The Game of War

Written by Robert E. Waters

"Strategy without tactics is the slowest route to victory. Tactics without strategy is the noise before defeat."

—Sun Tzu

April 1635, somewhere near Zernez, Lower Engadin, Switzerland . . .

Klaus Gremminger stared into the lifeless eyes of General Herman Dettwiler and imagined victory. The arrogant, brash, but well-respected leader of von Allmen's small army was lying dead in his own tent, caught unawares and overrun. Gremminger smiled as he placed his hand over the man's eyes, closed them, and made the sign of the cross. Dettwiler was a Protestant, but he deserved at least a modicum of respect. He'd fought bravely, dogging Gremminger's men from one Alpine pass to the next, and his defense of the narrow road leading to Davos had been more than admirable. But now here he was, in a pool of his own blood, his leg severed by an old French cannon and the left side of his body scarred with saber slashes. It's mine, Gremminger said to himself, making the sign of the cross again. The Flüelapass is mine.

Gremminger turned quickly and pointed a long, sharp finger at a youth standing beside the flap of the tent. "Get the men ready, Amon. We're going to follow those bastards all the way to Davos."

The expression on the boy's face left a cold sting in Gremminger's heart. So too did the cool air flowing into the tent. He winced. It had been mild just this morning, but something had changed. "What is it?"

The boy swallowed and said, "Sir, Captain Galli reports that snow is falling on the Wisshorn and that soon it will be upon us here." He swallowed again, apparently unsure of how to continue. "We cannot pursue in this weather . . . so he says, sir."

Gremminger slammed a fist onto the table where Dettwiler lay, jarring the dead man and jostling his head left to right. He pulled his hand back. Was he still alive? How silly. The general was dead and that was that. Moving his head in such a fashion was nothing more than force upon the table. It was not a response to what Amon had said, nor was Dettwiler mocking him from the afterlife. More likely, Gremminger concluded, Dettwiler's soul was on its way to Hell, where it would rot with the rest of von Allmen's men who had suffered a similar fate during the ambush. And they deserved nothing less than eternal pain for throwing their support behind the Zehngerichtebund, the League of the Ten Jurisdictions, despite the fact that von Allmen's lands and holdings lay within the borders of the Gotteshausbund, the League of God's House.

Traitors!

And now with those devil Americans, who had literally fallen out of the sky in an event being called the Ring of Fire, the Zehngerichtebund and its capital Davos was growing more powerful by the day. They had not officially thrown their support behind the Americans and the USE, but Gremminger knew it was just a matter of time. Gregor von Allmen had, on many occasions, publicly denounced the Hapsburgs, the League of Ostend, and their campaign against the Swedish king and his up-time wizard allies. What was going on inside Germany had not trickled down into Switzerland, into the Grisons, but it was coming. The winds of change were blowing, and it was not a cold, bitter wind like the one ruffling the flap of the tent. It was a wind hot with war, sorrow, blood and smoke.

A courier burst into the tent and stood at attention, a dusting of snow melting on his dark wool coat. The light-haired boy caught his breath and held out a scrap of paper. "A note from Tarasp, My Lord."

Gremminger took it and read it quietly. It was a short note, scribbled hastily with a rich man's quill. Gremminger read it again, and again, and the cold spot in his heart warmed. He was surprised at what the note contained, surprised at who had written it. Then again, the political and military situation in Tarasp, in Austria, and even in Tyrol was infinitely uncertain these days. Competing Hapsburg interests lay everywhere. Who was a friend, a foe? Who knew? He looked at the note again. He was surprised, but pleasantly so. "Do we know yet who has taken command of Dettwiler's men?"

The two boys shook their heads. Amon spoke. "No, sir, not for certain, but we suspect Captain von Allmen. He was the general's personal assistant."

"Thomas von Allmen? Gregor's runt?"

The boy nodded.

Gremminger huffed. "This gets better and better."

He turned back to Dettwiler and smiled into the pale, stiffening face. He read the note again. "All right, Amon," he said. "Spread the word: We'll set camp here and wait out this snow. And then, in a few weeks when the passes reopen, we'll face von Allmen . . . and bleed his army to death."

The boys left the tent. Gremminger looked at Dettwiler's face again, making sure his eyes were closed. They were. Thank God for that.

He read the note again. He loved the words. They were like poetry, verse for the heart. Four little words, initialed by a captain.

The Spanish are coming.

LM

****

Thomas von Allmen dreamed of Vietnam. It was a recurring dream and one that he had begun having after his return from Grantville. It was a war that had not yet occurred in his time, in a place a world away, dealing with strange, exotic people he had never seen. Yet the dream was always there: the places where Americans and Viet Cong clashed in dense, lush jungles and where bombers rolled like thunder, dropping napalm to scorch the ground in hellfire. The Battle of Bong Son. The Battle of An Lao. The Tet Offensive. Ripcord. Saigon. Men clashing with weapons and materiel only magic could conceive. It was a waste of time for him to lose precious sleep on such a dream when there were far more pertinent ones he might be having. The American Revolution. The Napoleonic Wars. Even the American Civil War was more appropriate to his situation. But perhaps that was why he dreamed of Vietnam, for it took his mind off the reality of his world, his situation. Here he lay dreaming, slumped over a hastily constructed table, covered in cartography roughed out over hexagon paper, cluttered with tiny wooden blocks sporting NATO symbols carved into them like the initials of lovers on a spring tree. He was a member of Charlie Company, Third Platoon, dressed in jungle camouflage. He stepped through the thick underbrush in the humidity of a hot Asian night, caught his boot on a trip-wire, and screamed as his body ripped apart.

He awoke and the white dice clasped in his hand tumbled to the ground. He was not as sweaty as he usually was after such a dream, but perhaps that was because the flap on his tent was open and cool air swept in. It was getting warmer, and the late snows were melting away, but up here among Alpine rock, with the Silvretta Range in view, a cool breeze was a welcome change from the bitter wind that had plagued his disgruntled army.

My army.

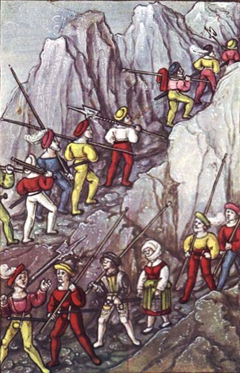

The truth of it was just as strange now as it had been when he took command three weeks ago, after General Dettwiler's bitter and untimely death. Despite the odds against it, he had managed to rally the general's routing men and put them into a defensive position around a small village just ten miles east of Davos. Von Allmen shook his head at the memory and scooped up the loose dice. Routing Swiss. It was almost a contradiction in terms, as the Swiss had been known for centuries to be the toughest and most stalwart soldiers on any battlefield. They simply did not retreat, did not give ground or quarter. Swiss mercenaries were the prize possession of any European army, and his men had diminished that reputation.

The truth of it was just as strange now as it had been when he took command three weeks ago, after General Dettwiler's bitter and untimely death. Despite the odds against it, he had managed to rally the general's routing men and put them into a defensive position around a small village just ten miles east of Davos. Von Allmen shook his head at the memory and scooped up the loose dice. Routing Swiss. It was almost a contradiction in terms, as the Swiss had been known for centuries to be the toughest and most stalwart soldiers on any battlefield. They simply did not retreat, did not give ground or quarter. Swiss mercenaries were the prize possession of any European army, and his men had diminished that reputation.

But he could not blame the men. It wasn't their fault. They weren't to blame for Dettwiler's blunder. Von Allmen had warned his commanding officer about where he had deployed the army, had told him that Gremminger's troops, especially his cavalry, could make the distance from Zernez quicker than he realized. "How do you know such things?" the general had asked. Thomas' simple reply was, "Because I've played it out."

