"Tell me a story," said one of the twins.

Anar clawed his way out of the past like someone scrambling up a rubble-strewn slope. Here were bits of his childhood at the scrollsmen's college, where he had been happy. Hard to remember, now, how that had felt. Here were the ruins of a beautiful, embroidered coat—Greshan's, probably, that cruel swine. Anar had often wondered about m'lord's childhood with such a brother, how much it might have influenced the man he had become. Here was a scrap of memory, charred at the edges, that still seared: a pyre and at its heart, a small, indomitable woman wrapped in flame.

Oh, Kinzi, and all the women of my house, burning, burning, the taste of their ashes bitter on my lips . . .

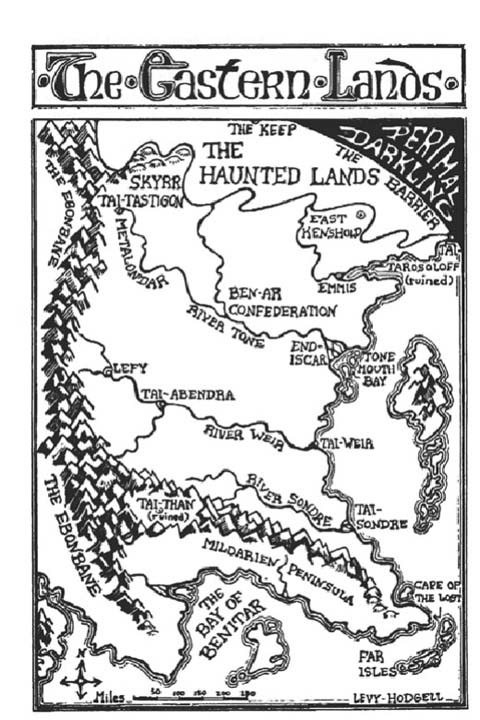

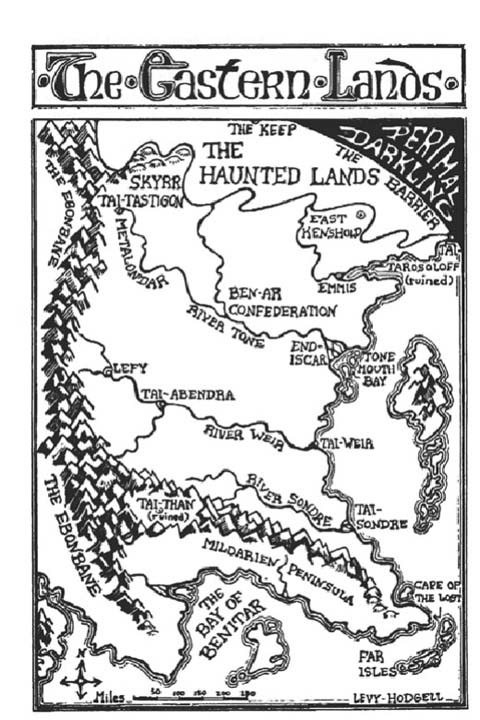

He scrubbed a dirty hand across his mouth and blinked up at the child on the hillcrest above him, dark against the slow, opalescent seethe of the Barrier.

Was it the boy or the girl? When not together, they were hard to tell apart. The same wild black hair, cropped short; the same eyes, storm-gray or silver as light or mood caught them; at seven years old even still much the same build, thin and wiry . . . there was even some confusion as to which had been born first. But one had fingernails and the other, this one, usually hid her hands because she didn't.

The girl Jame perched above the keep's straggly kitchen garden, watching him, waiting.

"A story," she prompted. "Something true."

"Not all stories are," he said absently. "You ask the singers about their precious Lawful Lie." Not that she could: the only singer to go into exile with his lord had been among the first to die.

He stared at the roil behind her of the Barrier that separated this world from the next. Beyond it, shadow folding into shadow, Perimal Darkling waited. That was true enough, ancestors preserve them. So was the Master's House, that nightmare looming out of a fallen past. He could almost distinguish the crooked lines of its many roofs, shifting in the shadows of countless moonless nights, its windows without number opening to the soulless dark within.

Trinity, but it was close. Only once before had it been closer. The garrison had been some three years into its exile then, long enough to see that it would only end in death. The sooner the better, they had thought, and so again followed their lord headlong into hopeless battle, this time against primordial darkness itself.

