3

Home Alone, Sort Of

On a ratty loveseat in the hall of Miss Melba’s cottage on Jarboe Street, Joel-Brock lay thinking about the last time he’d seen any member of his family.

On that afternoon, coming home from Saturday’s ballgame with his friend, Luc Winter, and Luc’s mother, Krista, he had not thought it weird that no one in his family awaited him. His mother, Sophia, a fitness trainer, ran eight miles or more a day getting ready for the marathons that would qualify her to run in next year’s Boston Marathon. His father, Bryden Lollis, worked as a computer troubleshooter, menu maker, and stand-in chef for Lollywild, a chain of sports restaurants that Bryden had started in Cobb Creek twenty years ago.

On that day, though, Bryden had driven Arabella to oboe practice. She played twice a week at a local music school, and because Arabella’s oboe teacher said she had “a clever lip,” she now signed all her email messages FOPOA, which meant Future Oboe Player of America.

“If I hadn’t called myself FOPOA,” Arabella said, “Joel-Brock would never have signed his messages Home Run Hitter of the Future.”

Joel-Brock knew that accusation to be true and that Arabella wanted to shame him by saying so, but he didn’t care. His sister was smart, especially so about words and their meanings. Once, when she was only eight and her teacher asked for an example of a noun and no one in class raised a hand, the teacher looked at her and said, “Arabella, give me an example of a noun.” Immediately, Arabella replied, “Abolitionist?” And this story had become holy Lollis family lore.

Anyway, the house stood empty when Joel-Brock got home. His Cubby League team, the WorkOutWarrior Braves, which Sophia’s business sponsored, had won their game 14 to 2. He had reached base twice on walks and once on an error-assisted “triple.” But he did not undress or shower. Instead, he curled up on their soft, sectional sofa, whose color—gray or lavender—depended on which way you rubbed its upholstery. He clicked on the TV, found a big-league game, muted the sound, and fell asleep watching it. When he awoke, twilight had fallen and a lump of worry freighted his gut. He called Sophia’s cell-phone and got sent straight to her voicemail.

“Mama, I’m home. We won. I’m hungry. That’s it. Bye.”

He called Bryden’s cell, which sent him to his dad’s voicemail. He would have tried Arabella’s phone, but she still didn’t have one. She was twelve. Something else was wrong. The Lollises had three dogs: a wire-haired terrier named Sparky, a King Charles spaniel named Leo, and a jittery old female Chihuahua named Josie. Sophia had adopted Josie from the Cobb Creek humane shelter. Josie had spent most of her life as a breeder in an illegal puppy mill, and her ill treatment and many pregnancies there accounted for her mistrust of human beings, especially men, and also, presumably, her near-constant trembling. Anyway, Joel-Brock now realized that none of their dogs had run out to meet him or curled up on the sofa next to him as he slept, and the absence of the family dogs truly began to unnerve him.

“Sparky! Leo! Josie!”

He opened the door to the deck above the backyard, where, during the day, the dogs played, slept, or did their business, and he called their names again. Again, he got no response. Although deeply worried, he went to the kitchen for something to eat. When he found nothing good, he thought about calling his pal Luc Winter’s mama. He didn’t, but only because he knew his family would soon arrive and he’d appear a total wuss for fearing the worst. But they didn’t arrive, and they kept failing to arrive.

Around 8:40 p.m., Joel-Brock began exploring various rooms—his own, upstairs, and Arabella’s, strewn with clothes, trinkets, and books. Mama had not left a note on his pillow or propped against the fish tank. And in Arabella’s sty of a room, with its bead curtain and tiny lilac-colored door into the unfinished attic, he would need a bulldozer to uncover a school bus. So Joel-Brock returned downstairs. And, under the living room’s cathedral ceiling, he padded past the sectional couch toward his parents’ room, which felt off-limits to him. Why? On late Saturday evenings, Bryden let him cuddle up beside him there. And Mama often called him in to feed Josie, who slept with his parents rather than in cages, as Sparky and Leo did. So, although he had no good reason to avoid this room, tonight, feeling like an intruder, he hesitated before entering.

Then he found his mother’s note—not on the king-size bed or the bureau covered with family photos, but under a magnet on the bathroom mirror’s outer frame. Sophia had written it in red ballpoint on a sheet of graph paper, just as she did the lists she put on the refrigerator detailing everyone’s weekly appointments. The note said . . . well, just what Miss Melba had read silently in Big Box Bonanzas a couple of days ago, and what Joel had read that Saturday and learned by heart: scary stuff about gobbymawlers stealing his family away and about his need to stay inside, eating what he found in the house, praying for a happy ending, and not calling the police.

Restless on Melba Berryhill’s ratty loveseat, Joel-Brock reflected that the BBB kidnappers still had not let his family or the dogs go. And the Cubby League Braves had played two games without him since he’d found Sophia’s note, one during his first days alone and one soon after he’d started bunking on Jarboe Street. Maybe Sparky and Leo had run off, scared, after slipping through a hole under the fence.

He recalled that first fear-racked week. One good thing had happened: When he’d taken Mama’s note back into his parents’ room, Josie stuck her nose out of a gap between two huge pillows against the headboard. This was her hiding place when Sparky and Leo fought. The gobbymawlers had missed Josie because she’d huddled there when they burst in. Now poor Josie shook like a rough-running lawnmower engine. His reunion with her was sweet, for over the past three years, Josie had come to trust Joel-Brock. Sometimes she even slept with him. He hugged her, wishing that she’d open her gray muzzle and tell him about the kidnapping, but instead, trembling, she licked his fingers with her tiny pink snail of a tongue.

