Douai, Flanders

May 10, 1636

Diogo screamed in the darkness. The dream had come again.

"Diogo, are you alright?" Flint scraped and a candle flared, casting light and shadow in the dormitory room.

"I, I, I had the dream again, Symao!" Diogo shuddered, arms wrapped around his chest, sitting up in his narrow bed.

The door slammed open, and Father Matteus Arrostegui was silhouetted in the torchlight from the corridor. "What is the matter?"

"Diogo has had another nightmare, Father," Symao said wiping the sweat from the other African's brow. "His escape from the Imbangala."

"Are you alright?" The priest asked Diogo. Father Matteus came into the small room about as far as he could. There wasn't much room for two seminarians, their beds, and the priest. Diogo nodded jerkily.

"Sim, Father, I – I think I am fine."

Symao stood next to Diogo's bed, with his hand on Diogo's shoulder.

"He should be better tonight," Symao said. "The nightmares don't come back after Diogo wakes."

Symao moved back to his own bed; his own dark skin outlined against the whitewashed wall of the sleeping chamber. "We will be fine, Father."

Father Matteus rubbed his forehead, trying to think clearly despite the hour. "Come to see me in the morning directly after Matins, both of you," he said. "We will see how best we can help you." He made the Sign of the Cross over them.

***

In the morning, Diogo and Symao washed up, put their black cassocks on and cinched them at the waist with belts made from their rosaries, put on their sandals, and went to Matins.

After Matins, not even looking for breakfast, they took a collective deep breath and went to find Father Matteus.

"It will be fine, Diogo," Symao said quietly as they walked down the hall in the rectory. Symao looked on the younger man as a sort of little brother. Diogo and Symao were the only two Africans studying at the Jesuit Seminary in Douai, and Symao, having been born and grown up in the city of Luanda, capital of Portuguese Angola, felt himself to be more worldly than the younger Diogo, who had come from a small village to the east of Luanda. Because they were the only Africans, the proctors had decided they should room together. Their very dark skin stood out among the blonde and red-headed Netherlanders.

At the end of the hall, they found Father Matteus' office. They knocked softly on his door.

"Come in, young scholars," Father Matteus said in Portuguese. The prefect of seminarians of the Jesuit seminary at Douai smiled tiredly at them and waved them to a pair of hard wooden chairs. Diogo and Symao looked at each other and, hiking up their cassocks a little, sat down.

Father Matteus sat back from his desk and put his arms inside the sleeves of his cassock. He had their files before him on the desk, but he looked straight at the two young men.

"You two are my only seminarians from Africa," he said. "I know little about the life of the Church and of the Order there. Tell me about yourselves."

Symao spoke first. "I was born in Luanda, Father. Luanda is the capital of Angola. It is a large city, and the Church of Jesus is one of the largest buildings in the Southern Hemisphere. My father was a merchant, and after he died, I found myself called to a vocation, and I entered the Society of Jesus there. I came to Portugal and thence to Douai to further my education and teach." He shifted nervously on his chair and crossed his legs inside his cassock. His arms mirrored Father Matteus' inside his cassock sleeves.

Matteus nodded. "You are in minor orders, yes?"

"Yes," Symao said. "I am a deacon. If all goes well, next year I shall be ready to be ordained a priest." His eyes flashed and his smile was full of white teeth. "I pray daily for that occurrence, Father."

Father Matteus looked at Diogo expectantly. "I too am a deacon," Diogo said. "I too hope for ordination next year . . ."

Matteus looked at Diogo and then at Symao. "You may go, my son. I wish to speak with Diogo privately."

Symao exchanged looks with Diogo. Then he rose from his chair, and silently glided out the room, closing the door quietly behind him.

Father Matteus took a deep breath and let it out slowly. "My son, I would like to act as your confessor while you are here, and while we perform the Spiritual Exercises. Are you willing?"

"Yes, of course, Father," Diogo said, confused.

"I see I must explain," Matteus said. "I need to determine the state of your soul, my son. I need to know everything about your nightmares, so I can tell if you are demon-ridden. The Jesuits who live in Grantville and Magdeburg in the Germanies say that there is a condition called post-traumatic stress disorder. It is my task to determine if you are suffering from this PTSD or something deeper and more evil. Do you understand?"

Diogo nodded mutely. Matteus said, "You must agree out loud, my son."

"Yes, Father, I agree, and I understand."

"Good. I bless you in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Now tell me about your nightmare. Is it always the same?"

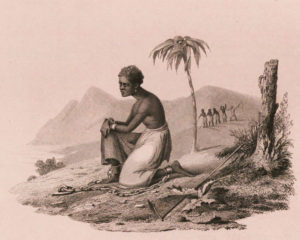

"Yes, Father. It always starts in my village. My father was the chieftain of a small farming village in the eastern part of Angola. It was a bright, beautiful day, and I was feeding the chickens. Suddenly, the village erupted in noise as people we had never seen ran into the village square and started killing us, mostly the women and children. My father went to try to stop them, and one of them had a sword, and he cut my father down. The killer was a huge man, very black, and his face was all twisted up in a grimace.