Death, at last, with honor . . .

Anar shuddered, remembering the slow churn of mist under that cliff of shadow that had confounded and dragged them apart. Only he and two score others had stumbled out. Some, gaunt with hunger, mad with thirst, said that they had been trapped for days, for weeks, in that murky limbo. Some only stared with hollow eyes, mouthing the same words over and over again:

" 'm hungry, 'm hungry . . . "

That had been the garrison's first experience with the haunts that gave this accursed land its name.

It was also when they discovered that their priest, Ishtier, had run off, taking his lord's Kendar mistress and his own priestly powers with him, just when they had most needed a pyric rune to deal with their own walking dead.

Of them all, only the Gray Lord had penetrated the shadows and come at last to the Master's Hall, or so Anar guessed. Where else could he have found that beautiful, nameless lady whom he had brought out with him to grace his bed and bear these children, brother and sister, with so much of her strange magic in the silver shadow of their eyes?

Words whispered in his mind, silken fingers meant to tease out memory like a snarl:

Let no one see . . .

See what? Of whom had he been thinking?

Anar floundered for a moment before the subtle sinews of his patchwork priest-craft steadied him.

He had come to this twisting of the way before—every time, in fact, that he thought or spoke of the twins' mother. Others looked puzzled if he mentioned her, as if she were a fading dream, half or wholly forgotten, a thread of sweet song, a movement of heart-breaking grace limned in moonlight, a fleeting glimpse of glamour.

Let no one see . . .

Only the children remembered, and the randon Winter, who had her own reasons, and the Gray Lord.

Anar felt his breath catch. Somehow, he had forgotten: there was the House, looming, and Lord Grayling had gone again, alone, to storm it, to reclaim the fey bride whom he had somehow lost or perhaps just misplaced. How long had he been gone? Days? Weeks? If he didn't return, what would happen to his people, who had gone into this bitter exile for his sake? Did he even care?

Pushing aside the thought, the scrollsman pulled up something that should have been a carrot. It was the right color, at least, but its tip twitched like a rat's nose and its white rootlets stung his hand. Anar snapped the root in two, ignoring its thin, piping shriek.

"Dare you to dig up a potato," said the child. "All those eyes, blinking. Ugh."

"At least they don't scream," said Anar.

He blinked, remembering the pile of limp vegetables that already lay in the keep's kitchen, some of them still mewling weakly and trying to crawl away. Since m'lord had stormed out, no one had felt like cooking or eating. What a waste. It had taken long, hard work to make the soil of the Haunted Lands yield even this sorry crop. Only the collective will of the garrison continued to make it possible—that, and Anar's own makeshift attempts at priest-craft which, he knew, were slowly unraveling his mind.

"I don't think you're mad," said the child, judiciously, "or at least not as mad as Tigon. He keeps trying to eat his own toes."

Sweet Trinity, he must have been thinking out loud again.

"Yes," said the child, "you are, off and on. What does 'fey' mean?"

Don't think. Talk.

"A story," he gabbled. "You asked for a story."

But what story could he safely tell? M'lord had forbidden him even to teach these children their father's true name. Someday, he might inform his son and heir, Torisen, but never this fey, unwanted daughter, already too like her mother for comfort.

"That word again. 'Fey.' Is that why Father doesn't like me?"

Shut up and talk.

"Suppose," Anar said, desperately launching himself, "that there is a land where the animate and inanimate, the living and the dead, don't overlap."

"You can always tell them apart?"

"Yes. No. Most of the time. Suppose the lord of that land came home one day to find all the women of his family slaughtered."

"They didn't turn into haunts?"

"No. He had a priest speak the pyric rune and they all burned up. Crackle, crackle."

"Who killed them?"

"This lord had many enemies, but he thought he knew whom to blame and he set out to punish them."

Anar shivered, remembering the Highlord's rage as he turned from his grandmother Kinzi's pyre, his berserker madness that had infected them all.

"Did he make them pay?" asked Kinzi's great-granddaughter.

"No. He guessed wrong. I think. Anyway, there was a big fight and a lot of his own people got killed. After that, they didn't want him to lead them anymore, so they drove him away."

