Descartes Before the Whores

Eric Flint

Magdeburg, capital of the United States of Europe

Rathaus, Office of the police chief

October 20, 1636

“I’m sorry, guys, but that’s the way it is. We have to put Descartes before the whores.” Bill Reilly, the city of Magdeburg’s police chief, leaned back in his chair and planted his hands firmly upon his desk, in that ancient gesture of bosses that signified: Here I sit—you can do no other.

Gotthilf Hoch glanced at his partner, Byron Chieske. He decided that this was an issue that had enough of an up-time—what to call it? flavor? aura?—that he could reasonably keep quiet while Chieske handled it. Like Reilly, Byron was an American.

And who but Americans would get this worked up over the fate of a man whom Gotthilf had not only never heard of, but was a foreigner to boot? A foreigner twice over, in fact—born a Frenchman, and still a subject of the French crown, but one who now resided in the Netherlands. And not any of the Catholic parts of the Lowlands, either, like Brabant, even though the foreign fellow in question was himself a Catholic. No, the man had been residing in the Calvinist portions of the Netherlands since he emigrated from France back in…

Gotthilf searched his memory, trying to bring up that item from the briefing they’d just gotten from the police chief.

Back in 1618. Almost twenty years ago now—and the man was only in his early forties.

Typical Catholic, Gotthilf thought disdainfully. This Descartes fellow had apparently left France in order to take advantage of the free-thinking—more free-thinking, at least—attitudes in Holland, but still stubbornly refused to give up his papist heresies.

Not that many of the Lowlands’ Calvinists weren’t also intolerant and narrow-minded, especially the more rabid Gomarists. For that matter, although Gotthilf was a proper Lutheran, there were plenty of Lutherans who suffered from the sin of pride, so certain they were that they knew every jot and tittle of God’s designs for the world. Gotthilf had thought so even before the Ring of Fire and the arrival of the Americans, whose advocacy of freedom of religion had been congenial to him.

But his partner was already protesting, so Gotthilf broke off his ruminations.

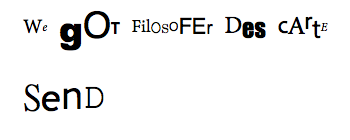

“—no way of knowing if this”—Byron rapped his fingers on one of the sheets atop Reilly’s desk—“so-called ransom note is even legitimate. I mean, for Pete’s sake, Bill, look at the thing. It’s like somebody’s idiot notion of what a ransom note looks like based on watching B-grade cop movies. In the seventeenth century?”

Chieske threw up his hands. “Is kidnapping even a recognized crime in this day and age?”

As sympathetic as he was to his partner’s stance, Gotthilf’s stubborn honesty forced him to state, “Yes, although it’s called ‘abduction.’ But, Byron, whoever’s behind this probably did get the idea—both for the crime itself as well as the ransom note—from watching up-time movies. They’re not all that uncommon anymore, even here in Magdeburg, much less in Grantville—and lots of people make a visit to Grantville these days.”

The police chief grunted his agreement. “He’s right. One of the principal tourist attractions in Grantville are the theaters showing American movies that we had on VHS or DVDs, and even some old Betamax tapes. The last time I was there both the Criterion and the Majestic theaters were running eighteen hours a day—and they were building a new theater complex that was supposed to operate around the clock.”

He leaned forward and tapped his own forefinger on the same sheet of paper that Chieske had rapped with his fingers. “Just like Gotthilf says, that’s probably where the perp or perps got the idea in the first place.”

Scowling, Byron stared down at the sheet. Upon it were pasted letters obviously cut from different sources. Mostly from cheap newspapers, judging by the quality of the cut-out little pieces of paper.

It went on like that: We got filosofer Des Carte send 50,000 dollars or he sleeps with the fishes instructions will follow.

“‘Sleeps with the fishes,’” snorted Chieske. “One thing’s for sure—somebody watched The Godfather.”

He reached back his long arms, planted his hands on the armrests of his chair, and eased himself down. Once seated, he gave the police chief a look that came very close to an outright glare.

“I still don’t see why whatever happened to this Descartes guy is more important than three missing women.”

“For Chrissake, Byron, we’re talking about whores.”

“No, Bill, we’re not. We’re talking about people.”

Not for the first time, Gotthilf was glad that Byron was his partner rather than Reilly. He respected the American police chief’s experience and abilities, but he didn’t much like the man.

Reilly had the grace to look embarrassed for a moment. But it was a brief moment. Within seconds, he was back to scowling. “My point wasn’t that whores aren’t people—which you know damn good and well—but that whores disappear all the time for a hundred reasons.”

He slumped a little in his chair and shook his head. “Look, I got no choice,” he said. He pointed to the ceiling above him with his forefinger. “I got pressure coming down—big time—from on high.”

“From who?” Byron asked.

“The princess.”

“Kristina? What does she care?—and, anyway, she’s only nine years old. How much clout can she have?”

