"Fire ready!" Sulun shouted warning.

"We're safe," and, "Go ahead!" came two muffled voices from the trenches behind him.

In the middle of the dirt courtyard, a careful arm's length from the metal tube posed on its wooden mount, Sulun hitched the hem of his tunic above his knobby knees and inched the glowing end of the lighted reed toward the waxed string fuse.

The flame caught, sputtering a bit, and the fuse began burning toward the hole. Sulun dropped the reed, turned, and ran for the trench. Omis's fire-scarred arms caught him as he tumbled in.

"Shhh!" snapped the burly soldier beside them. His studded leather armor creaked as he peered over the trench's edge. "It's burning, almost there . . ."

The other two stuck their noses out of the trench and watched as the sullen little flame worked its way up the fuse, across the base of the squat iron tube, and into the narrow hole.

Nothing happened.

A snickering came from the windows of the mud brick house that closed the courtyard behind them. The apprentices.

"Don't laugh yet," snapped Omis, looking over his shoulder. "I've seen fire play worse tricks—"

A roar came from the bombard. Smoke and flame belched from its raised mouth, and a rattling something whistled out too fast to see.

"'Ware low!" bayed the soldier, as he always did, as if this were an ordinary catapult.

"Going out to mid-river," Sulun noted, peering after the whizzing projectile as the crooked smoke trail arched out the ruined garden wall between two eight-story apartment buildings, and across the dike and moored rowboats.

"Kula, Mav and Deese of the Forge, let the seams hold!" Omis was praying.

The little gang of apprentices cheered and whistled from the house behind them. Neighbors on either side shouted and swore, heads came out of apartment windows, and the neighbor next door threw some garbage out his window. Out on the river a sudden waterspout rose, crested, and fell back.

"Within a yard of the buoy!" Zeren the soldier announced, standing up and starting to climb out of the trench.

"Not yet!" Sulun caught him by a booted foot. "We have to inspect the tube first."

Zeren waited, grumbling. Ordinary catapults weren't so temperamental; once fired, they were done. This iron bombarding tube of Sulun's seemed as fractious as a bored palace lady.

But oh, if she could be made to perform reliably . . .

Big Omis reached the bombard tube first. He inspected it anxiously, peering at the welds, poking at the touch hole, and patting the base of the tube to check its heat. "She seems to be holding," he shouted back. "I think that lard-flux weld is just what we needed."

"Will she fire again?" Zeren shouted, scrambling up from the trench at Sulun's heels.

"Should," Omis said.

Sulun, likewise patting the tube to check its heat, cautiously waved toward the house, toward youngsters clustered in the courtyard doorway.

His apprentices came tumbling out like puppies, toting the necessities in a proud little procession: tall, twenty-year-old Doshi hefting the stiff leather tube of round stones; Yanados with the measured bag of firepowder, swaggering enough to show the width of her woman's hips under the man's robe and cape; skinny little Arizun bearing the fuse and the reed and the tamping brush in his arms as if they were sacred symbols in a temple procession.

Omis chortled at the show, but Sulun scarcely looked up.

First he took the brush Arizun offered and worked it cautiously down the tube's barrel, feeling for obstructions. Next he took the new fuse and worked it carefully into the touch hole. Then he pulled out the brush and delicately poured the black firepowder into the tube, at which point everybody else took a respectful step back.

He reinserted the brush, tamped firmly twice, and withdrew it.

Last came the greased leather canister filled with stones. He struggled, lifting the heavy container so as to position it into the muzzle of the bombard tube. Failing to do that, he set it down and prepared to try again.

Omis stepped forward and shoved him grandly aside. "Here," Omis laughed. "That's another job for the blacksmith." Omis picked up the canister in one hand, hauled it up, and shoved it smoothly down the barrel.

"Still, better let me do the tamping," Sulun insisted, taking up the brush again and pulling the tattered ends of his flapping sleeves up to his elbows. "After all this time working with firepowder, I've learned a certain touch for it. . . . Ah, there!" He tamped carefully, withdrew the long brush, and checked the fuse. "Ready, test two!"

Everybody but Sulun ran for cover in the house or the trench.

"Now where's my tinderbox?" Sulun searched among the half-dozen pouches on his belt.

"Here." From the trench, Omis clambered out of his refuge with the little box in hand. "You dropped it when you fell on me."