That was the wrong choice of words, Thomas realized now, but it had been too late to fix the error. An hour later, their surprised army was falling back onto itself, desperate to find protection from Gremminger's men who had outflanked a forward advance of fifty pike with flailing sabers, relentless hooves, and snaphaunces. Dettwiler lost his leg and bled out before anyone could do anything . . . and his body was left behind in the chaos and worsening weather. Such a disgrace!

What Thomas should have done from the very start was to pull the general into his tent and show him what he meant, how the narrow road up from Zernez was not as narrow as everyone thought, and that a determined commander could push his troops a little harder and reach the critical road juncture in half the time. Thomas knew this. He knew, because he'd walked that same narrow pass but five months ago and had painstakingly mapped out the road himself on hexagon paper. He knew because he'd played out the ambush with dice and blocks. He knew, because he'd gone to Grantville and studied American methods of war.

He could have easily gotten copies of books that had come out of Grantville. Even in Switzerland, there were plenty of texts about American wars fought from the eighteenth Century up to the Ring of Fire. But that hadn't been good enough. Thomas had needed to see these Americans up close and in person. He needed to divine their secrets by being in their town, by seeing how they walked, how they talked. These up-timers had handled themselves in battle surprisingly well since their arrival. Breitenfeld. Luebeck Bay. The Baltic Sea. It came as no surprise to Thomas that a large part of their prowess in battle was their superior weaponry. The League of Ostend had learned of that power the hard way. But there had to be something more, something tangible and qualitative that could only be discerned by being among them. Thomas had to find out.

So last autumn he had been given permission by his rather reluctant father to visit Grantville (with "quiet" allowances from the USE). General Dettwiler nearly dropped from his chair when he heard. "The kalbfleisch is going off to learn war in a bookshop!" he had said, laughing, shaking his head and slapping his knee. "Be careful not to cut your throat on their wicked parchments, for I would dearly miss my young, bookish, half-baked boy!" Thomas was happy that he could give the old mercenary such a cozy chuckle, but patiently took his leave before anything else was said. General Dettwiler was a skilled field soldier and mercenary and he had fought bravely on many battlefields. But he lacked imagination, and that, Thomas knew, was the future of warfare. With the arrival of the Americans, everything had changed.

He did not find what he was looking for initially. Day after day he pored over the books, much to the curiosity of the librarian Marietta Fielder, who watched him arrive each morning and then leave each night. There were dozens upon dozens of books and old war movies, some with amazing pictures and footage showing the allied offensive in the Argonne Forest during World War I, and the landings of the US 29th Infantry Division at Omaha Beach, World War II. He marveled at the bravery of Pickett's Charge at Gettysburg, and sat glaring in terror at a mushroom-shaped cloud over a Japanese city called Hiroshima. Page after page and reel after reel of war stories and eye-witness accounts. It was slow going with his elementary knowledge of English, but he pressed on, with eyes blood-red and weary by each day's end. He could not find what he was looking for. What was he looking for? He asked himself again and again. What do I hope to find? He knew the answer, but was afraid to admit it. I want to learn how to fight. I want to learn how to beat Gremminger and his Ostend dogs! But the answers were not lying there on the pages of those marvelous books or in the bright images of those wonderful films.

He was about to "throw in the towel," as the American expression went. Then he saw two boys, only five or six years younger than he, sitting in a corner hunched over a table covered with a map, with tiny pieces of cardboard strewn around in hexagon-shaped locations. It was a map of Europe and Northern Africa. It was a better-looking map than many hanging in the richest homes in Zurich. The boys were talking, ribbing each other, throwing dice and checking charts and tables. Occasionally they would move the cardboard pieces, flip them over, add new ones to this country or that, and were having a grand old time generally. Thomas hadn't realized just how close he'd gotten to them until one of them spoke.

"Hey, man, you're hogging the light!"

Thomas had no idea what that meant, but he backed away. "May I ask? What are you doing?"

He spoke in broken English, which neither seemed to understand fully. He tried again slower and with more care.

They nodded but were surprised at the question. One of the boys screwed up his face as if he'd bitten a lemon. "We're playing a game."

"A game?"

"Yeah. Have you never played a game before?"

Thomas nodded. He knew chess and was himself a pretty fine player, but he had never seen anything like this. "What kind of . . . game?"

They looked at each other. Then one said, "A wargame."

Kriegspiel? He'd never heard of anyone playing that on a tabletop. Chess was considered an abstract form of war, of course, but this? This seemed much more complicated and exacting, and he was enthralled.

So he sat with them and watched for the next three hours, studying their moves and listening to them talk. When they took a break, he asked questions, studied the pieces. "What do all these symbols mean?" he asked, and they pointed out each number, each symbol on the front and back of the counters. Some were infantry units; others, armor or artillery. The unit size of each counter ranged from Division up to Corps and Army. They were playing a "Strategic-Level World War II" game, one that had been donated to the library by friends of a young man named Larry Wild who had died in a naval battle just over a year ago. Thomas was so fascinated by this game that he found himself talking to them about his own problems.

"What you need are some good pike and shot or Napoleonic miniatures rules," said the boy named Joe Straley as he dumped his German counters into their plastic bag.

"Yeah," said the other boy, Sandy Eckerlin, as he folded up the map. "Something with a small unit count, something on the tactical level."

Thomas shook his head. "How do I find those?"

Sandy put the bag back into the game box and scratched his head. "I don't know. Let's see if there are any on the shelves."

Alas, there were not. Larry Wild's collection included many wargames, but no miniatures rules. "Well, no problem," said Joe. "We can figure something out."

For the next two days, they used one of the research rooms and hammered out some rules, decided that using a hexagon-based movement system (like the game they had been playing) was the best approach. A half mile per "hex" seemed appropriate; the distances between Davos and Zernez and its surrounding smaller towns weren't excessive; thirty to thirty-five miles at the most. They discussed the kinds of weapons the armies had, the number of men, the appropriate movement speeds of foot versus cavalry versus cannon. Sandy recommended that they find some old army men and glue them to bases to serve as "proxies" for Thomas' soldiers. Joe laughed. "Are you kidding? Who's gonna believe German grenadiersposing as Swiss pike?"

"They don't have to be believed, Joe," Sandy said, a little put out. "It's just a game."

The two days were up and Thomas had scribbled enough notes to fill a notebook. Before he left, he invited the boys to serve as his aides in camp, but their parents flatly refused. "My son isn't going to Switzerland to get himself killed in no foolish war," said Eckerlin's mother, and Joe's parents weren't very diplomatic about it either. Thomas understood. He thanked the boys profusely and before he left, Joe slapped a leather bag into his hand.

"Here, take some dice with you," he said. "There's an old twenty-sided in there and a few twelves and tens, but mostly six-siders. Larry Wild's old stash, used to slay dragons and orcs in D&D, I reckon. I don't think you'll be doing any of that, but they may come in handy."

Indeed they did.

****

Gremminger unbuttoned his grey wool coat. It was still cold, but the sun was high, and across the snow-topped mountains in the distance, there was sufficient heat to make the day pleasant. It was made even more pleasant by the formation of Spaniards who stood at attention before him in ranks of twenty men each. Tarasp had promised and had delivered, and in impressive numbers. "Two hundred fifty," Gremminger said, his eyes lit up like candles. "A good variety of weapons too, I will say. The Spanish have been busy."

Captain Luis Mendoza y Rodriguez nodded his appreciation, and said, "Thank you, Herr Gremminger. Spain is delighted to be of assistance in this most dangerous endeavor. I wish I could say that Bishop Mohr had delivered these men to you, but you understand his situation, I'm sure."

