What is Entertainment?

Why do people read for recreation instead of doing something else? Why not go skiing, watch a movie, play chess, or hang out on Hollywood Boulevard?

Why do We Crave Stories?

I’ve never seen a definition that encompasses all types of entertainment, and there are many forms—sports, listening to music, attending parties, watching movies. When I was a prison guard, I knew killers who killed for pleasure, women who tried to seduce men for enjoyment. What do these have in common with fiction?

We have to answer that question before we can move on.

Years ago when I first began asking myself why people read, I really felt that the answers didn’t mesh.

Professors in college said that we read for escape, or because we enjoy the beautiful sounds of words, or for insights.

Fine, I thought, but I can escape by getting out of the house. If I want beautiful sounds, I’ll listen to Dan Fogelberg. If I’m looking to understand the world, I might be better off reading the encyclopedia or a newspaper.

Why do People Crave Stories, Good Stories, Written Down?

One clue came to me almost by accident. I happened to meet a professor who was talking to a friend. The professor was one of my favorite writing instructors, a woman who vehemently forbade her students from writing trashy genre fiction—romance, science fiction, fantasy, horror, westerns or anything of that ilk. She discouraged her students from even reading it, fearing that it would subvert their higher impulses as artists.

So imagine my astonishment when I heard her discussing with another professor how she had wept the previous night after reading a trashy romance novel. I was flabbergasted to discover this … this deceit. Why, she was nothing but a hypocrite!

So I confronted her, asking why she would even bother to read a romance novel. She explained that she read romance to relax. When life got stressful, her job got hectic, it was a good way to unwind.

Indeed, once I began asking others why they read, the words “stressful” and “relaxing” began to crop up more and more.

But on the face of it, that answer seemed absurd! When we read, we take part in a common dream. We vicariously experience what is happening. People go through tremendous difficulties in a novel. People get run over by cars or stalked by serial killers. People get raped, beaten, sold as slaves and struggle through constant turmoil. And it isn’t happening to others—it’s happening to us, as readers.

Books aren’t relaxing at all, are they?

And that’s when I saw a possible answer.

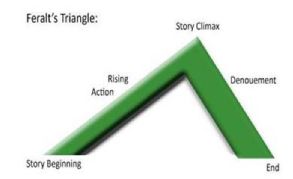

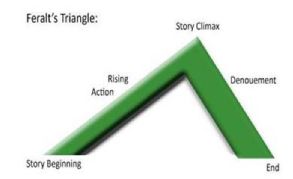

In an early writing class, one instructor talked about Feralt’s triangle. Feralt was French writer who studied what made successful stories. He said that in a successful story, the tale begins with a character that has a problem. As we read, the suspense rises, the problems become more complex and have more far-reaching consequences, until we reach the climax of the story, where the hero’s fortune changes. Afterward, the problem is resolved, the tension diminishes, and the reader is allowed to return to a relaxed state.

He put it on paper like this:

His vision wasn’t new or astonishing. After all, his work was based on the writings of Aristotle. (Note that most experts credit Freytag with developing the plot triangle. My teacher wasn’t one of them.)

But shortly after my experience with my closet romance-reading professor, I came upon an article in a medical journal and suddenly found myself looking at a chart remarkably similar to the plot triangle. The confluence of the three ideas helped me strike to the core of just exactly why people read for recreation.

The article explained some recent experiments on endorphins—internally created opiates that our body uses to help control pain. You see, as we live through our daily lives, we constantly are faced with minor pains. Cells age and die, we get minor cuts and abrasions, and to fight the pain that comes with these cellular deaths, our body creates a certain low level of endorphins. In essence, our body is constantly drugging us. If not, we would literally feel ourselves dying, wasting away, from moment to moment.

However, when you get injured—when you get cut or stick your hand in a vat of acid—cells die on a massive level and your brain suddenly registers the pain. This of course serves as a warning to get away from the source of pain—the vat of acid, the scalding hot chocolate, or whatever. But the brain also begins creating more endorphins in an effort to diminish the pain.

