Jack Jones made his way into the sleepy little town of Elstow, about a mile south of Bedford in Bedfordshire, home to perhaps five hundred souls—give or take half a hundred. There was a notable stone cross in the center of town where he stopped to survey for a tinker's shop. "A bloody tinker!" he muttered. "I'm carrying mail for a tinker? What next, a milk maid? A bar wench? At least he's one of the better sort with a forge and a settled station." In a bit, when it was not obvious where he should go, he headed to the parish house next to the church of Saints Mary and Helen and approached to knock on the door. By chance the vicar himself answered.

Jack asked, in a slow voice, watching his word choice carefully to be better understood, knowing that his accent was often something of a bother, "Good marrow, good sir. Could you be directing me to the shop of one Thomas the son of Thomas, a tinker?"

"And you are?" the vicar asked.

"Jack Jones, dispatch rider, at your service. I'm up from London with a letter for Goodman Thomas, the tinker."

"A letter you say?" The vicar looked skeptical. "And just whom in London would be writing a letter to Thomas?"

"It was given me by the office of one Isaac Abrabanel just east of Temple Bar."

"Don't tell me Thomas has gone and borrowed money from a London Jew that he can't pay back?" The vicar let out a deep sigh. "That man will end in debtor's prison and his wife will be asking for charity. I knew it. I told her father not to let Margaret marry beneath herself. This is what comes of marrying for love."

"I wouldn't know anything about that, Vicar. I just have a letter to be delivered. Could you please tell me where I can find him?"

"Go to the cross. Face east. Take the middle of the three streets. When it forks, go left and the shop will be on your right. There is a shingle of a mended pot hanging over the door." The vicar started to close the door.

"One more question, of your grace, please. Would you know if Thomas has his letters or do I need to take a reader with me?"

"No, he does not. But his wife, poor woman, does." And with that the vicar did indeed close the door.

Jack led his horse through the town. When he entered the front door of the tinker's shop he was promptly addressed.

"What can I do for you?"

"Are you Thomas the Tinker?"

"No. Thomas is my brother. We share the shop. What can we do for you?"

"Does Thomas have a son named John? The lad would be not yet seven years of age."

"That's right. What is this about?"

"Could I have a few words with his wife, Margaret?"

"You could . . . if I have a mind to call her from the kitchen, which I am not about to do until you tell me what this is all about!" By this time the tinker had put down his tools and stood up from the bench, quietly picking up the heaviest of his hammers.

Jack decided he'd better answer quickly. "I have a letter for your brother. I suppose it will be all right if I give it to his wife, seeing as Thomas hasn't his letters and she will have to be the one reading it, anyway."

"A letter, you say?"

Jack lifted the flap on the pouch over his shoulder and brought forth a folded parchment, sewn with a string, set with wax and sealed with a stamp.

"Maggie?" the tinker called out.

"Yes?" The answer came from the back of the house.

"Can you come out to the shop, please?"

Margaret pushed open the door that separated the shop from the living area. She was drying her hands on her apron as she did.

"This fellow says he has a letter for your husband."

"How very odd," she replied. "Are you sure?"

"The letter is for one Thomas, the son of Thomas, a tinker in Elstow, who has a son named John," Jack said.

"That would indeed be my Thomas. But why, in the name of all that is holy, would anyone be sending Thomas a letter?"

"Goodwife, could you tell me your father's family name?"

"What an odd thing to ask."

"True enough. I've never been instructed to asked the likes of it before but—" Jack put the letter back in the shoulder pouch and lifted a small bag of coins. He tossed it up and down in his hand, causing it to clink with the distinct sound of large silver coins. "I was told to ask and if I didn't get the right answer, the letter and the money are to go back to London."

The tinker promptly answered. "Bentley. The family name is Bentley."

Jack set the bag down and dug a stoppered inkwell out of his shoulder pouch along with a quill and a bit of paper. "Goodwife, would you please assure yourself that the seal on the coin bag is unbroken and then sign a receipt?"

"What is the money for? What is all this about?"

"Now, how would the likes of Jack Jones be knowing that?"

"Perhaps I had better read the letter before I sign anything."

Jack shrugged and handed her the missive.

As she read it, her lips moving silently as if in prayer, her face became increasingly contorted by puzzlement. The tinker's face held ever more curiosity until it erupted like a spit melon seed. "Well? What does it say?"

"The money is to pay Thomas' expenses to go to London to discuss a business matter with one Isaac Abrabanel. Thomas is to see him three doors east of Temple Bar."

"A London Jew? What business does Thomas have with the likes of that?"

"You would know better than I, as tight lipped as the two of you are about money matters."

"You and Rose don't need to be worrying about how much is on hand and what is coming in."

"No. We're just supposed to figure out how to feed the lot of us when there isn't anything left to buy food with."