Other things that week had not gone well. Some fruit in the fridge had softened, but the cantaloupe wedges were as hard as cucumber rinds. He spit their mealy pulp into the trash and hurled the mushy apples and peaches over the fence into a vacant lot. As for the food in the pantry, Joel-Brock ate as many energy bars as he could stand, but tossed corn chips and stale crackers out for the birds. A tin of tuna, which he’d found under a box of black tea, resisted his struggles to cut its lid off with a can opener. And when he gave up on cereal and canned meats, he burnt the eggs he was scrambling and a horrid stench filled the kitchen.

On day two, Will S Gato, their cat, showed up at the door meowing to be let in. (Maybe he’d smelled the tuna.) Joel-Brock stroked him until the cat bit his wrist and the boy swatted him. Will S Gato flattened his ears, spat, and shot under the sofa.

“You stinker! No wonder the gobbymawlers didn’t take you!”

On day four, Joel-Brock cracked the blinds on a front window and peeked out. A gobbymawler squatted on the porch staring at their door. If she wasn’t a gobbymawler, she was a person wearing the pinkish-brown jumpsuit of a Big Box Bonanzas worker and a soft round cap—like a fat pancake—of the same color. Joel-Brock sidled out of sight. Even though gobbymawlers had stolen his family, he wanted to think of the arrival of this buddypard—as store managers called all their hires—as a courtesy call. He liked visiting the store, and maybe this buddypard had brought him a fresh pizza sample or a booklet of “valuable coupons.”

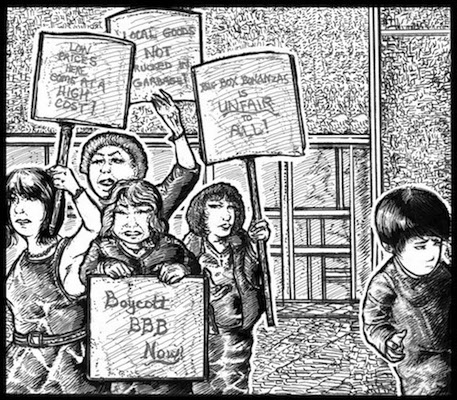

Still, Sophia often said that she could shop there only if she held her nose. Joel-Brock had never seen her holding her nose, but he had heard her curse its lack of quality goods, the fact that stuff she liked too often vanished from its shelves, never to return, and its “disgraceful” treatment of its employees: greeters, baggers, stockers, checkers, gardeners, shoplifter spotters, et cetera. And, then, just this past winter, it had all gotten serious for her, and she began a heartfelt battle against the store. She asked friends to pitch in, and she, four other women, and two of their husbands paraded in a parking-lot picket line. Their signs screamed BIG BOX BONANZAS IS UNFAIR TO ALL, and LOW PRICES HERE COME AT A HIGH COST, and LOCAL GOODS—NOT TRUCKED-IN GARBAGE, and so on. Reporters covered the protest. Segments appeared on the TV news and write-ups in the papers. Several kids at school, who liked Big Box Bonanzas as much as Joel-Brock did, called his mama “eco-freak” and even some uglier names that hurt his feelings worse. A few kids sided with him, but Joel-Brock thought the whole thing a huge embarrassment. Why had Sophia gotten so bent out of shape?

Knock-knock, knock-knock-knock, knock-knock! Whoever had just crept onto the porch knocked, again and again, with the brass knocker. “Boy-o, open up!” the strange female yelled. “I’ve got news for you!”

This buddypard seemed to be a teenager, but her shouts terrified him. Did she want him to open up so that the creeps who’d snatched his family could grab him too? Go away, Joel-Brock prayed, but the buddypard kept knocking and pacing about. He peeked through the blinds again. His tormentor was a teenage girl—with coppery hair, emerald-green eyes, and a sharp but fetching face, even when she muttered. Finally she left and never—so far as Joel-Brock knew—came back. So at the end of that week he determined to get a job. Then he’d buy pizza and broccoli, which, although otherwise a normal kid, he really liked.

He didn’t call the police or DFACS or anyone else on his mama’s list, but he did wonder why no friends of his parents had phoned or come by. Hadn’t they missed him at the last two games? What in the world had happened? Well, using his father’s laptop one day, he discovered that Sophia had posted a FacePlace notice saying that the Lollises had gone on vacation: “Three big and hungry watchdogs are guarding our house.” She must have posted this message—this lie—hoping to keep Joel-Brock safe, and she must have done so just before the BBB gobbymawlers whisked her and Bryden and Arabella out of their house.

On his second Monday alone, he put out food bowls for Josie and Will S Gato and, wearing his dirty baseball duds, left for Big Box Bonanzas. Dusk had gelled into muggy summer dark and he hiked along the road sweating. Vans, roadsters, and trucks whooshing by all seemed as tall as jacked-up Monster Mash jalopies. The driver of an 18-wheeler, seeing Joel-Brock, sounded his air horn: BLAAAT! Joel-Brock wobbled and fell over. On his hands and knees, he thought: You. Big. Butthead. Meanie.

He got up and resumed his march. He liked Big Box Bonanzas. Once, his mama had gone there for photography supplies, vitamins, scrapbooking materials, candles, and Halloween candies. In emergencies, his daddy still bought fresh meats and veggies for the Lollywild restaurants there. And Arabella still visited BBB for shampoo, paperback young-adult novels, and snap-on beads and bracelet charms.

And there, almost before Joel-Brock knew it, shone Cobb Creek’s Big Box Bonanzas, a beacon in the dark.