitting on his ass. It was a discovery he had made recently, not having had much opportunity to do so since he was fourteen and the Ring of Fire happened. But of the "hurry up and wait" of the army, it was the "wait" part that bothered him more than the "hurry up" part.

Luckily, there were things to do. David headed for the radio shack. He needed some help figuring out how to create a market out of nothing. And he needed to set up some kind of legal framework for the Exchange Corps.

There was suddenly a lot to do.

The sprinkling rain on the way to the radio shack didn't bother him at all.

Yet.

He sent messages off to Magdeburg, Grantville and Badenburg. He had cleared the structure of the Exchange Corps as a stock corporation with the general and rumors about it had started almost immediately. That was probably Johan's work. Troopers in the division wanted to buy in. So he had investors before he had a company or any but the most basic notion of what sort of company to build. He sought advice from older, wiser heads in the business community that had migrated to the Ring of Fire area in the last few years. He sent more messages to Magdeburg, instructing his agents to set up the Third Division Exchange Corps as a corporation.

****

"All right, Captain Bartley, tell me about the Third Division Exchange Corps Corporation," Colonel McAdam said.

"General Stearns ordered me to set up an Exchange Corps before we took Zielona Góra, sir," David said. The colonel just looked at him. David continued, "Forming it up as a corporation gives people confidence in it. It's listed on the Magdeburg and Grantville Exchanges. The price of its stock is reported with the stock reports on the radio and in the newspapers. It's not going to march through, steal your stuff, and be gone. So people will be willing to wait a bit for the goods to arrive. We can buy grain and wine . . . they make a decent white here, sir . . . or they will, once they get in some equipment. And pay them in contracts for the equipment they need to set up industries."

"Like you did in Saxony but with less equipment to start with? And you're doing this on your own like you did in Saxony, too?"

"No, sir. That's another reason for the corporation. The troops in Third Division will be able to buy in to the Third Division Exchange Corps by filling out a form and having a percentage of their monthly pay set aside for it, just like they can buy insurance. That's so that the men will have an interest, but also because we need the money. And a few bucks a month from four thousand men is a lot of money."

"Four thousand?"

"I was being a bit conservative. I figure we have a good chance of getting half the men to put up ten to twenty bucks a month, depending on their personal circumstances and attitudes. Call it four thousand men and ten bucks apiece, that’s forty thousand bucks a month to buy goods manufactured along the Elbe and ship them here. Zielona Góra is a mostly a trade town, a bit of wine, like I said, but mostly trade. So far the Thirty Years' War hasn't treated it very kindly. But now that it's back in the USE, heck, even if it was in Poland it would be near the border, so it makes a pretty good conduit for trade between the USE and Poland."

"We're unlikely to be here long enough to do that."

"Yes, sir, but we can set it in motion. And Third Division has wounded who need new employment. Especially in the Hangman. They took a beating."

Colonel McAdam and the Division's S4 bought several thousand shares and Brigadier Schuster and the 2nd Brigade bought even more.

****

"You told me three weeks ago that it would be here in ten days!"

David looked up from his work and wished he hadn't. "Come now, mein Herr. You know as well as I do that rain, this kind of rain anyway, causes delays,"

"Ten days! This is twenty-one! I want my parts or I want my money!"

"Fine. I will instruct the cashier to return your money, including the membership fee. When the goods arrive, they will be sold to someone else. Someone not quite so discomforted by the standard delays involved in shipping goods through a war zone in the middle of winter."

"I didn't say . . ." Herr Kopenskii ran out of steam as he realized that yes he had said. "I didn't mean . . ." Again the pause. David knew what he'd meant. Partly it was just the standard "let's see what I can get out of the delay" that David suspected would be going on in any time and place where people did business. But in this case, that was only part of it. Everyone knew by now that the king and been injured and that for now Wettin and Oxenstierna were running things. What would happen to his investment if the USE abandoned Zielona Góra and he was left with a receipt for goods that would never arrive. Herr Kopenskii had taken a considerable chance on Mike Stearns reputation and, for that matter, David's.

The Prince of Germany and David Bartley had said there would be a permanent Third Division Exchange Club Store in Zielona Góra, and that goods ordered would be delivered, but what if Third Division was ordered out of Zielona Góra? What if Zielona Góra was given back to Poland?

"The Exchange Club will remain even if Zielona Góra is yielded back to Poland," David said with confidence he wished he felt more strongly. The store was a golden-egg-laying goose for whoever owned Zielona Góra, because it provided a way to get industrial goods to the western edge of Poland or the eastern edge of Germany at something approaching a reasonable price. But David had seen too many golden-egg-laying geese turned into pâté de foie gras by stupid nobles, and if Poland hadn't cornered the market on stupid nobles, it was certainly a major supplier. Still, the odds were that the USE would keep Zielona Góra, at least for a while. "Captain von Baruth will be staying on to manage the store, even if the division is transferred."

Captain Eric von Baruth was a member of the Hangman Regiment who was wounded in the taking of Zielona Góra. He also was a college-educated son of the lower nobility who spoke German, Polish, French, English, Latin and Amideutsch. Which made him acceptable to the local merchant community. He was a member of the CoC, which made him acceptable to the Third Division 's more radical elements. He was very good with figures and a competent organizer. Which made him acceptable to David. He was also missing one leg from the calf down, which was why he was quite pleased to be offered the job of managing the Exchange Corps Superstore in Zielona Góra.

