Introduction

I Am an Avatar

by Ray Kurzweil

“I was smitten. I never wanted to leave this world, one more beautiful than I could have imagined,” recalled a woman who recently had her first full immersion experience in October of 2016 in a multiplayer VR world called QuiVr. “Virtual reality had won me over, lock, stock and barrel,” she continued.

Her epiphany was short-lived as the virtual hand of another player named BigBro442 started to rub her virtual chest.

“Stop!” she cried. But his assault continued and intensified.

“My high from earlier plummeted,” she wrote. “I went from the god who couldn’t fall off a ledge to a powerless woman being chased by another avatar.”

Finally, after being chased and harassed around the virtual cliffs and ledges of the QuiVr world, she yanked off her headset.

I had several reactions to reading about this incident. First, dismay at the pervasive misogyny and harassment directed at women which is only intensified in the anonymity of many virtual environments and other forms of online communication.

The other reaction is especially relevant to this book. I have written that virtual environments are inherently safer than real ones because you can hang up if the experience is not going to your liking. Indeed, she did ultimately leave the QuiVr world, but a week later wrote, “It felt real and violating … the virtual chasing and groping happened a full week ago and I’m still thinking about it.”

Putting aside for the moment the important issue of harassment and assault in both real and virtual spaces, this incident illustrates a key lesson about the increasingly virtual world we will be inhabiting: we readily transfer our consciousness to our avatar.

Like a child playing with a doll, we maintain some level of awareness that the virtual world is ever so slightly more tentative than the real one, but we have little resistance to identifying with our virtual selves. I have always felt that the term “virtual reality” is unfortunate, implying a lack of reality. The telephone was the first virtual reality enabling us to occupy a virtual space with someone far away as if we were together. Yet, these are nonetheless real interactions. You can’t say of a phone conversation, “Oh that argument we had,” “That agreement we made,” “That loving sentiment I expressed,” that wasn’t real; that was just virtual reality.

We have now had several decades of experience with avatars representing us in virtual environments and these are now becoming immersive with 360 degree three-dimensional virtual environments. Of even greater significance, however, is that we are now embarking on an era in which avatars will also represent us in real reality. That is the subject of this compelling and creative collection of stories compiled by Kevin J. Anderson and Mike Resnick.

A major issue concerning avatars in the real world is the phenomenon of the uncanny valley, which is the sense of revulsion that occurs if a replica of a human (whether a computer-generated image or a robot) is very close to lifelike, but not quite there. Thus far, we have largely stayed on the safe bank of this valley. In the movies, computer-generated actors such as Shrek are decidedly not trying to look human. This is beginning to change. In the 2016 Star Wars movie, Rogue One, Grand Moff Tarkin, the Imperial leader of the Death Star, was computer generated due to the death in 1994 of Peter Cushing who played him in the earlier Star Wars movies. For me, he was in the uncanny valley and looked creepy, but not everyone agreed. Many critics applauded how realistic he appeared. Thus, we’re approaching the safe bank of the uncanny valley when it comes to animations. There will always be controversy as we get close to full realism.

However, when it comes to robotic avatars in the real world, we’re not yet approaching the uncanny valley. I’ve given multiple speeches using a technology called the Beam Robot, which is a simple human-sized device consisting of a wheeled base holding a display of a person’s face at a normal face height. As a user, I can roll out on stage after I am introduced and give my talk, and then mingle with the audience afterwards. There are significant limitations in that I am always afraid I am going to zoom off the stage as I cannot see where my virtual bottom is. When mingling, I cannot shake hands or give and receive hugs. Nonetheless, I do feel like I am at the venue and am able to put these restrictions temporarily out of mind.

Over the next five to ten years all of these limitations of robotic avatars will gradually dissolve, just as fully virtual environments have gone from the simple worlds of Atari 8-bit games to the compelling three-dimensional virtual environments of today. As we do so, however, we will need to be wary of the uncanny valley.

I’ve described one way to leap over the uncanny valley in an issued patent titled “Virtual Encounters” (U.S. Patent Number 8,600,550) that will allow you to hug and otherwise physically interact with a companion in real reality even if you are hundreds of miles apart. If a third party were to witness such an interaction, they would see each party with a robotic surrogate. However, for the participants, neither party actually sees the robot they are with. Instead, they experience their human partner.

