THE LEGEND OF THE

THREE KINGS

Rationalists predicted that religion would be the first thing to fall when humanity finally went to the stars and found no gods, no heaven or hell, that could not be explained by physics and the other sciences. Scientists never had been all that good at predicting or understanding human culture and sociology; they never even noticed that, when they finally went out there, every deity and supernatural belief system known at the time went right with them.

Humanity was late to the stars, considering how young in its life it had begun the quest, but, like all things it had done, once it decided to go and had the means, it went like wildfire.

The discovery of the wormgate system and the way it could stabilize and link wormholes, which folded space and took you many times faster than light by the simple method of stepping around it, made space travel efficient and affordable.

First out were the unmanned, super-hardened ships that could withstand the forces within a naturally occurring wormhole and exploit it, go through, and establish a temporary stabilizing gate on the other side. Then came the follow-ups, mostly robotics with some human supervision, who would convert that makeshift gate into a permanent and optimized one. Then a small maintenance station both for the gate and for ships that might come after was built and stocked, so that parts and labor were available as needed.

Natural wormholes created weaknesses within several parsecs, allowing other holes to form. Most were quite small and many were highly unstable, but the little probes punched through and were successful, at least most of the time.

Next came the government types, of course, in quasi-military-equipped highly reinforced ships, looking for alien lifeforms and new worlds to exploit.

And they found them! Not exactly alien civilizations, but certainly alien lifeforms in incredible abundance in a universe that seemed filled with potentially human-habitable planets. Much of the alien life was basic and primitive, the equivalent of Earth's insects and animal and plant life, strange as it might be to the humans who went out there. Still, while nothing was a precise match to Earth forms, and much was surprising and even revolutionary to science, nothing really broke the rules.

Nothing also seemed to have evolved intelligence, let alone civilization, beyond the most rudimentary; evolution was borne out, but the requirement for a fast-thinking brain seemed to be a low priority in nature's schemes. Humanity's fickle interest in the exploration program waned, as it always tended to do in anything that went along without real surprises, and the scientists and corporations who depended upon it sought new methods of funding. Ultimately, they came up with the idea of selling off some of the best planets to interest groups back on Earth and on the few planets that had been developed to bleed off excess Earth population. It seemed an outrageous and unworkable idea. How many groups would even want their own planet, anyway? After all, even if they were livable, the only reason to sell the planets at all would be because science and government had decided that the worlds had nothing profitable to offer. And who could afford it? Certainly all of the worlds in question could be used in a self-supporting mode, assuming settlers could import or develop Earth plants and animals that could thrive there and use the world's mineral resources for building. But all such a program would offer would be a return to a more primitive life with little to bargain with.

The answer was, just about every group and leader with a dream or a vision or a political theory wanted a world. Every established religious group, and every dissident religious group, and every cult open and secret that had survived history or had emerged from it wanted their own world. And they all seemed to have amazing abilities to raise sufficient funds to get one, too.

Soon there were hundreds of settled worlds, spread all over the near galaxy, connected by a network of self-powered and self-maintained wormgates that, mapped, looked like some drunken spider's webbing. But the one thing they weren't, not really, was independent.

The Earth System Combine wanted a single level of control, a single military force, and control of the economy of the entire expanding system, if only to pay for its expenses and expansion. But over such a vast distance and with so many quasi-independent "colonies," direct political and military control would be expensive and impractical. Instead, the economic system was divided so that none of the worlds established out there were in more than the most basic sense self-sufficient. Oh, most could certainly maintain a subsistence living, some much better than that, but for the latest technology, the cutting edge of what was possible, they were made cleverly interdependent, with no single world having more than a tiny part of the whole. Any worlds that matured and chafed at interstellar rules and regulations, or balked at their share of the "user and facilitation fees" paid to the Combine, was welcome to drop out. It was then that they discovered how dependent they really were, and what it was like to be on your own in a cleverly constructed system that even controlled access to its own parts. If you weren't a member, the costs and fees were huge, and prohibitive to a degree.