It took some more cajoling but David sent Herr Kopenskii on his way, if not happy at least not hollering fraud.

****

Sergeant—at least for now—Beckmann snorted as he watched Herr Kopenskii leave. Beckmann would have taken his money back if he'd been in Kopenskii's shoes. The risk was too great for the gain. Then he looked at Captain Bartley. Well, maybe not. Bartley had what Beckmann thought of as an impractical streak. Still, the lad made it work for him and his man Johan Kipper was pragmatic enough to give you nightmares if it came down to it. Beckmann cleared his throat. "Radio messages, sir."

The captain gave Beckmann a half smile and started reading through them. Beckmann had already read them, of course. The Third Division Exchange Corps Corporation was now an officially registered corporation on the Magdeburg and Grantville exchanges. Ownership was two million shares, a half million of which were held as reserve by the Third Division. A million of which were available to sell to members of the Third Division. And half a million of which would be sold on the various stock exchanges to raise capital. The prospectus listed it as a wholesaler of manufactured goods with outlets to be established. The outlet in Zielona Góra had been established in advance of actual establishment of the corporation.

All of which was beside the point because the next radio message was a "for your information" that Third Division had been ordered to Prague to support "our ally, King Venceslas V Adalbertus of Bohemia."

Beckmann knew this news was not that bad. Not in and of itself. They would have to do some setting up but they could handle it. But moving meant more set-up expenses and the Division was broke. Captain Bartley called it a cash flow problem and insisted that nothing the size of a division was ever really broke. But to Beckmann the Division was broke. Oh, the men would still get their pay and ammunition, and other goods would still arrive.

Beckmann shook his head at the weirdness of up-timers. How the same hard-ass officer who had men shot for getting a bit rowdy could turn around and pay for the rebuilding of Zielona Góra, a town that had gotten itself shot up fighting his division, made no sense to Beckmann

Meanwhile, the Division's discretionary funds were pretty much tapped out and start-up funds for the Exchange Corps weren't there.

****

Adolph looked at the note that had been hand-delivered to him. It was from Herr Krupt, who was David Bartley's agent in Magdeburg. "Herr Bartley would be most grateful if you could see your way clear to providing him with six eight-horse power steam engines for the use of Third Division Exchange Corps."

"I won't do it. I don't care if he did back me." Adolph's face was a bit more florid than usual, he could feel it.

"Ah, the Bartley kid strikes again." Heidi Partow grinned. "He's a sneaky little shit, I grant you. I figured he was a waste of space up till the Ring of Fire. Even after it. I still can't figure out what he does. If he actually does anything. It was my little brothers who designed the sewing machine making machines, you know." Heidi crossed her eyes like she was looking at the sentence she'd just said and not liking what she saw.

Adolph couldn't help but grin at her expression. Then his smile faded. "He manages," Adolph said. "And he's darned good at it. And, yes, I do know that your brothers developed the machines to make the parts of the sewing machines. I know because David told me so every time the subject came up. And if you think he was irritating as your little brother's friend, how do you think you would have liked having him as your stepbrother?" Adolph sighed. "Still, I'd like to help him out because, well, when I needed the money to start this place, he's where I got it. And because it's the Prince's Division."

"Mike Stearns is not a prince," Heidi said in a firm, almost belligerent, voice. "He's just a politician. He works for us, not the other way around." Then she relented. "Still Third Division is our division in a way. It's got lots of CoC, even more than the others. And Jeff Higgins and . . . well, it's sort of ours. I'd like to help. But we're already running three shifts and we can't expand production till we get the new machines."

"And we have customers that paid in advance and expect their steam engines on time. I know."

"Look, we have a lot of the booklets on making steam engines out of wood and leather. Granted, they aren't as good as our real steam engines but they're something."

"Yes, they are. But it's as much the boilers as the engines and a pot boiler is orders of magnitude less efficient." Adolph held up his hand. "I know, and we will send him a crate of the booklets. And I'll talk to the staff and see if we can squeeze out a couple of extra boilers for the Third."

"And as much of a CoC shop as this is, they'll try. But we're already squeezing as hard as we can."

Which wasn't true. Adolph's shops ran three overlapping nine-hour shifts a day and his crews worked alternating three- and four-day weeks. Giving them plenty of time for goofing off or, more commonly, agitating for the CoC.

"It's not the people. It's the machines that are the holdup. We just don't have enough of them." And that was true.

Still, they tried and managed to squeeze out a few extra engines. They weren't the only ones.

****

State Senator Karl Schmidt of the State of Thuringia Franconia glanced over the radio message and made a quick note on it, telling his eldest daughter to handle the matter. The senator was a busy man. Busy with the people's business certainly, but, truthfully, more busy with his own. Being state senator was more a position of status than of work. His work was the running of the Higgins Sewing Machine Corporation and its various subsidiaries. Business was good. Like his son, of whom he was increasingly—if still secretly—proud, he was running three shifts. Of course, he'd been doing that almost since he'd bought out the company back in '31.

The radio message was from his stepson David. A request for goods to be sold to the Third Division Exchange Corps. Karl was better positioned and by now had a bit more slack. He could send more sewing machines and more electroplated flatware and, well, generally more. Not that he handled that himself. He turned it over to his eldest daughter, who had taken over for Adolph after the boy had run off to start his own business. Gertrude would handle the matter.