"Oh. Um. Yes." Sulun scratched repeatedly at the box's scraper, lit the whole tinder compartment, then realized he didn't have the reed ready to hand. Inspired, he shoved the burning tinder at the end of the fuse. It caught.

Fast.

"Fire ready!" Sulun squeaked, scrambling for the trench. Once more he dived in headfirst, and once more the blacksmith caught him.

"You've left your tinderbox up there," Zeren commented, watching the fuse burn. "'Ware low!"

The back door of the house slammed. Yells. Arizun's voice protesting.

The bombard fired with another roaring belch of fire and smoke.

Again the canister whistled off toward the river, leaving a snaking trail of smoke between the buildings, and finally landed, sending up a geyser of muddy water and reed.

"It hit the marking buoy!" Zeren crowed, starting to his feet. Omis jerked him down.

Again the neighbors swore and yelled, "Noisy wizards!" Another load of garbage came flying out the window over the south wall, this one containing parts of a freshly slaughtered chicken.

Once more the engineer, the blacksmith, and the Emperor's soldier inched out of their safety trench and went to inspect the bombard.

"I don't know, I don't know," Omis fussed, brushing his curly black hair out of his eyes. "The seams look all right, but she's hotter this time, I think. . . ."

"Best wait till she cools a little then," said Sulun, fumbling around in the weeds after his dropped tinderbox. "Hmmm. Of course that could be a problem in actual combat. . . ."

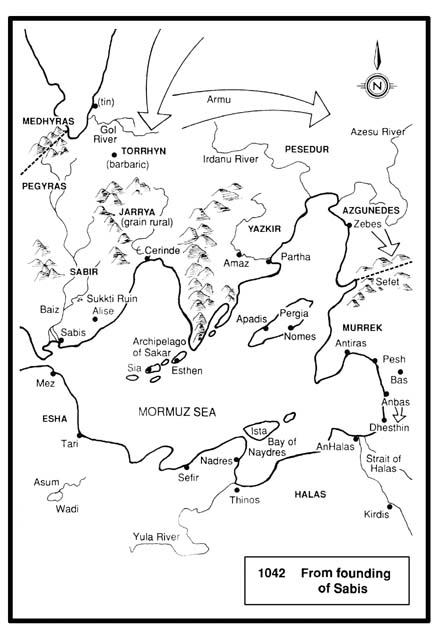

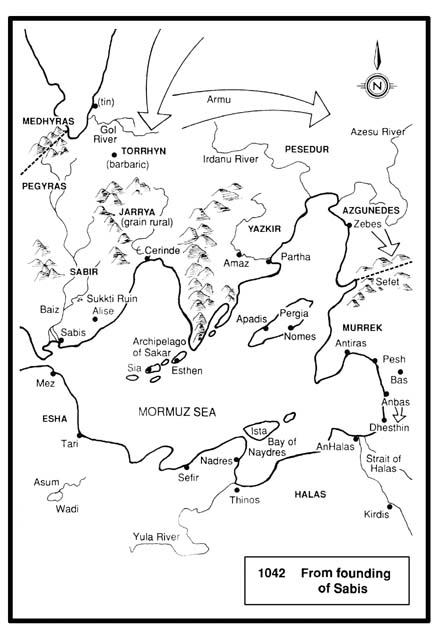

"No worse than reloading and rebending a catapult." Zeren waved the objection aside. "We'd have a whole battery of these things, half a dozen at least, the first would be cool again. Definitely faster than catapults, Sulun! And the distance! Given a dozen of these pretty bitches, we could retake the whole north country. . . ." His pale eyes, seeing a vision far beyond the muddy Baiz river, held a look of quiet, infinite longing.

"Don't count your conquests yet," Sulun said, waving for his apprentices and their gear. "We're still not sure this model can withstand repeated fire."

"Good ten-times-hammered iron!" Omis snapped, indignant. "And fluxed with lard in the mix, this time! Those welds could hold an Eshan elephant!"

"But it's not an elephant they have to hold," Sulun muttered, peering down his long nose into the barrel of the tube. "I suspect we're dealing with forces stronger than any beast that walks, any whale that swims or wind that blows—"

"Magic!" Arizun chirped at his elbow, handing him the tamping brush. "True sorcery!"