Reilly’s scowl deepened. “Which part of the word ‘princess’ are you having the most trouble with, Byron? How about the phrases ‘sole heir to the throne’ and ‘future empress of the USE’? Those give you trouble too?”

He slapped the desk with the palm of his hand. “Look—it’s settled. Descartes before the whores.” He lifted the hand and made a shooing gesture with it. “So off you go. See if you can find out who’s got him and where they’re holding him. I don’t think we’re dealing with mastermind arch-criminals, here. This is more likely the work of Elmer Fudd than Fu Manchu.”

Gotthilf didn’t understand the specific American references that Reilly was using, but the gist of it was clear enough. He thought the police chief was probably right, too.

Chieske rose. “You’ll let us know when those ‘instructions’ come in, I assume.”

Reilly nodded. Fifteen seconds later, Gotthilf and Byron were moving down the corridor outside, headed for the entrance to the municipal building.

Magdeburg, capital of the United States of Europe

Royal Palace

October 20, 1636

“I killed him, Caroline! The encyclopedia says so!”

Caroline Platzer glanced at the window of Princess Kristina’s room in the royal palace. (Bill Reilly’s finger-pointing at the ceiling of his office had been purely symbolic. Magdeburg’s municipal building was several blocks away from the royal palace.)

Perhaps fortunately, the room had no view of the Elbe. By this point, Caroline was ready to dunk her charge in the river.

She wouldn’t actually drown Kristina, of course. Just…give her a good soaking. The child could be a burden, sometimes.

“You did not kill René Descartes,” Caroline said firmly. “He died of pneumonia.”

“It was my fault! I made him attend me early in the morning—in Sweden! Where it gets cold in the winter. Don’t tell me I didn’t, Caroline! It’s in the encyclopedia! I can read, you know. Four languages! Almost five, now.”

The princess wasn’t boasting. The girl was almost frighteningly precocious.

“For pity’s sake, Kristina, that all happened decades from now—and in another universe. You haven’t done anything to Descartes in this one.”

Kristina’s expression was mulish. “Well…maybe not. But I still feel responsible for him. And now he’s been abducted! Right here in Magdeburg! We have to do something! Like I said to the police chief!”

And hadn’t Bill Reilly been thrilled to get that royal attention, thought Caroline. She didn’t particularly care for the police chief, but at the moment he had her sympathy.

Kristina had been in an agitated mood for weeks now, ever since her betrothed had left to join her father fighting the Ottomans besieging Linz. She’d become very attached to Ulrik and emotionally dependent on the Danish prince she’d be marrying in a few years.

Well, more than a few. It’d be seven or eight years before she was old enough to have a wedding.

“We have to do something!” Kristina repeated. She charged for the door leading—eventually; the palace was large and, in places, labyrinthine—to the street.

Caroline followed, not quite running. Thinking thoughts of princesses tossed into rivers.

Magdeburg, capital of the United States of Europe

Ratskeller

October 20, 1636

“I insist!” said Elisabeth von Schwarzenfels, waving a chapbook under Byron Chieske’s nose. “I must bring Descartes before the Horus!”

The American policeman looked up at her, frowning. “Before the…what?”

“The Horus! The eye of Horus!” Von Schwarzenfels rotated the chapbook in her left hand so that Chieske could see the cover. With the forefinger of the other hand, she imperiously jabbed at the illustration across the top. It was an eye of Horus…sort of. Allowing for the pronounced suggestion that this particular Horus was a Peeping Tom.

Byron groaned. Not at the illustration but at the sight of the chapbook’s title.

THE NATIONAL OBSERVER

Enquiring minds want to know!

“Oh, for God’s sake,” he said, lapsing into the blasphemy that he usually avoided in deference to seventeenth-century mores. “That rag.”

“It’s a matter of freedom of the press!” said the young woman.

Elisabeth von Schwarzenfels was dressed in a satin-tabbed bodice with full sleeves, dyed gold and lavender and trimmed with silver braid, along with a matching petticoat. Her bodice was laced up with a coral ribbon over a stomacher, with a matching ribbon set in a V-shape at her front waist and tied in a bow to one side. A ribbon and a string of pearls decorated her auburn hair.

In short, she had the appearance of exactly what she was—a member of the German upper nobility, the Hochadel, but one whose family was not especially wealthy. The clothing was well-designed and well-made, but not extraordinarily expensive.

Gotthilf busied himself with quaffing from his stein of beer. He was seated on the other side of the table from his partner. After finishing their discussion with Reilly, the two of them had repaired to the tavern in the basement of the city hall to discuss the case of Descartes in a more congenial setting. Von Schwarzenfels had tracked them down there less than forty-five minutes after they’d left the police chief’s office. How she’d managed to do that was a mystery to Gotthilf.