"They rounded us all up and made us stand there while they killed nearly all the children and the pregnant women. I knew then who they were, Imbangala. They grabbed me, and I think they were going to kill me too when my father's killer grabbed me and made me look into his eyes. 'How old are you?' He asked me. I said I was seventeen. 'You are old enough to join the Imbangala,' he said. 'Tonight there will be an initiation ceremony.' He motioned to several of his men, and they took me and tied me to a tree.

"One of them, a wiry old man, stayed with me and told me that I was to break from my past in a ritual that called for me to kill and eat a baby from the village. When he told me that, I threw up. He thought it funny and laughed at me."

"Who are these Imbangala then?" The old priest was visibly shaken.

"They are warrior bands who have suddenly invaded our lands from the east, Father. I don't know where they came from. They are not a tribe or a kin group—they insist that you have to be initiated in order to become an Imbangala. Children born inside an Imbangala village are killed. That was what was going to be my initiation ritual. The old man told me a lot of things about being an Imbangala. I would not be a real one until I killed my first victim in combat. He said that they often fought as soldiers for the Portuguese. They were looking for a place to settle down, the old man said, but they never seemed to actually do it.

"And all the while he was talking to me, the rest of the Imbangala were torturing and killing my relatives and friends and neighbors, and, um, performing the ritual."

"And did you fulfill the ritual?" Matteus said, softly. "Did you kill and eat the child?"

"No, Father, I did not, but I saw people who did. I had been chafing the rope that held me to the tree all day and it finally gave way. When I saw that all eyes were on the horror happening to my little cousin, I ran. I ran all night and all the next day. I kept throwing up, from just thinking about it.

"Then, I ran into a troop of Portuguese soldiers who were on patrol. They captured me. They beat me and put me in shackles. They were marching from village to village, picking up slaves to sell at the coast. I remember the beatings. I think that I nearly starved. We got some water in the morning, and a crust of bread and some water in the evening. At night we were shackled to each other so we could not move. We stank so badly. We heard the lions in the brush, and we prayed very hard that they didn't want to eat us.

"Finally, they took us all to Luanda, to sell us into enslavement. They put an iron collar on me, as well as keeping my shackles on, and dragged me along to the slave pens by the river. When I was there, I was sold to the Jesuit fathers. It amazed me that the Jesuits would own slaves. But they did, and do. They support the slave trade between Angola and Brazil. They bought me, because they wanted somebody to work in their garden and grow vegetables for them. It surprised them that I could read and write Portuguese. They set me free after hearing my story, but I decided to stay with them. I didn't even try to find my family because I was sure that the Imbangala had killed them all, or worse. I didn't want to know.

"It was then that I decided that I wanted to join the order. I wanted to learn Latin so I could talk to the other Jesuits about slavery, and how wrong it is. The Collegium in Luanda taught me Latin, and I found a vocation there as well."

"Ah," Father Matteus said. "Tell me more about these Imbangala."

Diogo ran his fingers through his tightly kinked hair. He wore it clipped close to his scalp so it wouldn't harbor vermin.

"We don't know where they came from," he said. "We think they came from the interior. They are very fierce. They are trained to show no fear. And they love to drink palm wine until they are stinking and falling down drunk. They do not allow women to give birth in their camps. They kidnap youths like I was to increase their numbers.

"They have worked for, and then betrayed, the Portuguese as well as the great Queen Njinga Mbande. She is half an Imbangala herself. It is said she somehow made herself a man and went through the ritual of butchering a baby in the bowl of a huge stone mortar. I do not, myself, know if that is true or not."

"The Jesuits in Luanda owned slaves?" Father Matteus asked softly, visibly catching up to Diogo's story.

"They did, and as far as I know, they do still. They say that it is a natural thing to own black slaves, and if good Christians do it and help their slaves to understand and serve the Son of God, it is a godly thing to do, as well. But Father, that can't be true! It just can't be!" Diogo burst into tears and was shaking. "Being an enslaved person is the most hideous fate there is," he said. "Imagine not being able to make a single decision for yourself, Father. You are a piece of property, like this bed, or your shoes. I cannot imagine that the good Jesus would want us to have slaves. It is even worse than being tortured by the Imbangala. If they torture you and you die, it is over quickly. If you are a slave, you are a slave forever."

Diogo wrapped his arms around himself and was visibly shaking. Father Matteus stood up and put his hands on Diogo's shoulders. The young man relaxed into the embrace and began to weep.

Father Matteus bowed his head and thought. Finally, he said, "I give you this penance—that you pray God for the ability to cope and recover from these events, Diogo, and I absolve you of your sins in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit." He made the sign of the cross over Diogo's head. "Go find your studies, my son."

