My partner Larry Niven and I have written five novels in collaboration. Whenever we go to conventions, we are inevitably asked "How do you two work together?"

We always answer in unison: "Superbly."

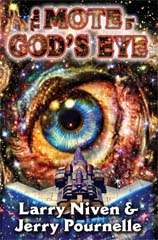

The first book Larry Niven and I wrote together was called MOTELIGHT. It opened with a battle between rebels and Imperial troops.

It was quite a good battle; the problem was that the battle wasn't really relevant to the main theme of the novel, and the book was more than long enough already. Eventually we solved the problem: we cut about 60,000 words out of MOTELIGHT. We also changed the name to THE MOTE IN GOD'S EYE, under which title the book has done very well indeed.

Scenes chopped from a novel don't usually make a story; but among the scenes we cut was that introductory battle, which was a complete story all by itself. The novel assumes that the battle happened as originally presented; but the actual story has never been published until now.

The tradition of military honor is very old and very strong, and with good reason. Total war is seldom just war; while a just cause has considerable military value to inspire the army and populace.

Query: can military honor be more important than the cause you fight for?

"Throughout the past thousand years of history it has been traditional to regard the Alderson Drive as an unmixed blessing. Without the faster than light travel Alderson's discoveries made possible, humanity would have been trapped in the tiny prison of the Solar System when the Great Patriotic Wars destroyed the CoDominium on Earth. Instead, we had already settled more than two hundred worlds."

"A blessing, yes. We might now be extinct were it not for the Alderson Drive. But unmixed? Consider. The same tramline effect that colonized the stars, the same interstellar contacts that allowed the formation of the First Empire, allow interstellar war. The worlds wrecked in two hundred years of Secession Wars were both settled and destroyed by ships using the Alderson Drive."

"Because of the Alderson Drive we need never consider the space between the stars. Because we can shunt between stellar systems in zero time, our ships and ships' drives need cover only interplanetary distances. We say that the Second Empire of Man rules two hundred worlds and all the space between, over fifteen million cubic parsecs . . ."

"Consider the true picture. Think of myriads of tiny bubbles, very sparsely scattered, rising through a vast black sea. We rule some of the bubbles. Of the waters we know nothing. . ."

—from a speech delivered by Dr. Anthony Horvath

at the Blaine Institute, A.D. 3029.

Any damn fool can die for his country.

General George S. Patton.

The Union Republic War Cruiser Defiant lay nearly motionless in space a half billion kilometers from Beta Hortensi. She turned slowly about her long axis.

Stars flowed endlessly upward with the spin of the ship, as if Defiant were falling through the universe. Captain Herb Colvin saw them as a battle map, infinitely dangerous. Defiant hung above him in the viewport, its enormous mass ready to fall on him and crush him, but after years in space he hardly noticed.

Hastily constructed and thrown into space, armed as an interstellar cruiser but without the bulky Alderson Effect engines which could send her between the stars, Defiant had been assigned to guard the approaches to New Chicago from raids by the Empire. The Republic's main fleet was on the other side of Beta Hortensi, awaiting an attack they were sure would come from that quarter. The path Defiant guarded sprang from a red dwarf star four-tenths of a light year distant. The tramline had never been plotted. Few within New Chicago's government believed the Empire had the capability to find it, and fewer thought they would try.

Colvin strode across his cabin to the polished steel cupboard. A tall man, nearly two meters in height, he was thin and wiry, with an aristocratic nose that many Imperial lords would have envied. A shock of sandy hair never stayed combed, but he refused to cover it with a uniform cap unless he had to. A fringe of beard was beginning to take shape on his chin. Colvin had been clean-shaven when Defiant began its patrol twenty-four weeks ago. He had grown a beard, decided he didn't like it and shaved it off, then started another. Now he was glad he hadn't taken the annual depilation treatments. Growing a beard was one of the few amusements available to men on a long and dreary blockade.

He opened the cupboard, detached a glass and bottle from their clamps, and took them back to his desk. Colvin poured expertly despite the Coriolis effect that could send carelessly poured liquids sloshing to the carpets. He set the glass down and turned toward the viewport.