Perhaps an even bigger mystery to the level-headed policeman was the woman’s evident devotion to a profession that would seem quite unsuitable to such a one as she. Not only had Elisabeth von Schwarzenfels chosen to become a journalist, but one who devoted most of her time to writing for a magazine which, in the short time since it had been launched, had already become disreputable. The National Observer was what the up-timers called a “scandal sheet” or just the pithier term “rag” that his partner had used.

“Freedom of the press!” Elisabeth repeated. “I insist on reporting on your progress in apprehending the scoundrels who abducted one of Europe’s most famous philosophers.”

Gotthilf laughed and gestured to an empty chair. “Litsa, have a seat and join us for a beer. I’m getting a crick in my neck from looking up at you. And stop pretending. You never heard of Descartes any more than we did—until he got taken a short time ago. He’s not famous now.”

Von Schwarzenfels looked stubborn. “Well, he will be famous, Gotthilf. I know! I asked Melissa Mailey. She said this Descartes fellow will be—already was, in the world she came from—one of the most famous thinkers of all time.”

Chieske looked over at his partner. Hoch shrugged. “I’ve known Litsa for a while, Byron. If we don’t let her come along, she’ll just follow us and be an even bigger nuisance.”

Privately, although he wasn’t about to say it out loud, Gotthilf thought Litsa might even be of help to them. He’d been on friendly terms with the young noblewoman since she got back to Magdeburg from a recent adventure. One thing he’d learned about her was that when she got interested in a subject she would pursue it indefatigably—and she seemed to have a genuine knack for getting information out of people. The articles she wrote for The National Observer had quite a bit of real substance to them.

Her prose was terrible, though. Really, really terrible.

Magdeburg, capital of the United States of Europe

Rathaus, police headquarters

October 21, 1636

“Descartes before the—” Hoarse from her overly long and passionate peroration to Magdeburg’s mayor Otto Gericke on the necessity to save one of history’s greatest philosophers, Melissa Mailey broke off from her current—equally passionate if not (yet) as overly long—peroration to the two policemen who’d been assigned to the case.

Cough, cough. “Sorry,” she said. “Before the publication of his Discourse on the Method—that happened in the year 1637, in the universe I came from—Descartes was an obscure figure to most people. So it’s not at all surprising that neither of you had heard of him. In this universe…”

She frowned, searching her memory for what she remembered about Descartes—most of which came from her perusal of the encyclopedias in Magdeburg’s city library that morning. The course she’d taken on the history of philosophy in college was a long ways back.

“I’m not sure what’ll happen in this universe.” She gave Byron Chieske and Gotthilf Hoch a stern look. “Assuming that Descartes isn’t just murdered outright, as his kidnappers are threatening to do.”

“We’ll do our best to prevent that,” said Byron. He was trying to be reassuring, but to Melissa he just sounded stolid.

She sighed and ran fingers through her hair. It was completely gray now—and a dull and dismal shade of gray at that, to her mind. That caused Melissa some never-admitted-aloud but genuine distress. The discreet and demure up-time hair-coloring she’d used since her mid-forties and for a while after the Ring of Fire had all vanished some time ago. And Melissa simply didn’t have the temperament to use the more garish types of hair-coloring available in the seventeenth century.

“Anyway,” she continued, “the main thing he’d been working on was a work called Treatise on the World, but he hid that away after Galileo was condemned because he’d pretty much supported Galileo’s astronomical views.”

Gotthilf frowned. “But Galileo wasn’t—”

“Wasn’t condemned,” Melissa finished for him. “No, he wasn’t—in this universe. That’s mostly because of Larry Mazzare,” she added, with a great deal of home-town pride. “So, who knows? He might wind up publishing Treatise on the World, after all.”

The stern look returned. “Assuming you manage to keep him from being killed.”

“We’ll do our best,” said Byron stolidly.

* * *

Once Melissa had left, Byron shook his head. “I’d still rather be looking for those missing girls. This case…” He shook his head again. “I got no idea where to even start.”

Elisabeth von Schwarzenfels, who’d charged off the afternoon of the day before after receiving a tip, came charging into the office where Byron and Gotthilf had invited Melissa Mailey to provide them with some background.

“Someone saw him!” she exclaimed. She was practically bouncing with excitement. “Just two days ago! Descartes before the Horace!”

“The Horace?” Gotthilf and Byron glanced at each other.

“What would a philosopher be doing in that dive?” Chieske wondered.

Gotthilf shrugged. “Maybe he’s fond of bad music and worse women.”

“Or was looking for chewing tobacco,” Byron said, followed by a snort of derision. The Horace was a tavern to the west of Magdeburg’s Neustadt, about a mile from the Navy Yard. The owner fancied a décor that included imitations of up-time mementos, one of the most prominent of which was a “Mail Pouch” advertisement next to the entrance.

“You will never find a more wretched hive of scum and villainy,” said Elisabeth.

Chieske rolled his eyes. “Give me a break.”

“I like that movie,” protested Elisabeth.