"Natural philosophy," Sulun corrected him, plying the brush. "Sorcery deals with spiritual forces. I deal only with material—Hoi, Omis! It's snagged on something!" He poked it again with the brush.

Omis took the tamp into his hands and tried it, then pulled it out "Obstruction," he said gloomily. "About halfway down the barrel. And I left my tools back at the big house."

"Let me." Zeren drew his sword in a quick, smooth motion, and poked its satiny grey length down the tube. "Ah, there. Soft . . . Just a second. Ah, there!" He pulled the sword out, held it up, and displayed the blackish lump stuck on the end. "What in the hells is this?"

Sulun rolled his sleeves up above his bony elbows and took a close look at the thing.

"Mmm, some sulfur? Perhaps not mixed smoothly in the grinding?"

He shot a look at his apprentices. Twelve-year-old Arizun looked indignantly innocent. Yanados shrugged and shook her head, denying responsibility. Doshi looked hangdog guilty, but that proved nothing: Doshi always looked guilty when anything went wrong, no matter whose fault it really was.

Sulun studied the mass again. "Huh, no . . . I think its a piece of charred leather from the canister. Ah, that would mean that the stones weren't contained. They spread in a wider pattern. No wonder the buoy went down!"

Omis, busy with the tamping brush, didn't notice. "It goes all the way down now," he announced. "Do we try again?"

"Yes." Sulun straightened up and reached for the bag of firepowder. "We've got to. The whole point is, we've got to be sure this design holds repeated firings."

"Better than the last one, anyway," Zeren muttered, shaking the lump off his sword as he headed for the safety trench. He called back, "That one peeled like an orange at the second blast!"

The apprentices fled. Omis took cover beside Zeren in the trench. This time Sulun took care to have the reed ready, lit it off the tinder, closed the tinderbox, and put it away before he lit the fuse. Once more he shouted warning and ran for the trench. Once more the door banged, everyone ducked, watched, and waited.

Nothing happened.

They waited longer.

Still nothing happened. Smothered chuckles from behind the wall and opened shutters above told that the neighbors were listening. A knot of local boys leaned out the windows of the left-hand apartment building, throwing out catcalls, jeers, and one or two empty jugs.

Still nothing.

"Hex," Zeren whispered. "Dammit, the neighbors—"

"Hex, hell. Hangfire," Sulun whispered. "It hasn't caught yet, that's all, it's just smouldering."

"Hex," Zeren said.

Possibility. If the neighbors got a pool together, they might afford someone potent enough.

Or if their master Shibari's fortunes were truly slipping . . .

Sulun ran his fingers through his wiry birds-nest of dark hair, bit his lip, then scrambled for the rim of the trench.

Omis grabbed him by the tail of his tunic. "Uh, I wouldn't go out there yet."

Sulun sank back again, unnerved. Hex or not, dealing with a smouldering waxed wick in the touch hole was not a comfortable situation.

And even a little hex could overbalance an already bad -situation.

With firepowder involved . . .

"Oh, piss on it!" Zeren picked up a stone from the bottom of the trench and threw it toward the iron tube, striking it neatly at the base.

The bombard tube exploded. With the loudest roar yet, the flames and smoke erupted from the mouth and center of the bombard, throwing stones, leather shreds, and splinters of hot iron skyward. Quick thunder echoed off the surrounding walls. Dark orange flame lit the ground and the weeds of the garden court, making new shadows where the sun should have painted light. Thick yellow-white smoke rolled outward, filling the yard with heavy, dry mist that made everyone cough.

The echoes faded, leaving a shocked silence. Even the river birds were struck dumb. Then shutters opened in the haze of sulfur reek and a ragged cheer went up from the neighbors, followed by applause, more catcalls, whistles, and laughter from the apartment buildings. The southside neighbor threw a whole cabbage over the wall.

Sulun and Omis climbed gloomily out of the trench and plodded over to study the damage. Zeren didn't bother to watch them. There was no bombard. There was no firepowder. Therefore there was no danger. The apprentices had figured it: the house door had opened. Zeren tromped toward it, collared Doshi, clapped some copper coins into his palm, and sent him off to fetch some wine at the tavern on the corner. Arizun, after a moments look at the disaster, scampered back into the house to get clean cups. Yanados, out in the yard, commented to anyone listening that the cabbage was big enough and clean enough to make part of a consolation supper.