Some tried it anyway, but no terraforming was that far along or that absolute, and none of the worlds were true Earthly paradises. The ones who stayed out and cut all ties were often revisited out of curiosity decades later by Combine ships only to be found worlds with no human survivors.

The skills that had originally made humans dominate their home planet were now dead; nobody knew them anymore. The machines did it, but who programmed and maintained the machines? And what happened if no more came?

And each rebel thus became an example, all without firing a shot. The Combine grew fat, and lazy, and rich, and complacent.

Nobody knew what had caused it, nor who. The best guess was one more grab for power by yet another faction back home who ran into a ruling clique who decided that if they couldn't have the power and control nobody else would. A miscalculation, a failure of intelligence or perhaps a misjudgment of will. Perhaps it was an unforeseen enemy in their midst or from somewhere else in the vast starfields. It didn't matter.

Whatever it was, what happened was that, one day, with no notice and no particular alarms, almost a third of the wormgate system, the part that led back toward Earth System and the headquarters of the Combine, simply stopped. Nothing more emerged from the gates, even though ordinarily traffic was brisk; and, perhaps as ominously, nothing that went into the gates after that one point ever was seen or heard from again.

Messenger probes went in and never came out. There was some indication that they might not have arrived anywhere.

It was the Great Silence.

Two thirds of the wormhole system, and part of the military and commercial fleets, remained working and intact, but it was the part that ran from the developing to the least developed points. There was no longer any direction, and the finely tuned interdependency that included the third now gone could not exist any longer. Worlds did not fall into savagery, at least not most of them, but they were far more on their own than before, and the ones who now ran what was left of the show were the ones with operating spaceships.

The trouble was, spaceships were a commodity that had originated strictly from the Combine and near Earth systems; there weren't any spaceship factories in the remaining two thirds, nor the automated systems to create them and power them safely. There was maintenance, yes, but that was it, and going through artificially enlarged and artificially maintained wormholes left little tolerance for error.

The military tended to become a force unto itself, claiming all jurisdiction over interstellar space and the gates, financing itself by taxing the commercial ships that still ran. The commercial ships became the prizes, trying to continue their runs, keep themselves safe and maintained, and avoid the military, potential pirates, and privateers at the same time.

Things were breaking down and fast. Only the most profitable worlds and markets were of interest; most of the other worlds were forgotten, neglected, or just ignored.

It was another century before the Supreme Cardinal of Vaticanus, a world maintained and developed as a religious retreat by the Roman Catholic Church before the Great Silence, became one of the first to try and put some order back into the system. Without contact with the Pope or even knowing for certain if there still was one, but maintaining out of faith that there had to be, the board of cardinals who'd run the retreat and seminary world had run things as they hoped God wished, awaiting a relinking with Earth. It hadn't come, and now they were finally using some of their wealth, some of their connections on the more developed colonies, and their backup of the vast Vatican library system to send out a few dedicated priests to try and find the lost worlds.

It was probably because his name really was Ishmael.

The small probe ship came out of the void with the keys to Heaven, Hell, and perhaps someplace in between; it brought with it evidence of fabulous riches and more, but what it didn't bring back was a road map to the stars.

Along with the spiritual part of humanity, the legends, both good and bad, had also survived, particularly among the few who still knew of or could follow the patterns of the scouts to the stars. Fear, doubt, and death were out there, it was true, but perhaps not only that. Somewhere out there, in stories and songs and legends from forgotten origins, were the Three Kings.

Every civilization had at least one such legend; every faith as well. It might be the kingdom of Prester John, or the fabled El Dorado, or, on a more ethereal plain, it might be called Paradise, Heaven, or a state of Nirvana. On a more secular level, it was the big one, the find of a lifetime, the jackpot, the ultimate strike. Nobody really knew what it looked like, but everyone had their own vision, their own dream, and their own deep-down conviction that, sooner or later, they would find it.

The major difference between all of those and the Three Kings was that almost everyone was convinced that the Three Kings existed, and there was in fact physical evidence of it. The trouble was, its location was as mysterious and mystical as any of the others.