There was nothing to see out there, of course. Even the heart of it all, New Chicago—Union! In keeping with the patriotic spirit of the Committee of Public Safety, New Chicago was now called Union. Captain Herb Colvin had trouble remembering that, and Political Officer Gerry took enormous pleasure in correcting him every damned time.—Union was the point of it all, the boredom and the endless low-level fear; but Union was invisible from here. The sun blocked it even from telescopes. Even the red dwarf, so close that it had robbed Beta Hortensi of its cometary halo, showed only as a dim red spark. The first sign of attack would be on the bridge screens long before his eyes could find the black-on-black point that might be an Imperial warship.

For six months Defiant had waited, and the question had likewise sat waiting in the back of Colvin's head.

Was the Empire coming?

The Secession War that ended the first Empire of Man had split into a thousand little wars, and those had died into battles. Throughout human space there were planets with no civilization, and many more with too little to support space travel.

Even Sparta had been hurt. She had lost her fleets, but the dying ships had defended the Capital; and when Sparta began to recover, she recovered fast.

Across human space men had discovered the secrets of interstellar travel. The technology of the Langston Field was stored away in a score of Imperial libraries; and this was important because the Field was discovered in the first place through a series of improbable accidents to men in widely separated specialties. It would not have been developed again.

With Langston Field and Alderson Drive, the Second Empire rose from the ashes of the First. Every man in the new government knew that weakness in the First Empire had led to war—and that war must not happen again. This time all humanity must be united. There must be no worlds outside the Imperium, and none within it to challenge the power of Emperor and Senate. Mankind would have peace if worlds must die to bring it about.

The oath was sworn, and when other worlds built merchantmen, Sparta rebuilt the Fleet and sent it to space. Under the fanatical young men and women humanity would be united by force. The Empire spread around Crucis and once again reached behind the Coal Sack, persuading, cajoling, conquering and destroying where needed.

New Chicago had been one of the first worlds reunited with the Empire of Man. The revolt must have come as a stunning surprise. Now Captain Herb Colvin of the United Republic waited on blockade patrol for the Empire's retaliation. He knew it would come, and could only hope that Defiant would be ready.

He sat in the enormous leather chair behind his desk, swirling his drink and letting his gaze alternate between his wife's picture and the viewport. The chair was a memento from the liberation of the Governor General's palace on New Chicago. (On Union!) It was made of imported leathers, worth a fortune if he could find the right buyer. The Committee of Public Safety hadn't realized its value.

Colvin looked from Grace's picture to a pinkish star drifting upward past the viewport, and thought of the Empire's warships. Would they come through here, when they came? Surely they were coming.

In principal Defiant was a better ship than she'd been when she left New Chicago. The engineers had automated all the routine spacekeeping tasks, and no United Republic spacer needed to do a job that a robot could perform. Like all of New Chicago's ships, and like few of the Imperial Navy's, Defiant was as automated as a merchantman.

Colvin wondered. Merchantmen do not fight battles. A merchant captain need not worry about random holes punched through his hull. He can ignore the risk that any given piece of equipment will be smashed at any instant. He will never have only minutes to keep his ship fighting or see her destroyed in an instant of blinding heat.

No robot could cope with the complexity of decisions damage control could generate, and if there were such a robot it might easily be the first item destroyed in battle. Colvin had been a merchant captain and had seen no reason to object to the Republic's naval policies, but now that he had experience in warship command, he understood why the Imperials automated as little as possible and kept the crew in working routine tasks: washing down corridors and changing air filters, scrubbing pots and inspecting the hull. Imperial crews might grumble about the work, but they were never idle. After six months, Defiant was a better ship, but . . . she had lifted out from . . . Union with a crew of mission-oriented warriors. What were they now?

Colvin leaned back in his comfortable chair and looked around his cabin. It was too comfortable. Even the captain—especially the captain!—had little to do but putter with his personal surroundings, and Colvin had done all he could think of.