Eventually, the level of opiates produced by the body matches the level of damage involved, and then the pain you experience diminishes or vanishes completely. Depending on the severity of your injury, the process can take hours or days. A small cut may stop hurting in hours; a severe burn might not quit aching for weeks.

This is all a very common process in the body. It’s called a “biofeedback loop,” and the body uses it in thousands of ways. For example, as your body recognizes sugar in the bloodstream, it signals to the pancreas to begin secreting insulin so that you can metabolize the sugar. When the amount of sugar in your blood drops, the pancreas is then allowed to stop producing insulin.

In another example, as your brain recognizes a lack of oxygen in your bloodstream, it sends an impulse to your lungs to breathe more deeply. Once the bloodstream is oxygenated, your lungs are allowed to go back to rest.

Our body works based upon thousands of different kinds of biofeedback loops.

The interesting thing about endorphin levels to me was this: everyone has a resting level of endorphins in their bloodstream, and based on this level, we each have our own threshold of pain. Thus, if you jab me with a pin to a certain depth, I will recognize pain at a very consistent level.

But what happens when I get injured, say severely cut, and my body raises the level of endorphins?

The answer is: I will feel less background pain. The pinprick that hurt me a day before may go unnoticed the next, simply because I am naturally sedated.

This is why runners, people who walk barefoot, or people who subject themselves to rigorous and painful exercises have a much higher tolerance for pain than those who do not.

As I say, biofeedback loops are everywhere in the body, and I studied them often back when I was in pre-med.

But what fascinated me about this chart was how similar it looked to the plot triangle, and how similar the idea of coping with stress was with the concept of coping with pain.

Think of it, the body has to have some way to cope with stress. Otherwise, we’d get more and more stressed out until we all went nuts.

At that point I recognized that reading a formed story that conforms to Feralt’s plotting outline might be a type of emotional exercise that allows us to handle stress.

Obviously, each of us has background stress in our lives. Your stress may come from problems in your marriage, or fear that you’ll lose your job. It may have to do with concerns for your health, or the health of a friend. It may have to do with deadlines or other time pressures. Right now, without thinking much, you can probably come up with a dozen stress-inducing problems that you have to deal with today.

To cope with life’s little problems, we have three options:

—We may remove the source of stress completely. If you’re out of money, you can make a lot more, until you’re no longer stressed. If you’re sick, you can get cured. But removing the source of your stress isn’t always attainable. Sometimes you have to try something else.

—We may escape from stress by taking a vacation perhaps, or a night on the town. This is a temporary attempt to resolve the stress, but it doesn’t always help. Have you ever spent a vacation where you just agonized about what you needed to do at work? We can’t spend our lives at Disneyland.

—We can perform emotional exercise to help cope with the stress. In this scenario, you’re like a weightlifter, doing your reps in order to strengthen yourself. This is what happens when we entertain ourselves with reading, watching movies, watching sports, go skydiving, or try to “entertain” ourselves in any of hundreds of other ways.

The fascinating thing about a story is that it lets you escape from your stress and exercise simultaneously. By reading a book or watching a movie, to a degree you escape from your own life, your own world, and become immersed in a fictive universe. You take an emotional vacation from your own world. Typically this is most true in the opening of a story, where the author spends a good deal of time establishing the setting and the conflicts may be less significant and may appear more easily resolvable than at the end.

But if a tale merely distracts you, if it relates dull incidents about characters that never face significant trials, in the end you will feel cheated. You may say, “That story was good, but it would have been better if …”

Merely distracting a reader isn’t satisfying enough. If it were, people would read travelogues instead of stories.

No, in order for a story to be really satisfying, it must also be rejuvenating. When you read you must enter a world where you are placed in meaningful conflict, conflicts that build and deepen and grow. In other words, we exercise by dealing with imaginary conflicts.

In short, as many other authors have noted, the situations that are intolerable to you in real life are those that you crave in fiction.

For example, only a madman would want to leave his home, his family, and his friends, get stalked by the nine Black Riders, take a sword blade to the chest, battle orcs in the mines of Moria, nearly starve to death on the road, and confront Sauron in Mordor.