"Times are hard, woman. Thomas and I are doing the best we can. If you are so all fired concerned, we could save the cost of sending John to get his lettering."

"For sure, and then he could go through his life at the mercy of who ever it is that is reading to him. If he doesn't go now, he'll not go later when he's old enough to be of some use."

Jack was growing more and more uncomfortable. These were family matters that should not be discussed in front of a stranger.

The tinker opened his mouth and shut it. Jack suspected that he wanted to say "it never hurt me any," as many men would have. But Jack could well imagine many disputes—had even had some himself—that would not have happened if people had written the agreement down to begin with. It was a common enough problem in life.

Jack cleared his throat, "Gentle folk, if you could, I need a signed receipt. Then I can be getting on my way."

"What can you tell us about this?" the tinker demanded.

"I'm naught but a dispatch rider. I just need you to sign the bloody paper."

"Well, I'm nothing but a tinker and I don't give a damn what you need. She isn't signing anything until you tell us all you know."

Jack reached for the money but the tinker was faster. He held the bag out of reach. "All I know is what I've told you already."

"Well, tell us about this Abrabanel man."

"I never set eyes on him. I talked to a clerk in the front room of a fancy office with a big brass handle on the front door and an even bigger glass window. Now, either sign the bloody paper or give me the money and the letter to take back to London!"

"Sign it," the tinker told his sister-in-law.

Later that day Thomas came back from making the rounds. He walked through the door and before he could put the new lot of pots to be mended down he was hit by a question. "Brother, what business do you have in London?"

"What are you talking about?"

"Why does a man in London, and a Jew at that, want to see you in his office at 'your earliest convenience'?"

"Have you lost your head?" Thomas asked. "You know I don't know any Jew in London or anywhere else."

"Margaret, bring that letter out here and read it to your husband."

"Letter? What letter?" Thomas was puzzled.

"The one that came from London today while you were out. The one that came with more money than we've had at one time in years. Enough for you to take a coach to London and dine in fancy inns along the way."

Margaret pushed open the door. The total puzzlement on her husband's face told her all she needed to know. He obviously didn't know one iota more about what was going on than she did. She held up the letter for him to see, then she began to read it aloud.

Thomas listened to the end without saying a word. "So all I've got to do for this money is go down to London and talk to this man?"

"I read you the letter, Thomas. You can ferret out the meaning as easily as I can."

"I know, but it doesn't make any sense. What does he want with me? They've got tinkers aplenty in London."

"Well, brother, I guess you'll just have to go down there and find out."

"You say there's enough money to take a coach?"

"Don't go getting any fancy ideas, brother of mine. There was enough. After I pay off what we owe the tin man—and pay for the next round up front to get the discount we never have been able to afford—then there's enough left to take care of you, there and back. As long as you start out with a cheese and a loaf and don't dally along the way."

Margaret met her husband at the door with a satchel holding a small cheese about the size of a good cabbage, and two loaves of bread about the same size. "The cheese should see you there and back. You can buy more bread before you leave London." Two loaves, two days walk, fresh enough, but there was no point in Thomas eating stale bread when it could be had for a fair price. She gave him a peck on the cheek.

"Margaret, please. What will the neighbors think?"

"Thomas, the day I can't send my husband off to London with a kiss because the neighbors are Puritans is the day we will move to Rome. I still think you should have hired a horse, or taken the coach."

"No. My brother is right. The money is better spent. I'd walk twice that for a lot less. Besides, I probably couldn't stay on a horse anyway, then it would run off and how would we ever pay for it? I've got my walking stick. I'll see you in five days."

"Thomas, when you get there call yourself a brasier instead of a tinker. It sounds better."

With these words of advice from his wife, Thomas set off for Temple Bar in London, wondering each step of the way what it was all about.

While munching the last of his bread in the last of the daylight Thomas found Temple Bar. He asked where he could find the office of Isaac Abrabanel, thinking to locate where he would go in the morning.

"It's right there. That's his shingle hanging over his door, just three down. The one that reads Isaac Abrabanel, Importer. Didn't you look, or can't you read?"

Thomas suspected that the fellow he asked couldn't read either, but wasn't about to admit that to some bumpkin just in from the country. To his surprise, the window spilled lamplight out onto the street. A glance through the glass made it clear that people were about.

"Well, the sooner begun, the sooner it's finished." Thomas pushed the door open and walked in.

The clerk summed up the man in front of him with a glance. "It's after hours. Come back tomorrow."

"Is this the office of Isaac Abrabanel?"

"Yes. We open at eight in the morning."

"He wants to see me."

"I'm sure he does! Tomorrow."

"Tell him Thomas Bunyan was here, then. I'll be back tomorrow."

"Thomas Bunyan? The tinker from Elstow?"

"I prefer to think of myself as a brasier."