It was worse for the crew. They fought, distilled liquor in hidden places, gambled for stakes they couldn't afford, and were bored. It showed in their discipline. There wasn't any punishment duty either, nothing like cleaning heads or scrubbing pots, the duties an Imperial skipper might assign his crewmen. Aboard Defiant it would be make-work, and everyone would know it.

He was thinking about another drink when an alarm trilled.

"Captain here," Colvin said.

The face on the viewscreen was flushed. "A ship, sir," the Communications officer said. "Can't tell the size yet, but definitely a ship from the red star."

Colvin's tongue dried up in an instant. He'd been right all along, through all these months of waiting, and the flavor of being right was not pleasant. "Right. Sound battle stations. We'll intercept." He paused a moment as Lieutenant Susack motioned to other crew on the bridge. Alarms sounded through Defiant. "Make a signal to the fleet, Lieutenant."

"Aye aye, sir."

Horns were still blaring through the ship as Colvin left his cabin. Crewmen dove along the steel corridors, past grotesque shapes in combat armor. The ship was already losing her spin and orienting herself to give chase to the intruder. Gravity was peculiar and shifting. Colvin crawled along the handholds like a monkey.

The crew were waiting. "Captain's on the bridge," the duty NCO announced. Others helped him into armor and dogged down his helmet. He had only just strapped himself into his command seat when the ship's speakers sounded.

"ALL SECURE FOR ACCELERATION. STAND BY FOR ACCELERATION."

"Intercept," Colvin ordered. The computer recognized his voice and obeyed. The joltmeter swung hard over and acceleration crushed him to his chair. The joltmeter swung back to zero, leaving a steady three gravities.

The bridge was crowded. Colvin's comfortable acceleration couch dominated the spacious compartment. In front of him three helmsmen sat at inactive controls, ready to steer the ship if her main battle computer failed. They were flanked by two watch officers. Behind him were runners and talkers, ready to do the Captain's will when he had orders for them.

There was one other.

Beside him was a man who wasn't precisely under Colvin's command. Defiant belonged to Captain Colvin. So did the crew—but he shared that territory with Political Officer Gerry. The Political Officer's presence implied distrust in Colvin's loyalty to the Republic. Gerry had denied this, and so had the Committee of Public Safety; but they hadn't convinced Herb Colvin.

"Are we prepared to engage the enemy, Captain?" Gerry asked. His thin and usually smiling features were distorted by acceleration.

"Yes. We are doing so now." Colvin said. What the hell else could they be doing? But of course Gerry was asking for the recorders.

"What is the enemy ship?"

"The hyperspace wake's just coming into detection range now, Mister Gerry." Colvin studied the screens. Instead of space with the enemy ship black and invisible against the stars, they showed a series of curves and figures, probability estimates, tables whose entries changed even as he watched. "I believe it's a cruiser, same class as ours," Colvin said.

"Even match?"

"Not exactly," Colvin said. "He'll be carrying interstellar engines. That'll take up room we use for hydrogen. He'll have more mass for his engines to move, and we'll have more fuel. He won't have a lot better armament than we do, either." He studied the probability curves and nodded. "Yeah, that looks about right. What they call a 'Planet Class' cruiser."

"How soon before we fight?" Gerry gasped. The acceleration made each word an effort.

"Few minutes to an hour. He's just getting under way after coming out of hyperdrive. Too damn bad he's so far away, we'd have him right if we were a little closer."

"Why weren't we?" Gerry demanded.

"Because the tramline hasn't been plotted," Colvin said. And I'm speaking for the record. Better get it right, and get the sarcasm out of my voice. "I requested survey equipment, but none was available. We were therefore required to plot the Alderson entry point using optics alone. I would be much surprised if anyone could have made a better estimate using our equipment."

"I see," Gerry said. With an effort he touched the switch that gave him a general intercom circuit. "Spacers of the Republic, your comrades salute you! Freedom!"

"Freedom!" came the response. Colvin didn't think more than half the crew had spoken, but it was difficult to tell.

"You all know the importance of this battle," Gerry said. "We defend the back door of the Republic, and we are alone. Many believed we need not be here, that the Imperials would never find this path to our homes. That ship shows the wisdom of the government."