Yes, he did. The Bishop of Chur, Joseph Mohr von Zernetz, had always supported the God's House and its standing in the Grisons. Chur was the capital of the League, of course, but since the arrival of the Americans and the subsequent creation of the USE, Mohr's allegiance had come into question. Pressure from German and Italian interests (both financial and political) had put entirely too much strain on the old priest, and his health was failing as well. Now close to death, he'd gotten soft and indecisive. Gremminger had given the man a chance to prove his loyalty by requesting support. Mohr had refused. Gremminger shook his head. At least some of the Hapsburgs in Tarasp still had back-bone. But . . . "You understand, Captain Mendoza, that my quarrel with Gregor von Allmen has nothing to do with the League of Ostend and their political mechanizations. My purpose is strictly mercenary, as the saying goes. Von Allmen stole land from my father. I intend on getting it back." He turned and faced the Spanish captain. "Entiende?"

The feud between the Gremminger's and von Allmen's went back thirty years, when a mutual agreement was made to swap disputed lands. The agreement seemed to be holding, until the young, impetuous Gregor von Allmen took it upon himself to violate the agreement and reclaim those lands. The Gremminger's had not been in a position to protest in force at the time. Such was not the case now.

Mendoza nodded and Gremminger could spot a tiny wink in the Spaniard's right eye. "Of course, señor. My associates in Tarasp just feel that, in these troubled times, it's best to show support for a fellow Catholic who has expressed his el amor que no se muere . . . oh how do you say it? His . . . undying love for God and for the Valtellina."

"Of course." Gremminger nodded. Then he noticed the gun strapped to Captain Mendoza's back. He pointed to it. "What's that?"

Mendoza's face spread in a mighty grin and he swung the gun off his shoulder and presented it to Gremminger. "Ah! This is what I wanted to show you. New weapon, fresh out of manufacture. There aren't many of them, understand, but enough to make quite an impressive showing."

"What is it?"

Mendoza turned it round and round in his hands. "It's what the Americans call an 1853 Enfield muzzleloader, used with minié ball, housing a flintlock ignition system. It has an engagement range of nearly four hundred yards, and an effective range of two hundred fifty yards. A good man can fire two, perhaps three, rounds per minute."

Gremminger took the rifle and studied it. "How did you get it?"

"The Americans aren't the only ones who can make weapons, señor. This particular piece was made in Suhl, you see. They are difficult to produce, but not impossible."

"How many do you have?"

"Twenty." Mendoza turned to his men and said, "Presenten!"

Twenty among the ranks held up their rifles. Gremminger looked at them, delight covering his face. Not only had his army swelled to just over a thousand men with the Spanish arrival, but its firepower had grown precipitously as well. Spread out over so many ranks, however, did not make sense; their effectiveness would be diminished in the din of battle. But together . . .

He tossed the rifle back to Mendoza and said, "Captain, please extend my thanks to your associates for this pleasant gift you have offered. We accept Spain's support, and we welcome you to Zernez. I think you will find the air and the fighting here most agreeable to your warrior sensibilities. My spies tell me that our opponent, Thomas von Allmen, sits day and night in his tent, toiling over what we do not know, but I suspect he's pulling out his fair hair over what to do. He's young, inexperienced, and has never led men into battle. Let him rot in that tent for all I care! With your arrival, victory is all but assured, and with your new guns, it's simply a matter of time. But if I may, I would like to take your Enfield riflemen and put them into one unit. And, Captain, can your men ride horses?"

Mendoza nodded. "Certainly, General. The Spanish are born in the saddle. What do you intend?"

Gremminger turned and looked over the horizon, toward the wall of snow-capped mountains. He smiled.

"I have an idea."

****

"That's the most ridiculous idea I've ever heard!"

Captain Lukas Goepfert was never one to restrain his opinion, and as Thomas moved his blocks in the manner most objectionable to his older confidant, he smiled. "You forget, Herr Goepfert, that I know what I'm doing."

Goepfert huffed. "That's debatable. Captain Elsinger's cavalry will cut you to pieces."

Thomas smiled again and moved his smaller, less-effective pike block into an adjacent hex. The unit had already suffered losses and was marked with a tiny flag that indicated its "shaken" status, which meant that if it took additional casualties or was forced to retreat in the face of an unshaken cavalry unit, it might "rout" out of existence.

Elsinger, who was in command of Gremminger's army (seventeen blocks strong), smiled and moved his fresh cavalry block into the space with the shaken pikemen. "Don't forget, Elsinger, that you must first take a morale check before moving your cavalry into my space."

"What?"

Thomas nodded. "That's right. Entering the frontal arch of a hex occupied by a pike block, regardless of its status, requires a check."

Elsinger picked up his dice, shook them rudely, and tossed them into a wooden box near the tabletop. He rolled a five and a one. "Let's check the chart."

Thomas grabbed the morale chart which he had carefully scripted onto a piece of paper, cross-referenced the numbers rolled and got the result. "Your unit is hesitant, which means that it can still perform the charge, but its strength is reduced by one to a four."

"Ridiculous!" barked Elsinger.

Thomas shook his head. "Not at all. My men may be weakened but they still hold eighteen-foot poles that will tear your horses to shreds. Your cavalry follow orders, Elsinger, but remember that they do maintain a certain amount of self-preservation. We're not dealing with Huscarls or Japanese samurai here. Thank God you didn't roll snake-eyes! Your charge would have been over before it began."

"And if I had rolled boxcars?"

"Then my men would have routed away and you would have been able to pursue and conduct an overrun attack," Thomas said, growing impatient with his captains' lack of memory of the rules. They had played this scenario many times, and he had not created a rule set that was overly complicated. He'd only incorporated basic, simple principles of war. They should be old-hats at this by now, as the Americans might say. And he had made it even easier by allowing them to play on an open tabletop.

The most ideal situation, of course, would have been to establish a double-blind environment, where the opposing forces and commanders were in separate tents, thus creating a proper "fog of war." Such a setting, however, was not possible. Thomas had neither the time nor the resources to construct and train for such play. Perhaps someday he could, but Gremminger was on the move, and real men would be dying soon. They needed to get this right, and quickly.

"Your cavalry is under the command of Captain Murner," Thomas said, pointing to the command block, "one of Gremminger's best. I have him rated as steady so you will not suffer any further strength loss due to commander unreliability, but my pike will receive a defense bonus of one because they are within range of Goepfert's command block, plus they have fresh snaplock skirmishers stacked with them in the hex, which helps to strengthen their resolve."

"Why won't your skirmishers have to take a morale check?" Elsinger asked.

"Because that's what skirmishers are for," Thomas said, "screening pike blocks and reducing the effectiveness of cavalry charges. If they fail in that by breaking before a charge, their officers should be shot!"

"And why aren't we working in tercios? You've got all the blocks sorted out into their respective weapon types. They should be combined."

Thomas shook his head. "Tercios is a Spanish formation."

"Not exclusively. Other nations use it at as well."

"It's a fine formation, Elsinger, but we don't have enough men for tercios." Thomas' frustration was growing again. "That only works well with thousands. We've less than eight hundred. If we start mixing our unit types, they'll be less effective. We need concentrated firepower for narrow passes. Besides, we are in effect working in tercios anyway, since I allow stacking, so pike blocks can stack with cavalry, with guns, and so on. Now, let's proceed."

Thomas picked up two ten-sided dice and handed one to Elsinger. "You're going to get destroyed," Goepfert whispered into Thomas' ear. Thomas nodded. "Perhaps."

They rolled off in the wooden box. "Okay," Thomas said, "you rolled six and I rolled three. Now we add our respective combat strengths to our rolls to get a total of six and ten. Let's check the combat result table."

Thomas had opted for ten-sided dice for combat because it gave more result gradation as opposed to a single six-sided die, or even two sixes. Being able to roll a natural zero also gave you the option of using it as a zero or a ten depending upon your combat model, and allowed for critical success or failure. The numbers that they rolled were pretty average.