All of those things would be intolerable in real life.

But we crave them in fiction. Here’s why: Your subconscious mind does not completely recognize the difference between your real experiences and those that occur only in the imagination. So, when you become Frodo Baggins walking the road to the Crack of Doom, chased by Black Riders, the subconscious mind responds to some degree as if it were really happening. When you are Robin Hood, grieving for your dead father, your mind reacts as if it were really happening to you.

Indeed, the more completely you become immersed in a fictive tale, the more totally your body will respond.

How often have you found yourself reading a book with your heart hammering so badly that you had to stop? How often have you found sweat on your brow and your breathing shallow? So the body responds. It says, “I thought life was bad at the office, but this stress is killing me! Let’s handle it.”

In short, as your body gets stressed it releases chemicals to help you cope with the stress. Adrenaline and cortisol make your heart pound, your senses sharpen, and force your body to begin to store energy as fat.

At that point, some biofeedback mechanism kicks in. Your body, in an effort to handle the imaginary stress, seeks some way to cope.

As you seek for answers to the problems, your body releases dopamine in small amounts, exactly the way that a dog gets dopamine as a reward for sniffing at the trail of a rabbit. In short, you get little bursts of satisfaction, even as the conflicts deepen.

When your reach the climax to the novel, when you’re standing at the Crack of Doom, you reach the most important of your emotional exercise. Your heart may be pounding furiously, and in desperation you search for a release from stress.

When the stress is resolved and the obstacles overcome, just as the cortisol and adrenaline stop pumping, your body gives you another reward: it floods your bloodstream with serotonin, and when that happens, I suspect that the biofeedback loop is completed. Instead of suffering stress, your brains says, “Great job, you solved the problem. Here’s a surfeit of serotonin as your reward,” and you begin to bask in happy, fuzzy enjoyment.

You sit back in your chair and sigh, and say, “Wow, what a relief! I feel so much better!”

And the truth is you do feel better.

You’ve just performed an emotional exercise, very similar to a physical exercise. Reading is to the mind as aerobics is to the heart and lungs. Because you have performed this emotional exercise, you will be better able to handle the little stresses in your day-to-day life. The minor problems at the office seem to diminish in intensity and even the major catastrophes aren’t so intimidating.

In short, all forms of recreation boil down to this: recreation is any activity that helps us cope with stress by putting ourselves at risk in some controlled way so as to artificially raise stress for a short period of time

Let me show you how reading relates to most other forms of recreation: in some forms of entertainment, we may put our very lives in jeopardy—such as when we are skydiving, mountain climbing, bungee jumping, auto racing, and so on. But in order for us as participants to be rejuvenated by an experience, we must be able to control the element of danger. For example, jumping from an airplane without a parachute is suicide. But jumping from an airplane with a parachute is recreation. For me, racing a car at 600 mph would be suicide, but I’d feel fairly comfortable driving 140 mph, because I would be able to control the vehicle. I once heard a cowboy say that he “liked a little target practice from time to time, but that didn’t mean that he wanted to engage in a shootout every time he went to the bank.”

The sense of being in control of the danger is vital to the value of the exercise in rejuvenation.

When we play a game of skill—such as chess or golf—we don’t put ourselves in physical danger, but we do put our own status on the line. We put our place in society, our reputation, in jeopardy. This is particularly true in upper-level tournament sports. So when we play sports, we still have the elements of placing ourselves in jeopardy in a controlled environment.

If there is no jeopardy, the sport is unrewarding. For example, playing golf with a six-year old would be a bore. I could probably crush most six year olds. But playing Tiger Woods would be just as unrewarding—I don’t have the skills to even try. But trying to beat my best friend—and thereby either slightly raising or lowering my status in his eyes—could be entertaining.

In many sports we don’t risk our health or reputation—instead we may risk our wealth. Poker, dog racing, and many other games are valuable as recreation simply because we invest money into them. In short, we place ourselves in economic jeopardy. The more money we risk, the bigger the thrill. If we bet too much, the threat becomes unbearable. If we bet too little, it’s not really interesting.

