1

Home Run Hitter of the Future

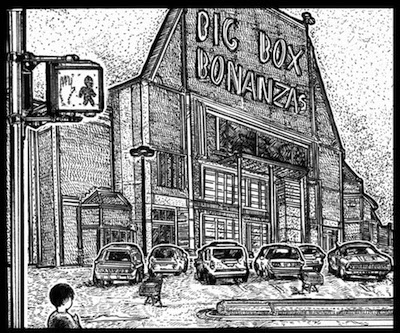

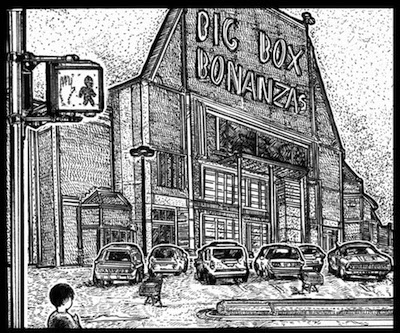

Joel-Brock Lollis secretly thought of himself as the Home Run Hitter of the Future, but on this hot summer evening he also thought of himself as the loneliest nine-year-old in the world. He had hiked nearly three miles along a blacktop two-lane from his house on Crabapple Circle toward Big Box Bonanzas, his favorite store in Cobb Creek, Georgia. Even wearing his Cubby League BRAVES uniform didn’t turn his mind to baseball. Too much other stuff fretted him.

First, he’d seen no member of his family for over a week. Second, his stomach ached. Third, by leaving the Lollis house, he had disobeyed his mother. Fourth, hiking the road’s weed-grown shoulder in the gloom of a fading sunset really scared him. Fifth, even though he’d tried to wash his uniform, it bore lots of stains and stank of boy sweat. And, sixth, he had no idea if his journey to Big Box Bonanzas would chase away any of these worries.

Not far from his destination, Joel-Brock stood like a wide-eyed lemur in a jungle of hungry leopards. He was at a crossing waiting for the light to change. And when the WALK sign lit up and he stepped into the street, headlights glared and dozens of engines snarled all around him.

“I wish I was a giant and weighed ten tons!” he shouted at the traffic.

Once across, Joel-Brock stopped on a curb beside the big store’s parking lot. Its tarry surface rolled off into the twilight toward windows that blazed like bonfires. Long ago, there had been a strip mall here, but the owner of Big Box Bonanzas had bought it and torn down all its little stores to build this humongous one. Now cars popped into and out of the lot’s lined spaces like giant metal honey bees on a melting hive.

Joel-Brock skipped between the cars and into the entryway of the boxy store. He nodded at khaki-clad greeters, passed checkout lanes, and headed for Electronics, where he found Melba Berryhill, his favorite employee in the store.

“I would like a job,” he told her.

Miss Melba, a chocolate-skinned woman with hair like bristly cotton, looked at him with surprise. She could not recall Joel-Brock’s name, but his cocker-spaniel eyes and skinny arms made her want to hug him and tote him home. But her shift did not end until midnight, and kidnapping the boy at this moment would not please her boss.

“Now, why would a kid your age need a job?”

“My family’s disappeared,” Joel-Brock said. “And there’s not a lot in our house left to eat.”

“Then you should call the police or Family and Children Services.”

Joel-Brock’s eyes pled with Miss Melba.

“What’s your name, young man?”

“Joel-Brock Lollis.” He did not say Home Run Hitter of the Future because she would scoff or scold him for bragging. So far in his baseball career, he had hit only one “home run.” And he’d made it around all the bases only because of a flurry of throwing errors by the boys on the other team.

“Well, Joel-Brock Lollis, you still should tell the police or DFACS.”

“I can’t,” he said, and he yanked a note from the back pocket of his baseball pants and handed it to Miss Melba. She read it to herself. These were the words that his mama had scrawled on that grimy scrap:

Darling Joel-Brock,

If you contact the police or the Department of Family and Children Services, your teachers at school, any of your friends’ parents, or almost anyone at all, the gobbymawlers who have spirited your daddy, Arabella, and me away will never let us return to you.

So please stay inside the house with the doors locked and wait. Eat all the fruit and anything else you find in sealed packages in the pantry. And every time you give thanks for your food, pray for our early release by the contemptible stooges of the worst man in Cobb Creek, and maybe they will let us come home before your next game.

Love, Mama

Miss Melba peered at the boy with a sharper look of bewilderment and distress. “I still think—”

“No,” Joel-Brock said. “Not by the hair of my chinny-chin-chin.”