Thomas checked the chart and said, "Your roll of four greater than me gives us a result number of two with asterisk, which means that I can either take two damage points, stand my ground and roll another round of combat as a melee engagement, or I can take one damage point and retreat one hex and allow you a free pursuit. I would only take that option, however, if I could retreat to terrain which would give me a better defensive bonus." Thomas pointed to the map. "As you can see, there are no such terrain elements in that area."

"Ah!" Elsinger said, almost giddy. "Then you'll take your two points of damage and be destroyed."

"Not yet. Remember, I have skirmishers in the hex, which allows me the option of trying a screened retreat."

"It'll never work."

Thomas ignored the comment and rolled his die. "I add my skirmisher unit's screen value of three to my seven and I get a ten, which is twice the value of your cavalry unit's current movement value. So this allows me to retreat my wounded pike unit one hex. I still take a point of damage, which will prompt another morale check, but my successful screen prevents you from pursuing. And . . ."

"Now it's our turn," Goepfert said, leaning over the map, "and his cavalry is stuck in position, fighting off stubborn gunmen, while my cavalry can sweep around there . . . and charge from the rear arch."

Thomas smiled. Finally, they were understanding things, seeing how the rules affected movement, how their combat and skirmish values (which they had helped to formulate in the dead of winter last December) affected enemy cavalry movement. They were seeing how each commander's psychological profile (steady, rash, cautious, bold) altered the overall combat effectiveness of their units. They were getting it, and he was relieved.

"Yes," Elsinger said, tossing his die down and tipping his cavalry block over, "but if you had rolled poorly at any time during this exchange, you would have—"

"I might have routed or exploded in place, which would have given your cavalry an overrun bonus and you would have been able to reposition yourself for a counter attack. Yes, I know the rules."

Thomas put down his die. "This is not about winning and losing, gentlemen. If I had rolled poorly, I would be as satisfied in defeat as I am in victory. Kriegspiel is not about victory. It's about practice—being able to put our men through their paces without actually expending them in the field, without forcing them to slog their way through passes choked in snow, at altitudes that make the most stalwart soldier lose consciousness. We can keep from expending materiel that we cannot afford to lose. We can practice tactics, like we have been doing, again and again and again, and see what works, what doesn't, and then adjust our numbers, our variables, until we're satisfied that we've got it right. Each time we win here, we try it again and employ a different tactic. We see what works, what doesn't, and hopefully on the battlefield, you will employ the lessons we've learned.

"Gentlemen, I know what's said of me. I know I'm kalbfleisch, and I know losing Dettwiler was a serious blow to the morale of our men. Even my father contemplated striking a deal with Gremminger. But what's done is done. All I can do is use the gifts I've been given by God. I'm the lowly third son of a powerful father who's nearing death. My oldest brother awaits this event with eager humility. My other brother worships our Lord in Lucerne. I have this," Thomas pointed to his head, "and mathematics. Mathematics is the universal language, and it is possible, with careful and diligent manipulation, to use it to model war. That is what we do here. That is what I learned in Grantville."

"But sir," Goepfert said, quietly, "there may come a time when you will have to put the dice down and lead your men."

Thomas nodded but felt the tears of fear well in his eyes. God help us all.

They were silent for a long moment. Thomas blinked, shook his head, and said, "I think you're right, Elsinger. I think our skirmish values are too high. We'll reduce them to a five and try again."

Before they finished setting up for another go, a messenger entered the tent.

"Yes, what is it?"

The boy nodded and said, "My Lord, Captain Buss says that Gremminger has received Spanish mercenaries."

"Bastard Hapsburgs!" growled Elsinger.

Thomas's heart sank. "How many?"

The messenger shook his head. "Could not get close enough for an accurate count, but he suspects one hundred, one hundred fifty . . . maybe more. And, My Lord, some of them have up-time rifles."

"What kind?" Goepfert said.

"We do not know, sir. But they're rifles for sure. Our man watched them drill. They're powerful. At least twice the effectiveness of our own guns."

"How are they positioned in the ranks?"

"They aren't in the ranks, my Lord. They comprise one unit of twenty. And they're being fitted as riders."

"Cavalry?" Goepfert seemed shocked.

Thomas grit his teeth and backed away from the table. A unit of twenty Spanish riflemen on horseback, firing at twice the effectiveness of his own snaplocks. They'd probably field at three times effectiveness in practice, though, for just having those weapons in hand would embolden them beyond their normal strength. They certainly could not fire effectively on horseback, especially in this rocky terrain, so they will likely dismount and take a defensive position like cavalry did in the American Civil War, or like Irish hobilars. But they would be fast, mounting and moving out of harm's way and appearing somewhere else to harry his men. Thomas shook his head.

Gremminger, you sneaky son of a bitch.

He turned back to the tables. "Okay, the die is cast. Gentlemen, return to your commands and get your men ready. It's time to face the Catholics." He leaned over the map and began resetting the blocks into their starting positions. "I want continual reports, by the hour. Understand?"

"Yes, my Lord," Elsinger said. "What will you be doing?"

Thomas looked up and smiled. "I'll be here . . . running the numbers."

****

"Dismount!"

Captain Mendoza gave the order as his cavalry cleared the tiny creek running down the center of the pass. Men came off their horses even before they slowed and some tumbled into the water, breaking their fall by dropping their Enfields and catching themselves before impaling their bodies on the sharp rocks below the melting ice. Mendoza cursed and helped a man to his feet, gave him back his rifle and pushed him to the bank. "Get ready to fire!"

About a hundred yards ahead of their position stood a thin line of pike, taking cover behind piles of rocks and fence rails. Mendoza knelt down, loaded his weapon, and set the barrel carefully in the crook of a tree. He cocked the hammer and waited until every man was ready.

"Fire!"

Down the line the Enfields fired, plumes of smoke following the minié balls as they rifled out of the long barrels and struck the breastworks in front of von Allmen's pikemen. The sheer force of those powerful bullets tore the railings apart, and men behind them wailed as their legs and arms were shattered by low muzzle velocity wounds.

"Reload!"

They loaded their guns and fired again, and another round of fearful screams filled the cold Alpine air. Those still alive after the second volley began to retreat and Mendoza ordered his men back in the saddle to pursue.

On and on it went for the next several miles. Where are their guns? Mendoza wondered. Where are their cavalry? Just one pitiful little screen after the next, ten to fifteen men each. Mendoza considered charging the fifth screen line but reconsidered at the last moment. He only had twenty men, whose purpose was to move up this pass quickly and outflank von Allmen's army. Gremminger had assured him that this route was easily traversable and that Mendoza should not worry. "Von Allmen doesn't know war from waste," he said. "You'll move fast and hit him from the rear while I move my army down the Flüelaand strike like a hammer. Once in position behind his lines, find good ground and kill them on the retreat."

But the pass was too narrow to maneuver around the pike screens, and if he tried, he'd lose men. He couldn't afford to lose a single one.

On the seventh screen, he ordered a retreat. "Gremminger be damned," he said and kicked the sides of his horse.

Three miles back, guns began to fire along the ridgelines.

Not cannon, for it would have been impossible to put such heavy barrels among the thick spruce, but snaplock, flintlock, and the occasional wheellock. Two or three men in each team, spread thin among the trees, taking single shots at Mendoza's men as they tried to gallop out of harm's way. But the creek split his force, and their retreat was slowed by bullets hitting their horses. When the third horse went down, Mendoza realized that they were not trying to shoot his men; they were purposefully targeting the horses. It made sense in a way, Mendoza admitted. Trying to hit a moving target with inaccurate weapons was difficult at best, so why not target the biggest piece of flesh on the field? Another horse went down, and suddenly his men stopped, turned in the saddle or pulled themselves out of the water, and began shooting wildly up the ridgeline.

"Bastante!" Mendoza said, pulling his saber and whipping it into the air. "Enough. Don't waste shots. Remount the fallen men and move! Muevan!"

