CHAPTER 3

The Giant Telescope

IT was not until several months later that my father was permitted to go ahead with his work. Naturally the first thing he did was to show me the result of his lifetime of labor in the mountains. It was a cool evening in early fall when I received my first glimpse of the 1200-inch lens, the “Eye of the World,” as father had named it. It was located inside a circular brick building on the flat summit of another peak, about a mile away. He decided not to go over to it that evening; but at sundown he would show its operation to me from the observatory on our own summit. He gave me a pair of binoculars and asked me to watch the cylindrical building, while he entered the observation car. As he explained it, the huge lens and mirror were moved by motors located in the lens-house, for which the control switches were in the observation car, which will be described later. He began manipulating the switches and the entire side of the lens-house facing us parted in the middle and swung open like two doors. Similarly, the roof opened and moved down over the sides of the building, out of the way. The giant lens now rose above the walls, looking like a vast flat dome that could have served as a roof for the entire structure. The dying rays of the setting sun were mirrored in its convex surface, making it an object of rare beauty. He then swung the glass over on its edge, showing me its massive circumference. It turned back slowly until its edge was facing us, and I could not but marvel at its thinness. The steel rim around the edge was all that was visible in the gathering dusk. Father then called my attention to a large plane mirror, located below the lens, and explained that the rays of light from the star under observation passed through the lens and struck the mirror, which was automatically tilted to the proper angle to throw the rays across the valley and strike a certain point where the eyepiece was located in the observation car. The mirror was moved by separate motors, which worked from the same switch, and were synchronized with the machinery for moving the lens. This made it possible to keep the mirror automatically tilted at the proper angle.

A small telescope, a range finder, was used to locate the star to be studied and mark its position in degrees of altitude above the horizon and its direction from the zenith. The giant lens could be turned to this position and the clockwork mechanism started; which moved the lens slowly, as the earth turned on her axis, following the path of the star across the sky and keeping it under observation.

To demonstrate how it worked, father directed the lens toward Vega, who was almost at the zenith. He said we would not need an eyepiece to observe the effect with this giant star. As the lens moved into position, the mirror became brighter and in a few seconds the concentrated rays from Vega were focused into a narrow beam of light, almost as bright as sunlight. It was the most amazing thing I had ever seen! It was almost impossible to believe that this narrow pencil of bluish white sunlight was coming from a giant sun a hundred and sixty million million miles, or twenty-seven light-years away!

As the telescope had not been used for some time, father thought the lens must be too dirty for satisfactory observation that night. Consequently, he manipulated a few switches, which caused the lens to drop into position. Then he replaced the roof and closed the doors.

The next day we drove over to the lens-house for a closer inspection of the “Eye of the World.” He unlocked a door which led into the large room where the lens hung suspended in its closed position about ten feet above the mirror, which lay flat on the floor. A thin coat of dust covered lens and mirror; so the first task was to clean both. He pressed a button on the wall and a huge iris shutter, resembling the shutter in a camera, slowly began to close. Within a few minutes, it had closed and now lay between the lens and mirror. The purpose of this shutter was two-fold: it could be used for stopping down the lens when too much light was passing through it and it made an excellent platform upon which he could stand while directing the cleaning and polishing the lens and mirror. The lens cleaner was a clever device which acted as a vacuum cleaner, dust mop and lens polisher at the same time; with the aid of levers that could be extended to any desired length, it could reach any part of the surface of either lens or mirror. It required but a little less than two hours to clean and polish the mirror and both sides of the huge lens.

He next showed me the motors and mechanism for moving the lens and mirror. I shall not attempt to describe them, further than to say they were complicated; too complicated to study them out and learn the use of each part at this time. I was more interested in knowing how this great piece of glass had been made.

As father explained, he had first conceived the idea for this telescope while a student at Harvard. Everyone to whom he mentioned the idea had discouraged him, except his father, who realized that the science of light and optics was a deep one, the surface of which had only been scratched.

In an attempt to learn the secret for making the superior French lenses, he stumbled upon a formula that produced a glass superior to the French product. This “Brewster glass” proved to be a speedier lens than the later-to-be-discovered quartz glass. It also had the strange quality of being entirely free from practically all chromatic abberration; hence it was not necessary to use a compound lens of both crown and flint glass, each to correct the faults of the other. The Brewster glass was very easy to work. A lens could be broken in two pieces and fused together again, without the place showing where they were joined. A lens could be made in two or more sections and fused together; making it impossible to distinguish it from a lens made in one single piece. This made the construction of the “Eye of the World” possible.

He found that his glass was immune to moderate changes in temperature; a variation of sixty degrees was necessary before any distortion was noticeable. To guard against atmospheric interferences, so disastrous to large telescopes, he decided to build it in the moun-tains-.of Arizona, where the dry climate and atmospheric conditions were most favorable. A large lens and a long focal length made it possible to obtain a maximum of light, while the iris shutter permitted him to use only the desired amount of light to obtain the best results.