“Joel-Brock Lollis, you’ve got no hair on your chinny-chin-chin.”

“Okay, then—‘not by my skinny-skin-skin.’ I won’t do anything that’ll keep my family from coming home.”

“But you ignored your mama’s plea to stay inside with the doors locked.”

“She’ll know why I did that. Things are different now: I’m hungry.”

“Then you do need a job, but a job here will turn you into a gobbymawler. Is that what you want?”

“When Mama says gobbymawler, she means stinker or pain in the neck, not just somebody who works here. I don’t know why.”

“Your mama doesn’t like this place. Her name shows up a lot in our Complaints records.”

“Please, Miss Melba—you’ll see how hard I work.”

“Okay. But when my shift ends, I’m taking you home. I’ll give you a pork chop, turnip greens, and pot liquor.”

“I don’t drink liquor.”

“With pot liquor, babycakes, you can use a spoon.”

“I mean I don’t touch it.”

“No,” Miss Melba said, “I don’t reckon you do.”

*

A clock radio in Electronics ticked over to show the digital time: 9:24 p.m. Only a few people prowled the aisles. Miss Melba said that little business got done on slow weekday nights, so she had time to spray some air freshener all around his head.

“I feel sticky, Miss Melba.”

“Maybe you oughta feel a bit like you smell.” She added, “Just kidding, mostly.”

“But why do you have to do that?”

“If you want a job, babycakes, you can’t smell like a sweaty-sock closet.”

At that moment, Miss Melba’s night-shift boss, Augustus Hudspeth, appeared. He asked who the short-stuff in the baseball uniform was and why the kid kept switching all the TVs, computers, and DVD players on and off.

“He’s Joel-Brock Lollis, my nephew,” Miss Melba said. “He wants a job.”

“Your nephew? Melba, this hyperactive little fellow is white.”

“No sir, he’s biracial. That’s all.”

Mr. Augustus Hudspeth loomed tall. He had love handles that made his shirt look rumpled and a belly that made his tie look too short for his shirt. “Tell him we can’t hire children, Melba. And nobody’s supposed to bring a kid to work.”

“I didn’t, sir. My sister dumped him off. I just figured I’d give him a chance to learn something by watching me do my job.”

“You’re not working, Melba—you’re babysitting.”

Joel-Brock turned away from the monster FōFumm TV now showing the Atlanta Braves playing the Colorado Rockies. “Nobody babysits me,” he told Mr. Hudspeth. “I’m ten—almost ten.”

“Come on, sir,” Miss Melba said. “Give us a break. He’s a strack little soldier.”

“‘Strack’?” Augustus Hudspeth said.

“That’s army talk. It means ‘sharp as a tack.’ I think.”

Joel-Brock blushed at his grubby uniform.

“Okay,” Mr. Hudspeth said, sniffing. “But do me a favor: Wash that watermelon-rind air-freshener stink off the boy. Somebody’s likely to cut him into strips and slop the pigs with him.”

“Augustus,” Melba said. And then: “Mr. Hudspeth.”

Yipes, Joel-Brock thought.

“And keep him out of our customers’ sight. This is just for tonight.”

“Yes sir. Thank you, sir.”

*

But “just for tonight” turned into every night . . . except Thursday, Miss Melba’s day off. She told Augustus that her sister had left her son to join a convent, and that she, Melba, was now the boy’s “temporary keeper.” Actually, she had no sister.

“I’d have your sister arrested,” Augustus said, but he found Joel-Brock jobs as a go-fer and an assistant shelf-stocker. He could do these jobs without much harming Miss Melba’s own performance. Once finished helping Kyle Robinson restock Toys and Shel Burgess carry woks and vanilla candles to the Home section, Joel-Brock duck-walked, really low, to Electronics and clicked on the FōFumm TV to watch that evening’s Braves game. Augustus, also a fan, stopped in to check out the action. But tonight the Braves and their opponents, the San Diego Padres, looked . . .

“Different,” Augustus said. “And I mean different.”

“They’re wearing shorts,” Joel-Brock said.

“And skintight sleeveless jerseys,” Augustus said.

“And hats with bells and floppy brims,” Joel-Brock said. “And two-tone shoes with blinking blue lights.”

Augustus groaned and said, “What kind of silly promotion has the Braves’ front office dreamed up now?”

And both he and Joel-Brock realized that the Braves in this lineup—Sealy, Coffin, Safransky, Pfingston—were not the players they usually cheered for. They’d never even heard of these dudes.

“They must’ve called up a bunch of minor leaguers,” Augustus said. “But why? It makes no sense at this point in the season.”

