1

THE WARM FACE OF HISTORY

We learn so much about the knife from history and prehistory that we perhaps take it for granted. Don’t. It dates back to the Stone Age in time, and it is found all over the world. Even cultures too primitive to know and use the wheel have some form of the knife. Such widespread acceptance is pretty amazing when you think about it.

A flint knife made by Greg Phillips.

From the collection of Laura Brayman. Photo by Charlotte Proctor.

It’s also one of the most useful tools man has. You’ll find it not only in the hunter’s camp, but in the kitchen, on the farm, in the garage, the home workshop—even in the artist’s garret.

And every culture that has used it as a tool has also found uses for it as a weapon. A weapon is simply a tool for inflicting injury.

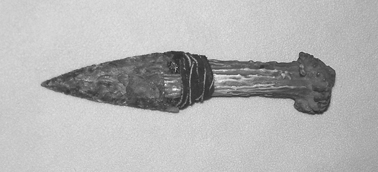

On the surface, the knife is a very simple device. Yet each society developed a knife or knives to its own individual needs and perceptions of what worked best. Thus the Gurkhas adopted and developed the kukri,

Nepalese kukri, 16 inches overall length. HRC545

the Arabs the jambiya,

Arab jambiya, 15 inches overall length. HRC516

the Japanese the tanto.

Japanese tantos are usually 12–14 inches overall length.

Most tribes and many individuals have developed slight variations on the theme of our very simple device.

A good many factors can go into influencing the way a knife can be developed, including available materials and purpose. Over the years, style and fashion have played as important a role in the creation of knives as they have in the creation of clothing: a knife can very easily become a mere decorative accessory. It should also be remembered that knife fighting techniques frequently develop around the type of knife most readily available. Technique does not that often drive design of the knife.

Frankly, there are styles I just don’t understand. One of them is the Ethiopian sword, the shotel,

A shotel.

Illustration by Peter Fuller.

which is a long, deeply curved blade that is sharpened on the inside edge. It is not a chopping weapon like the kukri. Rather, it is used to reach around an opponent’s shield and stick him. Now this is a good trick with a curved sword, but as a fighting style it is marvelously ineffective.1

[There are styles that did work, however, and some of them were recorded for posterity. One manual in particular I have always found useful, as it includes knives as well as swords. The style described in it cannot be called a] modern combat style, but it has captured the essence of the art, and done it very well.

The author of this work was George Silver, an English fencing master who lived in the late sixteenth century. He seems to have been not only a Master of the Sword, but of practically every other edged weapon as well. He had a knack of grasping the capabilities and limitations of various weapons with little or no apparent effort. His book, Paradoxes of Defense, is an excellent assessment of many weapons, and in view of his fame with the sword, it’s interesting that he preached the superiority of the “short sword” over the rapier. This was prophetic, as what he termed the “short sword” became known as the small sword or the dueling sword.

In the quotation below, I have modified the antiquated spelling for the purposes of clarity. But I want you to remember something as you read it. George Silver made his living with a sword, not with books.

First know that to this weapon there be no wards nor grips but move against such a one as if foolhardy and will suffer himself to have a full stab in the face or body to hazard the giving of another, then against him you may use your left hand in throwing him aside, or strike up his heels after you have stabbed him.

In this dagger fight you must use continual motion so that he not be able to put you too close to grips, because your continual motion disappoints him of his true place, and the more fierce he is in running in, the sooner in giving you the place, whereby he is wounded and you not endangered.

The manner of handling your weapon and continual motion is this. Keep out of distance and strike or thrust at his hand, arms, face or body. Press upon him, and if he defends the blow or thrusts with his dagger, make your blow or thrust at his head.

If he comes in with his left leg forwards, or with the right, do you strike at him as soon as it shall be within your reach, remembering to use continual motion in your progression and regression.

Although the dagger fight be thought a very dangerous fight by reason of the shortness and singleness of the weapons, yet the fight being handled as aforementioned is as fast, safe and defensive as any other. Thus endeth my brief instructions.

Street fighting and knives are not generally considered pleasant subjects. They seem to generate a certain distaste and scorn. Oddly enough, this scorn frequently occurs in the sort of people who extol the virtues of Jim Bowie and man-to-man shoot-outs in the Old West. The knife fights of Jim Bowie are the stuff of legends and the man-to-man shoot-outs of the Old West are questioned by many historians. No matter. Those things happened a long time ago.

Street fights with the knife still occur.

Hank’s experimental double-edged fighting knife, 13 inches overall length. HRC43

1Editor’s Note: this is where a page was missing from Hank’s manuscript; his introduction is merged into his first chapter. The transitional material, shown in brackets, was written by Whit Williams.