***

Besançon, Burgundy

June 15, 1636

Father Frederich Spee von Langenfeld, sometimes known as von Spee, a priest of the Jesuit order, walked swiftly down the corridor with his cassock swishing. The whitewashed stone of the corridor leaked in spots and made green moldy patches toward the bottom of the wall. Spee could smell the mold as well as the sharp, wet smell of soaked dog. He looked down to where his new dog was pacing him down the corridor. The dog was large and rangy, with hair so dark, it looked blue. The dog had tan points on his face, and bright yellow eyes.

"Honestly, Midas, how are you supposed to be my bodyguard if you spend all your time chasing the ducks in the moat?" The dog grinned. "You are full of, what does Cardinal Mazzare say, monkeyshines. I know you are named for King Midas, but you might as well be King Monkey." The dog just grinned.

At the end of the corridor was a large wooden door, with a guard in front of it. Spee nodded at the guard. "How are you this morning, my son?"

"Just fine, Father. I believe some of them are waiting for you." The guard turned and opened the door. Spee and Midas walked in. The guard closed the door behind them.

The room was long and a bit narrow. Its ceiling was tall and had clerestory windows on one side, and a fireplace on the other. In the middle was a huge, canopied bed, with a table and some chairs near it. The walls had old, threadbare tapestries hung on them for insulation.

"In God's Name, that dog stinks," Sharon Nichols said from her chair by the huge four-poster bed. "Father Fred, what has he been doing this time?"

Sharon had known von Spee since he arrived in Grantville working to save the life of a young woman falsely accused of witchcraft. So he had become Father Fred.

A dry laugh came from the old man in the bed. Muzio Vitelleschi, the Superior General of the Society of Jesus, spoke softly to von Spee. "Yes, my son. While we wait for the others, we can talk about the dog."

Vitelleschi turned his head toward Nichols. "I know that you up-timers do it all the time, but I would prefer that you not blaspheme and take the name of the Lord in vain."

Sharon Nichols bowed her head contritely. Even though her skin was very dark you could see the blush travel up her shoulders and neck to her face. She put her hands to her face, as if she was suddenly hot.

"And so, Father Fred?" she said.

Spee motioned Midas to go lie down by the fire, away from the bed. "I am sorry, Ambassadora and General, he has been chasing the ducks in the moat again."

Sharon looked over her shoulder at the dog. "Where did you get him, Father Fred?"

"He came from two friends of mine. When it was decided that I would come to Besançon secretly to plan the great meeting, I went in disguise as a musician, and along the way I met two young men from Weimar who call themselves Die Blauen Brudern."

"Die Blauen . . ." Sharon's brow wrinkled. "Oh, the Blues Brothers!" She clapped her hands and laughed. "Was one of them tall and the other short and fat?"

"Oh, yes," Spee said. "How did you know?"

"There was a movie up-time," Sharon said.

"They wore up-time jackets, what they said were 'porkpie' hats, and insisted on being called 'Jake' and 'Elwood.' They were really Max Weber and Heinrich Wollner, from Weimar, though. They had become enamored of the up-timers' 'blues' music. I travelled with them as a disguise and because I too love the blues, they let me play my gitarra in the band.

"But getting to the dog. He was tagging along with them. They told me that he was one of the new breed of hunting dog that Duke Albrecht has been working on—a Weimaraner—but he was the wrong colors, so they were able to take him with them. As we travelled, Midas spent more and more time with me, and when I left Die Blauen Brudern to enter Besançon, he went with me. Jake told me that Weimaraners choose their person, and Midas must have chosen me. He hates to have me out of his sight, except of course when he is chasing the ducks. He hated being locked in my room during the meetings."

Midas raised his head from where he'd curled up by the fire and gave a low woof. He looked at the door and woofed again.

The door crashed open, and in strode Ruy Sanchez de Cazador y Ortiz, the pope's bodyguard, and the ambassadora's husband. Directly behind him came a short parade, led by a man in red vestments over a white cassock and wearing a red skullcap. Then came another man, in a red cassock, and a rather nondescript man brought up the rear.

Sharon stood, and bowed. "Your Holiness. Greetings. And Larry . . .I mean Your Eminence Cardinal Mazzare, and Estuban Miro. Welcome."

The old man in the bed gave a grunt. "Yes, welcome. It is good to see you, Holiness!"

The man in the red cap nodded. "It takes some getting used to," said the former Cardinal Bedmar, now Pope Fabian II. "And it is a good thing that the late Pope Urban and I were much of a size, because we couldn't go looking for a new papal tailor until the news got out. Now, of course, since the conclave, everyone here knows, and the word is getting out daily."

The pope headed for the table and sat at the head of it. Everyone else sat around it, except Miro, who stood between the table and the bed.