Had to get that in, didn't you? Colvin chuckled to himself. Gerry expected to run for office, if he lived through the coming battles.

"The Imperials will never make us slaves! Our cause is just, for we seek only the freedom to be left alone. The Empire will not permit this. They wish to rule the entire universe, forever. Spacers, we fight for liberty!"

Colvin looked across the bridge to the watch officer and lifted an eyebrow. He got a shrug for an answer. Herb nodded. It was hard to tell the effect of a speech. Gerry was said to be good at speaking. He'd talked his way into a junior membership on the Committee of Public Safety that governed the Republic.

A tiny buzz sounded in Colvin's ear. The Executive Officer's station was aft, in an auxiliary control room, where he could take over the ship if something happened to the main bridge.

By Republic orders Gerry was to hear everything said by and to the captain during combat, but Gerry didn't know much about ships. Commander Gregory Halleck, Colvin's exec, had modified the intercom system. Now his voice came through, the flat nasal twang of New Chicago's outback. "Skipper, why don't he shut up and let us fight?"

"Speech was recorded, Greg," Colvin said.

"Ah. He'll play it for the city workers," Halleck said. "Tell me, skipper, just what chance have we got?"

"In this battle? Pretty good."

"Yeah. Wish I was so sure about the war."

"Scared, Greg?"

"A little. How can we win?"

"We can't beat the Empire," Colvin said. "Not if they bring their whole fleet in here. But if we can win a couple of battles, the Empire'll have to pull back. They can't strip all their ships out of other areas. Too many enemies. Time's on our side, if we can buy some."

"Yeah. Way I see it, too. Guess it's worth it. Back to work."

It had to be worth it, Colvin thought. It just didn't make sense to put the whole human race under one government. Some day they'd get a really bad Emperor. Or three Emperors all claiming the throne at once. Better to put a stop to this now, rather than leave the problem to their grandchildren.

The phones buzzed again. "Better take a good look, skipper," Halleck said. "I think we got problems."

The screens flashed as new information flowed. Colvin touched other buttons in his chair arm. Lt. Susack's face swam onto one screen. "Make a signal to the fleet," Colvin said. "That thing's bigger than we thought. This could be one hell of a battle."

"Aye aye," Susack said. "But we can handle it."

"Sure," Colvin said. He stared at the updated information and frowned.

"What is out there, Captain?" Gerry asked. "Is there reason for concern?"

"There could be," Colvin said. "Mister Gerry, that is an Imperial battle cruiser. General class, I'd say." As he told the political officer, Colvin felt a cold pit in his guts.

"And what does that mean?"

"It's one of their best," Colvin said. "About as fast as we are. More armor, more weapons, more fuel. We've got a fight on our hands."

"Launch observation boats. Prepare to engage," Colvin ordered. Although he couldn't see it, the Imperial ship was probably doing the same thing. Observation boats didn't carry much for weapons, but their observations could be invaluable when the engagement began.

"You don't sound confident," Gerry said.

Colvin checked his intercom switches. No one could hear him but Gerry. "I'm not," he said. "Look, however you cut it, if there's an advantage that ship's got it. Their crew's had a chance to recover from their hyperspace trip, too." If we'd had the right equipment—No use thinking about that.

"What if it gets past us?"

"Enough ships might knock it out, especially if we can damage it, but there's no single ship in our fleet that can fight that thing one-on-one and expect to win."

He paused to let that sink in.

"Including us."

"Including us. I didn't know there was a battle cruiser anywhere in the trans-Coalsack region."

"Interesting implications," Gerry said.

"Yeah. They've brought one of their best ships. Not only that, they took the trouble to find a back way. Two new Alderson tramlines. From the red dwarf to us, and a way into the red dwarf."

"Seems they're determined." Gerry paused a moment. "The Committee was constructing planetary defenses when we lifted out."

"They may need them. Excuse me . . ." Colvin cut the circuit and concentrated on his battle screens.

The master computer flashed a series of maneuver strategies, each with the odds for success if adopted. The probabilities were only a computer's judgment, however. Over there in the Imperial ship was an experienced human captain who'd do his best to thwart those odds while Colvin did the same. Game theory and computers rarely consider all the possibilities a human brain can conceive.