Building the “Eye of the World”

A YEAR or more was spent in making plans tor the observatory. The size and thickness of the lens, as well as that of the various eyepieces, were calculated to an exactness; when he was ready to begin work on it, he knew exactly what he was going to do. Another year was spent in finding a location that met his requirements: two mountain peaks, the proper distance apart, with one, upon which the lens-house was to be built, exactly north of the observatory summit. When the location was found, he gave a contract to a construction company to build the lens-house, which was to be used at first as a factory in which the “Eye of the World” was to be constructed. He also had erected another large building, in which he expected to house his army of workers while the observatory was being built. Many problems were encountered, among which was the difficulty in moving supplies up the mountain side. A roadway had to be constructed and thus two more years passed before the construction of the buildings could be started.

Then he went to Paris and returned with twenty of the foremost lens makers in France and their families. Nothing but the highest of wages could induce them to come to the wilds of Arizona and stay away from civilization until the telescope was finished. It was during this period, that my mother died and I was born.

The lens was not cast in one piece, but in over eleven hundred sections, each of which was thirty-six inches in diameter. These sections were hexagonal in shape and fitted together like cells in a honeycomb. Each was cast in a separate mold, ground and polished to an exact measurement and fitted and fused in place, giving the finished product the appearance of being cast in a single piece.

It sounded simple when father explained it, but it had been a long and tedious task. Many times he felt like giving up in despair; but only that iron will and bull-dog determination, “The Brewster Grit,” kept him going during the long years. But at last, after twelve years the “Eye of the World,” on which twenty million dollars had been spent, was finished. It was the largest and most expensive piece of glass in the world—and, as yet, no one could tell whether it could ever be used in a telescope or not.

The large mirror presented the next difficult task. It was essential that the glass used in the mirror should not show even a microscopic variation in thickness. Ten car-loads of special plate glass were brought up the mountain, before there was found thirty thousand square feet of perfect glass from which the gigantic mirror, two hundred feet long and one hundred and fifty feet wide, was made. The mirror was made in 300 sections, each ten feet square, which were fused together and silvered, making the largest mirror in the world. This big piece of glass could not support its own weight; so a flat metal support was placed under its entire area.

While the lens and mirror were being built on the site where they were later to be used, lens makers in Paris were making the set of thirty separate eyepieces, according to specifications and measurements furnished by my father. Each eyepiece produced a different degree of magnification; the most powerful would show on the moon an object as small as a human being, but the field of vision was quite small. Another set of lenses, the other extreme, would show a larger surface of the moon, but the magnification was proportionately lower,

The next difficult task was the construction of the machinery for moving the lens and mirror and holding them in position. This was designed and installed by a staff of mechanical and electrical engineers from Chicago. It was impossible to manufacture the equipment in the mountains; so it was shipped to Brewster and a fleet of motor trucks was worn out in moving it up the mountain. Six more years passed before the machinery was all in place and a high-tension line was erected to supply the motors with electrical energy from Phoenix, ninety miles away.

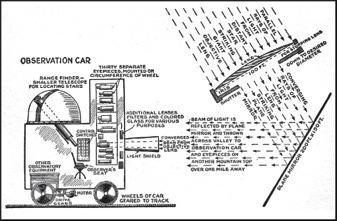

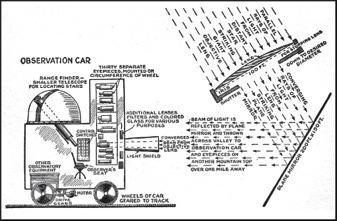

When we returned from the lens-house, father showed me the observation car and the eyepieces. The car was a building on wheels, which were geared to a straight track full of fine cogs, extending toward the lens-house. The cogs in the wheels of the car meshed perfectly with the cogs in the track, making it possible to gauge the distance from the large lens accurately by the revolutions of the wheels. Upon entering the car, the first thing I noticed was a large wheel, standing upright across the center of the car, upon whose circumference were thirty complicated sets of lenses, comprising the various eyepieces. Father asked me to sit down in the observer’s seat and pull the nearest lens into position. As I did so, the car moved slowly forward. I turned the wheel and another eyepiece came down and locked in position, while the car moved slowly forward and stopped at the proper position for that particular lens. Each eyepiece worked at a different distance from the objective lens and the movement of the car on the track was equivalent to the shortening and lengthening of the tube of smaller telescopes. The electrical engineers had arranged a device by which the car would move to the proper position and stop of its own accord, when the lens was in position.

After examining the eyepieces, father next showed me the switchboard for controlling the motors that moved the lens and mirror. Each switch was plainly marked, and their use was quickly learned. He next directed my attention to the spectroscope, astronomical camera and other observatory equipment, with which I was already familiar.

