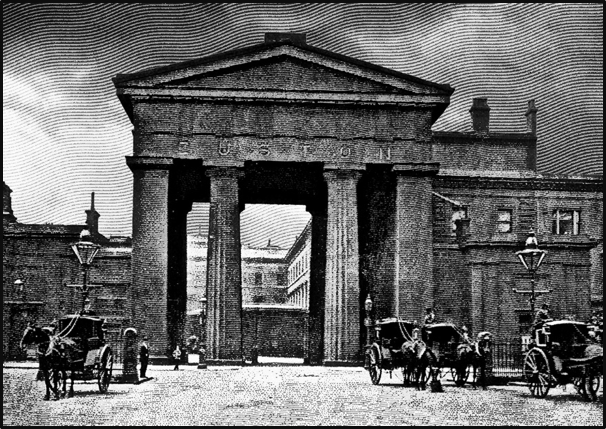

mail sack was unhooked from its pole and flung into the postal car of the Royal Scot as it rattled, at fifty miles an hour, toward Glasgow. McGloury had been late to meet Mother at Euston Station.

mail sack was unhooked from its pole and flung into the postal car of the Royal Scot as it rattled, at fifty miles an hour, toward Glasgow. McGloury had been late to meet Mother at Euston Station.Chapter Ten

The Royal Scot & the Ferry to Millport Island

mail sack was unhooked from its pole and flung into the postal car of the Royal Scot as it rattled, at fifty miles an hour, toward Glasgow. McGloury had been late to meet Mother at Euston Station.

mail sack was unhooked from its pole and flung into the postal car of the Royal Scot as it rattled, at fifty miles an hour, toward Glasgow. McGloury had been late to meet Mother at Euston Station.

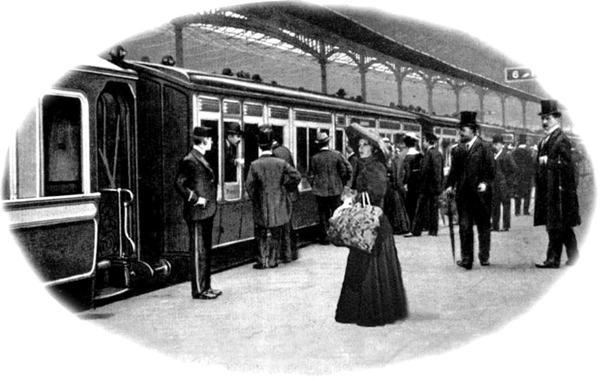

He dashed through the great hall, his single travel bag gripped tightly in one hand while vigourously waving his walking stick in the other. He reached the platform and, tossing his bag ahead of him, jumped into the compartment as the train was starting to move, precisely at ten (the London and North Western Railway waited for no man who did not have a weighty title). The train pulled away. McGloury, quite out of breath, nodded to Mother. Out the window, before too much time had passed, the city of London gave way to the greener home counties.

McGloury, new to farming, had been explaining to Mother, in excruciating detail, the tribulations of crofting, raising sheep, weather, and his recently acquired expertise on the uses of fertilizer. Normally Mother was keen on acquiring knowledge on a plethora of subjects. She maintained that you never knew when mastery of an odd fact might come in use. But after three quarters of an hour, she felt that the subject had been more than exhausted. Tasha was about to reveal that her interest in manure was limited, when McGloury noted the scenery that flashed by out the compartment window. “That’s a bonny bit of country out there.”

Speeding by were neatly laid out farms, with orderly stone walls set amid a landscape of fertile green. It appeared so safe and serene.

“’Tis a wee garden compared to Scotland,” continued McGloury, as he rhapsodized about his native land. “And green, you dinnae know green ’til you stand on the banks of Loch Lomand with the highlands beckoning in the mist.” Then he gave a sigh and admitted, “But I must admit that, aye, these English farms have a simple charm.”

“They do indeed, Mr. McGloury.”

He gave a short laugh. “Now, you’re not saying that a fine lady like yourself would bide awhile tramping the fields or clambering over cattle fences?”

“It might surprise you to know that I spent a summer’s week on a farm just two stops up this very line.”

“Were you on holiday, then? Pretending to be a country mouse?” he asked with a laugh.