“I have no idea,” Joel-Brock said. His parents and his sister Arabella used this expression a lot. But none of the Padres had familiar names on their jerseys, either. (The name on their pint-sized shortstop’s shirt was Chou Shu-Hu.) However, Joel-Brock did not point out these facts to Augustus because he feared that doing so would only irritate his supervisor more. “Maybe it’s okay,” he finally said. “We’ve got two runners on and just one out.”

Then a Braves outfielder named Pfingston—Pfingston?—struck out. Augustus shook his fist. Then a slender player strode into the batter’s box and took up a confident stance. The announcer identified him as J.-B. Lollis, the centerfielder batting .406 with 21 home runs, 64 runs batted in, and a .788 on-base percentage.

“Lollis,” Augustus Hudspeth said. “What a set of statistics! You related to this guy, Joel-Brock?”

“I have no idea. I’ve never heard of him.” And he hadn’t, but the name, so much like his own—almost identical—sent an eely shiver up his back.

Miss Melba came up behind Augustus and her “nephew” to check out the game. “What stylish uniforms,” she said.

“Maybe on that kid,” Augustus said. “But some of those guys look like they’re wearing silk boxers. And those shoes belong in a circus.” J.-B. Lollis took a called strike. “What’re you waiting for?” Augustus yelled. “Hit the ball!”

“He’s feeling the pitcher out,” Joel-Brock said.

Next, J.-B. Lollis watched a sinker drop low and away for a ball. Augustus rolled his eyes again. “Guess he’s still feeling the pitcher out,” Miss Melba said.

J.-B. Lollis walloped the next pitch into the second tier of seats in left-center. The stadium’s sound system played “Eye of the Tiger,” and the Braves led the Padres 3 to 0. Joel-Brock and Miss Melba high-fived. Augustus did a locomotive shuffle all around the inside of the Electronics section. “Yes-yes, yes-yes, yes-yes.” he choo-chooed.

Joel-Brock’s namesake circled the bases and crossed home plate into a mob of pogo-sticking teammates. The fans, too, were jitterbugging about and pumping their fists. J-B Lollis trotted free of his teammates and tipped his floppy hat.

“He’s like your older brother,” Miss Melba whispered to Joel-Brock. “You two favor like bream in a lake, a big one and its little twin.”

*

On the next afternoon, Augustus asked Joel-Brock if he had looked up the result of last night’s game in the Atlanta Constitution.

On the next afternoon, Augustus asked Joel-Brock if he had looked up the result of last night’s game in the Atlanta Constitution.

“No. No, I didn’t.”

Augustus said, “Well, I did—online—and the Braves lost 7 to 2.”

“Uh-uh,” Joel-Brock said. “They won on—”

“No, they didn’t. And I couldn’t find one Brave in the paper named Pfingston, Coffin, or Sassafras.”

“Safransky,” Joel said.

“I only found our regulars guys, guys who always play: Freeman, Heyward, and the rest. So I have to ask: Who are these Braves with the funny names that we watched on TV last night?”

“I have no idea,” Joel-Brock said.

Miss Melba chimed in: “It’s Braves from another reality—your big brother from a sideways universe that we got on TV yesterday by sheer freakiness.”

“I don’t have a big brother.”

“Not here, but in that other reality—it’s the only explanation.”

Joel-Brock ducked out of the service area and sat down in a cave of TV boxes in front of the appliances. He was breathing like a dog that has trotted miles to find shelter from a thunder storm. Miss Melba got down on all fours, dog-walked over to the boxes, and peered inside.

“What’s wrong, babycakes?”

Joel-Brock whispered, “Don’t call me babycakes.”

“What’s wrong, Joel-Brock Lollis?”

“I don’t have a big brother.”

“Not in this reality you don’t.”

“Not in any. And in this one, I don’t even have a family.” He started his dogtrot-breathing again—but softly, trying hard to stifle it completely.

“Oh, honey.” Miss Melba reached into the cave of boxes, but by now he’d backed farther in. “Joel-Brock?” No answer. “Joel-Brock?” No answer. “JOEL-BROCK!”

“what?” he said in his smallest voice.

“We’ll find them. Don’t fret, now: We’ll find them.”

Joel-Brock clasped his knees and, in a rush of bitterness, thought, Yeah, right.

Then Augustus Hudspeth said, “At nine-thirty I’m going to turn on that big flat-screen so we can catch up on our bubble-universe Braves. You’d like that, wouldn’t you? Boy oh boy, so would I!”