For the next three miles, Mendoza's impromptu hobilars fought for their lives. By the time they cleared the pass, they had lost twelve horses, five men, and Mendoza himself had been shot in the right arm.

****

"Gremminger disrespects me," Thomas said as he removed the wooden sticks from the map that had represented the entrenched infantry screens. "But damn him, he won't anymore. That bloodied his nose."

Goepfert nodded. "Yes, but we lost seventy-two good pikemen. We can't afford losses like that for such little gain."

"Little gain?" Thomas leaned over his chair and picked up an Enfield rifle that had been rescued from the creek during the Spanish retreat. He hefted it, set the butt against his shoulder, and looked down its long barrel. "Nonsense. The Spanish are back on their heels, and that pass is closed for good."

Goepfert shrugged. "Gremminger will simply refit what remains and try something else."

Thomas set down the rifle and pointed to the map. "And so will I. Are the men ready?"

"Yes, My Lord, but I wish to advise against your plan. It's too risky."

Thomas furrowed his brow. "How so?"

Goepfert leaned over the table and motioned to the twelve blocks arrayed along the Flüelapass. "You're ordering an attack, and it has always been the policy of this army, and of your father, I might add, to defend ground, thus off-setting the numerical superiority that Gremminger has always had. You are asking us to attack, and that, by definition, escalates this engagement beyond our purview, our political scope. If you attack Gremminger, My Lord, you are giving ammunition to his supporters in Tarasp. You are giving ammunition to the Hapsburgs and their desire to ally the Grisons with the League of Ostend. Your father is against the League, of course, but if he's seen as being the aggressor in this engagement, then the Zehngerichtebund will have to move quicker than it intends, and they may well cut their ties with your family and let us burn."

Thomas pointed at the Enfield. "The Hapsburgs have already escalated this by giving Gremminger Spanish troops with up-time weapons. The die is cast. Let us not suddenly lose our wits on this truth. No, sir. The God's House has made its decision, Goepfert, and we are fools if we do not act in kind. My father is dying and my brother, Lord save him, doesn't have the skills to skin a cat. He is weak and our house will fall whether we defend or attack. If we hold, we die slowly. If we attack, we may still die, but we will die with honor. This plan will work. You know it will."

Goepfert leaned against the table. He smiled, but Thomas could sense the man's growing impatience with his young commander. "This isn't a game, Thomas. This is real."

For a long moment, Thomas stared at his captain. Perhaps he's right, Thomas thought, as his hand found some dice and scooped them up. How dare I speak of honor when I'm afraid to leave this tent? I'm a coward, hiding behind blocks and maps and charts. What do I know about war? Perhaps he's right. Perhaps . . .

Thomas opened his fist and looked at the dice. He counted the pips. He closed his hand and said, "This conversation is over, Goepfert. I've made my decision. I want you to lead the men."

Goepfert sagged, defeated. He nodded. "Yes, my Lord. But . . . perhaps Elsinger would be a better candidate for command? He's younger and—"

Thomas shook his head. "No. Elsinger is rash. You're steady, and your excellent tactics on-map correspond perfectly to your past performance and reputation in the field. Dettwiler placed his faith in you, and so shall I. You can lead the men, and you will."

Goepfert sighed and nodded. "Yes, My Lord."

As Goepfert left the tent, Thomas placed the dice carefully on the table. He counted the pips again.

Snake-eyes.

Failure . . .

****

He's crazy. The boy has lost his mind.

He would never say this to the boy's face, but Lukas Goepfert feared for Thomas' soul. Not in the traditional sense, with brimstone and lightning bolts from the clouds, nor did he think the young von Allmen would burn in Hell. But his soul, his essence—and in Thomas' case, the seat of the soul was the mind—had fallen hard under the American spell. They weren't wizards, as many detractors liked to say, but they were dangerous, and they had poisoned Thomas into thinking that he could learn war from a game. What folly!

And yet, Goepfert admitted, there was some practicality to it. Their tabletop exercises had ferreted out some weaknesses on both sides, and it was easier to "try things out" as Thomas might say, without having to put the men through rigorous drill that might, in the end, prove fruitless. And, it was kind of fun. So maybe the kalbfleisch had something in this wargaming business after all. But to declare Elsinger "rash" was silly. Elsinger might be young, and yes he was impatient at times (and wasn't very good at playing the game), but no one could question his resolve, his loyalty, or his fighting spirit. In Goepfert's experience, such individual élan had turned many defeats into victories. No wargame could anticipate the minute by minute changes on the battlefield, nor the stresses that could turn a stalwart into a crying baby, or a coward into a hero. Only through experience could a commander know and anticipate these things. And what of direct leadership? A good commander cannot lead from a tent. Being visible to your men and sharing their sacrifice could turn the strength of fifty into a hundred. Mathematics mattered, yes, but heart was just as important.

"Captain Goepfert!"

Behind him, behind the long ranks of pike and musket that moved up the narrow pass, Elsinger arrived with his cavalry. The pike moved aside and gave the road to him and his men. He came alongside Goepfert, saluted, and said, "We must make Susch within the hour . . . if we are to follow Thomas' plan and remove its citizens."

It seemed to Goepfert that the young cavalry officer was trying to solicit a negative response to the order, but he ignored the intent and said, "Yes. Move your men along quickly and keep me informed of Gremminger's dispositions. You're supposed to act like Jeb Stuart, our beloved commander has said. I don't know who the hell that is, but you are going to be the eyes and ears of this affair."

Elsinger shook his head and spat onto the ground. He growled. "We should fight in tercios. You know that."

"No. On this, I agree with the boy. Our supplies were sacked when Dettwiler fell. We do not have the ammunition or the runners to distribute it among the units. We have to keep them in three separate blocks, snaplocks, calivers, and muskets alike, until such a time as they are needed and can be moved accordingly. Besides, these passes are narrow enough that there is little concern of being outflanked, and that's where you come in. You have to keep Gremminger's cavalry off my infantry until I can move into town and position our men."

"We shouldn't be attacking at all."

"I know."

"Then why are we?"

"Because we've been ordered to!"

Goepfert looked down. The army was moving forward, slowly but deliberately, their pikes, guns, halberds, and swords glistening in the sunlight. If they noticed his agitation, they did not show it on their faces. He sighed, put up his hand, and whispered, "I know you're concerned, Elsinger. So am I. But we follow our commander's orders. We follow them . . . until I say otherwise. And then, we will do what we have to do to preserve the army. Understand?"

Elsinger nodded.

"Now get going," Goepfert said, patting him on the shoulder. "Be our eyes and ears."

The cavalry moved down the road, and Goepfert led his horse to the embankment to let the infantry continue its march. He studied them with admiration. They were good men, some mercenaries, many farm boys, most dirt poor, but they were willing to fight and die for the von Allmens. They didn't want Gremminger on their lands any more than they wanted a pope telling them how to pray. But Goepfert felt like a butcher leading lambs to slaughter. Oh, Thomas, my dear boy. What do you see in your mathematics that makes you think we can win?

Goepfert looked into the bright sky toward heaven, but the answer was not there.

****

Gremminger watched as his men moved toward Susch en echelon, their frontage protected with musket skirmishers. It was the traditional formation for Swiss infantry, and it had held his country in good stead across scores of European battlefields. It would serve its purpose here too, he knew, as they moved forward quickly and took up their positions on the edge of town to the cadence to martial drums. Two solid blocks of one hundred pikes each, with the middle block comprised of Spanish halberdiers for up-close fighting. Looking at the Spanish formation, Gremminger was relieved that he had managed to calm Mendoza down and convince him to stay. The poor bastard was ready to quit the field after his cavalry was routed. Gremminger had never heard so many Spanish curse words in all his life, and he couldn't help but chuckle a little. But only a little. The kalbfleisch had surprised him. It was a clever move, and one that Gremminger would not fall for again.