The second radio message was more serious. He wished Uriel Abrabanel still lived here. He would know what to do. Karl didn't. Karl was among the most conservative of the Fourth of July Party and had considerable sympathy for William Wettin's positions. To be honest, Mike Stearns scared him and he had almost followed Quentin Underwood to the Crown Loyalists; would have if it hadn't looked like he would lose his senate seat if he did. Not that any of that mattered. The important point to Karl Schmidt was that his stepson was in the Third Division and in charge of the Third Division Exchange Corps. Which meant that Third Division's financial problems would reflect badly on the family and there were blood ties involved. He didn't have any answers for David, but he sent back that he would help if he could.

****

There were other messages; to the Board of Directors of OPM, to the presidents and owners of companies financed by OPM. Generators, power tools, nuts, bolts, plow blades, knives, ax heads, and more got diverted to the Third Division Exchange Corps warehouses while they were still not sure where they would be shipped. All while David Bartley didn't know where he would get the money to pay for them.

Then there were the requests for help from the finance community. Because, though David didn't have any real idea what the answer might be, he did think it would be in the area of finance and economics.

"So, how do you finance an army when the government isn't going to pay it?" someone asked.

"Well, the obvious answer is to borrow the money. And the government may eventually pay the bills, though I would disallow some of the expenses General Stearns has claimed," said Fredric Brum.

The questioner just looked at him. "You think Mike Stearns is cooking the books?"

"No, of course not. I simply think he is being over-generous with the government's money in compensating the victims of war." Then he sniffed. "Not that it makes any difference. All the government will do is pay the bills with IOUs." Brum believed that gold and silver were money and nothing else was. He was a good mathematician and learning to be a good programmer and socially quite liberal. But he stayed up nights worrying about what was going to happen when people finally realized that the vaunted American dollar was just a piece of paper with I owe you another piece of paperwritten on it in fancier wording. Everyone in the statistics department of the treasury knew that.

"Shh, Herr Brum. Someone might hear you. The problem with borrowing money is that with the way things are right now, a lot of the big lenders would be afraid of how the government would react. They could issue preferred stock, I guess."

****

"Say, Fonzie," David said as he entered the tent.

Frenczil Becker gritted his teeth theatrically and David grinned. Frenczil (the Fonz) Becker sported a black leather jacket, used goop on his hair, and put on tough-guy airs. Not, David would freely admit, without some justification. The Fonz was a lawyer who had joined the Third and become the executive officer of a rifle company. He had distinguished himself in combat and was respected by your average CoC tough. With the formation of the Exchange Corps, he had been seconded to it part-time. That is, in addition to his other duties. He had, in fact, been the one who drew up the actual papers of incorporation that had been signed by General Stearns.

"What do you know," David continued, "about the laws and penalties involved in issuing money or money-like stuff."

"What laws and penalties?"

"Well, someone at the treasury suggested we issue preferred stock and sell it locally but I'm afraid that might be too close to issuing money, so I wanted to find out about the applicable laws."

"And again I ask 'what laws'? There was some talk of making it illegal to issue money, but it would have stepped on too many toes. Rights granted in perpetuity to towns and nobles. It was hard enough to get them to swallow that their taxes had to be paid in USE dollars."

"You mean the Exchange Corps could just issue money?"

"Sure, but who would take it?"

David turned around and left the tent shaking his head. This would require thinking about. He had known that towns and cities were still issuing their own money, that John George and Georg Wilhelm had both issued paper money that had never been worth much, but he had assumed that they had special permission, or been grandfathered in. Mostly he'd ignored the matter, insisting on doing business in American dollars. Which was getting to be a pretty standard clause in contracts in the USE these days.

****

"Run that by me again, Lieutenant." Jeff Higgins shook his head. "I'm having some trouble with the logic involved."

David managed to hide his irritation at Colonel Higgins' forgetting his new rank yet again. He knew Jeff didn't mean anything by it. What was more difficult was trying to explain money matters to someone as ignorant of them as most people were "Well . . ."

He sat up straighter on the stool in a corner of the Hangman Regiment's HQ tent. "Let's try it this way. The key to the whole thing is the new scrip. What I'm calling the divisional scrip."

Higgins shook his head again. "Yeah, I got that. But that's also right where my brain goes blank on account of my jaw hits the floor so hard. If I've got this right, you are seriously proposing to issue currency in the name of the Third Division?"

"Exactly!" David said, without adding that they had been doing essentially the same thing every time they had issued a chit. "We'll probably need to come up with some sort of clever name for it, though. 'Scrip' sounds, well, like scrip."

"Worthless paper, in other words," provided Thorsten Engler. He, like Bartley and Colonel Higgins himself, was also sitting on a stool in the tent. The flying artillery captain was smiling. Unlike Jeff, he found Bartley's unorthodox notions to be quite entertaining.

"Except it won't be—which is why we shouldn't call it 'scrip.'"

"Why won't it be worthless?" asked Major Reinhold Fruehauf.

That question caught David up short because it was so basic and because he didn't have a clue how to explain to the major how money, all money, not just the Division scrip, got its value. The major was leaning casually against a tent pole. He was a good man and reasonably intelligent, but what gave money its value was an imponderable. "Why won't it be worthless? Because . . . Well, because it'll officially be worth something." Which was ridiculous, but explaining that "it would have value because it was perceived to have value, and being perceived to have value, it would buy stuff, which in turn would give it real value" was a bit beyond David's ability to articulate just at the moment.