"Please, Don Estuban, sit down," the pope commanded. "We are met in a spirit of ecumenism," the pope said. Miro sat.

Cardinal Mazzare spoke first. "Holiness, we must get you to the Netherlands quickly, before someone takes a run at you."

"Yes, I believe the Netherlands is the place to take our stand," the pope said. Midas came over and put his head on the pope's leg and was rewarded with a head scratch and an ear rub. He then walked over to where Father von Spee was sitting and curled up at his feet. "But where?"

"You don't think you should go to Amsterdam?" Mazzare asked. "or Brussels?"

"Not if he wants to appear to be an independent pontiff," Ruy Sanchez replied. "We need to look for a place that has an appropriate palace we can use and is far away from Don Fernando's court."

"Lille," said von Spee. "It is a long day's ride to the court. It is a city with a large episcopal palace and is Catholic."

"Isn't Lille part of France?" Mazzare looked puzzled. "It was up-time."

"No, not yet. It is in Flanders—the Netherlands. It would have been taken by France in about fifty years," Miro said. "Now, probably not so much."

"Good," Sharon said. "Who will go with him, and how will we get him there?"

"Of course, my dear wife, love of my life, I must go with him as the commander of the new Papal Guard." If it were possible to stick out his chest proudly and duck at the same time, Ruy Sanchez had learned how to do it.

Sharon glowered at him but didn't say anything. It was obvious that he was right.

"I can't be away from Magdeburg much longer," Mazzare pointed out. "I need to leave very soon."

"Ahem." Vitelleschi coughed, attracting everyone's attention. "I must, of course remain here, as should the ambassadora. But Friedrich can go as the representative of the Jesuit order to the Papal Court. In fact, Friedrich, you should begin thinking how to disseminate the circular of Pope Urban. It must be disseminated far and wide, and you, Friedrich, are the best writer among us. The circular said some important things about ecumenism, and even slavery. You can do that in Lille as well as anywhere."

By now, everyone was looking at Estuban Miro. He was the one with the dirigible.

"If we leave soon, I can take His Holiness and his party to Lille, and then return to Magdeburg with Cardinal Mazzare."

"That is good, Don Estuban," said Sanchez, smiling broadly. "Now I don't have to figure out how to hijack and fly a balloon."

Midas sat up and barked loudly. "You agree, do you?" Von Spee said, rubbing the big dog's shoulders.

Sharon said, "Okay, then, when do you want to leave?"

Miro said, "Yesterday, frankly. But if we leave tomorrow it will be fine."

She turned to Pope Fabian. "Is that too soon?"

"My daughter, before my vocation found me, I was a soldier. You can assume that there is still enough of General Bedmar in me to be able to decamp first thing in the morning."

***

Besançon, Burgundy

June 16-17, 1636

The dirigible was small and, with the entire party in it, was crowded. It left the ground like a pregnant duck but made it into the air and away from Besançon. Miro steered the craft due north, toward Strasbourg. He landed in Metz for fuel and meals for the ecclesiastical party, and again in Strasbourg. The pope was in mufti, having packed away all the papal regalia so that he would not be an easy target. Ruy had dressed in nondescript clothing. Mazzare was in a simple black cassock, as was von Spee. Midas was in his normal black and tan fur. He seemed to be enjoying the ride. He kept sticking his nose out into the wind passing the gondola.

Luckily, word did not reach the French about who was passing overhead until the pontiff reached Lille. While they were in the air, Sharon had sent coded radio messages to the USE embassy in Amsterdam, and couriers had gone forth to the episcopal palace in Lille. When the pope and his party arrived in Lille, there was an escort ready to meet them and get them settled into what was to become, at least temporarily, the new Vatican. The remaining members of the new Papal Guard that didn't make the airship rode hell-for-leather from Besançon, arriving in Lille two or three days later. Luckily, it was June, and the roads were clear and dry.

***

Lille, The Netherlands

June 25, 1636

Friedrich von Spee sat in his small bedroom, almost a monk's cell, in the Episcopal palace in Lille, writing like a madman. Midas, as always, lay at his feet.

Pope Urban had not written out his last homily. So, von Spee was depending on his memory, fragmentary notes he'd taken, and the notes other people had given him.

"Our Holy Father, Urban," von Spee wrote, "now so sadly martyred, had studied the many documents from the up-time Church. He had been, as we all knew, a very worldly pope, much consumed with the trappings of power and money and rule. But he was struck by a question that Cardinal-Protector Mazzare, a man from the future Church, kept asking. 'When did God ever command us to kill for him?'

"In his last homily at the Council of Besançon, Urban said, 'Our Father in Heaven knows that I am anything but Christlike, but at this late hour, I have finally heard His Son's words. And among them were these: 'If a man has a hundred sheep, and one of them has gone astray, does he not leave the ninety-nine on the mountains and go in search of the one that went astray? And if he finds it, truly, I say to you, he rejoices over it more than over the ninety-nine that never went astray.'