Magdeburg, capital of the United States of Europe

Inside Horace Tavern, Greater Magdeburg

October 21, 1636

Elisabeth looked around the central room of the tavern, scrutinizing the patrons. At this time of the day, there were only four of them. All three who were awake were clearly inebriated. Presumably, the man who was slumped back in his chair, his eyes closed and snoring, was drunk also.

“These are not the philosophers we’re looking for,” she pronounced.

Byron grimaced. Gotthilf smiled. He’d been quite taken by the Star Wars film himself, enough to have watched it twice.

The tavern keeper behind the counter along one side of the room—what up-timers would have called “the bar”—just looked puzzled. The man wasn’t the owner of the establishment, just an employee, and from what Gotthilf had been able to determine he seemed not much better informed of the world around him than the yeast in the beer he served.

“When is Eberhart going to return, then?” asked Chieske. He’d given up trying to discover the owner’s whereabouts, since the tavern keeper’s only response to that question—which the up-time policeman had now asked three times—was a sullen shrug.

The tavern keeper shrugged again. Sullenly.

Gotthilf continued his examination of the Horace’s interior décor. This was the fourth—no, fifth—time he’d come into the establishment and he was looking for anything that might have changed since the last time he was here. There was no particular reason for doing so; he was just trying to pass the time while his partner continued his fruitless interrogation of the man behind the counter.

Next to the entrance was the Mail Pouch advertisement that had been there the first time Gotthilf had entered the Horace. That had been…eight months ago?

Somewhere around that time. To the right of that was an octagonal up-time stop sign, whose red color was starting to fade or—more likely—was a down-time replica that had never been a bright red to begin with.

To the right of the sign was an up-time television set, perched on a ledge. Gotthilf had no doubt that was genuine, since no one would have bothered to make an imitation TV set that was obviously old, decrepit and non-functioning.

The rest of the décor on the wall behind the counter was of no great note. Neither was the billiards table nearby, which was down-time made but of the American “pool” design.

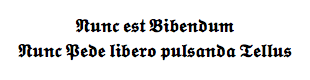

More interesting was the large sign hanging on the wall facing the entrance. In Fraktur script, it read:

The Latin translated roughly as “Now we must drink, and stamp the ground with a free foot.” It was a quote from one of the Odes of the ancient Roman poet Horace, after whom the tavern was named.

How the tavern’s owner Konrad Eberhart, who knew no Latin and had never been known to set foot inside a church of any denomination since his arrival in Magdeburg, had come across those Odes was a mystery. As was, for that matter, everything else about the man. Gotthilf thought the likelihood that “Konrad Eberhart” was his real name was about the same as the likelihood that he was a former ballet dancer. Which, given his stubby legs and impressive girth, Gotthilf placed somewhere between “fat chance” and “hell freezes over.”

Gotthilf tried to think of any reason a philosopher would have come to such an establishment. Besides alcoholic beverages of poor quality and the company of prostitutes who were no better, he couldn’t think of any. Either this Descartes fellow was very short of funds or he just had a taste for lowlife—what his up-time partner sometimes called “slumming.”

Neither seemed very likely to Gotthilf, especially the first reason. A man who could support himself without doing any visible labor wouldn’t presumably be so short of money that he’d have to make do with the entertainment available at the Horace.

On the other hand, what did Gotthilf Hoch know about philosophers? Being honest, not much of anything.

“Let’s go,” said Byron, who’d finally given up trying to get any useful information from the bartender.

* * *

When he advanced his two (very tentative) hypotheses to Chieske, after they’d left the tavern, the American policeman shook his head.

“I think it’s probably even simpler than that. We still haven’t found out where Descartes was staying.”

“The Horace doesn’t have any rooms to let,” protested Gotthilf. “At least, I saw no sign of any.”

“Neither did I. But he might have been staying in the vicinity and just happened to be walking by the Horace when Litsa’s informant spotted him.”

Gotthilf came to an abrupt halt and slapped his forehead. “Ah! Stupid! Of course—I assumed he was going into the place. But he could have just been passing in front of it.”

He looked around. This part of Greater Magdeburg wasn’t a slum, but that was mostly because like almost all parts of the city the construction was too new to have started decaying. Still, it was several steps down from the sort of neighborhood Gotthilf would have expected to find one of the world’s greatest minds choosing to reside in.

Byron, who’d also come to a halt, gave a little shrug. “Who knows?” He started walking toward the Rathaus again. “Let’s see if we can track down Melissa. She might know something she doesn’t even realize she knows.”

* * *

Indeed, so it proved.

“Interesting,” she mused. “One thing I learned from the study I just did of what information we have on Descartes is that he was an odd duck in all sorts of ways. One of them is—a philosopher! Go figure!—he never owned very many books. Apparently he didn’t like to read much. Another is that he moved constantly. From town to town, and from lodging to lodging. So it’s quite possible that he’d taken a room somewhere in the vicinity of the Horace. And there’s one other thing!”

Triumphantly: “I’m pretty sure I know why Descartes came to Magdeburg in the first place. That was another unsolved mystery, wasn’t it?”

