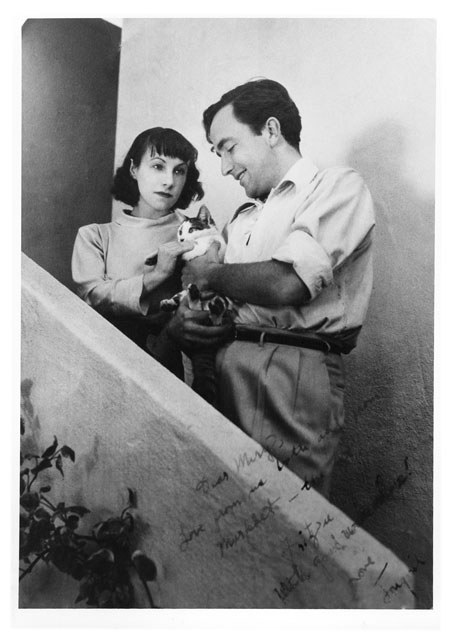

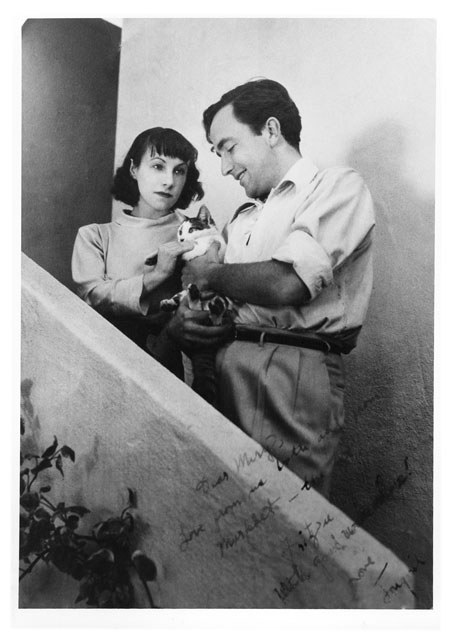

Fritz Leiber with wife Jonquil, Beverly Hills, 1937

Fritz Leiber with wife Jonquil, Beverly Hills, 1937

I met Fritz Leiber (it's pronounced Lie-ber, and not, as I had mispronounced it all my life until I met him, Lee-ber) shortly before his death. This was twenty years ago. We were sitting next to each other at a banquet at the World Fantasy Convention. He seemed so old: a tall, serious, distinguished man with white hair, who reminded me of a thinner, better looking Boris Karloff. He said nothing, during the dinner, not that I can remember. Our mutual friend Harlan Ellison had sent him a copy of Sandman #18, "A Dream of 1000 Cats," which was my own small tribute to Leiber's cat stories, and I told him he had been an inspiration, and he said something more or less inaudible in return, and I was happy. We rarely get to thank those who shaped us.

My first Leiber short story: I was nine. The story, "The Winter Flies," was in Judith Merril's huge anthology SF12. It was the most important book I read when I was nine, with the possible exception of Michael Moorcock's Stormbringer, for it was the place I discovered a host of authors who would become important to me, and dozens of stories I would read so often that I could have recited them: Chip Delany's "The Star Pit" and R. A. Lafferty's "Primary Education of the Camiroi" and "Narrow Valley" and William Burroughs' "They Do Not Always Remember," J. G. Ballard's "The Cloud-sculptors of Coral D" not to mention Tuli Kupferberg's poems, Carol Emshwiller and Sonya Dorman and Kit Reed and the rest. It did not matter that I was much too young for the stories: I knew that they were beyond me, and was not even slightly troubled by this. The stories made sense to me, a sense that was beyond what they literally meant. It was in SF12 I encountered concepts and people that did not exist in the children's books I was familiar with, and this delighted me.

What did I make of the "The Winter Flies" then? The last time I read it I saw it as semi-autobiographical fiction, about a man who philanders and drinks when he is on the road, whose marriage is breaking down, and who interrupts a masturbatory reverie to talk a child having a panic attack back to reality, an action that, for a moment, brings a family, fragmenting in alcohol and lack of communication, together. When I read it as a nine-year-old it was about a man beset by demons, talking his son, lost among the stars, home again. And both ways of reading it were, I suspect, as right as they could be.