Spee wrote, "The Pope went on, 'Are we to slay the lost sheep because they have become lost? Or are we to accept Christ's teaching: that it is greater to love the wayward of the flock, and to preserve them? And their children, in all their multitudes. This, this, is why we are gathered here in the name of ecumenicism: to stop the slaughter of the sheep. To call them back, that they might come as close as they can.' "

Spee continued to write the testament of Urban VIII, believing that someday these words would be used to crown this formerly worldly priest with sainthood. This would accompany the papal circular that Cardinal Mazzare was sending out over the signatures of both Pope Urban and his successor, Pope Fabian II, the former Cardinal Bedmar.

***

Lille, The Netherlands

July 1, 1636

Friedrich von Spee, his Weimaraner dog at his heels, went looking for Ruy Sanchez. He found him in an office, with a desk covered in paperwork.

"I didn't expect to find you here, buried in paper," von Spee said, coming in the door.

Sanchez groaned and threw a stack of papers down. He reached down and tousled Midas' floppy ears. Midas groaned in ecstasy.

When Ruy was sure Midas was petted enough, he looked up and said, "What can I do for you, Father Fred, that can keep me from this terrible drudgery for at least a few moments?"

"I need to know where the nearest radio is," Spee replied.

"Why, right here." Ruy pointed to the table in the corner with an up-time radio set on it. "What do you need to send, and to whom?"

"No," von Spee said, "I meant a—what do they call it—a broadcast radio station, like the Voice of Luther."

"Ah, I see. The nearest is in Amsterdam."

"I would prefer not to use that one."

"Well, the College at Douai has been building a 'Voice of St. Ignatius' for some time. It must be finished by now. And that is only thirty miles south of here. What do you want to broadcast?"

"I have finished writing a Testament of Pope Urban, and I want to broadcast it."

"When do you want to leave? I will send some men with you," Ruy said.

"How about tomorrow?"

***

Douai, Flanders

July 3, 1636

Von Spee sat on one of the hard wooden chairs in the small office of Father Matteus Arrostegui at the Jesuit College of Douai. "I have been commanded by the Father General, Muzio Vittelleschi, to disseminate the Testament of Pope Urban VIII and the papal circular that he wrote just before his martyrdom. I want to use your radio to broadcast it."

Father Matteus rubbed his forehead and nodded. "We have received letters from Father General. We are looking forward to hearing you. We understand that this is from the up-timers."

"No, not really. Although Cardinal Mazzare, the up-timer who is cardinal-protector of the USE provided some of the material, this is the work of several scholars, as well as Pope Urban himself. As you will hear, Pope Urban went through a significant change in his attitude and his faith at the end of his life. This is the result of that change."

Father Matteus said, "We are in the middle of the Spiritual Exercises with the seminarians. Would you like to teach a sermon to them, as well?"

Von Spee nodded. "Yes, of course. They will be the ones to carry forward this re-creation of God's Holy Church long after we are gone."

"Tomorrow, then? We will broadcast your sermon as you give it."

Von Spee smiled. "That will be an auspicious date. July 4 is a date that is near sacred to the up-timers. It is the day of their independence from the English."

***

Douai, Flanders

July 4, 1636

Von Spee had to have a sharp discussion with Midas about dogs not being allowed in the sanctuary. Midas finally grudgingly lay down at the door from the sacristy to the altar and the pulpit. "Now just wait for me, Midas," he said. Midas turned around in his own length and gave von Spee his tail.

Von Spee shrugged, and went through the door, closing it behind him. There were wires all over the pulpit as they got ready to broadcast his sermon. A middle-aged Jesuit brother came up and said, "I am Brother Sebastian. We are almost ready for you, Father. We need you to do a voice check."

Spee stood in the pulpit and recited the Lord's Prayer until Brother Sebastian said, "That's good, we've got voice. Are you ready, Father?"

"Yes, I am ready," von Spee said.

"You know that there may be some dispute, Father," Sebastian said.

"Yes," said von Spee, "I confidently expect it."

The seminarians filed into the old wooden pews. Many were blond or redheaded, with fair complexions, but others were olive-complected and two were black. They were all dressed in simple seminarians' black cassocks and wore sandals on their feet. They stirred and made the usual noises a crowd makes as they got settled down. Then the older Jesuits entered, came down front, and sat in the front pews. The sun beamed in, parti-colored through the stained-glass clerestory windows, and the church had a huge rose window behind the altar that glowed as the afternoon sun illuminated it.