Gotthilf wouldn’t have labeled that question a “mystery,” himself. After all, lots of people came to Magdeburg every day for all sorts of reasons. Still, it was true that they hadn’t yet uncovered Descartes’ reason.

“Somebody with his description went to the hospital three days ago and tried to get an interview with James.”

Byron looked puzzled. “With Dr. Nichols? Why? Did the guy say he was sick? And did your husband agree to see him?”

Gotthilf had to struggle not to laugh, seeing the prim and disapproving expression on Melissa’s face. In point of fact, she and Dr. James Nichols were not married, although they had been living together and enjoying conjugal relations almost since the Ring of Fire. Apparently—no down-timer could ever make any sense of it—Mailey found a source of pride in the fact that she and Nichols were flouting convention.

There was a witty little saying that had spread widely in the years since the Ring of Fire: All Americans are weird some of the time, and some Americans are weird all of the time. Melissa, if not her paramour, was generally considered to be pretty far over to the weird-all-of-the-time end of that spectrum, at least by those who found her political and social views rather abhorrent.

Melissa shook her head. “James didn’t see him for the simple reason that he’s not in town. He went to Dresden for a few days, to help them set up the operation of their new hospital. But I’m willing to bet the reason Descartes wanted to see him wasn’t because Descartes himself was feeling ill. I checked with the people who saw the fellow and they said he didn’t seem sick.”

“So why’d he want to see Dr. Nichols?” asked Byron.

“I think it was because Descartes must have read a biography of himself somewhere and learned that his daughter Francine is—well, she’s not sick now. But in the universe we came from, she died—would die, will die; you parse the grammar any way you want—about four years from now. The girl is a year old. She’s ‘scheduled’ to die in 1640, from scarlet fever. Of course, that’ll never happen because of the butterfly effect. But who’s to say she won’t die even earlier, from some other disease? Child mortality’s horrible in this day and age. Still is, even with the medical knowledge we up-timers brought with us.”

Byron grunted. “So. You’re saying Descartes showed up here in Magdeburg hoping…for what, exactly? If his daughter’s not sick yet, what’s Dr. Nichols supposed to do?”

Melissa shrugged. “I imagine Descartes wanted James to agree to treat his daughter if and when she does get sick—which she’s almost bound to, these days. Especially if she’s not living in Magdeburg or Grantville or someplace that has a decent sewage system. Which, so far as I know, is not true of any city or town in the Netherlands outside of maybe the royal palace in Brussels.”

The stern look of almost-reproof came back. “Presumably, that’s still what Descartes wants—if he hasn’t been murdered yet.”

“We’re doing our best, Ms. Mailey,” Chieske said stolidly.

Magdeburg, capital of the United States of Europe

Rathaus, police headquarters

October 22, 1636

The young man who was escorted into the office shared by Gotthilf and Byron looked to be in his early twenties. From various subtleties in his dress and demeanor he was clearly a down-timer, although he had an expensive-looking up-time camera suspended around his neck by a strap.

“Yes?” asked Byron. “What can we do for you?”

“And what’s your name?” added Gotthilf. The man looked familiar to him, but he couldn’t remember when and where he might have encountered him.

The youngster looked uncertain. “Well, I’m here because…ah, I’m Anton Fuchs.”

The name refreshed Gotthilf’s memory. “Ah, yes,” he said. “You work with Litsa sometimes. For The National Observer.”

“For Simplicissimus too,” Fuchs said, naming the other magazine Elisabeth von Schwarzenfels wrote for. He tapped the camera hanging from his neck. “I’m the freelance photographer Litsa usually hires when she needs one.”

“So what pictures is she having you take now?” That came from Byron, who didn’t sound particularly interested.

Fuchs shook his head. “No, it was something else, this time. She told me she was planning to return to that tavern she visited with you yesterday. The Horse, I think it was.”

“The Horace,” Gotthilf corrected him. “Whatever for? And when was this?”

“She said she thought there was something suspicious about the place. And it was last night. She said she wanted to wait until it was dark so the barkeep wouldn’t recognize her if he was still there when she went back. She also said she was planning to disguise herself as a whore.”

“Oh, for God’s sake!” exclaimed Byron, once again forgetting to avoid blasphemy.

Years of Lutheran discipline kept Gotthilf from blaspheming himself, but he had no trouble understanding his partner’s exasperation.

Elisabeth von Schwarzenfels? “Disguised” as a whore?

The notion was preposterous. The young noblewoman had absolutely no idea how a prostitute of that station in life would speak or act. Gotthilf doubted if she could pull off being disguised as a high-class courtesan, for that matter. She had the wrong personality, to put it mildly—and Gotthilf had never seen the slightest indication that Litsa could behave in any other manner than the one that came to her naturally. Which could be summed up in the word…

Brash? Impetuous? Headstrong? All of them would do.

“Reckless,” muttered Chieske.