The neighbors, seeing victory, slammed shutters against the stink of smoke and went to gossip.

The bombard tube was ripped open along one side and bent by the force of the explosion. Ragged shards of iron jutted from the gaping tear, and the wooden mount was splintered.

"May as well use this for firewood," Sulun noted, picking up the shattered mount.

"It was the seam," Omis said gloomily. "I've tried everything I can think of, or ever heard of, and nothing holds. Maybe it was a hex."

"Hex or firepowder, it'll still blow at the weakest point. It's always the weakest point. It can't have a weakest point. We'll fix it. We'll come up with a new design." Sulun gave the twisted metal a lack. "No point wasting all this good iron."

"How do I make a tube without a seam?" Omis grabbed and tugged his woolly hair, staring at the mess. "How? Out of solid iron?"

"Doshi's back with the wine," Zeren announced.

Sulun shouldered the firewood, Omis gathered up the ruined bombard—at least the major pieces—and they went inside.

"How do you make a tube without a seam?" Omis was asking for the fourth time, over his third cup of wine. In the dimmed afternoon light his bearded, spark-scarred face looked flushed and boyishly distressed, and he drew admiring looks from Yanados, across the table, that were much out of character with her apprentice boy's disguise. Sulun smothered a wry laugh behind his hand; Omis was not above twenty-five years of age, remarkably un-scarred for his trade, and certainly handsome enough under the frequent layer of soot.

Omis was also busily and happily married, another of Shibari's freedmen working mostly at Shibari's house. A shop uptown, a wife, couple of kids in the estate itself—Yanados didn't have a chance there.

Yanados, now . . .

Sulun turned the half-full cup in his hand and studied her over its rim.

In the four years since he'd left old Abanuz's tutelage and applied to Shibari as tutor, philosopher, and sometime (more frequently lately) naval engineer, he'd learned that Yanados's case wasn't unique; a young woman with no family, no dowry, and she had few choices in Sabis—or anywhere else for that matter: prostitution, slavery, thieving, begging . . .

Young men, however, could enter the various guilds as apprentices and work their way up to a respectable trade. And disguise, at least as regarded the public eye, was easy. Take off the clattering jewelry, flounced dresses, filmy veils, headdresses, face-paint; take away the willowy poses, fluttery gestures, and giggles. Put on the simple tunic, hooded cloak, plain sandals of a boy of the trades; lower one's voice, stride straight, bind the breasts if need be, swear a little—and behold, a young man.

How many males one passed on the streets, Sulun wondered, weren't? Who could tell? Who even knew to look?

A master would. A master might exact convenient bargains for keeping her little secret. So might other apprentices. But everyone in Sulun's workshop knew about Yanados, and Sulun took no such bargains, nor did anyone else—not even Zeren. Master Shibari had no idea. Neither did Shibari's other servants and freedmen and retainers—which, given Yanados's not uncomely lines beneath her man's garb, argued that a servant was a servant even to other servants. Odd notion! Sulun wondered if anyone in Sabis these days bothered to look beneath the superficial things, like dress, like manner, like social status.

"If we report another failure to master Shibari," Doshi mourned over a slab of bread and cheese, "he'll probably turn us all out. Reckoning how bad his finances are these days . . ."

"So we won't tell him," Arizun piped up, helping himself to another cup of barely watered wine. "What the nobles don't know won't hurt us."

Sulun grinned. Best of friends, total opposites, that pair. Tall, pale, rawboned Doshi was a farmer's son from the Jarrya grain belt, tinkerer, dreamer by nature, with frustrated hopes of becoming a scholar in the city. The Ancar invasions that had driven his family out of their farm and south to Sabis had likewise given him his chance of apprenticeship—but it had ruined the rest of his farmer kin, and that stroke of fate left Doshi permanently guilty of something, anything, everything around him so far as Doshi's thinking went, poor lad.

Now Arizun—small, dark, eternally cheerful Arizun—never felt an instant's remorse for anything that was his fault. Arizun had been working a street magician/fortune-telling racket in the Lesser Market when Sulun had first seen him—little scamp pretending to a wizard's talent, petty hexes for a few pennies—hexes the effectiveness of which nobody could prove yea or nay. A little sleight of hand, a lot of glibness, a clearly brilliant, and thanks to someone, even literate street urchin who plainly deserved better circumstances—as Arizun himself had pointed out. Sulun had offered him an apprenticeship, and Arizun had jumped at the offer: no relatives to notify, nothing to pack but the clothes he stood in, no regrets, and not a single glance backward.