The computer recommended full retreat and sacrifice of the observation boats—and at that gave only an even chance for Defiant. Colvin studied the board. "ENGAGE CLOSELY," he said.

The computer wiped the other alternatives and flashed a series of new choices. Colvin chose. Again and again this happened until the ship's brain knew exactly what her human master wanted, but long before the dialogue was completed the ship accelerated to action, spewing torpedoes from her ports to send H-bombs on random evasion courses toward the enemy. Tiny lasers reached out toward enemy torpedoes, filling space with softly glowing threads of bright color.

Defiant leaped toward her enemy, her photon cannons pouring out energy to wash over the Imperial ship. "Keep it up, keep it up," Colvin chanted to himself. If the enemy could be blinded, her antennas destroyed so that her crew couldn't see out through her Langston Field to locate Defiant, the battle would be over.

Halleck's outback twang came through the earphones. "Looking good, boss."

"Yeah." The very savagery of unexpected attack by a smaller vessel had taken the enemy by surprise. Just maybe—

A blaze of white struck Defiant to send her screens up into the orange, tottering towards yellow for an instant. In that second Defiant was as blind as the enemy, every sensor outside the Field vaporized. Her boats were still there, though, still sending data on the enemy's position, still guiding torpedoes.

"Bridge, this is damage control."

"Yeah, Greg."

"Hulled in main memory bank area. I'm getting replacement elements in, but you better go to secondary computer for a while."

"Already done."

"Good. Got a couple other problems, but I can handle them."

"Have at it." Screens were coming back on line. More sensor clusters were being poked through the Langston Field on stalks. Colvin touched buttons in his chair arm. "Communications. Get number three boat in closer."

"Acknowledged."

The Imperial ship took evasive action. She would cut acceleration for a moment, turn slightly, then accelerate again, with constantly changing drive power. Colvin shook his head. "He's got an iron crew," he muttered to Halleck. "They must be getting the guts shook out of them."

Another blast rocked Defiant. A torpedo had penetrated her defensive fire to explode somewhere near the hull. The Langston Field, opaque to radiant energy, was able to absorb and redistribute the energy evenly throughout the Field; but at cost. There had been an overload at the place nearest the bomb: energy flaring inward. The Langston Field was a spaceship's true hull. Its skin was only metal, designed only to hold pressure. Breach it and—

"Hulled again aft of number two torpedo room," Halleck reported. "Spare parts, and the messroom brain. We'll eat basic protocarb for a while."

"If we eat at all." Why the hell weren't they getting more hits on the enemy? He could see the Imperial ship on his screens, in the view from number two boat. Her field glowed orange, wavering to yellow, and there were two deep purple spots, probably burnthroughs. No way to tell what lay under those areas. Colvin hoped it was something vital.

His own Field was yellow tinged with green. Pastel lines jumped between the two ships. After this was over, there would be time to remember just how pretty a space battle was. The screens flared, and his odds for success dropped again, but he couldn't trust the computer anyway. He'd lost number three boat, and number one had ceased reporting.

The enemy ship flared again as Defiant scored a hit, then another. The Imperial's screens turned yellow, then green; as they cooled back toward red another hit sent them through green to blue. "Torps!" Colvin shouted, but the master computer had already done it. A stream of tiny shapes flashed toward the blinded enemy. "Pour it on!" Colvin screamed. "Everything we've got!" If they could keep the enemy blind, keep him from finding Defiant while they poured energy into his Field, they could keep his screens hot enough until torpedoes could get through. Enough torpedoes would finish the job. "Pour it on!"

The Imperial ship was almost beyond the blue, creeping toward the violet. "By God we may have him!" Colvin shouted.

The enemy maneuvered again, but the bright rays of Defiant's lasers followed, pinning the glowing ship against the star background. Then the screens went blank.

Colvin frantically pounded buttons. Nothing happened. Defiant was blind. "Eyes! How'd he hit us?" he demanded.