Why was he telling this of all stories? M'lord would kill him! Belatedly, Anar shoved half the carrot into his mouth to silence himself. The rootlets writhed and stung as he bit down.

Let me not speak . . .

"What happened to him? How does the story end?"

"I don't know." The words were slurred, his mouth already swelling. "So far, it hasn't."

The child waited to see if he would say anything more or, perhaps, fall over dead. When he did neither, only flapping a hand helplessly at her in dismissal, she jumped up and ran away.

THE HILLS of the Haunted Lands seemed to roll on forever, under a rolling sky. Jame ran down through the coarse, clinging grass and up, down and up, jumping off the crests, trying to fly.

From a rise, she saw the squat tower of the keep, dark against the Barrier except where the crystal dome over the lord's solar caught the evening light. The sun was going down to the west; to the east, a gibbous moon slowly climbed the sky. A fitful, sour wind from the north ruffled her hair and combed the grass over her toes.

Turning southward, Jame plunged down again; then, more slowly, she climbed. Beyond, she could hear Winter grunting instructions:

"Here. Aim. The foot, so. Your shoulders . . . turn them into the strike. Better."

Jame dropped to her stomach and wriggled up to the hilltop. Through a fringe of grass she watched as their former wet-nurse taught her brother a fire-leaping move of the Senethar.

Winter, a big, raw-boned Kendar, towered over her young student, holding a large hand higher and higher to make him extend his kick. Scowling with concentration, Tori pivoted and struck. His bare foot slapped against her palm.

"Good," she grunted, and hooked his other foot out from under him. "Not so good."

Tori had landed on his back without adequately breaking his fall. The rock-hard ground smacked the air out of him and for a moment he lay there gasping.

"Up," said Winter. "Again."

Jame watched, idly plucking stems of grass and letting them snake through her hair. They wriggled and tickled as they tried to take root in her scalp. She thought they camouflaged her nicely, until Winter turned her long, horse-face up toward her.

"Come down," she said; and then, to Tori, "Enough for today. Practice that."

Jame clambered to her feet and skidded down the hill. Half way to the bottom, she launched herself at Winter, but the Kendar simply caught her in mid-air. The randon's hands completely encircled the girl's waist.

"Too thin," she grunted, swinging Jame around and setting her down beside her brother. "Eat more."

"Oh, Winnie, please teach me how to fight too!"

"She can't," said Tori, brushing dust off his much-patched backside. "You're a girl."

"So is Winnie."

"Was," said the Kendar, and knelt to put away the practice weapons. "A long time ago. You," she glanced at Jame, "are not a girl. You are a lady. It shames us all that m'lord will not let us treat you accordingly. Still, I would teach you too, if your father had not forbidden it."

"That's unfair!"

"Much is. Accept it."

"Anyway," Jame said to Tori, "while you were busy falling on your butt, I got Anar to tell me a story, all about a lord who got kicked out by his own people. So there."

Winter glanced over a shoulder at her. "So. The scrollsman has told you about the White Hills. Interesting. And about time."

Anar hadn't mentioned the White Hills. "Were you there?" Jame asked, probing for more.

Winter bound up the sword case. "Yes," she said, without turning. "Sere was too. He came at me in battle with the Highlord's madness in his eyes, and I killed him for the sake of our unborn child."

"You had a baby?" Tori asked. "What happened to it?"

"He was born here in the Haunted Lands, and here he died."

"How?"

Winter sat back on her heels, still not facing them. "Your mother had no milk. I was still nursing Tob, there being nothing fit in this accursed land to feed a child. Besides, he was . . . slow. Even then, two nurslings I could have managed. Not three."

The twins waited. They both knew which two Father would have chosen.

"Your mother was so beautiful. Tob ran to her, and I let her hold him. In her arms, his soul left him. I . . . dealt with what was left. It was the only time I ever saw her cry except for once more, when she gave you into my charge."

The twins looked at each other. Jame asked for them both: "Do you still love us?"

At last the Kendar turned. "Of course," she said. "You were my nurslings."

Jame collared her by the leg. Winter ruffled her hair, plucked out the wriggling grass, and tossed it into a patch of snap-weed where it was immediately torn to pieces.

"Now go." She tipped up the child's chin to regard a fading bruise. "Stay close to the keep, but away from m'lord if . . . when he returns."