Yes, that word too. Gotthilf rose to his feet. “So why are you here?” he asked Fuchs. “I presume she hired you to serve as her watchdog.”

The young photographer nodded, looking very worried now. “Yes. She said if she hadn’t returned in the morning I should come here and tell you.”

Gotthilf and Byron exchanged glances. For a moment, Chieske looked utterly exasperated. But he, too, rose to his feet—and took his Colt .45 pistol out of the desk drawer where he kept it when he was working in the office.

Gotthilf touched the holster at his own hip, reflexively making sure that his own weapon was there. That was done purely out of now-ingrained habit, though. The down-time-made H&K .44 seven-shot revolver that he favored was quite heavy—heavy enough that he could sense its presence even sitting down.

“Let’s go,” Byron said grimly. “Let’s just hope the silly girl hasn’t gotten herself in a real bind.”

He and Gotthilf headed for the street entrance, with Fuchs trailing behind. Gotthilf thought about ordering the photographer to stay behind, since he had no weapon other than his camera. But…who could say? He might prove to be of some use.

Magdeburg, capital of the United States of Europe

The Horace, a tavern in Greater Magdeburg

October 22, 1636

Seeing no reason to dally, the two policemen charged into the Horace as soon as they arrived. Gotthilf went first, with his revolver drawn and in his hand.

Quickly, he glanced around to see if there was any kind of threat visible.

Nothing. The barkeeper from the day before was nowhere to be seen. The only people in the tavern this early in the morning—the sun had risen some time earlier, but they were still closer to dawn than noon—were a drunk collapsed over a table and a would-be troubadour leaning against the bar plucking away at a double-necked lute. A woman perched on the bar had her arms around him and was exclaiming some sort of appreciative noises.

No one else was to be seen. Gotthilf started to relax until his eyes returned to the woman sitting on the bar. She was fairly young and fairly attractive, but what really registered on him—nagged at him, rather—was that…

What was it about her?

Of course. She fit the description of one of the prostitutes who had gone missing earlier that week.

As Gotthilf grappled with that thought, trying to figure out what if anything it might signify, two other phenomena made their appearance.

First, the bartender—the same man they’d already encountered—came into the main room of the Horace through a door so narrow that Gotthilf had presumed it to be the entrance to a broom closet the day before.

But, apparently not, because a light was shining up from somewhere below. That narrow door must lead to a cellar of some sort.

A moment later, the second phenomenon made its presence apparent.

That was a woman’s voice coming through the same open door. Litsa’s voice, to be precise—which was quite a distinctive one. And while Gotthilf couldn’t make out the words she was yelling, they clearly expressed such sentiments as…

Outrage. Indignation. Displeasure.

“That’s Litsa!” exclaimed Byron. “She sounds scared!”

Yes, that word too.

The young woman squawked with fear and threw herself off the bar so violently that she sent the troubadour-not-ready-for-prime-time sprawling on the floor. She then raced for a door in a corner on the wall opposite the entrance the two policemen had come through, flung it open, and ran into what appeared to be an alley beyond.

The barkeeper issued a squawk of his own and ran after her.

Out of reflex, Gotthilf almost chased them, but there was still Von Schwarzenfels to look after. So, he ran toward the narrow door leading down to the cellar, his pistol still in hand.

The guilty would just have to flee where no man pursued. Perhaps they could track down the prostitute and the bartender later.

He had to jump over the prone body of the lute-player to get to the door. Judging from the noises behind him, Byron had tried make the same leap and failed. It sounded as if Gotthilf’s tall up-time partner had sprawled across the tavern floor himself.

But Hoch had no time to worry about that now. He was through the door and pounding down a set of equally narrow stairs. The risers were pitched so steeply that he had to concentrate entirely on not falling.

Only when he reached the bottom was he able to look around.

He was in a cellar, sure enough. Two lamps provided a surprising amount of light. Gotthilf didn’t take the time to check, but he assumed they were the new up-time-designed lamps called “Coleman.”

The key thing was that he could see quite clearly.

There were five other people in the cellar. In the far corner was a man he didn’t know, with a big nose and long dark hair. That matched the description of Descartes. Standing next to him, with a knife held to the big-nosed, dark-haired man’s throat, was a fellow Gotthilf recognized as the Horace’s owner. That was the man who called himself Konrad Eberhart. He was just as stubby-legged and paunchy as Gotthilf remembered.

Since Eberhart was only armed with a knife rather than a gun, Gotthilf took the time to glance into another corner of the cellar.

Litsa was there. Two women were holding her by the arms. At a guess, going by the descriptions he and Byron had gotten, those were the other two missing prostitutes.

They seemed to pose no immediate danger, however, so Gotthilf’s eyes went back to Eberhart and the man he presumed to be the missing philosopher.

The tavern’s owner immediately confirmed his presumption.

“Drop the gun or Descartes gets it!” shouted Eberhart. Either from intent or nervousness—most likely the latter—he jiggled the knife hard enough to open a gash in the philosopher’s neck.