The regiment's other battalion commander cocked a skeptical eyebrow. "According to who, Captain? You? Or even the regiment itself?" Major Baldwin Eisenhauer had a truly magnificent sneer. "Ha! Try convincing a farmer of that!"

"He's right, I'm afraid," said Thorsten. His face had a sympathetic expression, though, instead of a sneer. Engler intended to become a psychologist after the war; Major Eisenhauer's ambition was to found a brewery. Their personalities reflected the difference.

"I was once one myself," Engler continued. "There is simply no way that a level-headed farmer is going to view your scrip—call it whatever you will—as anything other than the usual 'promissory notes' that foraging troops hand out when they aren't just plundering openly. That is to say, not good for anything except wiping your ass."

David looked at them, totally lost in trying to explain that those level-headed farmers who would never accept scrip had been happily trading their grain for scrip since before Caesar was a pup. Scrip made out of metal not paper, granted. But that only made it scrip that wasn't even good for wiping your ass with. "But—but— " but how to explain to these good men who knew the world was flat and the sun went around it on a crystal sphere that the world was round and went rolling around the sun. "Of course, it'll be worth something. We'll get it listed as one of the currencies traded on the Grantville and Magdeburg money exchanges. If Mike—uh, General Stearns—calls in some favors, he'll even avoid having it discounted too much." He squared his slender shoulders. "I remind all of you that they don't call him the 'Prince of Germany' for no reason. I can pretty much guarantee that even without any special effort, money printed and issued by Mike Stearns will trade at a better value than a lot of European currencies."

Now, it was the turn of the other officers in the tent to look befuddled. As well they should. They knew as well as David did that the Saxon thaler—which until this spring was supposedly backed by silver—was worth bupkis compared to the American dollar that was paper backed by nothing but "I said so."

"Can he even do that?" asked Captain Theobold Auerbach. He was the commander of the artillery battery that had been transferred to Jeff's unit from the Freiheit Regiment.

Bartley scratched his head. "Well . . . It's kind of complicated, Theo. First, there's no law on the books that prevents him from doing it."

Auerbach frowned. "I thought the dollar—"

But David was already shaking his head. "No, that's a common misconception. The dollar is issued by the USE and is recognized as its legal tender, sure enough. But no law has ever been passed that makes it the nation's exclusive currency." The people who had the traditional right to mint money would never have stood for it.

"Ah! I hadn't realized that," said Thorsten. The slight frown on his face vanished. "There's no problem then, from a legal standpoint, unless the prime minister or General Torstensson tells him he can't do it. But I don't see any reason to even mention it to anyone outside the division yet. Right now, we're just dealing with our own logistical needs."

The expressions on the faces of all the down-timers in the tent mirrored Engler's. But Jeff Higgins was still frowning.

"I don't get it. You mean to tell me the USE allows any currency to be used within its borders?"

He seemed quite aggrieved, David noted with a grin.

"You're like most up-timers," David said, "especially ones who don't know much history. The situation we have now is no different from what it was for the first seventy-five years or so of the United States—our old one, back in America. There was an official United States currency—the dollar, of course—but the main currency used by most Americans was the Spanish real. The name 'dollar' itself comes from the Spanish dollar, a coin that was worth eight reales. It wasn't until the Civil War that the U.S. dollar was made the only legal currency."

"I'll be damned," said Jeff. "I didn't know that."

He wasn't in the least bit discomfited. As was true for most Americans, being charged with historical ignorance was like sprinkling water on a duck.

Colonel Higgins stood and stretched. "What you're saying, in other words, is that there's technically no reason—legal reason, I mean—that the Third Division couldn't issue its own currency."

"That's right." Well it was right as far as it went, which wasn't very far.

A frown was back on Captain Auerbach's face. "I can't think of any army that's ever done so, though."

David didn't say what do you think the chits we've been passing out are? It wouldn't do any good. "So? We're doing lots of new things."

"Let's take it to the general," said Jeff, heading for the tent flap. "We haven't got much time, since he's planning to resume the march tomorrow."

****

General Stearns was charmed by the idea. "Sure, let's do it. D'you need me to leave one of the printing presses behind?"

"Probably a good idea, sir." David said. "I can afford to buy one easily enough. The problem is that I don't know what's available in the area, and we're familiar with the ones the division brought along."

"Done. Anything else you need?"

David and Jeff looked at each other. Then Jeff said: "Well, we need a name for the currency. We don't want to call it scrip, of course."

Mike scowled. "Company scrip" was pretty much a profane term among West Virginia coal miners.

"No, we sure as hell don't," he said forcefully. He scratched his chin for a few seconds, and then smiled.

"Let's call it a 'becky,'" he said. "Third Division beckies."

****

Sergeant Beckmann was seated at a little folding table in their room of the castle. "Not to get all philosophical or anything, sir, but what is money?"

Johan Kipper groaned and David grinned. "Be thankful you didn't ask that of one of the economists at the Fed or Treasury. Best I've been able to tell from their lectures on the subject is that it's just IOUs."

"Of course, if you say that to one of them," Johan said, "they'll spend hours telling you that it's not just IOUs, but takes on the demonic aspect of IOUs, not the angelic aspect or vice versa. And that in its true platonic form, money is a store of wealth . . ."

"Now, now, Johan. Sarah isn't that bad," David said with a lack of confidence that even he could hear in his own voice.

"IOUs?" Sergeant Beckmann asked. "I owe you whats?"