Von Spee recognized several of the older Jesuits, aside from Father Matteus. There was Laurenz Forer, a foremost controversialist. He was a short, wiry man, with a spray of white hair sticking up around his head. His eyes were beady and focused on Spee. Herman Busembaum, from whom Spee had taken a course in theology, sat next to Forer. He was everything Forer was not—big, imposing, with a good-humored smile as he acknowledged Spee's glance. On Forer's other side sat Matteus Arrostegui, the master of seminarians. At the end of the pew was Francisco de Lugo, a Spanish Jesuit, his body language very closed, his arms wrapped in the sleeves of his cassock. There were several other Spanish and Portuguese Jesuits in the audience.

Brother Sebastian waved a hand. He had a small microphone, and he spoke into it. "Welcome to the Voice of Saint Ignatius, coming to you from the Jesuit College at Douai in Flanders. Today we will hear from Father Friedrich von Spee about the last days of Pope Urban VIII."

Von Spee waited, and when Brother Sebastian's hand went down, he began to speak. As he had learned to do in Magdeburg, he spoke slightly slower than his usual speech.

"I have decided to give this sermon in English," Spee said. "Since this is the college that produces Jesuits for England, most of you speak it well enough to understand, and since this is being both recorded and broadcast, I want to use a vernacular language."

There was silence, but several of the older Jesuits looked at each other sharply.

"I am commanded by the Father General of our Order, Muzio Vitelleschi, to give you this account of the last days of Pope Urban VIII. If you have not yet heard, Pope Urban was assassinated by agents of Cardinal Borja and the Spanish Crown . . ."

One of the Jesuits, Laurenz Forer, jumped up. He was short, and he stood on tiptoe and leaned forward, clutching the front of the pew, "How do you know that? Perhaps it was all an up-timer plot! Cardinal Borja would never do a thing like that!"

Von Spee calmly said, "We know because we found the assassin and the documentation. It is clear that Borja is guilty of having the pope murdered, as he also did for thirty of the college of cardinals. There simply is no doubt."

Forer sat down, muttering darkly to Arrostegui, his neighbor in the pew. Arrostegui whispered back and patted Forer's hand in a calming gesture. Forer shook him off, glaring.

"But let me continue," von Spee went on. "The assassination took place just after the ecumenical conference in Besançon in May, where the pope revealed the major points of a papal Circular to be sent out immediately. Because there were nearly fifty of the members of the college of cardinals there in Besançon, they immediately went into conclave. With his dying words, Pope Urban had named his preference for a successor, and the college of cardinals agreed, naming Cardinal Bedmar as the new pontiff. His reign name is Fabian II, and he has taken up residence in Lille, just north of here, so that he will be out of the influence of any court."

It was deadly quiet in the church. Von Spee could see the faces of some of the seasoned Jesuits becoming angry, and yet others were thoughtful, and still others mirrored their confusion as the news overtook them.

"After my sermon," von Spee said, "we will have a service of remembrance to pray for the soul of Pope Urban, and for the health and recovery of Father General Vittelleschi who was also struck by the assassins. He is recovering and is expected to return to good health."

Von Spee looked at each of the older priests in turn. "I want to make it very clear," he said, "that the Father General has made his vows to Pope Fabian, and as Jesuits, we are bound by the vow of personal service to the pope. That pope, as Father General has declared, is Pope Fabian. There is no other!"

"But we are here to listen to the last words of Pope Urban, whom we all knew as a worldly man, a man more interested in Earthly pomp and power than in sanctity and good works. Yet nothing could be farther from the truth at the end of his life."

"Pope Urban said, 'At this late hour, I have finally heard His Son's words. And among them were these: 'If a man has a hundred sheep, and one of them has gone astray, does he not leave the ninety-nine on the mountains and go in search of the one that went astray? And if he finds it, truly, I say to you, he rejoices over it more than over the ninety-nine that never went astray.' Are we to slay the lost sheep? Or are we to accept Christ's teaching: that it is greater to love the wayward of the flock, and to preserve them? And their children, in all their multitudes.' "

Spee said, "Then Pope Urban said, 'This, this, is why we are gathered here in the name of ecumenicism: to stop the slaughter of the sheep. To call them back, that they might come as close as they can.' "

Von Spee paused, and then said, "The Holy Father said that he renounced the use of the word 'heretic.' Our pontiff said, 'That is a promise to which you may bear witness, and of which I encourage you to make wide report. You will not hear that word emerge from my mouth this day, or any following, for as long as I shall live. And as regards the 'ties of faith' we share: I not only presume that they are different; I presume that we are entitled to those differences. They are the manifestations of the free will which our Creator has created in us. It is no man's place to compel another to change what is in another's heart. For Christ told us, "Judge not, lest ye be judged." '

"And then"—Spee paused for a breath—"His Holiness proclaimed that canon law shall no longer be silent upon, or easily interpreted to allow, waging war upon fellow Christians, or killing persons simply because their faith does not make them, by our definition, 'believers.' "

Von Spee's voice, the voice of a trained singer and songwriter, rang out. "Pope Urban asks us, 'When did God ever command us to kill for him? Instead of instructing us to kill, or persecute, or torture, what did Our Savior teach us? To turn the other cheek. To wash the feet of those society deems our inferiors. To love others as ourselves. To bear in mind that the last shall be first and the first shall be last. And to love one another in honor and imitation of the way God loves us. How can even the most tortuous of exegeses of those teachings extract any validation for an exhortation to kill our neighbor, to persecute him in the name of righteousness, and to torture his body so that a recantation of heresy might be extracted by pain? No. These things—these earthly horrors—we must reject.'