As Thomas turned to leave, the clerk realized he had just made a big mistake. "Please, wait a moment, sir. Let me check with Mr. Abrabanel. I know he is anxious to speak with you."

The clerk came back in short order. On the one hand, he was vindicated. His boss would see the ragged scarecrow tomorrow. He was in a conference at the moment and it would run late. On the other hand, he was unhappy. Yes, he could lock up and leave, but he was to buy the dusty countryman a good dinner and settle him into a decent lodging. And he was to see the fellow back to the office in the morning. It wasn't the way he'd intended to spend his evening.

"Mister Abrabanel is tied up right now. He will see you in the morning. Join me for dinner and then—"

The tinker brushed at his shirt. "I've eaten."

"Are you sure? There is a very nice dining establishment just around the corner."

"I'm sure."

Avram, the clerk, was annoyed again. There went the paid for dinner he was looking forward to, even if it meant being seen with a tinker. "Well, then. Let me get you settled into your lodging for the night."

Thomas took one look at the hired room. It was, without question, the finest room he had ever even seen and he would be spending tonight here. There was a huge bed, a fireplace laid but unlit on an August night. The wash stand, sink and pitcher, along with an actual bath tub were absolute luxuries. "I can't afford this."

"Oh, but it's at our expense."

"You're sure?"

"Of course." The clerk hesitated a moment. "Dinner is at our expense also . . . if you would care to change your mind?"

Later, Thomas, smiling, stuffed and bathed, settled into bed with the knowledge that his laundered clothes would be returned in the morning. "A fellow could get used to this if he wasn't careful."

"Master Bunyan, it is good to meet you. Please be seated. How was the coach ride down from Elstow?"

"I walked."

"Oh, I see. Your wife and young John, they are in good health?"

"Yes."

"Well, Thomas . . . do you mind if I call you Thomas?"

"Most do."

"Yes, well . . . Thomas, I have been instructed to pay all of your expenses if you will relocate your family to the town of Grantville in the Germanies."

"Grantville?"

"You've heard of it, I'm sure."

"Yes. I've heard of the city from the future . . . and I've heard of the sea monsters that dwell in the lakes of Scotland. You might as well pay my way to the New World so I can move into one of the Spanish cities of gold and start making golden pots and kettles."

"I assure you, Grantville is real. I have a cousin there. He wrote me concerning you and your family. You are wanted in Grantville. All expenses are to be paid. A complete shop will be provided and there will be more than enough work—at a sufficient rate of pay to more than provide a good living for your family and a good education for your son."

"Why?"

"What?"

"Why? They have tinkers in Germany. Why does someone want me?"

"Well as you have heard, Grantville is from the future." Isaac held up a hand to forestall Thomas' objection. "I assure you it is true. So, while you may have lived a very ordinary life up till now, it would seem that you will do something extraordinary in the future and someone wants that to happen in Grantville."

"What?"

"I have no idea. Perhaps you will invent something or create some notable works. Perhaps it is young John who is to do something of note, or a child yet to be born? I wasn't informed and I don't know. What I do know is that you are wanted there and I am to see to it that you get there if you are willing to go."

Thomas' mind raced. The bag of coins in his brother's keeping, the room and the meal last night, the bath and the clean clothes, the fancy office. Someone was willing to spend money like Thomas had never had and never dreamed of having. Still . . . "There is a war in Germany."

"Yes, but not in Grantville. It will be quite safe, I assure you."

"This is beyond belief!"

"Yes, I imagine it is. But it is quite true. Master Bunyan . . . Thomas . . . there is a ship leaving in six days. I would like it very much if you and your family were to be on it."

Thomas sat in silence.

"You will want to discuss this with your wife." Isaac brought a small bag of coins out of his desk drawer. It had been prepared for just this point in the conversation. He let it drop several inches, in a spot Thomas could reach. It made the sound that only comes when gold meets gold. "Take a coach home. Think about the offer, and then bring your family back to London by coach. At least, let your wife sit in on the discussion." Isaac had laid the bait. Now it was time to set the hook. "I am authorized to tell you that money for a return trip will be on deposit with us until you use it or it is released to your heirs at the time of your death."

Secure in the belief that the Abrabanels would be successful, and looking to the patent and copyright laws

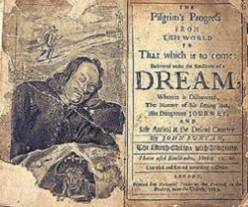

in the books he'd read, an attorney in an office in Grantville was quietly preparing a brief to claim the royalties for Pilgrim's Progress for young John Bunyan. True, John hadn't written it or any of his other works yet. But he was undeniably the author. It was a fine point. A very fine point of law. He would have to argue it in court, of course. But he thought he had quite a good case.

Elsewhere in Grantville, an old Free and Approved Mason was wondering what John Bunyan's output would be when he had received a first class education. The expense to find out was well worth it.