He was disappointed that von Allmen had arrived in Susch before him. Murner's cavalry, usually very good at holding the enemy at bay, had not moved as quickly as advised. At least the good townsfolk were gone, it seemed, as Gremminger peered through his glass. They'd left in a hurry. That's good, he thought. Sometimes it was difficult to know which side these small towns were on, so close to the border and so readily influenced by outside events. He smiled. At least he wouldn't have to worry about killing innocent people.

On the other side of town, ten small blocks of infantry lay with a smattering of musket support. Gremminger looked through his field glass and sneered at the banners waving in the breeze. Most of them were displaying the traditional God's House Ibex on mixed white-and-red fields, and some with smaller coat-of-arms at the top of a white shield. Von Allmen had no business waving such flags. He and his supporters had cast their lot in with the Ten Jurisdictions and the USE; God would punish them in good time. As I will punish them today, he thought as Captain Murner arrived with his cavalry. I will bring those banners down, and we will walk across Ibex bones all the way to Davos.

On the other side of town, ten small blocks of infantry lay with a smattering of musket support. Gremminger looked through his field glass and sneered at the banners waving in the breeze. Most of them were displaying the traditional God's House Ibex on mixed white-and-red fields, and some with smaller coat-of-arms at the top of a white shield. Von Allmen had no business waving such flags. He and his supporters had cast their lot in with the Ten Jurisdictions and the USE; God would punish them in good time. As I will punish them today, he thought as Captain Murner arrived with his cavalry. I will bring those banners down, and we will walk across Ibex bones all the way to Davos.

"You're late!"

The cavalry officer saluted quickly and said, "My apologies, General. Elsinger has been harassing our approach all morning. We drove them off finally, but . . ." He hesitated. ". . . they took out one of our guns."

"Destroyed the carriage?"

Murner shook his head. "No. They spiked it. Hammered a nail down the touchhole and broke it off."

Gremminger grit his teeth. Von Allmen had at most two cannon. Now there was parity. Damn! He shook his head. "Get the other two up here quickly and place them where I have directed. And I want you to split your men; thirty to the right, thirty left. There's just enough gap on either side of the town to infiltrate. Once behind their blocks, reform and charge. Do you hear me?"

Murner nodded.

"And get those Spanish Enfielders back in the saddle. There aren't many left, but by God's Grace, we'll use them."

"Yes, sir!" Murner kicked his horse and rode off.

Gremminger looked through his field glass. On the ridgeline far to the rear of the enemy position, he saw the command banner of Captain Goepfert. He nodded. A good soldier and the right choice. "But, Goepfert," he whispered as he watched his cavalry form up and move towards the flanks, "are you going to follow your own judgment, or are you going to follow the boy like a good servant?"

He prayed for the latter.

****

From the ridgeline, Goepfert watched as Gremminger's cavalry tried outflanking his small blocks of pike. But as the cavalry advanced, the flanks pivoted and reformed en echelon. Murner's men were peppered by musket fire and some fell dead into the front block on the right side, scattering the men and forcing a gap in the line. Murner exploited it and flooded through, his horse scattering out and swiping terrified faces with sabers and taking shots with wheel-locks. "I have provided the strategy," Thomas had said, "you provide the tactics."

His instincts told him to reform his infantry into larger blocks to thwart the enemy troops now moving through Susch. When they hit, his tiny blocks would not hold. It would be a rout worse than the Dettwiler debacle. Goepfert looked down at the raging battle. He sighed. Give the kid a chance.

He looked at his bannerman and nodded. The young boy waved the banner as designated and one after the other, the small blocks turned their ranks and formed hedgehogs or what Thomas called "French Squares" as employed at Waterloo. Geopfert had never heard of that battle but it seemed to be working. The cavalry flowed through the blocks like water, poking and prodding as they went, trying to find weaknesses in the tight squares. But the pikes and halberds were holding well, and the snaplocks that had squeezed into their centers fired, protected by the forest of polearms, reloaded and fired again, taking horse and mount down and spreading the cavalry even thinner. Goepfert nodded. It was working.

Time to launch the second part of Thomas' plan. He looked to the center of the town. As the boy predicted, Gremminger's pike and halberdier blocks were too large to move through unimpeded. They divided around the buildings. The Spanish halberdiers were spread even thinner, taking the tack of stretching their line down the center street nearly in column. But there were so many of them. Three hundred total, including skirmish support. Even if the plan worked . . .

Goepfert gave the nod, and the bannerman waved his flag again. Nothing happened at first, then one after another, small popping sounds spread across Susch as windows opened, loft doors sprang free, and lines of smoke filled the sky as small-arms opened fire on the confused enemy infantry. A mighty roar went up through the ranks as men fell bleeding from head and chest wounds. Thomas had specifically ordered that officers be shot. It was an unprecedented move in the Grisons. Unthinkable, in fact, to shoot an officer. Not that it never happened in battle, but to order it, to specifically call for the assassination of the sons of important Swiss families, would have ramifications far beyond the border of this small Alpine village. "War is hell," Thomas had said, quoting some American general from a book he had read in Grantville. Indeed it was, and now von Allmen was bringing that hell to Switzerland, killing boys like himself by the bushels. But he wasn't killing anyone, was he? He was sitting in a tent, rolling dice, running the numbers, while his men were being encircled.

And so it was. The initial shock of the plan had killed many of Gremminger's unsuspecting soldiers, and had held up their advance. The Spanish even fell back out of the town. But the skirmish lines in front of Gremminger's infantry fired back at the buildings and pinned the ambush. This gave the infantry time to reorganize and storm the buildings, smashing the doors open and racing up the steps to kill the surrounded gunners. One after another, the buildings fell silent.

The small pike squares had done their job against the cavalry. Murner had ordered a retreat, and Elsinger's cavalry would make sure they did not return. But there were two other cavalry units out there in reserve, plus another four hundred men awaiting orders. "We're fighting a war of time," Thomas had said. "We need time for the politics to evolve, for Davos to make good on its promise. Time is what we fight for."

Goepfert spit onto the ground. It's all just a game to you, isn't it, boy? We're all just numbers. You've supplied the strategy, indeed, but it's time you got your nose bloodied. Here's a tactic for you!

He motioned for a runner. The boy appeared beside his horse. Goepfert took a piece of paper and one of Thomas’ Grantville pencils out of his coat pocket and handed it over. "Write this down, word for word, and deliver it personally to Lord Thomas von Allmen."

As he spoke the message, the boy's eyes grew large. When he finished, the boy folded up the paper, put it in his pocket, and handed the pencil back to his commander. "Sir, I don't understand this message. You're not—"

"Hand it to him personally, Karl," Goepfert interrupted. "Do not speak a word to him, and do not look into his eyes. If he sees your eyes, he'll know you're lying. He's too damned smart for his own good. Go!"

Karl saluted and was gone.

Goepfert looked through his field glass at the battle below. His infantry were out of their squares and back into normal formation, waiting Gremminger's infantry as it fought through the streets of Susch. From this vantage point, it was easy to see how even two cannon, carefully trained right down the center of the town, would . . .

The boy is too damned smart for his own good.

Goepfert lowered his field glass, put up his left hand, and said, "Fire the guns!"

****

"I swear to the Almighty, Mendoza!" Gremminger screeched above the roar of battle. "If your men retreat one more time, I'll kill them myself. No quarter!"

The Spanish captain sneered and turned away. Gremminger watched him disappear among the confusion of Spanish infantry trying to re-form in the center of the town. The Swiss pike, at least, were doing well, but it had become a massive, confused infantry squabble, as Geopfert ordered cannon fire from his ridgeline. The first few shots had torn through Gremminger's men like butter, and the Spanish had lost a dozen in the first shot. Bits of brain matter and bone had even spattered Gremminger's legs one hundred yards away. He got off his horse quickly. Either that, or retreat back to the protection of his own guns. But why haven't they fired? Why?