The twins ran off, chasing each other turn and turn about over the swooping hills. Jame pounced her brother, catching him off guard and in the face with her elbow. He yelped in pain. They rolled down the slope, scrabbling like puppies. At the bottom, she broke free, dashed up, and threw herself down on the crest. Tori joined her, wiping a bloody nose on his sleeve.

"Why did you do that?"

"Winnie told you to Practice. Besides, I wanted to see how you would block the blow. You didn't. I was trying to learn something."

"Father says it's dangerous to teach you anything. Will the things you learn always hurt people?"

She considered this. "Maybe. As long as I learn, does it matter?"

He snuffled loudly and wiped his nose again. "It does to me. I'm always the one who gets hurt. Father says you're dangerous. He says you'll destroy me."

"That's silly. I love you."

"Father says destruction begins with love. Anyway, you did hurt me."

"Crybaby."

"Little girl."

"Daddy's favorite."

"Freak."

She hid her hands in her armpits but drew them out again almost immediately to gnaw on her nail-less fingertips. "They itch," she said, defensively. "I hate them. When I grow up, I'm going to have a different pair of gloves for every day in the week. Winnie's child . . . d'you think he was the third? Remember? We used to dream that there were three of us. We used," she added wistfully, "to have the same dreams."

"We were children then," he said, not meeting her eyes. "I don't dream anymore. Much."

Father beat him when he did. Somehow father always knew.

"Shanir's dream, boy. Are you a filthy Shanir?"

After that, Tori had begun to sleep less and less, often keeping his sister awake with him. For the last two nights, neither of them had slept at all.

They rested now, watching the Barrier. The setting sun cast rays of light slantwise across it, veiling what lay within, but a low, continuous rumble betrayed its presence. Snake-tongues of lightning flickered back in the dark.

"Father is still out there, looking for Mother," said Tori, "but two nights ago she left footprints in the dust beside our bed. That's proof. She is still here."

"I know. Last night she must have been dancing through the death banners in the hall. You know the one with the man with the wart on his nose? Well, you can't see it now, the wart or the nose. He turned around to watch her."

"She shouldn't hide from us," said Tori, tearing grass with his fingers, ignoring a tiny chorus of cries. "Father has a right to her. So do we. She belongs to us, doesn't she?" When his sister didn't reply, he repeated fiercely, "Well, doesn't she?"

"I . . . don't know where she belongs." Jame gave him a sudden push and sprang to her feet, away from his angry eyes and bewildered pain. "I know: hide-and-seek. You be Father, I'll be Mother. Catch me if you can!"

And she was off, plunging down the hillside in a swirl of flying hair, thin legs, and tattered rags, running headlong toward the keep.

THE GREY HORSE stumbled, its gaunt sides foam-flecked and heaving, black with sweat. The grass of the Haunted Lands had proved treacherous fodder and this, Ganth's war-horse, was the last of the garrison's mounts. He gouged its flanks again with cruel spurs, ignoring the rattle of its breath and his own parched, aching throat. He would win through these shifting veils of light and shadow. The House loomed before him, no closer than it had been an hour, a day, a lifetime ago, but he would lay his white bones on this endless bleak moor before he gave up.

"Gerridon!" he howled at that bleak filmy facade. "I have come for my lady. Return her to me!"

The stallion shied, stumbled, and fell. Ganth Gray Lord rolled to his feet. Wavering shafts of light fell through the Barrier as if through dark water onto the matted turf, a world in shifting shades of gray.

A black-clad figure had emerged from the long shadow of the House. Under its hood, its face shifted. One corner of the mouth hitched up nearly to a hidden eyebrow in a lopsided smile, then quivered nearly straight again.

"Believe me, Grayling, my blood wouldn't agree with that blade."

Ganth's hand dropped from Kin-Slayer's hilt. "No, not Gerridon. Keral, his faithful dog. Where is your master?"

The changer glanced over his shoulder at the House. A continual rumble came from it, stone on stone, as if, at a glacial pace, it was grinding forward. Silent lightning played across its many angles. "He is coming, room by room, out of the depths of the House, but not to meet you. Dead or alive, you will never stand in my lord's hall again."

"Where is my lady? Where is the Dream-Weaver?"

The mask of rage cracked. A desperate boy stared through the ruins of a disastrous middle age.