It was a very shallow wound, not in the least bit fatal and not even one that bled badly. But it was enough to make Descartes gasp.

It was also enough to make up Gotthilf’s mind. As agitated as he so clearly was, Eberhart was just as likely to kill his victim by accident as by design.

Nothing for it, then—and at this range, Gotthilf was quite a good shot.

He took the proper stance, aimed the revolver between Descartes’ legs, and fired.

In the cramped, enclosed space, the noise was deafening. More than loud enough to drown out Descartes’ cry of fear and Eberhart’s shriek of pain.

Which would turn to agony, once the shock wore off. The heavy .44 bullet had passed between the philosopher’s spread-apart legs and struck Eberhart’s left knee. The poor bastard would be a cripple the rest of his life—which might be a short one, depending on how Magdeburg’s judiciary gauged the severity of the newfangled crime of “kidnapping.”

That one shot had ended the standoff, though. Eberhart had collapsed, flinging the knife away somewhere. He was now only half-conscious.

Gotthilf turned to the three women. Casually, he waggled his revolver back and forth a couple of times.

“Do I need to keep shooting?” he asked.

Hastily, the two women holding Litsa let her go. She shook her arms, took a step forward, and then suddenly spun around and struck one of the women on the face hard enough to knock her down.

The other woman backed up, but Litsa didn’t do more than scowl at her.

Moving toward Gotthilf, Litsa pointed behind her to the woman she’d struck. “That one’s name is Gisela. The other one’s Cloris. They’re two of the missing prostitutes you were worried about—ha! And for no reason! They’re nothing but criminals themselves. Kidnapperesses. They’re the ones who Eberhart hired to guard Descartes.”

She looked up at the stairs to the tavern above. Byron was starting to come down them now. “There’s a third one, too,” Litsa went on. “I think her name’s Brenda but I’m not sure. She was here last night but I don’t know where she is now.”

The one named Gisela started to rise. Seeing that, Litsa hissed, strode over, and gave her a kick to the ribs.

Gisela went down again, clutching her side.

“How’s it feel, you bitch?” shrilled Litsa. Turning back to Gotthilf, Litsa said angrily, “She kicked me! Three times!”

She then glared at Cloris, who was by now backed against the wall. “And that one hit me!” But she didn’t do anything more than glare.

Byron reached the cellar floor. “Sorry,” he said to Gotthilf. “I fell.” He looked around. “But you seem to have handled everything fine.”

He looked at Descartes, who was ashen-faced but otherwise seemed in good health.

“You’re the philosopher, right? Are you okay?”

Descartes just stared at him. So busy cogitating over the fact that he still existed that he was at a momentary loss for words, Gotthilf presumed.

Magdeburg, capital of the United States of Europe

Home of Melissa Mailey and James Nichols

October 25, 1636

James Nichols handed Melissa one of the two cups of coffee he’d just made. War with the Ottoman Empire and disruption of trade routes be damned. As the premier doctor of Europe—probably the whole world, in fact—Nichols was rich enough to afford as much coffee as he and his not-exactly-a-wife wanted.

His conjugal duties of the morning fulfilled, James resumed his place alongside Melissa in their bed. He had the subtly self-satisfied expression of a man who’s spent the night before fulfilling other conjugal duties. Melissa would have teased him about it, but, truth to tell, she was feeling pretty self-satisfied herself. It had been a nice reunion.

Even if James had been gone for less than a week. He’d just returned to Magdeburg the night before.

“So how’d it finally settle out?” he asked her. Melissa had only given him a brief sketch the night before of what she had taken to calling l’affaire Descartes.

“Well, first off, you’ve got a new patient. Three of ’em, in fact.”

Blowing on his coffee to cool it down, Nichols frowned. The expression signified puzzlement, not protest. “Three…There’s the girl—what’s her name? Francine?—and Descartes himself, I assume. Who’s the third one?”

Well, no. That’s what we thought. But it turns out we did the same thing that we make fun of down-timers for all the time. We assumed that history didn’t change at the Ring of Fire.”

James made a face. “What do you mean? I thought he was ‘having his way’ with the servants in Amsterdam.” The casual readiness of seventeenth-century men of means to take sexual advantage of their servants was something up-timers disapproved of strongly—even if plenty of American men had been (and still were) guilty of sexual harassment themselves.

Seeing the expression, Melissa shook her head. “It’s a little more complicated, in this case, from what I read about Descartes. In the original history, apparently he took care of the woman for years, even after the child died of scarlet fever. But the key is the tryst with the servant happened after we arrived. So it didn’t. We assumed it did. Butterflies bite the smarty-pants up-timers in the ass.”

James blew on the coffee again. “Fine. René Descartes is a paragon of virtue, at least by seventeenth-century standards. And he didn’t diddle the serving girl. So who are my three patients?”