"Many things had changed in the centuries the Church weathered before the village of the up-timers was sent to us," von Spee went on. "In the years from 1936 to 1945, at least twenty million—yes, million, you heard me right—of our brothers and sisters who were Jewish, Romany, Lutheran, Catholic, and of no faith at all were herded into special camps and murdered, just for being who they were. The Church did not speak out as strongly against this as it should have, and one of the things that the Second Vatican Council, about which you have heard, decided was that the Church had to be about in the world, to right such wrongs."

The church was so quiet it was like nobody was even breathing. Spee went on, "In a spirit of reconciliation, in the years just prior to the Ring of Fire event, the current up-time pontiff, Pope John Paul II apologized for Catholics' involvement with the African slave trade. Too many Catholics participated in that heinous endeavor. The up-time pope also apologized and asked God's forgiveness for the Church's role in burning persons at the stake and the religious wars that followed the Protestant Reformation"—a startled rumble arose from both the seasoned priests and the seminarians—"for the injustices committed against women and the violation of their rights as human beings, for the denouncement and execution of Jan Hus in 1415. This pope from up-time further apologized for Catholic violations of the rights of ethnic groups and peoples, and for showing contempt for their cultures and religious traditions, and for the Crusader attack on Constantinople in 1204. Pope John Paul II also apologized to the followers of Martin Luther, saying Luther had been correct in the matter of indulgences and other things."

Father Forer surged up from the pew and shouted, "Are we all to become Lutherans now? No! Never, I say!" He was shaking, and his face was bright red and contorted in rage. His seat mates shrank back from him in the pew.

Von Spee overrode Forer's shouting. "You are a man under orders." Von Spee pointed his finger at Forer. "Your General has said that Urban was correct, is correct, and his successor, Pope Fabian, agrees. Sit down. Curb your pride! And listen!"

Forer sank into the pew, gabbling. Arrostegui patted him calmingly.

Spee went on. "The words of Pope Urban are a challenge to us, as the Church. 'What we can do, what we must do,' Pope Urban said, 'is to resolve ourselves to be ready to embrace the change that is coming. But if we have been too long burdened with the cares and woes of this globe's flock to trust in the possibility of a new future in which our faiths cleave closer, then here is a reason rooted in the very dirt and mud of this material world. You may save lives. You may call for tolerance where there has been none knowing that, elsewhere, the rest of us are doing the same. You may insist upon fair treatment of all God's children, no matter their origins, knowing that similar exhortations are arising, not merely as a matter of individual conscience, but as a collective resolve to make this the bridge by which we shall ultimately reach each other to join hands. How many fields have been littered by the bodies of the Lord's own sons and daughters, blessed and cherished all, in His eyes? How many have been made homeless by those wars and now lie starving at the margins of fallow fields? And how many uncounted millions in the years and decades and centuries to come might feed the insatiable maw of this religious strife again and again and again—all of them chanting battle cries that it is their obligation to fight—and that the carnage is justified—because 'God is on our side'?' "

Von Spee paused and let the silence build. Then he said, "The Holy Father taught us this. 'The path through the door that leads from war and misery to peace and hope, stands open before us. Not merely as individuals, but as the mystical body of God's own Church, each of whom may communicate with and support the others on a daily basis, no matter how many miles separate us. You only need to choose to go through that door, but you will need to do so on your knees, humble before both God and man.'

"This is the way we will go forward as a Church," von Spee said firmly. "In humble heart, and on our knees. Remembering all the while that Our Savior was scourged and spat upon, beaten and nailed to a cross to save us all. Pope Urban, who certainly will be named a saint, calls us to this service. He went through the door of the heart on his own knees. How can we not do the same?

"In the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, this sermon is ended. Take the words of Pope Urban into the world with you in your hearts." Spee bowed his head, crossed himself, and turned, but before he left the pulpit, several members of the audience accosted him. Brother Sebastian made cutting motions with his hands trying to shut off the broadcast before it got out of hand.

Father Forer walked up to the altar rail and pushed his face up to von Spee, who came down the steps of the altar to meet him. "You are wrong!" He poked his finger into von Spee's chest. "Urban was wrong! He was under the influence of that Satan's spawn, the up-timer Mazzare! If Bedmar thinks he is the pope, well he is wrong too!"