"That's the tricky part," David acknowledged. "Money has quantity but not form, not kind. It's an IOU for a given amount of wealth of no specific nature. The nature of the wealth gets determined when you buy something with it. And not just the nature, but the quantity, too. The IOU has a quantity on it but what that quantity is worth in terms of actual goods gets determined by what you can and what you can't buy with it. Which is determined by what the person you're trading it to thinks they can trade it for and on and on ad infinitum."

"See?" Johan said. "Angels dancing on the head of a pin."

David snorted but nodded.

"So we issue money IOUs and pass them around to trade stuff?"

"Yes."

"Sounds like a great way to make a living." Sergeant Beckmann grinned like the unrepentant conman he was. "What's the catch?"

"Normally, the catch is getting people to accept the money," David said. "In the up-time timeline the transition from gold and silver to paper took centuries and there were still people that had little caches of gold and silver coins when the Ring of Fire happened. In the new timeline, people right around the Ring of Fire accepted our money at first because we were a miracle. Even if people like General Stearns don't much like acknowledging it. But it was also because we had stuff to sell and our money bought it. How much of that first acceptance was God and how much was goods we may never know, but we had both.

"General Stearns has an international reputation and if the Prince of Germany decides to issue money, a lot of people will accept it. Why not? If the count of nowhere important can issue money, why can't the Prince of Germany?"

David looked around the room and saw that Sergeant Beckmann was nodding but Johan Kipper wasn't.

"Some of it was God right enough," Johan said, "but more of it was goods. Yes, the merchants and craftsmen we dealt with in those first days were willing to cut us some slack because you were up-timers and they didn't want to piss off whoever had sent you here. But mostly it was that they knew that the American dollars would spend in the Ring of Fire and having American dollars to spend made great excuse to go into the Ring of Fire and see the television video tapes and other wonders they'd heard about."

David nodded. "So they took them and found that they could spend them at home because their neighbors felt the same way. We have the reputation, the 'Prince of Germany.' More widespread now, if less holy. The problem is, we don't have the stuff to sell. There's sort of a critical mass that money has to reach before it works and I'm not sure the Prince of Germany gets there all by himself."

"We own that property in Zielona Góra," Sergeant Beckmann said.

"Yes, but it's in Zielona Góra," David said. "Sure, it will start providing us some income once the set costs are paid, but it's a long way away for the people around here to get to."

Sergeant Beckmann hesitated then shook his head and asked, "How long are we going to be here?"

"I don't know, but probably some months," David said. He was pretty sure that the sergeant had been about to ask about diverting the goods for Zielona Góra to here then stopped himself. He was learning. "I think we were sent here to get the Third Division out of the way now that the Crown Loyalists have control of the government. So it could be years. Until the next election." Then David realized the import behind the question. "Sergeant, we are probably going to be sitting right here when the people we have bought stuff from using the beckies come into town to buy stuff using the beckies and we had better have stuff to sell them. Even if we weren't going to be here, leaving the people in this region holding a bunch of worthless paper isn't something the general would sanction, nor something I'd do even under direct orders.

"Yes, sir!" Sergeant Beckmann said, sounding quite sincere. He was really good at that, David noted. "I never thought of doing anything like that, sir. My question was more along a different line. We were just getting started setting up shop in Poland when we got sent here. I was only wondering if we'd have time to set up here and get things running before we got ordered off to somewhere else."

"That's a point, Master David," Johan Kipper said. "The prince, he moves fast for a general, that he does. We probably need to move pretty fast ourselves, in case we need to move before we expect."

David nodded. "All right. Let's get in touch with the king's financial people, since he probably owns this place, and see if we can buy it. Johan, you do that. You're still on the boards of HSMC and half a dozen other Grantville firms. If we can't buy it, find out what we can buy in the area. We're going to need a store to go with the catalog sales. Meanwhile, if we're going to issue beckies, they ought to have a picture of Rebecca Stearns on them. See if you fellows can find a picture of her. I guess we'll have to send to Grantville and have one of the machine shops cut us some plates."

"I think . . . there may be another way," said Sergeant Beckmann. "There's a wood carver with the printing group who makes woodcuts on the side, prints them up for the men. He calls them centerfolds. I don't know why."

David knew why and so did Johan.

Johan muttered, "He'd better not have a centerfold of Becky Stearns or I don't want to be anywhere near him when the general finds out."

The sergeant mumbled something about, "Well, maybe the one of Rebecca Stearns is a pinup, not a centerfold. I'm not really sure what the difference is. Sometimes the guy calls them one, sometimes he calls them the other. Centerfolds and celebrity pinups. He has maybe ten of the celebrity pinups and twenty centerfolds. He runs a little business on the side."

Which was something that Sergeant Beckmann would naturally be familiar with. "Two things, Sergeant. There are laws . . ." David stopped. There were laws up-time and even up-time, if he was remembering right, pictures of celebrities were all over the place, Whether the celebrities wanted them there or not. And Rebecca Abrabanel had had her own TV show. For all David knew this artist of Sergeant Beckmann's acquaintance wasn't doing anything wrong. And if he was, probably the worst crime they could get him on was misuse of Third Division property. "Never mind. Find your artistic friend and bring him here with all his plates. Not just of Rebecca, all of them.

****

As it turned out David's fears were mostly groundless. The naked ladies sold better in the army, but the crew of that printing press sold what might be called celebrity portraits, including Mike and Rebecca, Princess Kristina and Gustav Adolph. Most of which were fairly modest. They also sold some nudes. Miss November of 1992 was quite popular. So were pictures from up-time, the Statue of Liberty, the Eiffel Tower, and others. They carried the plates with the press and had a few prints to show around. When someone wanted one, they printed it up using the printing press and supplies. They also had a pantograph and other tools.