Melissa pulled her knees up to her chin and patted the bed beside her. “It turns out that Descartes was way ahead of us. He has been living in Paris, got married, and caused enough trouble to get practically assassinated and driven into seclusion since the Ring of Fire.”

James sat on the edge of the bed. “Busy guy. But who are the patients?”

“Basically the same, with the addition of Descartes himself. He was actually rather badly injured in an assassination attempt, and he has some tendon damage in his hand. But he still has a wife and daughter. So he is worried about the same scarlet fever thing happening again. Or some other disease.”

“What else came out of the dickering? And who did the negotiations, anyway? I can’t imagine Kristina making more than a complete mess of it.”

“Who do you think? Caroline Platzer, of course. She got Descartes to agree to Kristina’s desire—okay, let’s be honest and call it a petulant royal demand—that Descartes become one of her tutors. The girl says she’s trying to make amends for—I love this part—the fact that she killed him in another universe, but the truth is I think she just likes the idea of having a famous philosopher as a tutor.”

James chuckled. “He isn’t famous. In this universe, that is.” After a moment, he added, “Yet, anyway.”

Again, he blew on the cup. Unlike Melissa, who’d already started drinking hers, the doctor preferred his coffee almost lukewarm. “But why’d he agree? It can’t just be the medical angle. The truth is that he doesn’t need me to be anything more than an occasional consultant. Possibly some minor surgery, most likely just some physical therapy, depending on his injuries. Which is just as well, since I need to get back to the siege at Linz soon. So do you, for that matter.”

“Well, first off, Caroline pointed out to him all the medical advantages he’d gain if he resettled himself and his daughter—and his wife—here in Magdeburg.”

Melissa set down her cup on the table next to her side of the bed and started counting off her fingers. “First, decent sewage. Second—he really liked this part, since cogito ergo sum can be done sitting on the can as well as anywhere else—decent plumbing. Third, the best hospital in the world.”

“One of ’em, anyway,” James qualified. “In some respects, the ones in Jena and Grantville are just as good or better, and there’s a lot to be said for the new hospital in Bamberg.”

Melissa made a tongue-clucking sound. “Thankfully, Caroline’s a better negotiator than you’ll ever be. According to her version, Magdeburg’s hospital is way better than any other one. And finally—”

She counted off the fourth finger. “Caroline got Kristina to agree—and it’s in writing, not just verbal—that her lessons with Descartes won’t ever start before noon. Oh, yeah, and she also pointed out”—here Melissa counted off the last finger—“that the royal palace here in Magdeburg, quite unlike the one in Sweden, also has decent heating so it doesn’t get cold in the winter. Not enough to induce pneumonia, at any rate.”

“Actually, cold by itself is not really a major factor when it comes to contracting—”

“As I said,” Melissa overrode James’ qualification, “thankfully, Caroline did the negotiating, not you.”

James decided his coffee had cooled off enough, so he took a sip. As he did so, Melissa went on to say: “But, just as you guessed, there’s more to it than just the medical angle. There are also what you might call the political and doctrinal issues.”

Nichols raised an eyebrow. “Meaning…”

“Meaning that Descartes is still a Catholic even if he’s not what you’d call an orthodox one. That’s the reason that he suppressed years of his work in the universe we came from, after the church condemned Galileo.”

“But—”

“The church didn’t condemn Galileo in this universe, thanks largely to the fact that Larry Mazzare defended Galileo at his trial.” Melissa looked very smug, right then. “That would be the same Larry Mazzare, Caroline pointed out to Descartes, who is now the Cardinal-Protector of the USE.”

“Not according to Cardinal Borja,” said James. “And the pope who appointed Larry to that position got murdered a little while ago.”

“Pfah. Descartes’ unorthodoxy stretches plenty far enough that he’s got no use at all for Borja and his pack of thugs. He’s an adherent of the Urbanite faction in the church. And he very much liked the idea of having Mazzare as the one overseeing his work from a doctrinal angle. He’s already started talking to printers about publishing his new work. He builds on all of the philosophy of the last three hundred years, and is supposedly taking it in new directions . He is calling it Le Nouveau Monde.”

She chuckled again.

“What do you find so amusing?”

“To me, the funniest part about the whole thing is the photograph that Kristina insisted on having taken after the negotiations were done. Litsa’s freelancer photographer did it, and Kristina’s planning to have it framed and hung up in the palace. Fuchs is really a good photographer, I’m told, and I figure that framed photo is bound to wind up eventually on the wall of a museum somewhere.”

“You’re probably right. But so what?”

Melissa grinned. “The picture shows Kristina perched atop her favorite horse with Descartes—looking none too pleased about it, let me tell you—standing in front of the critter and holding the reins.”

“I still don’t—oh.” James grinned also.

“Exactly. I’m sure Kristina’s planning to title it something like ‘The Princess and the Philosopher.’ And that’ll stick, in German or Amideutsch. But in English?”

James laughed out loud. “It’ll be Descartes Before the Horse. What else?”