To envision this, let’s call the two parties John and Jane. John sees out of the eyes of the robotic surrogate with Jane, and similarly, Jane sees out of the eyes of the surrogate with John. They hear out of the ears of the surrogates and feel (using tactile actuators such as piezoelectric stimulators on their hands, arms and other body parts) the physical sensations detected by the physical sensors on the surrogates. The physical movements of the two human participants direct the movements of the corresponding robotic surrogate. So each party feels like they are with their human partner and does not see or detect the presence of any robots. Given our readiness to transfer our consciousness to avatars that represent us in another environment, both parties feel like they are truly with their human partner. Once perfected, it would be just like being together. The two robotic surrogates are simply a communication channel incorporating all of the senses. This concept can be extended to more than two participants.

The scenario described in this patent is one approach to being somewhere else using avatar technology. Another approach is to transfer ourselves to remote robotic substitutes that will appear real to other real people in a real environment. Through accelerating advances in robotic, sensory, communication, and virtual reality technologies, we will be able to instantly exist in multiple places at once and overcome the limitations of today’s state of the art.

The latest XPRIZE, called “Avatar XPRIZE,” envisions “limitless travel by teleporting one’s consciousness into a physical avatar body that will enable people to instantly be in multiple places at once, literally.” I worked on this prize with Harry Kloor, who led the effort.

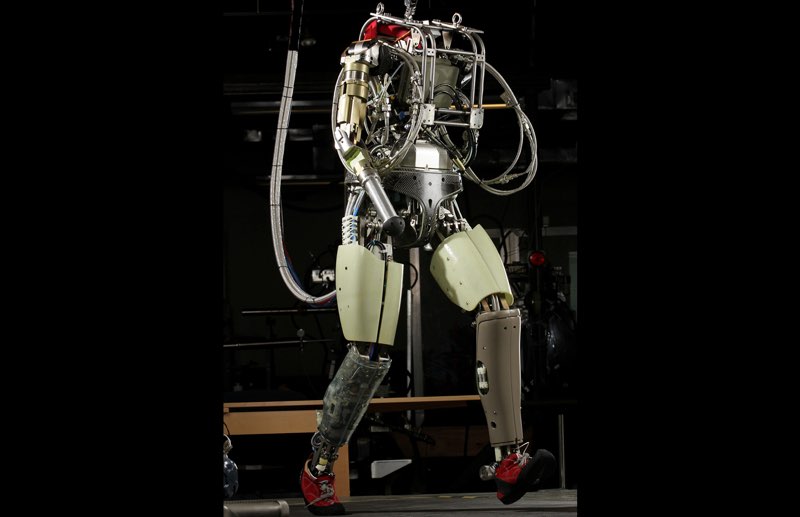

The technologies to realize this vision are rapidly coming into place. Start with today’s Beam robot and replace each of its components with technologies that are already coming into place. For example, replace its wheeled base with walking legs, a capability that Boston Dynamics and a number of teams have already demonstrated.

Robotic walking legs by Boston Dynamics

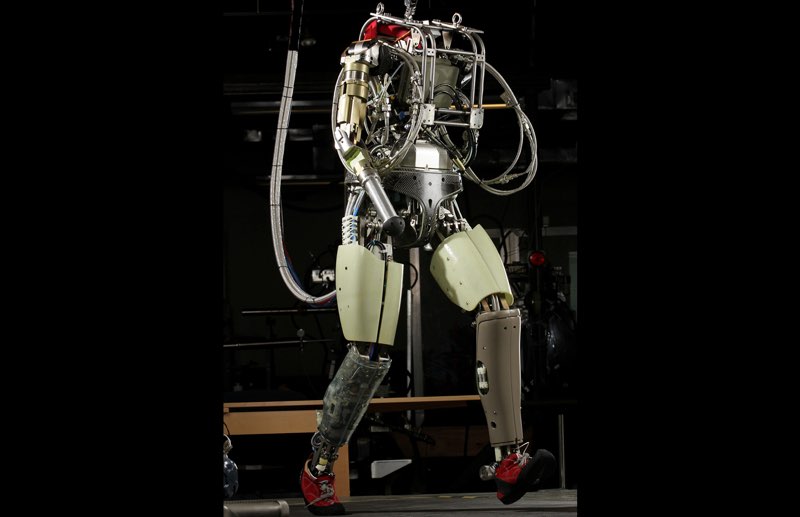

Now add robotic arms that you control with your own arms, another already available technology demonstrated, for example, by Dean Kamen’s “Luke Arm,” which is intended as a prosthetic for amputees. This technology has already received FDA approval based on its ability to allow users without biological arms to “prepare food, feed oneself, use zippers, and brush and comb their hair.”

