“They’re all gross,” Addi said. “Except the turkey tail—it’s sort of cute.”

“They’re all gross,” Addi said. “Except the turkey tail—it’s sort of cute.”7

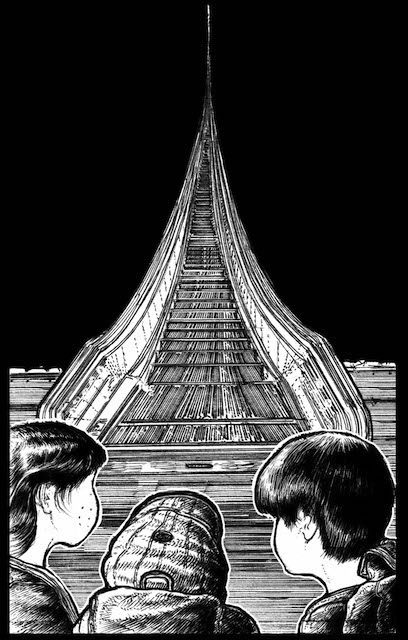

A Hidden Moving Staircase

The Garden Center had a high roof and no outer walls except for curtains of green mesh that buddypards rolled up or down with pretty silver ropes. Joel-Brock, glancing about, took a grateful breath. The Center smelled of pine, mint, and honeysuckle, of gardenias after a good gobbymawler misting.

Addi turned in a wide circle, extending her arms to embrace the sweetness. “This almost makes up for all the gobbymawling Big Box Bonanzas does when they move into town. I mean, they clear out the native plants, all the animals and bugs that rely on them, and then they pour acres of concrete.”

“Not always,” Joel-Brock said.

“Oh, yeah?” Addi said. “Where didn’t they?”

“Here in Cobb Creek. The concrete was already here. Mr. Borsmutch bought an old strip mall, tore its stores down, and built this box on top of them—the very first Big Box Bonanzas in North America.”

“Yeah. That I do know. Every ten minutes, some grinning buddypard tells you, This is the First Store in the Most Successful Discount-House Franchise in the Whole Stinking World.” Addi swung into an animated cheerleading bit: “Who’s Bonanzic? / We’re Bonanzic! / Sis-boom-bah! / What’s Bonanzic? / We’re Bonanzic! / Sis-boom-shush!” She bent, put a finger to her lips, spread her arms, leapt up, and cried, “Pither Borsmutch, / Knock on Wood! / He Went and Did It / ’Cause He Could!” Her arms and legs formed a limber X. “Yaaaay, Piiiitheeeer!”

Visibly, Mr. Valona winced. “Please, a little less enthusiasm.”

Addi curtsied and obeyed. Relieved, Mr. Valona led his charges back toward the main building and a row of Carolina cypresses in tubs. These hid a shelving unit full of rubber trashcans and their shield-like lids. On the way, they passed a metal trough packed with black humus, leaf mold, sprigs of moss, and shredded scrap paper. Several kinds of mushrooms grew in this trough, but not in orderly rows. Mr. Valona pointed out a morel, a destroying angel, a honey mushroom, a turkey tail, a chanterelle, and a king bolete. The chanterelle smelled like ripening apricots. The destroying angel rose inside a plastic box with a chunk of granite atop it. Across the box shone a duct-tape strip on which someone had printed in permanent marker: DO NOT TOUCH—POISONOUS.

“They’re all gross,” Addi said. “Except the turkey tail—it’s sort of cute.”

“They’re all gross,” Addi said. “Except the turkey tail—it’s sort of cute.”

“They’re interesting looking,” Joel-Brock demured, diplomatically.

“If you’re interested in gross garbage,” Addi said. “But if I ever have a daughter, I might name her Chanterelle.”

“Very pretty,” Mr. Valona said.

Joel-Brock said, “Very hoity-toity.” A favorite putdown of Arabella’s.

“Let’s go down,” Mr. Valona said.

Finally, Joel-Brock thought. He and Addi fell into step behind Mr. Valona. He led them through several Carolina cypresses before the only substantive wall in the Garden Center and, pushing their branches aside, squeezed between two saplings. The children followed, and all three stood before a dazzling watery glow, like you see on the sides and floors of a well-lit swimming pool at night.

Stretching down, farther down, and farther down yet, was a moving staircase with coppery steps and rails like huge rolled strips of licorice. It plunged into the abyss below them. The steps kept plunging, the staircase’s reddish sheen often touched with pulses of deep-ocean blue. Alarmingly, Joel-Brock could not see the bottom of the vanishing steps, which glided down-down-down but emerged again from the Garden Center’s floor, so that he decided, well, if steps could recycle, maybe bodies could too—an uplifting sort of notion if also a kind of crazy one.

Beside him, Mr. Valona said, “Who wants to go first?”