And then they did. Gremminger had never heard anything so wonderful in his life. Finally, his guns were ripping long bloody lines through von Allmen's infantry. Or were they? It was difficult to tell from this position, with the blocks all pushed together and with so much smoke floating above the town. He needed to get closer and see for himself.

He whistled for a runner. "Tell Captain Rauber to bring everything forward. No delay!"

"Yes, sir!" The boy saluted and ran off.

Goepfert had already ordered the rest of his men to engage. He'd thrown everything in, and so clearly this was where they intended to finish the job. But was it his decision or von Allmen's? And where was the boy? Why wasn't he here at least observing the battle? What the hell was he doing in that tent?

"Coward!" Gremminger said as he and his staff moved through the town carefully to get a better view of the battlefield.

****

Thomas' hand shook as he read the message. Captain Goepfert has fallen. You must come at once.You must lead the men.

It was signed by Elsinger. He read the message again, the words mixing with memories from his dreams. His hand would not stop shaking, like those soldiers from Vietnam who had suffered shell-shock, or what was called by American clinicians post-traumatic stress. But they had actually fought; pulled a trigger, thrown a grenade, put their hand in the chest wound of a fallen friend. What had Thomas done? Nothing . . . nothing . . .

He had been Dettwiler's aide de camp for only eight months, and he had never even fired a gun. He would never admit that to his staff, for they'd believe it certainly, and that would make him even less of a man in their eyes than he was now. But in the last few months he had found some courage. He had found a confidence that was lacking. Being the son of a Swiss lord gave him title and claim, but nothing else. Until now. These dice, these maps, these tiny wooden blocks he pushed from hex to hex had told him that he was smart enough to lead men into battle. Lead men? He was smart enough for strategic and tactical decision-making, but was he brave enough to lead?

Thomas grabbed the Enfield with shaking hands and bow-slung it across his back. It lay heavy against his cuirass. He was afraid the half-cocked trigger might fire, but of course it would not. Not until he pulled it.

He breathed deeply and stepped out of the tent. The sun was high and hot. He rubbed his eyes until he could see. In the distance, he heard cannon fire. Mine or his? Both probably. Numbers swirled in his mind, blocks moved, dice rolled.

He climbed his horse. "I'm going to the front," he said to the young boy holding the reins. "If I don't return, tell my mother, my father that . . . I tried."

He turned, spurred his horse, and galloped toward the sound of the guns.

****

Gremminger watched his infantry hit the center. The Spanish had come back strong, smashing into Geopfert's porous line and leaving large gaps, despite the man's efforts to put everything he had into the field. Parts of Susch were on fire, and Gremminger was truly sorry for that, but if it meant that von Allmen's army would finally be defeated and routed from the field, he was willing to take the political hit, regardless of the outcome.

"Get me a horse!" he yelled to a staff member.

He peered through his field glass. Remnants of Murner's cavalry coupled with the Spanish Enfielders slammed into one of Geopfert's small infantry blocks. They tried holding their ground, but one after the other, men were picked off by errant up-time shots ringing through the smoky air. Pikes cut through horses' necks, swords slashed down, faces exploded in a burst of sweat and red blood. The smaller enemy units were mobile enough to fill gaps in the line, but ultimately could not stand against Gremminger's larger units.

There was, however, something useful in smaller ranks, Gremminger had to admit. They did not possess the punch and potency of larger formations, but their size allowed greater mobility and allowed exploitation of open flanks. It was as if von Allmen was trying to fight a guerilla war. But you fight a guerrilla war by attacking, withdrawing, attacking, withdrawing, and you certainly did not do it with pike. Goepfert was not withdrawing. He was trying to maintain interior lines by pushing a superior force back. Clearly, the wishes of his young commander and his own practical field experience were at odds.

Gremminger nodded. It was time to exploit this rift in command.

His horse appeared at his side. He climbed into the saddle, unsheathed his saber, and said, "Let's get into this fight. No leading from behind. One more push and they'll crack. With me!"

The small cavalry unit that had formed up behind their commander followed him down the smooth slope of the road that split Susch in two.

At the edge of town, Gremminger raised his saber, leaned into his horse, and shouted, "Charge!"

****

The sounds of battle grew confused as Thomas drew near. The guns were louder but they were not his guns. He did not know how he knew this, but he knew. It was in the way that they fired. Two rounds and no response. No counter-battery. One side was firing, the other was not, and screams of pain erupted on the valley road that wound down from the Flüelapass, through the battle lines, and into Susch.

Thomas turned the corner and the fight came into view, lines of ragged infantry spread across the field like skins from a shedding snake. Red and white and blue shirts, grey coats, ibex, lion, and shield banners, coat-of-arms of smaller houses whose children and subjects lay in heaps on the bloody ground. It was difficult to tell the opposing sides for these were all Swiss boys save for the small detachment of Spanish that Thomas could barely discern through the bleak smoke. So many men dead on the field and yet they kept on, re-forming lines and going at it again. He couldn't help but feel a certain pride as he watched it all. It did not matter who was friend or foe. They were Swiss, and they never retreated.

But that was not true, was it? At Marignano, Swiss pike had been decimated and forced to retreat. At Bicocca as well. Two old battles, barely remembered by the Swiss people but now ringing clearly in Thomas' mind like church bells. And just a few short weeks ago near Zernez, another retreat had occurred, and so here he was, just a boy, looking down on carnage that he had never seen in his life. You must lead the men. But how? Around him, the dead and dying lined the pass, the small wagon train of his force choked with civilians from Susch that he had yanked from their homes to make room for death and desolation. As he brought his horse to a slow trot, they looked at him, paid their proper respects, and reached up as if he were the American president, Abraham Lincoln, come to Richmond to free the slaves. He reached down and touched their hands and tried to offer them some reassurance, some hope in the stench of the billowing smoke and fire that ran through their homes.

He'd made a mistake. He realized that now. He had saved the civilians by moving them out, but not their town. Putting gunmen into the empty homes was a way to slow the enemy advance, force them to stack up in the streets and perhaps convince Gremminger to pull back and reconsider a different route. Then counter-attack. Gremminger, however, had surprised him. The duke had been bolder than first thought, more ruthless, a bigger risk-taker. Thomas had run the numbers, had calculated Gremminger's skills and had built in variation for his psychological profile. Not enough variation apparently. Thomas had made a mistake . . . yet he'd been right as well.

It was clear that Gremminger's superior force was having trouble finding complete purchase of the field. He could not push through Susch with all of his men at once, and thus, he could not attack in force. It was a natural choke-point that slowed his advance and allowed Elsinger's cavalry time to function as hobilars, like the Spanish had tried to do. Their guns were inferior weapons to the Spanish, but it appeared that Gremminger had committed his remaining up-time weapons to the full battle, in desperation no doubt, trying to whip the kalbfleisch here and now.

You must lead the men.

Thomas scowled. It was a damn fool thing for Goepfert to do: getting himself killed at such an important moment. He pulled out his field glass and focused on the battle in the center of the haggard line, hoping to see an opportunity to order his men off the field, or to pull them back enough to re-form strong, tight blocks and keep holding. But that was not going to happen. Too many men had died and even in Thomas' short experience, it was obvious that Gremminger's superior numbers would, in time, push through the town and take the field. So what to do? What do I do?

Then he saw a ghost coming down the ridgeline, Captain Goepfert, his banner of a golden shield on a red-and-white field waving carelessly in the air. Thomas blinked, wiped sweat from his face, and looked again. It was no ghost. It was the man in flesh, holding his saber high, mouth open and teeth bared although his battle cry could not be heard from this distance. He was alive and leading a charge. Alive . . .

"Goepfert, you son of a bitch, I'm going to kill you myself."