Ishmael Hand was one of the breed of loners the church called Prophets and everybody else called scouts. Half human, half machine, merged into cybernetic ships that were almost organisms in and of themselves, able to build—or perhaps grow would be a better word—the probes and contact devices they required, these volunteers to go forever into the eternal void in search of the unknown had a million motives. Hand was a mystic, and not the only one in that category of scout; he had turned himself into the ultimate pilgrim, searching among the stars, praying, meditating when in between, looking for something that might be out there, might actually be within his own mind, or might not exist at all. To those who sent the volunteers out, the motive didn't matter, so long as the supply of them continued.

It was initially done entirely by machines; smart machines, machines that were every bit the observer and evaluator—but those machines proved lacking in several ways. They had never been living beings, born and raised in organic environments, feeling what organic sentient beings feel, understanding in non-academic ways what organic sentient beings really wanted or needed. They could only send back samples and reports; they could never send back impressions that others might understand and interpret. They could quantify, but they could not dream.

Sentient beings like the human Ishmael Hand, however, also had their limits, not just physical but mental and emotional as well, and they didn't live long enough to cover vast distances; nor did they have the precision and detail that cybernetic equipment could bring to a job. The marriage of creature and machine was, after much trial and error, found to be the perfect vehicle.

Within, of course, limits.

For if they were not a little bit mad when they left, they certainly were after centuries of roaming the vastness of the universe; yet their machine sides stayed precise and detailed. As time went on, it often became difficult to interpret all the data properly. . . .

Once an uncharted system was sighted, scouted, and thoroughly investigated, the procedure was simple. The ships themselves were almost organic; they could take in debris, dust, rock, whatever was out there and convert it to what was needed, just as their external scoops could turn some of it into interstellar fuels. From this material they grew small probes according to designs within their complex memory banks, and sent them everywhere in system. Every type of analysis was performed, every part of everything evaluated. The most dead of worlds could contain something of great or unique value.

Premiums, of course, were first and foremost lost colonies; then solid planets within the life zone that could be the source of new life or, if there was anything particularly interesting, could be turned with minimal cost or effort into new colonies. Beyond that, the ships looked for things they had never seen before, beautiful and unique creations, knowledge.

There was a lot of life in the galaxy; that was well known. The trouble was, only a minuscule portion of it had any brains at all; and of the handful of races bumped into by expanding humanity, none had been anything but primitive.

Ishmael Hand had recognized what he'd stumbled on almost immediately. Long before the Great Silence there were half-whispered tales of them, but never, until now, solid physical evidence of their existence. Three planets in the life zone that had not gone bad over the eons was just about unheard of; even two was almost never seen. That was why, Hand speculated, nobody had really found the Three Kings since early and messed-up machine-only scouts had first reported them.

Because the Three Kings weren't three planets, not exactly. There was one enormous planet, a world at the outer limits of even gas giants, and three moons, very different, yet each with thick, oxygen-rich atmospheres and water.

The largest one, bigger than the Earth, wasn't the sort of place you wanted to visit. As big as it was, it contained vast, active volcanic fields, and in some places the land was forever changing, floating and twisting where lava fractured it.

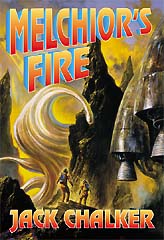

And yet there was water, even two vast oceans, making almost a dance of solidity and water, and then fire and flux, then water and solid land again, and then another fiery area. Much of the surface was concealed in clouds, but now and then there were breaks—and those breaks showed the bizarre and fractured landscape below. It was hot on its surface, even in the "cool" solid regions, but perhaps not too hot. There was vegetation, in a riot of colors, wherever it could cling and not be burned off or knocked off by internal forces. It wasn't a nice place to live and work, but it was fascinating if only because nobody, not Ishmael Hand nor the vastly larger and more complex thinking machines of the home empire he'd abandoned, could figure out how the heck a planet that dynamic and contradictory could possibly exist. Although the Three Kings name was ancient, it remained for the scout to make sense of it, and he called this huge planet Melchior.