Forer drew himself up to his full height, coming barely to von Spee's chin. "I refuse to accept Bedmar's election and this contrary canon!" Before von Spee had a chance to do more than open his mouth, Forer turned and stormed off, with some half-dozen Jesuits following after, nearly all of them Spanish or Portuguese. Father Matteus, who had been standing near von Spee, looked after them and shook his head.

"It will take some time for some of them to realize that the pope was right," Matteus said, "and that we have been given a miracle to bring us to that door on our knees."

"I must go and prepare for the remembrance service for Pope Urban." Von Spee turned to go.

"Excuse me, Father." One of the two African seminarians that had been in the audience stopped him and said, "Could Diogo and I have a word? I am Symao de Luanda, and this is my compatriot and brother in faith, Diogo Diosdedo."

"Yes?" Von Spee composed himself to listen. Thirty years of working with young men, students and seminarians, had taught him that they will say what they need to when they need to, and rushing them generally confused them.

"Did I hear correctly? That the Church will actively come out against the African slave trade?" Diogo looked very tentative, almost frightened.

"Yes, the papal circular has a specific stricture against slavery, the slave trade, and owning enslaved persons, just as the papal bull Sublimus Deus of Pope Paul III did a hundred years ago," von Spee said, curious. "Why do you ask that?"

"Because I was a slave!" Diogo cried out. "And because the Jesuits all hold slaves. They do it in both Angola and Congo and in Brazil, and they buy and sell them so they don't just own us, they trade in our lives."

"You know this for certain?" von Spee asked.

"Yes." Diogo was visibly shaking. "Because I was a slave and I was owned by the Jesuits at the seminary and church in Luanda itself. In fact, the head of the seminary in Luanda was Father Luís Brandão and he used to say to us often that 'slavery was a positive benefit to the slaves since it brought us closer to God.' It wasn't until they realized I could read and write and had some education that they decided to free me, as long as I chose to become a Jesuit. So, that is what I did."

Von Spee stopped as though poleaxed. His eyes blinked, not seeing. He could not believe what he had heard. His hands became fists, his mouth pursed. "This, this we must change!"

Diogo nodded, first tentatively and then vigorously. "Yes, Father, yes!"

Von Spee looked at Diogo with compassion. "And are you happy with your vocation, after all this, my son?"

Diogo rubbed his fingers through his short and wiry hair. "Yes, Father, I am. Especially now that I have heard what you said. Now, when I am ordained, I can ask to go back to Angola and preach against slavery and work for the betterment of my people."

"And what about you?" von Spee turned to Symao, who had been standing there quietly.

"I met Diogo in Luanda when he was just freed. He was near helpless from what he had been through. We have been like brothers from another mother ever since. Where Diogo goes, I need to go—so I can keep him safe." Symao's face shone and he grinned broadly.

"We were talking, Father von Spee, Diogo and me," Symao said. "You are the one who wrote the Cautio Criminalis that has ended nearly all witch trials and burnings?"

"Well, it was supposed to be anonymous, but I guess the word somehow got out. Yes, I wrote it. Why?"

"We thought you might write something similar against slavery."

Friedrich von Spee stood as if slapped. Involuntarily he began to kneel in front of the two African seminarians. How much more did he need Pope Urban to show him his way forward? Here once again he was being given an opportunity to go through the door on his knees.

"I will think about how I could write it," he said. "Contra Servitutem. 'Against Slavery.' It has a nice ring to it."

***

Lille, The Netherlands

July 5, 1636

Father Friedrich von Spee took a clean sheet of paper. He signed himself with the cross, and prayed, "In the Name of the Father and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, Amen." At the top of the paper he wrote the initials every Jesuit heads every document they write with: A.M.D.G. Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam—to the greater glory of God.

"For a hundred years," von Spee wrote, "The Church has condemned the institution of slavery in the New World, and in the Old. Enslaving indigenes in the New World and enslaving Africans and bringing them to the New World, has been denounced by popes for a century, starting with Pope Paul III's bull Sublimus Deus in 1537, and continuing through the work of the Jesuit Father Peter Claver (who the up-time church would quickly canonize after his death), and the most recent writing of the late Pope Urban VIII. According to the up-timers, Urban would have written against slavery in a bull entitled Commissum Nobis that would have been issued in 1638.

"It is time, and more than time," von Spee continued, "that men and women of good will should band together in opposition to the practice of enslavement, whether it be of indigenous Americans, or of persons of African ancestry who are dragged from their homes, chained together, shipped like so many logs to the New World, and forced to labor until their deaths.

"It is time for the governments of Europe to give the Anti-Slavery League support, not just words but strong action to back up its mission of the eradication of enslavement throughout the world, wherever it may be found. "

Von Spee sighed, and petted Midas, who'd insinuated his head under von Spee's hand. "What do you think, silly old dog?" Midas barked once. "You agree, do you? Very good dog!"

***