The picture of Becky was from her talk show in 1631. David remembered the show. He thought he might even remember the particular show. It was one where she was talking about how electric circuits worked and how dangerous they could be. But she was standing up and tracing a circuit so she had one arm up. And she was looking out of the picture with that serious, caring expression of hers. David told the guy to use the picture of Becky and maybe the Statue of Liberty.

David was figuring the picture of Becky on the front of the bill and the picture of the Statue of Liberty on the back, but he didn't specify that. The bills were to be four up-timer standard inches by eleven standard inches. Mainly because at the moment they didn't have the equipment to make the detailed plates they would have preferred. And because they were going to need to print assurances on the bills. At least David thought they would. Unlike the American money, they would all have the same images on them, no matter the denomination.

David got busy with other things, mostly having to do with getting the becky recognized as money on the currency exchanges in Grantville, Magdeburg, Venice, and Amsterdam. Well, Prague too. Nobody much outside Bohemia cared all that much about the Prague exchange, but Third Division was stationed in Bohemia just at the moment. David was pretty successful in the important places, but there were political complications in Prague.

By the time he got back to the actual currency, it was way past too late to change anything. The image went long-ways. Becky was ten inches tall from the top of the torch she was holding aloft to the bottom of her gown. The gown was green but the face and arms were flesh tone. The hair was black and the headdress was golden as though her head was surrounded with a halo of golden flames. It was a work of art, especially since it had been done in just a week, from disparate parts of other images.

And David Bartley had the sudden conviction that Rebecca Stearns was never going to forgive him for it. The general would probably like it, and if David knew Francisco Nasi—and he did—the financer/spy would be too busy laughing to take offence. But Rebecca herself? Well, David had only met her a few times but he had the impression of a basically private person. One who only ended up on the public stage when forced there. These, in their hundreds and thousands, would force her there in a way both more widespread and permanent than anything else he could think of.

If the beckies lasted as a currency—and David was really starting to think that they might—then a dark-haired Jewish girl was about to become the embodiment of the German spirit. As soon as possible, David was going to send to Grantville and have one of the machine shops make up some good steel engraving plates with all the little curlicues that make forging more difficult. But they would use these as the model. And start collecting them up as the new ones came online. In the meantime, they used a four-step process of offset printing to print the bills and each bill was numbered. The bills would be forgeable, but not easily.

****

"Captain Bartley. How did you get the contract for the winter uniforms for Third Division?"

"It's complicated, Lieutenant Kappel."

"It's an official request for information, Captain. I have to ask."

David held up his hand. "I know, Lieutenant. Basically I agreed to take payment partially in beckies."

"Beckies, sir!" Lieutenant Kappel's voice squeaked a bit.

"You know and I know that since the change of governments a number of the army contracts have been shifted to the politically-connected sweat shops down near Hamburg."

"I wouldn't call them sweat shops . . ."

David looked at him. They were sweat shops worse than anything David had ever even heard of before the Ring of Fire. Though, according to the historians, not as bad as some in the nineteenth century had been in the old time line. Kappel's face got a little red and David snorted. "Kids working twelve and fourteen hour days in close quarters with bad air constitutes sweat shops in my book, Lieutenant. Also in the general's and, I'd wager a lot, in the emperor's. I know that they are trying to compete with the up-time produced equipment, but frankly that excuse doesn't impress me at all." David shrugged and got back to the point. "Anyway, to overcome the political influence of the self-styled Crown Loyalists, I had to make a bid that would really show the bias if it was rejected. Selling under cost would do it, but I'm not the sole owner of the business. Besides, that would be cheating."

"There are legitimate suppliers out there, sir."

"Yes, there are quite a few of them and they are mostly booked solid, which is why the sweat shops are still in business. Also, most of them will insist on American dollars. Like I told you, I'm taking partial payment in beckies.

"Ten thousand winter uniforms in five sizes," David continued. "One pair of pants, two shirts, one set long underwear, one buff coat, one pair gloves, one pair mittens, one winter cap. One hundred dollars and one hundred fifty beckies per uniform set. Total order, one million dollars and one point five million beckies. Which, if this works, ought to be worth about one point four million American dollars, and if it doesn't will be worth bupkis. Some of my suppliers will take beckies on my say so, some won't. If this doesn't work, I'm going to be out about a million bucks. But that doesn't worry me. Do you want to know what does worry me, Lieutenant?"

There was a noticeable hesitation before the lieutenant nodded.

"What worries me, Lieutenant, is that the whole economic boom is based on faith in up-timer money and if that faith should be lost . . ." David shook his head. "Now, isn't that a thought to take to your dreams?

"Anyway, I offered to take more than half the price in beckies. The nobles and muckity-mucks that have been issuing their own money all along want 'their friends' to take their money as partial payment. Their friends, the sweatshop owners, say not no, but hell no! Now the muckity-mucks are pissed and we get the contract. Understand, Lieutenant, this was all happening very fast while most of the legislature was in Berlin and the clerks who actually run things were trying to figure out which way to jump. While they were getting conflicting instructions from various people within Wettin's coalition. Anyway, shortly after they gave our company the contract, someone in the procurement office notices that they don't actually have any beckies."

By now the lieutenant's eyes were wide. "What happened?"