I knew I liked Fritz Leiber from that story on. He was someone I read. When I was eleven I bought Conjure Wife, and learned that all women were witches, and found out what a hand of glory was (and yes, there is sexism and misogyny in the book and in the concept, but there is, if you are a twelve-year-old boy trying to make sense of something that might as well be an alien species, also the kind of paranoid "what-if-it's-true?" that makes reading books such a dangerous occupation at any age). I read a 1972 issue of Wonder Woman written by Samuel R. Delany, featuring Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser and was disappointed that it felt nothing like a Chip Delany story, but had now encountered our two adventurers, and, from the magic of comics, knew what they looked like. I read Sword of Sorcery, the Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser comics that DC comics brought out in 1973, and finally found a copy of The Swords of Lankhmar at the age of thirteen, in the cupboard at the back of Mr. Wright's English class, its cover (I would later discover) a bad English copy of the Jeff Jones painting on the cover of the US edition; and I read it, learned what the tall barbarian and the little thief were like in Leiber's glittering, half-amused prose, and I loved it, and I was content.

I couldn't enjoy Conan the Barbarian after that. Not really. I missed the wit.

Shortly after I found a copy of The Big Time, Leiber's novel of the Change War, a war across time and space being fought by two incomprehensible groups of antagonists who use human beings as pawns, and I read it, convinced it was a stage-play cunningly disguised as a novella, and when I reread it twenty years on I enjoyed it almost as much (aspects of how Leiber treated the narrator bothered me) and was still just as convinced it was a stage-play. Some of Leiber's better SF tales were Change War stories.

Leiber wrote some great books, and he wrote some stinkers: the majority of his SF novels in particular feel dated and throwaway. He wrote some great short stories in SF and fantasy and horror and there's scarcely a stinker among them, even when the SF elements feel tacked on or redundant or protective colouration for the fantastic.

He was one of the giants of genre literature and it is hard to imagine the world of tales we read today being the same without him. And he was a giant partly because he vaulted over genre restrictions, sidled around them, took them in his stride. He created—in the sense that it barely existed before he wrote it—witty and intelligent sword and sorcery; he was the person who put down the foundations of what would become urban horror; and he wrote SF that resonated in its time for its readers, and some that did more than that.

Leiber at his best has themes that repeat, like an artist returning to his favourite subjects—Shakespeare and watches and cats, marriage and women and ghosts, the power of cities and booze and the stage, dealing with the Devil, Germany, mortality, never repeating, usually both smarter and deeper than it needed to be to sell, written with elegance and poetry and wit.

Good malt whisky tastes of one thing; a great malt whisky tastes of many things. It plays a chromatic scale of flavour in your mouth, leaving you with an odd sequence of aftertastes, and when finally the liquid has gone from your tongue you can still find yourself reminded of, first, honey then woodsmoke, and bitter chocolate or of the barren salt pastures at the edge of the sea. Fritz Leiber's better short stories do the thing a fine whisky does, but they leave aftertastes in memory, an emotional residue and resonance that remains long after the final page has been turned. Just as the stage manager he describes in "Four Ghosts in Hamlet," we feel that Leiber had spent a lifetime observing, and he was adept at turning the straw of memory into the bricks of imagination and of story. He demanded a great deal of his readers—you need to pay attention, you need to care—and he gave a great deal in return, for those of us that did.

Twentieth-century genre SF produced some recognised giants—Ray Bradbury being the obvious example—but it also produced a handful of people who never gained the recognition that should have been their due. They were caviar (but then, so was Bradbury, and he was rapidly taken out of SF and seen as a national treasure). They might have been giants, but nobody noticed them; they were too odd, too misshapen, too smart. Avram Davidson was one. R. A. Lafferty another. Fritz Leiber was never quite one of the overlooked ones, not in that way: he won many awards; he was widely and rightly seen as one of our great writers. But he was still caviar. He never crossed over into the popular consciousness: he was too baroque, perhaps; too intelligent. He is not on the roadmap that we draw that takes us from Stephen King and Ramsey Campbell back to H. P. Lovecraft in one direction, from every game of Dungeons and Dragons with a thief in it back to Robert E. Howard, in another.

He should be.

I hope this book reminds his admirers of why they love his work; but more than that, I trust it will find him new readers, and that the new readers will, in turn, find an author they can trust (as much as ever you can trust an author) and to love.

Neil Gaiman

In Transit

February 2010