"Don't know." Susack's voice was edged with fear. "Skipper, we've got problems with the detectors. I sent a party out but they haven't reported—"

Halleck came on. "Imperial boat got close and hit us with torps."

Blind. Colvin watched his screen color indicators. Bright orange and yellow, with a green tint already visible. Acceleration warnings hooted through the ship as Colvin ordered random evasive action. The enemy would be blind too. Now it was a question of who could see first. "Get me some eyes." he said. He was surprised at how calm his voice was.

"Working on it," Halleck said. "I've got minimal sight back here. Maybe I can locate him."

"Take over gun direction," Colvin said. "What's with the computer?"

"I'm not getting damage reports from that area," Halleck said. "I have men out trying to restore internal communications, and another party's putting out antennas—only nobody really wants to go out to the hull edge and work, you know."

"Wants!" Colvin controlled blind rage. Who cared what the crew wanted? His ship was in danger!

Acceleration and jolt warnings sounded continuously as Defiant continued evasive maneuvers. Jolt, acceleration, stop, turn, jolt—

"He's hitting us again." Susack sounded scared.

"Greg?" Colvin demanded.

"I'm losing him. Take over, skipper."

Defiant writhed like a beetle on a pin as the deadly fire followed her through maneuvers. The damage reports came as a deadly litany. "Partial collapse, after auxiliary engine room destroyed. Hulled in three places in number five tankage area, hydrogen leaking to space. Hulled in the after recreation room."

The screens were electric blue when the computer cut the drives. Defiant was dead in space. She was moving at more than a hundred kilometers per second, but she couldn't accelerate.

"See anything yet?" Colvin asked.

"In a second," Halleck replied. "There. Wups. Antenna didn't last half a second. He's yellow. Out there on our port quarter and pouring it on. Want me to swing the main drive in that direction? We might hit him with that."

Colvin examined his screens. "No. We can't spare the power." He watched a moment more, then swept his hand across a line of buttons.

All through Defiant nonessential systems died. It took power to maintain the Langston Field, and the more energy the Field had to contain the more internal power was needed to keep the Field from radiating inward. Local overloads produced burnthroughs, partial collapses sending bursts of energetic photons to punch holes through the hull. The Field moved toward full collapse, and when that happened, the energies it contained would vaporize Defiant. Total defeat in space is a clean death.

The screens were indigo and Defiant couldn't spare power to fire her guns or use her engines. Every erg was needed simply to survive.

"We'll have to surrender," Colvin said. "Get the message out."

"I forbid it!"

For a moment Colvin had forgotten the political officer.

"I forbid it!" Gerry shouted again. "Captain, you are relieved from command. Commander Halleck, engage the enemy! We cannot allow him to penetrate to our homeland!"

"Can't do that, sir," Halleck said carefully. The recorded conversation made the executive officer a traitor, as Colvin was the instant he'd given the surrender order.

"Engage the enemy, Captain." Gerry spoke quietly. "Look at me, Colvin."

Herb Colvin turned to see a pistol in Gerry's hands. It wasn't a sonic gun, not even a chemical dart weapon as used by prison guards. Combat armor would stop those. This was a slugthrower—no. A small rocket launcher, but it looked like a slugthrower. Just the weapon to take to space.

"Surrender the ship," Colvin repeated. He motioned with one hand. Gerry looked around, too late, as the quartermaster pinned his arms to his sides. A captain's bridge runner launched himself across the cabin to seize the pistol.

"I'll have you shot for this!" Gerry shouted. "You've betrayed everything. Our homes, our families—"

"I'd as soon be shot as surrender," Colvin said. "Besides, the Imperials will probably do for both of us. Treason, you know. Still, I've a right to save the crew."

Gerry said nothing.

"We're dead, Mister. The only reason they haven't finished us off is we're so bloody helpless the Imperial commander's held off firing the last wave of torpedoes to give us a chance to quit. He can finish us off any time."