Without thought, Thomas spurred his horse onto the battlefield. He could not take his eyes off his commander, holding his field glass like a club. If Goepfert were near, he'd knock the lying bastard off his horse with a crack across his skull.

Thomas found himself surrounded by his men, some crawling out of the battle, some falling back with exhaustion, some dumbfounded by the fact that he was among them. He held up his glass like a sword and said, "Don't look at me, you fools. Get in and fight!"

His eyes, however, were fixed on Goepfert, who had turned his charge toward a clump of Spanish halberdiers stubbornly holding the center of the line.

His eyes, however, were fixed on Goepfert, who had turned his charge toward a clump of Spanish halberdiers stubbornly holding the center of the line.

"Goepfert!" Thomas yelled, but his captain did not respond. He either did not hear or did not care to answer.

Thomas' horse stopped abruptly as a pike was thrust into its face. It missed the horse by inches and Thomas grabbed the spear tip to keep it from plunging into the beast's neck. He twisted in the saddle, holding the pike and kicking at the man who tried desperately to knock him from the horse. Thomas, his mind wild with fear, dropped his field glass, drew the Enfield, and aimed it at the head of the enemy pikeman. He pulled the trigger back and was about to fire, when the man's shoulder blew apart, struck by a shot that hit him square in the back. He dropped the pike and fell forward dead into the bloody mud.

The young boy who had fired the musket from behind was shaking violently, clearly terrified by what was going on around him. Thomas was about to say something, but the boy ran off and disappeared into the smoke.

Thomas dropped from his horse and continued on foot, toward the block of Spanish halberdiers. Sweat poured from his face. His heart beat so fast he could barely hear anything around him but the coursing of his own blood through his sweat-soaked body. Everything was like a dream, moving slowly, a shadowy echo of battle in his mind. But it was real, all too real, as he watched Goepfert's charge hit the Spanish block and tear it to pieces. Goepfert was tossed from his horse. Thomas stopped and suddenly he could hear everything, every cry, every crack of bone, every plea for mother, every whinny of a horse, every clash of steel.

"Goepfert!" He ran to his fallen commander. He found him there behind the carcass of a skewered horse, wrestling with a Spaniard. They rolled in the mud, scraping with mad fingers at each other's throats, their eyes dark and furious. Thomas had never seen two people so intent on killing each other. What should I do? He didn't know. But he had a gun in his hands. He held it up and swung it like a club and hit the Spaniard square in the temple. The man went limp and Goepfert pushed him aside.

"Thank you, Thomas," he said, rising and rubbing red, gooey mud off his face. "But you can fire one of those, you know."

"I thought you were dead!"

"Yes, but I'm not."

"I should kill you my—"

Goepfert pushed Thomas aside. "No time for argument. Look!"

He pointed to the town. Thomas turned to look and there, at the edge of Susch, a line of cavalry was charging down the road, thirty strong, led by Gremminger.

The duke's personal guard followed him closely, spread in a wedge that struck the first line of infantry. It did not seem to matter to Gremminger whether he hit his own men or not. It was clear to Thomas that the duke intended to pierce the infantry line and make for the center, where he and Goepfert now stood.

"What do we do?" Goepfert asked.

Thomas shook his head. "I—I don't know. What should we do?"

"You're in command. Lead! Make a decision."

His throat was paralyzed. No thought he could conceive measured up to what needed to be said. The men gathered around him, some on horse, some on foot, a mixture of pike, sword, and gun. All of them with their eyes upon him, waiting for his decision. He felt a mere foot tall, a tiny bauble, shiny and important, but shallow and without substance. In his tent, with dice and maps and blocks, there was substance. Here, there was . . .

"Hold the line!" he yelled, not believing the words that came out of his quivering mouth. "Refuse the field!"

Goepfert barked the order up the line and men hastily fell in place. But Thomas did not hear. He was not a part of it anymore.

He stepped away from his men. Goepfert reached for him but Thomas shrugged him off and moved into Gremminger's path. He held the rifle forward and steady with both hands. The ground shook with the weight of the charge, but Thomas did not move. In his mind, he saw the faces of the two bright and capable young men from Grantville, heard their playful competitive banter and watched them roll their dice. War was just a game to them, something to play on a lazy afternoon to bide time until they reached adulthood and set aside their toys. They did not carry the burden of responsibility like he did, day after day. They did not carry the weight of blood on their hands like he did.

Gremminger drew closer as Thomas waited with gun held forward. The rattle of machine gun fire filled his mind. He was an American soldier again, chopping his way through the jungle, throwing grenades down a tunnel, diving for cover as mortar rounds struck his foxhole. The ground shook. Gremminger drew closer, closer. He could see the duke's large, impetuous grin.

At this short distance, the accuracy and power of the weapon increased dramatically. He'd never fired it before, but he knew. The math was so obvious in his mind.

Thomas raised the gun higher, aimed carefully, and fired.

****

Thomas knelt beside Gremminger's body. The shot had torn through the duke's chest and neck. He'd hit the ground, breaking his back. Tiny bits of clavicle stuck out of his ruined shoulder, and Thomas turned the body over and looked into the man's face. It was bloody and wet, part of it torn away as his body, thrown from his horse, had slid over the hard ground. Thomas closed his eyes. What a mess.

With their leader dead, Gremminger's army had fallen back. The Spanish retreated first, what was left of them, followed by the cavalry and then the remaining pike blocks. One entire unit of Gremminger's infantry had not even made the field. Thank God for that, Thomas thought, as he stood and looked over the broken ground. Bodies lay everywhere, and the citizens of Susch picked their way back home, moving through the carnage, looking for loved ones, lost boys. Mothers cried, daughters and young sons wept. Thomas felt like crying too. He had not anticipated the civilian cost of the battle, hadn't factored it into his combat model. He would do better next time.

"You lied to me, Goepfert," Thomas said, drawing dice from his pocket. "You dictated that note, didn't you? You knew I would have no choice but to come on word of your death. You led me here, and I could have been killed."

Goepfert nodded, his injured arm held tightly at his side, his swollen jaw bandaged. He sounded like he had cloth in his mouth, but he spoke as clearly as he could. "Yes, My Lord, and I apologize for that. If you wish to reprimand me, I'm prepared to face your father. But I hope you understand why I did it. You're a brilliant young man, Thomas, but war is more than mathematics. Those numbers on your blocks represent real flesh and blood. In your heart, I know that you know this, but you must experience it, not as an assistant, but as a man and a commander. Do you understand?"

Thomas rubbed the dice in his hand. He nodded. "Yes, I do." He opened his hand and counted the pips. "I'm not cut out for field command, am I?"

Goepfert sighed and shook his head. "No, you are not. But in time, you could be. You showed great bravery today, if not a little impetuousness there at the end. But you stood your ground and made a decision. You just need to set down those dice and apply yourself."

"Are you nuts?" Thomas said, remembering a famous line from an American general during World War II. He gripped the dice and blew into his fist. "I'm more convinced now than ever that I'm right. My plan worked. It was costly, yes, and I made some mistakes. I didn't put enough emphasis on how a superior force, just by its sheer presence, impacts the overall psychology of the battlefield. I'll do better next time. But we won today. We own the field."

Goepfert nodded. "We own it today, my lord, but tomorrow? I'm not so sure. The Gremminger family will not take this lightly. His daughter will seek vengeance, and what of the Hapsburgs? I dare say we've not heard the last of them."

Numbers passed through Thomas' mind, blocks moved, and dice rolled. "We'll worry about all that tomorrow." He stepped over Gremminger's body and placed his hand on Goepfert's shoulder. "For now, let's regroup and pull back to the security of the Flüelapass. Oh, and find Elsinger and Arnet. I want you all in my tent by sundown."

The captain nodded. "What for?"

Thomas opened his hand and revealed his dice. Box-cars.

He smiled. "I have a plan."

****