"P-please! Ever since that night in the death-banner hall at Gothregor, awake or asleep, no one else has seemed real to me and nothing else has mattered. If I had ever dreamed that she was here, waiting . . . "

"She wasn't. Not for you." The other's face changed again, settling into Greshan's handsome, heavy lines. "Gander, Gangoid, Gangray, you silly little man. Twenty years ago, you were nothing. So you became highlord. So what? All you accomplished was to get your womenfolk slaughtered while you were out hunting—yes, even your precious Gran Kinzi. Whose name d'you suppose she cried before the knife cut it short?"

"Don't!" Ganth covered his ears. "I didn't hear then; I won't listen now!"

"Evidently."

Greshan's face warped back into the changer's feral grin. "Still, it was the massacre of the Knorth women that brought your need in line with my master's: his sister-consort for you, a child of her blood for him. He would have reclaimed both her and her get sooner except that time in the House passes so oddly, now fast, now slow, that even Gerridon sometimes misjudges it."

"Her'get." Ganth made an impatient gesture, sweeping his children aside. "Compared to her, what are they?"

Keral blinked. "What, more than one? Not . . . twins? Damn. I warned my lord that he should be more specific in his contract, but he brushed me off. 'My lady knows my will.' Huh. Perhaps he didn't know hers."

The changer began to pace back and forth in the shadow of the House, thinking out-loud.

"Twins. But then so were Gerridon and Jamethiel, incomplete, unbalanced by the missing third. Surely, by now, the time for the Tyr-ridan has passed and the three faces of God will never meet. From the start, it was a false promise, made by a false god. What my lord began with his so-called Fall, he will finish, and all of us who chose the winning side will have our reward. But first . . . " He stopped. "At least one of the twins is a girl, yes?"

"Yes. She bears her mother's name. From the first, I saw Jamethiel in her eyes, but the way she looks at me now . . . " Ganth shuddered and cradled his bandaged hand. Dried blood stained the cloth over his knuckles.

"What did you do?"

"N-nothing!"

"Oh, but you wanted to, didn't you? The taint is in the blood, and the attraction. Remember your brother Greshan? What he did to you . . . admit: some part of you enjoyed it. You Knorth. You come together like sparks in a holocaust and consume each other. And now you also have a son. Tell me, Gangrene, have you taught him yet how to play the midnight game?"

He slipped out of the way as Ganth lunged for him, tripping the Knorth as he passed. "Now, now, temper. Or was Gerraint right?" His face shifted. Ganth's father drew himself up and glared down at his son. "Trinity," he said in that well-remembered voice, with freezing scorn. "Another god-cursed Knorth berserker."

"I am n-n-not!"

"Then control yourself, boy. These aren't the White Hills, and you have a son to consider. Ah, that poor, little tyke. Thanks to you, what is left for him to inherit?"

Ganth rose. His eyes smoldered silver in a white, haggard face. The shadows of the land rose with him, drawn up by the strength of his sudden, cold rage.

"What will Torisen inherit? My vengeance against those who brought me to this end and our house to such ruins. Trinity, why didn't I see it before?"

In his turn, he began to pace. The changer matched him step for step, up and down in the long shadow of the House, his half-hidden face slyly mocking the other's rage and despair.

"The slaughter of my kinswomen at Gothregor, the debacle in the White Hills, both were conceived within the Kencyrath itself, and by whom but the filthy Shanir?"

"Tsk, tsk, jumping to conclusions again, but then we all did regarding your womenfolk. As it turns out, one survived."

Ganth stopped short, staring. "What?"

"Oh yes. A child. The child, in fact, for whom my master holds a contract duly sealed by your father, for your sister Tieri."

"Liar!"

The darkling's eyes glinted dangerously. "Ah, be careful whom you insult. The reckoning between us may be slow in coming, yet it will come."

"I would have known if any of my blood still lived!"

"Would you? How? In the White Hills you threw down your name as well as your title and stormed off into a self-imposed exile. You say they forced you? Did you fight them? No. You had to make your grand gesture. They must love you, obey you without question, or Perimal take them all. Such is the Highlord's due. My master felt much the same. What did the Kencyrath, your house, or your blood matter to you then?"