So now the boy made an honest living, mixing firepowder and learning chemistry, making tools and learning mechanics, running errands and teasing poor Doshi for his gloom and his -bookishness—and Doshi seemed to enjoy the association thoroughly. Fair trade: Doshi helped Arizun with his reading and his math, and Arizun taught Doshi a hundred and one tricks of survival and success in the ways and byways of the city—many of them legal. With any luck, Sulun reckoned, they'd stick together, maybe set up a shop as a partnership when they finished their apprenticeship in Shibari's house.

"The best of weapons, if it doesn't come too late," Zeren was muttering to himself, leaning on Omis's shoulder. "If we'd had it twenty years ago, Azgunedes wouldn't have fallen. Of course I wouldn't be here. D'I ever tell you my family were educated folk?"

"Oh, yes," Omis sighed. "Many times."

"We owned two thousand hectares above the southernmost loop of the Azesu." The mercenary had that sad, faraway look in his pale eyes again. "A good villa—smithy, tannery, potter's shop, ever'thing. In a good year, we sent ten wagonloads down to the capital. In a bad year we never needed set foot off our own lands: we could make everything we wanted. There were tutors taught all the kids on the estate. A respectable library. Even the cook's boy could read." Zeren peered into his winecup. "D'I ever tell you, when I was a boy I wanted to be a philos'pher?"

"Natural philosophy?" Sulun pricked up his ears. "Is that why you hang around our little studio?"

Zeren shrugged, looked away, and reached for the salad bowl.

"Then why'd you become a soldier?" Doshi asked, all innocence, around a mouthful of bread.

Yanados glared, and must have kicked him. Sulun winced.

Zeren favored Doshi with a fast, angry glance, then looked away again, raking salad onto bread.

"Really, Doshi," Omis said.

"Really what?" Doshi asked, looking from side to side.

Sulun said, under his breath, "Everybody knows what happened to Azgunedes."

"Well, of course," Doshi said, rubbing his leg under the table. "The Armu horde—"

"Doshi," Sulun said.

"The Azesu river," Zeren said quietly, looking out the window. "We saw them coming—could see it from the villa wall, the dust they raised. They came wading across the ford half a day north of us, so many they made the river run mud. One day was all the warning we had. One day to pack everything we could carry, herd in all the cattle we could reach, and move everything down the road—right through the troops coming up from Zebes. And the army commandeered half the cattle, right there on the road. We got to the city with almost nothing, and the general ordered every able-bodied man we had pressed into the army—including me."

"I'm sorry," Doshi whispered, staring at the tabletop.

"Wasn't a bad life," Zeren said. "Oh, the food was terrible and the officers were worse, but at least I could strike back at the Armu. We had some hope we could throw them back, at least turn them, establish a new border—at first we thought that, anyway. I didn't see the fall of Zebes, never found out what happened to my family. It was just fighting and running, grabbing what supplies we could, fighting and running again, all the way into Murrek. Those of us who were left signed up with the Murrekan auxiliaries. . . ."

Yanados cleared her throat and offered a lighter tone, "Didn't know Murrek ever had the money for auxiliaries."

"Murrek didn't have shit." Zeren gave two syllables of a sour laugh and leaned back, easier. "Except for brains. Orders and officers changed every fortnight, and the royal house wasn't much better: assassinations, coups, intrigues under every table—total confusion. The wiser heads in Murrek packed up and ran for the south, even before the hordes took Sefet. I figured it was better to join them. South, all the way to Halas, where I joined the King's Own cavalry regiment." Zeren poured the last of the jug into his cup. "The things I saw, the stories I could tell you about Halas, about the whole south coast, in fact. I must have soldiered for every king and lordling clean across to Mez, right in front of the tide—and it just kept coming. Kingdom after kingdom. Never served in anything could hold it back—till I got to Sabis."