"They sent General Stearns a message asking for, well, demanding, really, one point five million beckies." David grinned again. "The general, who is in Prague and kind of busy, forwarded it to me. Who sent back a message saying that the Third Division would trade them beckies for USE dollars at a one-to-one basis. And that, Lieutenant, is when you got ordered here to investigate my morals and upbringing."

"So the beckies were simply a scam to get the contract in place of bidders who offered lower bids?"

"Who offered a lower bid, Lieutenant?" David asked. "Even counting the beckies at par with the dollar, $250 a uniform set is a fair price. If there was a bid lower than mine I'll wager it was a cost plus bid, with an estimated cost that was smoke and mirrors. Mine was a set price offer. If production costs are higher than estimated we take the hit, not the government. Likewise, if the beckies don't work out, I take the hit not the government. I'm not getting one point five million dollars for beckies. Third Division is. I'm the one holding the beckies."

"So, what are you going to do with them?" Lieutenant Kappel asked. "The beckies, I mean?"

"I'm going to spend them, Lieutenant," David said. "More precisely, I am going to invest them in local businesses. Businesses which need goods that the Exchange Corps Stores can provide."

****

"With the Elbe frozen for the winter, it's actually cheaper to ship from Grantville," Johan said.

"Talk about roundabout," Sergeant Beckmann said. "Upriver to the railhead at Barby, then by train to the Ring of Fire, by road to Zwickau and by mule path the last eighty miles or so to here."

"And ninety percent of the cost and the risk is in the last eighty miles."

"It's not that bad, Master David," Johan said. "The Fresno scrapers can be made by any blacksmith with the help of a carpenter or wagon maker and they have been. Roads have been improving all over Europe, probably even in Spain."

"It's not that bad, Master David," Johan said. "The Fresno scrapers can be made by any blacksmith with the help of a carpenter or wagon maker and they have been. Roads have been improving all over Europe, probably even in Spain."

David raised an eyebrow at the Spain bit, but he knew Johan was right in general. "All right, Johan, eighty percent . . . fifty percent. But only because we aren’t paying the duties and our supply trains are well-guarded."

"There's a fair chance we'll be able to find a road path that takes us all the way."

"I doubt it," David said. "Even a hundred yard gap between sections of good road and we have to switch to mule train. And that's what we'll end up using for the rest of the trip. We can't afford to have wagon trains sitting waiting for the mule trains. Or mule trains waiting for the wagon trains."

"That might be the best solution. I mean if the gap is short. They probably already have the mule trains," Beckman said. "Heck fire, the mule trains are probably the reason for the gaps."

"We'll know soon enough. I have people out scouting scraper routes," Johan said. Road improvements were spotty and trade shifted as this or that string of towns and villages improved, or didn't, their particular stretch of roads. "Scraper routes" were discussed in towns and taverns across Europe and wagons were starting to replace mule trains because they could go faster and carry more.

In the State of Thuringia-Franconia and in Magdeburg Province, roads were up around the quality of 1900 roads in the old timeline. Mostly dirt, but wide enough for two wagons to pass each other and lots of towns had actual paved streets. In Saxony, not so much. The scrapers were there, but their use wasn't, as a rule, encouraged. Right on the border where good roads meant they could get goods in from Thuringia-Franconia, roads were pretty good. The farther you got from the border, the worse they got. But that wasn't consistent. Some little village would pound out a Fresno Scraper and there would be two little farming villages that were suddenly close enough to each other to support one another. The second village would rent the scraper and extend the road to a third village that had two roads leading to a fourth and fifth village. And without noticing they would produce a roundabout route between two towns.

"Find us a route, Johan. For wagons the whole way if you can, for as much of the route as you can. And if you need some troops to encourage the locals to put their scrapers to work, that can be arranged."

The beckies were already in circulation but sluggishly. They were pushed by the Third Division, not pulled by the locals. Money is a bit like rope—it works a whole lot better if it's pulled than if it's pushed. They needed the people in the area to seek out beckies like they would seek out good silver coins.

****

"Radio message from Grantville, sir," Beckman said. "The wagons are on their way. Should be here in a few days."

"Good enough. We'll have the grand opening of the Exchange Corps Superstore at Tetschen next weekend," David said. "That should give us time to get the store stocked. Have the printers print up a bunch of leaflets announcing the grand opening." David stood and proclaimed, "Send out the luring parties."

****

"No, Goodman, we aren’t here to raid your village nor to buy your goods with IOUs on the USE government," the sergeant said in a bored tone. He was with the Hangman Regiment, TDY to the Exchange Corps and by now this was old hat to him. He and his squad had done it yesterday and the day before. They came riding into a village, handed out the advertising flyers and the pamphlets explaining what the Exchange Corps was in the market for. That the Superstore was opening in the castle at Tetschen. And that, no, he really didn't care if the villagers went to the opening or not. "Look here, my good man, I'm with the Hangman Regiment. We don't rape or pillage, we hang them that do. All I'm here for is to deliver the pamphlets. But it's going to be one heck of a party at the grand opening. They've a whole big store full of goods from Grantville. And we're letting all the villages in the area know that it's happening, so there ought to be a lot of folks who come just to see the place. Truth to tell, it's worth the seeing."

"But we have no money, Sergeant," the village elder whined.

The sergeant didn't whack the old man upside the head, though he was a bit tempted. This one had a particularly grating whine. "I'm not surprised," the sergeant said instead. "That’s what this little booklet here is for. The Exchange Corps buys grain and cheese and, well, all those goods listed there. It pays in good beckies that you can spend at the superstore."