Mother sighed with pleasure as the memory came back to her. “It was invigorating. The corpse of the owner’s father-in-law was strewn about six different points of the stable. Just finding all the pieces presented a challenge. Still, I was able to clear the poor farmer. Though I am certain there are nights when he wishes his wife was at his side, rather than in Pentonville prison, despite her facility with an axe.”

McGloury gaped at Mother for a moment, and then asked her to hand him the newspaper sitting on the edge of the seat. He made a point of being immersed in an article, his desire for conversation suddenly satiated.

“I think I’ll indulge in a nap,” said Tasha. “You don’t mind, I trust?”

“Not a wee bit!” he replied.

Mother closed her eyes. They had a long trip ahead.

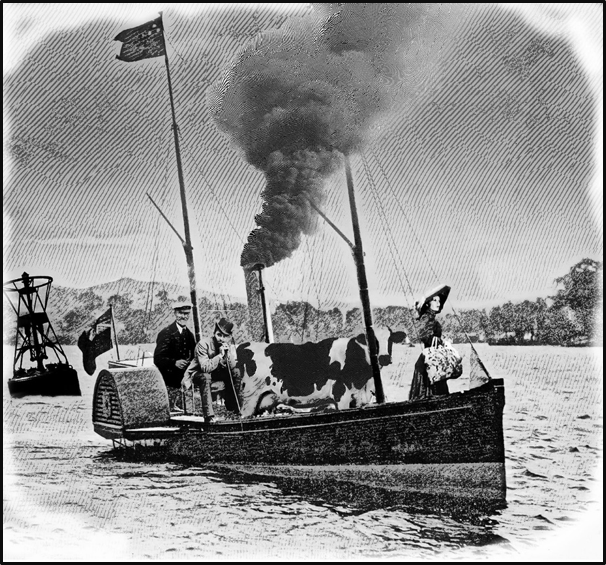

Although Glasgow was a modern city, and the Clydebank was one of the great ship building centres of the world, the only transportation to Millport Island was a single little ferry, scarcely more than a lifeboat with a steam engine, that left from the mainland town of Largs. Eventually, it would retire to the Glasgow Transport Museum, but in 1906 it still plied endlessly between Millport Island and the mainland.

The boat lurched in a heavy swell and spray inundated Tasha and McGloury, the only two passengers (save for a cow mooing in discomfort toward the bow). The ferry captain, a type referred to at the time as a “grizzled old salt” or when being affectionate, “Jolly Jack Tar,” took a tarp from a chest in the stern, strode past his human fares and covered the cow.

Tasha raised her voice, overcoming the engine and the water. “Is this the only transportation to the island?”

McGloury nodded stoically, and they both huddled from the spray.

Tasha contemplated the dark water below with satisfaction. She loved swimming, and not just because of the exercise, but for the way that water—even when near frigid—engulfed her and simultaneously buoyed her up. She shifted her attention toward the bow of the boat.

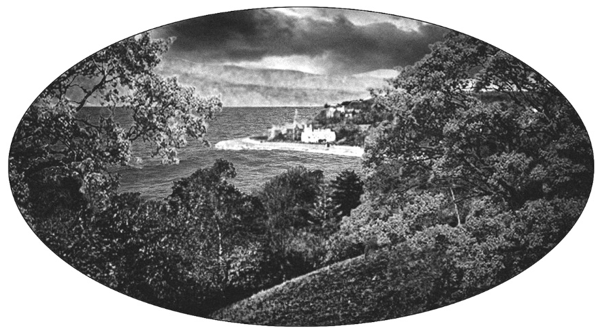

Ahead was Millport Island, with its little town and crofts scarcely touched by modernity. Earlier that day she had seen, as if in contrast, the towering hull of the new Cunard liner, Lusitania, at the John Brown & Company shipyard on the Clydebank. The ship was almost ready for launching. She would be the most modern and fastest ocean liner yet built. It was indicative of the turbulent era that the government had helped finance the Lusitania, and her sister ship the Mauretania, on the condition that in time of war, they could be used as auxiliary cruisers. Even in peacetime, the public would get something for the expenditure of money, for these swift ships were expected to keep the Blue Riband, the accolade for the fastest Atlantic crossing, firmly a British possession (there would be no physical trophy until 1935). Tasha mused that while she would spend the night only a few miles from this triumph of advanced technology, her abode would have no electricity, gas, or plumbing.