And then there were the other large moons, among countless rather ordinary small ones. One of the larger ones was warm but not a raging madhouse like the huge planet below that held it captive; almost 25,000 kilometers at its equator, a small planet in captivity. It was a wonderland of islands large and small in a continuous sea, more than forty percent land yet with no major gaps, so that any part of the water could be called an ocean, nor land masses so huge that they might be considered continents. It was a world of lakes and islands, teeming with plants and perhaps small animals, wild, primitive, and beautiful. This moon Hand called Balshazzar.

The third moon also had an atmosphere, but it was farther out, cold, full of bizarre and twisted rocks and spires, great desertlike regions of red and gold and purple sand. Yet somehow, without large bodies of surface water, nor the thick vegetation that would normally go with such an atmosphere, it retained in the air a significant amount of water vapor that rose in the night from the ground in thick mists and vanished in the light, and oxygen, nitrogen, and many other elements needed for life. The atmosphere was thinner than humans liked it, but they could exist there, as they'd learned to exist atop three- and four-kilometer mountain ranges on their mother Earth and elsewhere. This third moon Hand christened Kaspar.

"None of the figures make a lot of sense, I admit," the scout's report said, "but it will make some careers to determine how these ecosystems work. God is having fun with us here, challenging us. I do not have the means to start solving these riddles, but I feel certain that you have ones who have more than that."

The worlds, in their own ways, also lived up to their ancient reputation, judging from the samples sent back.

Here was a small sack of apparently natural gems, gems as large as hens' eggs and colored in translucent emerald or ruby or sapphire, with centers of some different substance that, when viewed from different angles, seemed to form almost pictures or shapes—familiar ones, unique to each viewer, subjective and ever-changing devices of fascination. Machines could make synthetic copies that were almost but not quite like the real thing, of course—but the real thing was unique in nature and thus precious.

There was sand in exotic colors, mixed within containers but nonetheless unmixed, as if the colors refused to blend with each other and the individual grains appeared to prefer only their own company. The properties were electromagnetic in nature but would take a long time to yield up their secrets, particularly how such things could have come about in nature.

Plant samples at once familiar and yet so alien that they appeared to be able to convert virtually any kind of energy into food, including, if one was not careful, any living things that touched them. Rooted plants that nonetheless responded to sounds and actions and would attempt to bend away from probes or shears and whose own energy fields could distort instruments and short out standard analyzers.

But most fascinating of all were the Artifacts.

They were always afterwards called the Artifacts, with a capital "A," because there was nothing like them and no way to explain them. Ishmael Hand found no signs of any sentient lifeforms on any of the three worlds, nor ruins, nor any signs that anyone had ever been there before, but he, too, understood what was implied by the Artifacts.

They were not spectacular, yet they were the greatest of all finds. One was a simple cylinder, perfectly machined, with tolerances so small, with dimensions so perfect, that one had to go down almost to the atomic level to find a flaw. And it was machined out of an absolutely one hundred percent pure block of titanium.

It also looked very much as if it had been manufactured in a lab within the past few hours, yet the tag with it indicated that it was lying half buried in the surface. But the entire thing was coated, to the thickness of only a dozen atoms, in a hard coating that was close enough to one used in human manufacturing that it was inconceivable to think of it as natural.

The second was a gear, perhaps a half a meter around, with one hundred and eighty-two fine and perfect teeth. It, too, was machined just like the cylinder, to absolute perfection, and it, too, had the synthetic protective coating.

The third and final Artifact was a one-meter coil, made out of a totally synthetic and absolutely clear polymerlike substance and created to the same perfect tolerances as the other two. The coil had nineteen turns and its ends were smooth, not broken. The substance was unlike any that had ever been seen before, yet made of stuff that contemporary labs would have no trouble duplicating. In fact, it was easily as good as what was being used but cheaper and easier to make.

