EDITOR’S NOTE

As with Hank Reinhardt’s Book of Swords, this volume is being published posthumously. In the case of the former, it was because Hank died before putting the final polish on the manuscript he had been working on for two decades. In the case of this book, it was because he felt very ambivalent about making this material public.

Hank studied fighting in all its forms, from wrestling to rhetoric. He was probably the world’s foremost authority on fighting with historical bladed weapons at the time of his death in 2007. But necessarily his understanding of swordplay and use of polearms was from recreation, not actual use in wars or duels. The same cannot be said of his understanding of fighting with knives.

Hank grew up in a large city (Atlanta) in the 1940s and ’50s, and did not lead a life of suburban insulation. As a young man he got into fights, and he got into trouble, and the lessons imparted in this book come from his practical experience, his observations of fights, as well as decades afterward spent sparring, researching and thinking about bladed weapons. He wasn’t precisely ashamed of his experiences, but he also knew they were not the sort of thing a gentleman bragged about, and Hank was always a gentleman. As he says, the best way to win a knife fight is to not be in one, and he certainly didn’t want a book of his to encourage anything otherwise. From Chapter 2: “There has never been anything glamorous or heroic about it. It has always been a quick and dirty business and it always will be.” And Chapter 6: “The real knife fighter does not wish to engage in a fight.”

So he never tried to have the book published in his lifetime. It is for exactly this reason that we think what he had to say is important to the field, and we wanted to share that with more than just his actually rather large circle of friends. You, the reader, know that he has no ax to grind and that he is not trying to sell you seminars, videos, or super secrets of the samurai. He just put down the things about fighting with knives he thought it important to know. Besides, if any of these stories about people Hank knew happen to actually be about Hank, surely the statute of limitations has passed, and they can’t catch him now.

The manuscript itself was written, we think, in the late 1970s, early 1980s. Bill Adams, Hank’s partner at Museum Replicas, Ltd., the ground-breaking sword and bladed weapons catalog, helped Hank get the manuscript professionally typed. Sometime before the typing, an interior page was lost. Sometime in between that time and when Hank passed away in 2007 and I found the manuscript in his files, the first page of the manuscript went missing.

Rather than try to recreate the first page from context, we merged his short introduction with the first chapter. Added transitional material provided by Hank’s student Whit Williams is indicated by brackets. Whit also had the idea of including more of Hank’s students in this book and surveying them about what their best “lesson learned” from Hank was, and these responses are included in the “Interlude” between Parts I and II.

Another of Hank’s students, Greg Phillips, wrote Part II, providing additional material updating the description of knives currently commercially available, and setting down more about Hank’s training and sparring techniques. Greg worked with Hank for forty years learning about the history and performance of edged weapons, modern, medieval, and ancient. And he has been a security guard for decades, sometimes in the course of his duties putting into practice Hank’s teachings. I can attest that he is also a great teacher in his own right.

When I use the word “student,” I mean both those like Mike Stamm who took a formal course with Hank, and others, like Greg and Whit, whom Hank took under his wing and sparred with informally for many years. Hank made no distinction himself. If you were interested in bladed weapons, Hank would be happy to talk to you. (Or if you were interested in science fiction pulp magazines, or Gilbert and Sullivan, or bonsai trees, or WWI airplanes—but his thoughts on those topics will never be written down beyond what is archived at his website, www.hankreinhardt.com.)

Hank at Dragoncon. Photo by Nils Onsager

Hank was a natural teacher. When we first started dating, he decided that since I was an editor of science fiction and fantasy I should know more about realistic fight techniques. Now, I’ve been carrying a knife since I was in first grade, sometimes a simple folder, but more usually a utility knife like a Leatherman or Swiss army multi-tool, so I agreed that my knowledge on fighting with knives could be expanded. He rolled up a piece of paper, handed it to me and told me it was a knife. He made one for himself and called on me to defend myself. Then he promptly gave me a paper cut. (I married him anyway.)

We hope that in this book you will experience something of what it was like talking with Hank and even, to some extent, sparring with him. Many of the illustrations are based on sparring sessions with him that were filmed, and the illustrations of positions and moves taken directly from the videos. Whit Williams, leader of the Reinhardt Legacy Fight Team, a group of men—many of whom were taught by Hank—who demonstrate and teach historical weapons use, and his brother Allen Williams, organized all the illustrations for this volume. Allen also provided the sketches for all of the drawings provided by illustrator Dave Newton. Most of the knives photographed for this volume belonged to Hank.

I can’t say that I never saw Hank without a knife, but I can say that I never saw Hank with his clothes on without a knife. He was not a collector of knives as he was a collector of swords, polearms, kukris, and Indo-Persian arms and armor. He was an accumulator of knives, though, and had somewhere in the range of a hundred of various kinds when he died.

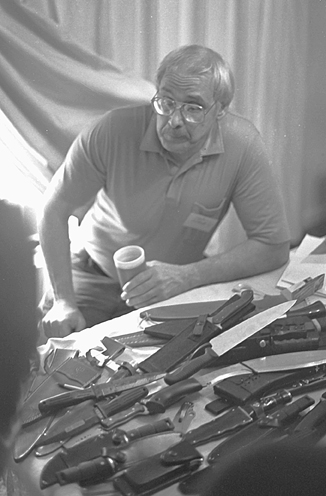

Hank and his knives.

Photo by Richard Garrison

Some are functional works of art, like the Damascus Jimmy Fikes Bowie knife illustrated within, some are historical European daggers, some exotic Eastern push-knives, some anonymous generic folders, some weird hybrids that Hank had worked on himself, including one large fighting knife that he cut down from a Chinese polearm. When Hank didn’t have an example in his collection that was appropriate to illustrate the text, we have borrowed from other sources, like the collection of Patrick Gibbs, and labeled accordingly. Knives that come from Hank’s collection are indicated with “HRC” and a number.

Many people helped out with this book in various capacities, from proof reading to fact checking, including his daughters, Dana Gallagher and Cathy Reinhardt, and his friends: Hilliard Gastfriend, Mike Stamm, Steve and Suzanne Hughes, Jerry & Charlotte Proctor, Greg Phillips, Patrick Gibbs, Peter Fuller, Allen Williams, Nils Onsager, Jimmy Fikes, Steve Shackleford, Mike Janich, Rich Garrison, Happy Heatherly, John Maddox Roberts, Massad Ayoob, artist Dave Newton, and finally the members (and wives & girlfriends) of the Reinhardt Legacy Fight Team (check out reinhardtlegacyfightteam.com for their calendar of demonstrations). This book could not have been produced without the beyond-the-call-of-duty actions of typesetter and book designer Joy Freeman. Of course, the responsibility for any failings in the text or in our attempts to illustrate Hank’s techniques, falls to me, the editor. Please feel free to send comments to me at: toni@baen.com.

—Toni Weisskopf Reinhardt, 2011