"Well, Sabis won't fold." Yanados tried to sound cheerful. "They've hit us before. We're still here. And you're doing all right second captain of the City Guard—"

"I'm not sure even Sabis can hold out." Zeren sighed, refusing now to be cheered. "Good gods, look around you. Who's on the throne? A nine-year-old child and his aging grandfather. Who rules the court? An army of courtiers and clerks and dotty wizards, the whole court worm-eaten with its own petty intrigues—"

"Zeren, be careful!" Arizun glanced significantly at the windows.

"So who bloody cares?" Zeren growled.

"Nobody but our neighbors," Doshi said.

"Gods know, they probably tell worse on us. Hell with the court. Taxes on everything. All of it to feed an army that's full of outland mercenaries like me! I make no claims for any great virtue, but most of them are far worse, and far stupider, than I am. Gods, I've seen them back stab each other for pennies, mutiny, duck out of fighting whenever they can, never stop to think this is the last, the last damn place that's got a chance to hold out! If the cities north of here fall, it goes; and their money won't buy them anything—not the court, not the mercs. Not after that."

"Ah . . . should I go out for more wine?" Arizun asked, neatly snagging the empty jug.

"Hell, yes!" Zeren threw him a silver coin. "Keep the change."

Arizun grabbed the coin and darted out the door.

Silence lingered.

"Well," Yanados said cheerfully, desperately. "Well, half an army's better than none. With the Armu busy tearing up the east, maybe it'll be barbarian against barbarian a while; maybe nobody else will push toward Sabis. Why attack the sheepdog in a field full of sheep?"

"Not just the Armu now." Zeren glowered at the dropping level in his winecup; took another drink. "The last few pushes—the ones that took north Jarrya—"

Doshi winced, and took a drink himself.

"—were from a new tribe, these damn Ancar you've been hearing about. Not Armu. Who, d'you think, pushed the Armu hordes south in the first place?"

"We always thought it was the drought," Doshi muttered. "Those bad years in the north, Grandpa always said—"

"Bad weather pushed the Ancar. The Ancar pushed the Armu. The battle of the Gor kicked the Armu eastward then, they came down on the south—but the Ancar still kept coming. They're two hundred leagues south of the Gor already, that's what the scouts say. That's what they're not telling out in the streets—yet. Ancar's hell and away a worse enemy than our grandfathers fought in the Armu wars, and Sabis's hell and away a lot weaker now. Lost the east to the Armu, north's already going. What in hell are we going to do with the Ancar?"

"Oh, come, come," Sulun felt obliged to put in. It was all getting too grim, too desperately grim. "Sabis's got more people now than it did then. A bigger army than it's ever had. You can't say it's weaker."

"Where'd it get those people?" Zeren gave him a sad half-smile and idly brushed bread crumbs off the leather strips of his armor skirt. "Same place it got me. Collapsing borders. Lost provinces. Where's the trade that used to feed the world, with the east torn up by invasions and internal squabbles and border wars? Where's the food coming from now? Jarrya-south. Jarrya-north is gone. And overseas from the south. But where's the sea trade in general, with that rat's nest of pirates raiding everything that comes near Sakar?"

Yanados flinched visibly; drew her arms off the table. "What choice did the fleet have?" she snapped. "When the old navy was betrayed in that damned Pergian coup, who offered to pay them? Who offered them a port? Where else could they go?"

Sulun raised an eyebrow. Stranger and stranger things, on this inauspicious day. Just how, he wondered, did his apprentice Yanados happen to know so much history—and so much about the lamentable affairs of Sakar? Yanados never had really said much about where she had come from when she turned up asking apprenticeship with Shibari's house tutor-cum-engineer. She had just given the general impression that her family had been merchants in Cerinde, or maybe Alise. But what if . . . ?

"Doesn't matter now," Zeren said. "Fleet's gone. What does matter is that Sakar harbors a legion of pirate ships, and they've sliced a good piece out of the sea trade, no matter if they're hunting supplies or just damned well looting. Just ask Sulun how much your master Shibari's lost this last year on pirated cargoes."

Yanados fell silent. Shibari was indeed neck deep in clamoring debts. And that was something none of them liked to think about.

There was profit to be had. Sulun knew, for instance, there was a big cargo coming in from Ista—big cargo, big profit in the shortages that plagued Sabis.

But even if the ships clung to the south coast all the way up to the coast of Mez, there was still the risk the Sakar pirates would raid them.