Mr. Fred Downs using a prototype of the LUKE arm developed by DEKA Research & Development

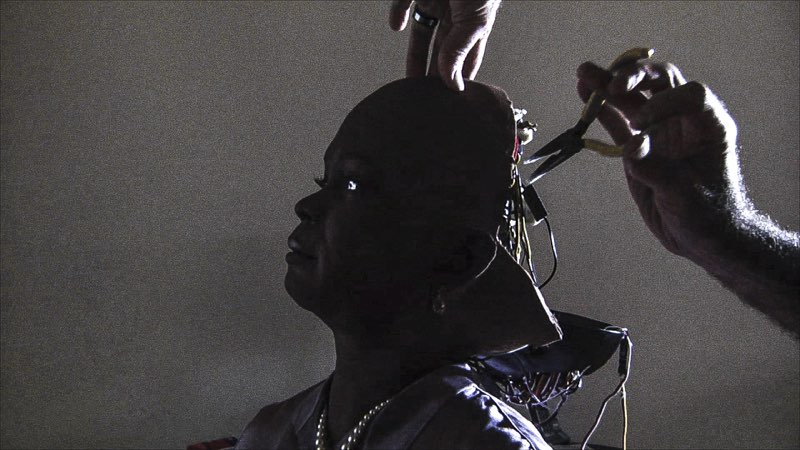

Replacing the avatar’s head with something realistic is the most challenging aspect of the Avatar XPRIZE, but consider this robotic head created by communications and biotechnology pioneer Martine Rothblatt, in collaboration with Hanson Robotics Ltd., called “Bina48,” based on Martine’s wife, Bina:

Martine Rothblatt and Hanson Robotics Ltd.’s Bina48 Robot

Bina48 is able to respond to questions using its own AI, but it could also be used to project the presence of an actual human.

In five to ten years, these types of technologies will be perfected and seamlessly integrated into an avatar technology that will enable us to do virtually all of the things we do now by traveling to a different location. They will be designed to look and feel human. We will then be able to prepare and serve a meal, subsequently clean up the table, mingle with guests, hug and kiss a friend, perform rescues, conduct surgeries, engage in sports competitions, and do a myriad of other tasks just as if we were there.

And as a result of the fifty percent deflation rate that is inherent in all information technologies, this capability will ultimately be inexpensive and ubiquitous. Consider that your smartphone is literally a trillion dollars of computation and communication, circa 1965, yet it costs only a few hundred dollars today and there are now two billion of them in the world.

The stories in this outstanding and highly imaginative volume bring these diverse scenarios to life. In Kevin J. Anderson’s “The Next Best Thing to Being There,” a robotic sherpa guides climbers on Mount Rainier, which illustrates one important application of robotic avatar technology, which is bringing remote expertise to challenging environments. Francesca, the wife of one of the climbers, is experiencing the climb virtually through the sherpa avatar and shares the shock of the actual participants when an avalanche suddenly strikes. As the ensuing crisis develops, the avatar takes on a different role, which is as a remote physician attending to the injured climbers, and directed by doctors far away.

We already see doctors performing virtual surgery using avatar technology. For example, a human doctor remotely doing eye surgery by entering a virtual environment in which the patient’s eye becomes as big as a beach ball, thereby enabling the intricate surgical maneuvers required. Surgeries can now be performed by doctors who may be thousands of miles away, allowing medical expertise to be instantly transported to remote areas where medical services are scant.

In Tina Gower’s “The Waiting Room,” a woman whose physical body has failed her is able to explore the world and seek a relationship with her children by using an avatar that represents her in a physical reality that she would otherwise not be able to navigate with her physical body. Not only does the protagonist of the story successfully transfer her consciousness to her avatar, but we the reader do so as well. We readily accept her avatar as being the heroine. The story brings up the issue of what we should do with our physical bodies as we spend more and more of our time in the future inhabiting avatars in both virtual and real reality.

This then is where we are headed: a future that integrates real spaces with virtual and augmented realities, and a world in which I can effortlessly transfer my consciousness and experiences to an avatar that represents me. This will ultimately be so realistic that I will find myself reminding my friends and colleagues that I am an avatar.