"There must be a lot of this junk around," Ishmael Hand's report noted. "Consider that my probes were able to discover these three pieces with ease, although none are all that large. Don't try and put them together, though. I doubt if they're from the same device. In fact, I'm nearly positive that they aren't. You see, the coil came from Balshazzar, the gear from Melchior, and the cylinder was sticking out of the purple desert sands on Kaspar."

After all this time, Ishmael Hand could only have faith that anyone was even listening. He had been sent out from a holy world, a retreat and monastic place designed to help you to find what God had in mind for you. One of its orders had trained many of the scouts like Ishmael Hand in the mental disciplines required for such a life, and had carefully prepared them for the long, lonely Communion. Once the Great Silence came about, they had but a few dozen scout ships fully outfitted and not many more candidates than that. They sent half back in the direction of the Arm and Old Earth in hopes of reestablishing contact; the others, like Hand, were sent forward to find the colonies and remap what might be out there. Thus it was that Hand had discovered what had already been discovered, but had also been lost. His broadband, uncoded broadcasts back to every region where there might be listeners were public property. He was not out there for riches or material rewards.

There was enough interest and excitement about the rediscovery of the Three Kings to attract the best and the worst of spacefaring humanity. There was only one problem. While the reporting probe contained the samples and the report and vast amounts of data, nowhere inside could they find star maps or location data or the beacon system that would allow them to get there in a hurry.

This was the fourteenth solar system Ishmael Hand had reported on in the two and a half centuries since he'd launched himself into the unknown, but it was the first and only one where the location data was lacking. It wasn't like Hand to have any such lapses, and he certainly gave no indication in his report that he didn't expect a horde of expeditions to be heading out to the Three Kings straightaway. Nor did any of the data suggest damage or instability in Hand's ship and cybernetic parts. Not even His Holiness in Exile and his monastic group understood what might have caused problems with Hand at this key moment.

And yet nowhere, absolutely nowhere, in any of that data, did it show where the heck the Three Kings were, and at no point was there enough of a star sky given that would allow the position to be deduced.

Hand, as usual for him, wound up his broadcast report with a long string of prayers and chants from the Bible and other holy books, but then he stopped in the middle and added, "You know, if I wasn't sure this was the Three Kings I'd never have named them that. I still considered naming them something else, but there's much to be said for tradition. Nonetheless, beware! The three perfect names I would otherwise have bestowed on these little beauties are Paradiso, Purgatorio, and Inferno. But which was which would only have confused you secular scientists anyway. God be with you when you arrive on these, though, for nobody else will be, and your lack of faith might well be the death of you! Amen!"

And that was the end of the report.

The Three Kings had gone from legend to reality, but were now more maddeningly desired and more maddeningly out of reach than ever.

Still, they had been discovered not once, but twice, even if centuries apart. By hook, by crook, by luck, faith, or perhaps destiny, somebody would discover them again.

Or solve the mystery of Ishmael Hand.

Those in space now divided neatly into two types of people. There was the profane group, the pirates and raiders who made a living from a bit more knowledge of the colonial worlds' positions and assets than most others. And there was the holy group. Not just Ishmael Hand and the Catholic priests and nuns who followed him and his kind, but the others as well, the evangelists and teachers of every conceivable faith who could put together a ship and who were as determined as Ishmael Hand to return the truth of God to the lost colonies.

And finally someone had found a way to the Three Kings, or so he believed. The eccentric former physicist turned iconoclastic evangelist Dr. Karl Woodward had, it was said, discovered the way to Paradise. He had fitted his great ship for a rough ride through a natural wormhole, something considered suicidal for anything save robots and scouts, and he had vanished shortly after. Others tried to follow, lured less by the promise of theological perfection than by the riches of Paradise, but whether any had managed to follow him all the way wasn't known.

What was known was that the route hadn't been left around for others to follow, and nobody, not Woodward or his people, nor anyone who followed, had returned.

The Three Kings of Ishmael Hand seemed as elusive and mythical as ever. . . .