"What happens if we don't go?" the old man asked.

"You miss a good party." The sergeant shrugged. "It's all the same to me, Gramps."

****

They came! Mostly out of curiosity but they came.

Jeff Higgins, who had seen real super stores up-time was not impressed. David, whose memory of such places was getting pretty vague by now, was not really impressed. Even the old Grantville hands were less than overwhelmed. But to the villagers around Tetschen who were looking at the first vise-grips and bearing sets, canned apples, and freeze-dried mushrooms they'd ever seen? Looking at wood lathes, stamp presses, plows and even a steam tractor? They were impressed.

Not for sale, that steam tractor. It was the showroom model and you could order one. Which would get there when it got there. On the other hand, there was a guy that gave rides on it, showing all and sundry how it would pull a plow better than a team of eight horses. And do the same for a Fresno scraper.

The not-subtle theme of the whole event, even of the superstore itself, was an advertisement for beckies. How much is a becky worth? Well, twenty of them will buy a pair of vise-grips; it's marked on the shelf where the vise-grips are. One becky will buy a package of twenty two-inch nails. A steam tractor will be your village's if you can come up with 20,000 beckies. Eventually. A first quality wood lathe, 300 beckies. A real angora sweater, 200 beckies. For 400 beckies, you can get a Partow washing machine and wash your clothes in comfort while toning your legs, rather than breaking your back. The prices were also marked in USE dollars and the price in beckies was generally a bit better than in USE dollars. That two hundred becky angora sweater, for instance, cost 215 USE dollars. The twenty-pack of nails was one becky or one dollar.

In spite of the fact that the superstore was poorly stocked by up-timer standards, with many of the shelves having only examples—like the steam tractor, not for sale themselves, just display models of things you could order—they didn't sell out in that first grand opening sale.

No one had any money. More precisely, most of the villages didn't have beckies or USE dollars. And didn't have much of the local currency either. But after the grand opening party, they wanted beckies. Wanted them badly.

Not that they didn't get orders. As it happened the old farmer who had whined his village's poverty in such an irritating voice took one look at the steam tractor and knew his village had to have it. While not nearly as poor as he had whined to the sergeant, his village wasn't rich.

"It's a five percent deposit and payment on delivery, Herr . . . ?"

"Krup." The voice would have shocked the sergeant had he happened to hear it. It wasn't whiny at all it was rather abrupt. "I am the Mayor of Markvartice." Which was perhaps a bit pretentious, but he was a pretentious fellow when he wasn't whining. He was, however, a bright fellow and dedicated to the welfare of his little village. "What about credit? I heard the up-timers give credit."

So they talked credit, interest on the loan and amount down. They talked about how long the waiting list for steam tractors was. And how if you didn't have the money or hadn't arranged credit when the tractor arrived they would sell it to the next person on the list and you would go to the back of the line. Herr Krup left looking for ways to raise beckies. He figured that the village had six months to raise 20,000 beckies and that was going to take work. But they would do it or he would know the reason why.

****

"So how much for a hundred weight of wheat?" the farmer asked.

"If it passes inspection . . ." The price was reasonable, even good after what he'd seen in the superstore. The farmer had paid his rent and tithes in kind just after the harvest and had some wheat left. This wasn't the lean time of year, but it would be coming on fairly soon. Still, if they could get the wood lathe for Karl now during the slack time, they'd have chairs and tables to sell come next harvest.

"We'll be bringing in a few hundred weights then." He went on his way.

****

The next guy wanted to know about the price for cabbage and the one after that for flax. Then hemp and . . .

It was winter, moving toward the lean time, but people had been hearing more and more about the wonders of the up-timers in the years since the Ring of Fire. Most of them had either never seen an up-timer product or had only seen one held as a talisman of better days at some nebulous time in the future. Now in Tetschen there was a store that had up-timerish stuff for sale. It used up-timerish money backed by the most famous up-timer of them all, the Prince of Germany, with a noble portrait of his wife, the famous and beautiful Jewess, Rebecca Stearns neé Abrabanel. A trip to Tetschen wasn't exactly a trip to Grantville, but Tetschen was closer. People came and they brought what they could scrape together and they had one great advantage over the looting parties that an army would send out to supply itself. They knew precisely where the stuff was hidden. After all, they were the ones who had hidden it to keep it safe from the looting parties.

It became much easier for the supply officers of the Third Division to buy stuff with beckies. It wasn't instant. At first it was a very short loop. The goods came in, got turned into beckies and the beckies got spent right there in the Exchange Club Superstore. But there were the people that let it be known that they would do work for beckies because the village was saving up for a tractor or plows or because the family or an individual wanted canning jars, a crystal radio set, a record player or whatever. The loop got a little bigger. Taverns and inns started taking them willingly. Finally the local nobility decided they would accept them as rent. They were money.

****

"He doesn't look a thing like Tony Curtis," Jeff Higgins muttered to himself, remembering a movie he'd seen about a pink submarine. And it was true. David Bartley didn't look a thing like Tony Curtis. Nor was it a casino, but David did have one thing in common with the supply officer played by Tony Curtis. They both sat like spiders in their webs while the supplies came to them.

"There's another difference, Colonel Higgins," a voice said from beside him.

"What? Oh, I didn't see you there, Herr Kipper," Jeff said to the older man.