"You might damage him. Take him with us, or make it easier for the fleet to deal with him—"

"If I could, I'd do that. I already launched all our torpedoes. They either got through or they didn't. Either way, they didn't kill him, since he's still pouring it on us. He has all the time in the world—look, damn it! We can't shoot at him, we don't have power for the engines, and look at the screens! Violet! Don't you understand, you blithering fool, there's no further place for it to go! A little more, a miscalculation by the Imperial, some little failure here, and that field collapses."

Gerry stared in rage. "Maybe you're right."

"I know I'm right. Any progress, Susack?"

"Message went out," the communications officer said. "And they haven't finished us."

"Right." There was nothing else to say.

A ship in Defiant's situation, her screens overloaded, bombarded by torpedoes and fired on by an enemy she cannot locate, is utterly helpless; but she has been damaged hardly at all. Given time she can radiate the screen energies to space. She can erect antennas to find her enemy. When the screens cool, she can move and she can shoot. Even when she has been damaged by partial collapses, her enemy cannot know that.

Thus, surrender is difficult and requires a precise ritual. Like all of mankind's surrender signals it is artificial, for man has no surrender reflex, no unambiguous species-wide signal to save him from death after defeat is inevitable. Of the higher animals, man is alone in this.

Stags do not fight to the death. When one is beaten, he submits, and the other allows him to leave the field. The three spine stickleback, a fish of the carp family, fights for its mates but recognizes the surrender of its enemies. Siamese fighting fish will not pursue an enemy after he ceases to spread his gills.

But man has evolved as a weapon-using animal. Unlike other animals, man's evolution is intimately bound with weapons and tools; and weapons can kill farther than man can reach. Weapons in the hand of a defeated enemy are still dangerous. Indeed, the Scottish skean dhu is said to be carried in the stocking so that it may be reached as its owner kneels in supplication. . . .

Defiant erected a simple antenna suitable only for radio signals. Any other form of sensor would have been a hostile act and would earn instant destruction. The Imperial captain observed and sent instructions.

Meanwhile, torpedoes were being maneuvered alongside Defiant. Colvin couldn't see them. He knew they must be in place when the next signal came through. The Imperial ship was sending an officer to take command.

Colvin felt some of the tension go out of him. If no one had volunteered for the job, Defiant would have been destroyed.

Something massive thumped against the hull. A port had already been opened for the Imperial. He entered carrying a bulky object: a bomb.

"Midshipman Horst Staley, Imperial Battlecruiser MacArthur," the officer announced as he was conducted to the bridge. Colvin could see blue eyes and blonde hair, a young face frozen into a mask of calm because its owner did not trust himself to show any expression at all. "I am to take command of this ship, sir."

Captain Colvin nodded. "I give her to you. You'll want this," he added, handing the boy the microphone. "Thank you for coming."

"Yes, sir." Staley gulped noticeably, then stood at attention as if his captain could see him. "Midshipman Staley reporting, sir. I am on the bridge and the enemy has surrendered." He listened for a few seconds, then turned to Colvin. "I am to ask you to leave me alone on the bridge except for yourself, sir. And to tell you that if anyone else comes on the bridge before our Marines have secured this ship, I will detonate the bomb I carry. Will you comply?"

Colvin nodded again. "Take Mr. Gerry out, quartermaster. You others can go, too. Clear the bridge."

The quartermaster led Gerry toward the door. Suddenly the political officer broke free and sprang at Staley. He wrapped the midshipman's arms against his body and shouted, "Quick, grab the bomb! Move! Captain, fight your ship, I've got him!"

Staley struggled with the political officer. His hand groped for the trigger, but he couldn't reach it. The mike had also been ripped from his hands. He shouted at the dead microphone.

Colvin gently took the bomb from Horst's imprisoned hands. "You won't need this, son," he said. "Quartermaster, you can take your prisoner off this bridge." His smile was fixed, frozen in place, in sharp contrast to the midshipman's shocked rage and Gerry's look of triumph.

The spacers reached out and Horst Staley tried to escape, but there was no place to go as he floated in free space. Suddenly he realized that the spacers had seized his attacker, and Gerry was screaming.

"We've surrendered, Mister Staley," Colvin said carefully. "Now we'll leave you in command here. You can have your bomb, but you won't be needing it."