A light-shield on the exterior of the car was the only thing I had not examined; its purpose was to keep outside interfering light from striking the eyepiece. It consisted of a black metal tube, about twenty feet long, pointing toward the lens-house, just in front of the eyepiece. It was all that was required to take the place of the tube of a smaller telescope; as its only purpose was to shield the eyepiece from outside light.

Roaming the Skies

THE warning of Dr. Zeilars was entirely forgotten that night. The telescope was ready and the sky was full of stars waiting to reveal their secrets. Father’s cited enthusiasm was enough to make one think he had just bathed in the Fountain of Youth. He ran about the car explaining first this device and then that, so rapidly that I utterly failed to understand half of it. He was warning me about looking at bright stars— “If you are not careful, you will be blinded by their intense rays. When their maximum light is received there are twenty stars that in the telescope appear almost as bright as the sun does to the naked eye. There are about a hundred more that will hurt your eyes. Always open the iris shutter slowly when looking at a new star. Sit down here in the observer’s seat and I will tell you every move to make.”

Trembling with emotion, I obeyed. Here was the moment we had both been awaiting for years. The greatest desire of our lives would presently be realized—when the eyepiece before me would become a window, through which I could look and learn the secrets of the skies. The moment was so dramatic, so full of expectancy, that I hesitated to touch the first switch. To father, it was a common occurrence; but to me it was a sacred rite. The heavens were about to declare the glory of God and the firmament to show His handiwork.

Under father’s direction, I swung the lens toward the Great Nebula in Andromeda. Beginning with the weaker, lenses, I increased the magnification until the nebula was resolved into stars of varying degrees of brightness. It was so far beyond the limits of the Milky Way that it was distinguishable as a separate island universe like our own, full of brilliant stars—but just another molecule in the vast cosmos of outer space. I next pointed the glass toward the Milky Way and a thick group of great sun-like stars dazzled my view.

With the enthusiasm of the novice I roamed the heavens looking at a hundred interesting stars and nebulae, but one for never more than a minute at a time. As soon as one was located, I began searching for a new world, a star to add to my list. Father never objected to my using the telescope in this manner. He thought it would be an excellent method for me to learn the use of the controls; as there would be plenty of time in the future to make an exhaustive study of individual stars. But the last thing I noticed before going to bed, was a silvery light in the east, heralding the rising of the moon. I waited until my old friend floated above the horizon; she had already entered her last quarter and I was sorry that two weeks must pass before she would be high enough in the evening sky to reveal her secrets.

After a few nights, Father decided that I was capable of handling the telescope by myself. He was to do his sleeping at night while I was in the observation car, and remain awake in the daytime. I was too interested in the distant stars and nebulae to think of sleep during the night.

One evening while watching the sunset, I decided to sing a song that had long been a favorite of mine: “Beyond the Hills is the Sunrise.” It may be superstition or just a sequence of coincidence, but I always imagined that something important was sure to happen when that song was in my mind. And something usually did.

The sunset was more than beautiful—it was sublime. The sky was clear and cloudless and the brightness of the sun was but slightly dimmed as he neared the horizon. Amazed at the unusual beauty, I continued singing as the sphere reddened and slowly dropped behind a distant snow-capped range. Suddenly, I saw something else in the sky that almost startled me—a thin crescent of light, like a delicate shaving of the purest gold from some titanic workroom. It was the new moon, so shy and so new in the evening sky as to be almost invisible. Never before had the moon seemed more beautiful; never before was I more pleased to see my old friend.

Now I was desperately eager to see her. But there were preparations to be made first. The clockwork mechanism was now arranged to synchronize the movement of the lens and mirror with the path of fixed stars across the sky. But in her orbit around the earth, the moon travels more slowly in her nocturnal journey across the sky. It was necessary to lower the weight of the huge pendulum of the clockwork and thus slow down the movement of the lens until it was synchronized with the apparent movement of the moon. I calculated the speed of the moon across the sky, estimated the amount it was necessary to lower the pendulum and submitted my figures to my father.

“You have the right idea,” father replied, “but you have forgotten something. You know that the moon increases her speed in her orbit as she approaches the sun and decreases it as she passes from new moon to full? You will find it necessary to lower the weight or raise it as the occasion requires. You will find complete directions pasted on the door near the clockwork, in the lens-house. You will also find it necessary to clean the lens and mirror every day, while studying the moon with a powerful eyepiece. You will find the surprise of your life when you first receive a close-up view of the moon.”

“What is it! Is the moon inhabited! Is there really enough atmosphere to support life?”

“For all I know, the little worlds in vast space between the planets are inhabited too. I have found life on the moon and all the planets that I have examined. But it is not exactly the same forms of life with which we are familiar. Evolution, working with different materials, under different conditions, has produced different results. Terrestrial life is not duplicated elsewhere.”

“Can life be found on all parts of the moon? Or is it confined to particular regions?” I asked.

“Most of the surface of the moon is desert land, but look at Mare Crisium if you want to see the Selenites.”