“I do!” Addi briefly teetered before grabbing a rail.

To avoid looking like a wuss, Joel-Brock stepped onto the stairs, and Mr. Valona eased on behind them. “Use the rail and balance on your heels,” he advised.

And, as if in a dream, they rode into a ginormous space that Big Box Bonanzas used for storage: a warehouse for its gigazillion products, a horn of plenty for all the loyal customers of Pither M. Borsmutch.

Thirty yards away, there rose an up-bound escalator with see-through sides and flickering blue-and-coppery pulses very like their own. That staircase, with its crowd of riders, moved abreast of theirs, ever ascending. The figures on it were buddypards in pink khaki, either old hires or newcomers assigned to carry items up from the warehouse. But Joel-Brock saw them as imposters—beings with tiny differences from what a real person would view as genuinely human. Hadn’t Miss Melba told him that sprols had both fungal and ghostly traits, just as these rising figures did?

First: Their uniforms looked like outgrowths of their bodies rather than distinct pieces of clothing.

Second: Their pancake hats had gills underneath—gills teeming with tiny spores. The spores sifted out in powdery varicolored spills. One gobbymawler had a halo of red spores behind its head; another, a long plume of lavender motes.

Third: These quasi-humans popped in and out of view like teleporting ghosts, a talent that Joel-Brock checked out as they ascended. A sprol with a white face abruptly vanished, but another, sixty feet below in a plum-colored cap, faded away in a lingering half-minute.

Fourth: Gobbymawler sprols, Miss Melba had said, were all mutes. They could no more talk than a daisy. But she swore they could e-mail, text, tweet, and project their “voices” into animals and human beings.

Fifth: —

But four examples of gobbymawler oddities were enough for now. Joel-Brock had too many sad worries already, especially with his unremitting grief droning like a vacuum cleaner in a distant room.

At the foot of the staircase, a wide enameled floor rose toward them. To the sides of both escalators curved rings of well-padded chairs, places for older buddypards to prop their feet, sip lemonades, and chat before returning surface-side to work. Addi, heedless of her lopsided backpack’s weight, tap-danced down the moving steps.

Mr. Valona called, “Careful, Miss Coe. Careful!”

“Got to go,” Addi called back. “Really, really got to go!”

“Me too,” Joel-Brock said. “This is the longest escalator ever.” Given the length of the trip, he half-expected a group of buddypards to greet them with snacks. Instead, Addi found a restroom under the escalator and waited outside it, hopping from foot to foot, for its current occupant to emerge. Joel-Brock jumped in line behind her, and an old song, “It Must Be Raindrops,” played loudly over a nearby sound system. The person in the restroom finally came out, but the door clicked shut before Addi could catch it and hop inside. When her one attempt to pry open the door failed, she struck it with her fist—whereupon a small mouth-like hole in the door spoke:

“To enter, you must answer a simple history question or slide a dollar bill into the receptacle to your right.”

Addi gawped at the door. “You’d charge me to pee?”

“Only if you fail to answer my question,” the door said—reasonably enough, in Joel-Brock’s opinion.

“Okay, okay. Ask your stupid question.”

“Mind your tone and vocabulary, miss.”

Through tightened lips, Addi seethed.

“Ready? Good. Here goes: In what year did Pither Borsmutch open the first Big Box Bonanzas store in Hawaii?”

“Hawaii? How should I know? How many college professors would know? It’s a ridiculous question.”

“Wrong,” the door said. “Next.”

“Wait. Who at any university could answer that question?”

“Business students at hundreds of fine schools could answer it. So I ask again, young miss: What year?”

“1066! 1492! 1999!”

“I asked for an answer, not three guesses. Next.”

Joel-Brock eased Addi aside. “Please, Mister Door, give me what you promised Addi—‘a simple history question.’ ”

“Okay. Ready? In what year and city did Mr. Borsmutch open our country’s first Big Box Bonanzas store?”

“That’s two questions,” Joel-Brock said.

“What a farce,” Addi grumbled.

“Take your pick,” the door said. “Answer whichever you like.”

Over Joel-Brock’s shoulder, Addi shouted, “Cobb Creek, Georgia!”

“A disqualified person has answered the second half of your question,” the door told Joel-Brock.

“That’s all right, Mister Door. I would have said the same thing.”

“Honestly?”

“Cross my heart.” Joel-Brock crossed his heart. “You asked me a simpler question than you asked Addi, Mister Door.”

Mister Door triggered a mechanism to free its latch, and when the door swung open, Joel-Brock caught it and nodded Addi in. Blinking her thanks, Addi slipped past Joel-Brock into the restroom and closed its door. Joel-Brock sighed. But he could stand the pressure. And, if he couldn’t, somewhere in the lounge he’d find an out-of-the-way redwood planter and water the sapling in it.