And if that happened, if Master Shibari lost that investment—

"The point is," the soldier went on, "Sabis is poorer and weaker today than it was when the Armu came down. Fifty years ago the center of the empire fought off the invading barbarians, but is it going to be lucky twice?"

"There's still the wizards!" Doshi said.

"There's their wizards," Zeren said. "Who're you going to bet on?"

Worse and worse. A man who worked with firepowder didn't like to go far down that train of thought. The poets made stories about wizards who could rain down fire and smoke on their enemies, but that wasn't real. What was, was your wizards sat down and ill-wished your enemies and good-wished your side, and their wizards sat down and did the same thing only in the other direction, and if your wizards were more powerful than their wizards, then everything that could go wrong on their side went wrong and everything that could go wrong on your side didn't.

If a piece of harness had a flaw, if a wheel could come off, magery could find it—and there was no way to tell when a wheel fell off your cart whether it was bad luck or somebody's bad-wishing; if a spark was remotely possible, for instance, too close to the firepowder. . . .

Sulun gave a little shudder.

Not that he believed the neighbors could or would hire anybody . . .

Not that he believed that anybody they could afford was more than Arizun had been; or even, if that Anybody had real magery, that anybody could out-mage master Shibari's house wizard . . .

Which ought to let a man stop worrying and do his work, and not think about things like that. Natural philosophy didn't have to compass magery; by its very definition, natural philosophy didn't have to worry about things like that. The wizards did, and because they did, you just did the best you could in the natural world and didn't leave any flaws for the mages to get a foothold in; that was the first and best defense.

Of course, if you worried that hex could hex you right into making a flaw in the first place. . . .

A man could go crazy down that track. So a man didn't think about it when he struck a spark from the tinderbox.

" . . . still wizards," Zeren scoffed. "And they have wizards." The soldier drained his cup and swept the room with a long, sad glance. "Sulun, my delightful little philosopher friend, Sabis desperately needs one wizard-factor that will give it the advantage over a vast horde of dangerously good foot soldiers. Some wizard-factor like this little toy of yours. Give me a hundred of these, a hundred that can be fired over and over without blowing themselves to the nine hells, and I could turn even the Ancar."

There was a long moment's silence, wherein Omis kept running his fingers through his curls, and saying over and over, "It's the seam. The seam never holds. But how do you make a tube without a seam?"

And Yanados said, "And where do we get enough firepowder for a hundred bombards? Charcoal, that's no problem. Saltpeter in every old dungheap. But sulfur, now . . ."

Doshi pushed his cup across the table. "Omis?" he said timidly. "Maybe like this?"

"Huh?" Omis asked. "Like what?"

"A tube. Imagine this cup deeper, longer, more of a tube. There's no seam in it. Look."

Omis picked up the empty tin cup. "No seam, true. But it's only half a ball shape, hammered out of a flat sheet onto a form. Tin-smithery. You couldn't hammer it much deeper, let alone in a tube-shape. You stretch it. You fold it . . ." He turned the empty cup in his hand, studying its shape and its construction. "Thin metal. Bending metal. Thin enough to hammer around a form is thin enough to burst in the charge. But if it wasn't hammered . . ."

"Where do you find sulfur?" Yanados was wondering. "I know you mine it. But from what sort of land? Mountains? Seashores? Where do they find it?"

"Near certain kinds of hot springs," Sulun said absently, scratching his chin. He had an appointment with Shibari: he had to shave, go back up to the big house with the accounts and explain his expenses. Shibari was anxious about mounting expenses and little return from this house Shibari's dwindling resources maintained for Sulun and his disciples and hangers-on in this waterfront neighborhood—a laboratorium, as Sulun had called it in laying out his plans and his diagrams and his financial requirements, in a neighborhood, as Sulun had also put it, more tolerant of the unusual and the noisy. Sulun's stomach was upset.

Yanados: "What kind of hot springs?"

"Hot springs in certain mountains," Sulun said, thinking still about those accounts, "the sort where one also finds black glass."

"Maybe not hammered at all," Omis murmured, turning the cup faster and faster in his hands. "Cast? But you can't get the impurities out without hammering. Got to start with twenty-times-hammered iron, a sheet or a rod or a block . . . Maybe drilled? But what could drill iron?"

"Find your answer soon, friends," Zeren muttered under his breath, "find it soon or not at all."