Do you see the relationship between reading and other forms of recreation? Here it is: when we read, we buy into a shared dream, a shared fiction, and by doing so we put ourselves in emotional jeopardy.

To some degree, we thrust ourselves into the hands of a storyteller, trusting that he will deliver us safely from a daydream that swiftly turns into a nightmare. But we don’t want to trust him too much.

If the emotional jeopardy is too small, we get bored.

If the emotional jeopardy is too great, we’ll close the book.

If the author abuses our trust—if for example he doesn’t end the story, but leaves us instead in greater emotional jeopardy, or if the ending is too ambiguous, we will no longer trust the author and we’ll shun his fiction.

This same need for a happy outcome is true in other forms of recreation. Have you ever noticed that when your team is winning regularly, the stands at the football or basketball stadium rapidly fill up? We don’t want to invest emotional energy in a team that will let us down. We don’t want to watch games that our team can’t win. We won’t gamble on the lottery if no one ever hits the jackpot.

So here is the secret that I couldn’t learn in college: reading for recreation generally works best only as we read well-formed stories—tales where there is an ascending level of stress, doubt as to the outcome, followed by a conclusion where the stress is relieved.

In short, those “trashy” genre stories that my writing teachers didn’t want me to read—the romances, fantasy, westerns, and so on—sell well precisely because the audience does know within certain parameters how the story will end.

At the very heart of it, reading stories or viewing them allows us to perform an emotional exercise. And the better you as a writer are at creating fiction that meets your audience’s deepest needs, the better your work will sell.

In later chapters I talk about what a story is—a setup, expanding try/fail cycles, a climax and resolution. But form follows function. Just as we create chairs—whether they be stools, thrones, or lazy-boy recliners—to fit some basic human needs, a stories are also shaped to fit human needs.

Now, many types of writing aren’t stories. You can write anecdotes, interesting accounts of things that have happened to people. You can write essays to convince me of your philosophies. You can write a slice of life, or tell me a joke. But each of those types of writing is as different in form as an elephant is from a duck.

So, when we as professional genre writers talk about what a story is, we are talking about the form that has been discovered through trial and error by writers over the centuries.

This understanding of what a story is, and why and how it functions, leads me to conclude that there are a few basic principles to writing a formed story, as discussed below:

—A Writer’s Job is to Guide the Reader through a Stress Exercise. As an author I write fiction because I recognize that I am performing a service to my readers. They are looking for an emotional exercise, and it is my job to deliver. If I write unformed fiction—stories that have no ends, stories that are ambiguous in the end, or stories that have displeasing ends—I’m not fulfilling the trust that readers place in me. I’m not doing the job that they’re paying me for. In such a case, I will rightfully lose my readership.

—All Stories Must Create a Balance of Stress. If I do not create enough stress in my story, the story will bore the reader. If I create too much stress, the story will become unbearable and the reader will put it down. My job is to create a pleasing level of stress that rises toward a dramatic climax, then resolves.

—Not All Readers Will Be Pleased by the Same Story. Different readers require different levels of stress. Some people crave horror, just as some crave the adrenaline rush of sky diving. I don’t like either activity. At the same time, things that would bore me—say the story of a boy who wonders if he’ll ever get his first car—may be perfectly suited to a person who craves a less-rigorous emotional exercise. Thus, I will never write a story that will perfectly please all readers.

—Stress Levels Need to be Carefully Controlled Throughout the Story. In order to hold my reader, I must create some stress. At the same time, in order to make the story feel safe enough so that my reader gets emotionally involved, I have to make that stress level “safe.” I can do this in one of several ways. Typically, I make the conflict feel safer by transporting my reader into another time, place, or persona, but I can also relieve stress by offering hope to my readers that the stress will be resolved.

—I Must De-stress My Reader Properly. This typically means that I will resolve all of the important conflicts created in the story, usually in the most powerful way possible. My characters need to be more than relieved, they need to be almost giddy. Most of the time, I need to release my reader into a setting that is serene and at rest.

***