"To be fair, I only just learned about Tieri myself." Keral laughed in rueful admiration. "That clever Ardeth matriarch, hiding the brat for all these years, right there at Gothregor in the Ghost Walks. That's what they call your former quarters, you know."

"Ardeth. A house rotten with Shanir. I should have known."

"Then know this too. You have come for 'your' lady? She was barely yours even when you held her in your arms. Do you think she loved you? Do you think you were even real to her? The tighter you tried to hold her, the more she slipped away, into dreams and nightmares, into the layers of that rotting keep where you choose to fester in the ruins of your life. Let her go."

"I can't!"

"I know. Poor, lost, little boy. Then go back, Grayling, as fast as you can. Though you couldn't find her before, she is still there, waiting for her master's call; and here you are, hunting again in the wrong place."

Ganth stared at him aghast, his rage forgotten. "Still there?"

"Oh yes, but not for long. A day, an hour, a minute before you arrive . . . then gone, forever. Think about it."

The Gray Lord looked wildly about for his mount. It had regained its feet and stood watching him, unblinking. If it no longer breathed, he didn't notice. He sprang onto the haunt that had been his war-horse and set spurs to it.

Keral watched him go, smiling to himself. Then he turned. The doors of the House swung open to admit him.

FOLLOWING HER SUNSET SHADOW, Jame trotted across the stone bridge, through the gatehouse, into the keep's circular courtyard. She hoped that Tori would follow, that he was only giving her a fair head start. Playing hide-and-seek alone wasn't much fun. Recently, a lot of other things hadn't been either, but she kept hoping. Sooner or later, something interesting was bound to happen.

Now, where should she hide?

Small, stone chambers lined the courtyard, their backs to the outer wall. Some were domestic offices—a forge, an armory, a kitchen full of raw, wilting vegetables, a bakehouse, its oven days cold, a privy . . .

No, all too obvious.

Then there were the garrison's barracks.

Kendar sat listlessly outside on benches or lay out of sight within on their narrow pallets. They still looked and acted as if Father had cracked them on the head with a board on his stormy way out. Only Anar and randon like Winter seemed to have kept their wits. Jame wasn't quite sure about Tigon. The common Kendar were usually kind to her—when Father wasn't in a rage. Then they couldn't seem to help themselves. She slowed, feeling their leaden eyes on her. As she passed, some muttered words in a hoarse, familiar voice not their own:

"Another god-cursed berserker . . . filthy, filthy, rotten Shanir . . . "

But she wasn't Shanir, Jame told herself, balling up her fists in the pockets of her cut-down but still too-large shirt. She was only a freak with no nails and itching fingertips that drove her half crazy. Surely there were worse things than that.

Like hunger.

Right now, even a raw, near-sighted potato sounded good. It was another smell, though, that made the child's stomach growl, even though she couldn't identify it. The garrison, perforce, ate only overcooked vegetables, boiled grains, and stewed grass. This was something different. Jame followed her nose up the stairs to the tower's first-story entrance.

Tigon crouched over a small fire set between the inner and outer doors, cooking something. He tilted his broad, scarred face to grin up at the child as she stopped beside him. "I finally caught the little buggers." He plucked a nugget-shaped object out of the fire and popped it into his mouth. "D'you want one, lass?" he asked indistinctly as he chewed. An ecstatic expression lit up his battered face. "I have three left."

"No thank you, Tig." She regarded the randon's bloody, nearly toeless feet dubiously. "Will they grow back?"

"I hope so. All those damned, stewed weeds . . . " He spat out a small bone and smacked his lips. "Ah, you poor younglings. You don't know what you're missing."

A mutter rose from the courtyard, the words disjointed at first but each speaker slowly picking up the cadence:

"He is coming. He is coming. He is coming . . . "

"About bloody time," said Tigon. He wiped greasy hands on his jacket, rose, and lurched against the wall with a grunt of pain. Jame grabbed his belt to steady him. "Thank ye, lass. Not to worry. It only hurts when I stand, and worth every damned toenail." He glanced down at her bruised face. "Here now, you'd better make yourself scarce."

With his shovel of a hand, he scooped her into the hall and closed the door firmly behind her.

Well, she thought, standing in the sudden gloom, that was interesting, but not especially pleasant.

She began to wander about the circular hall, absently gnawing on her fingertips, feeling lonely and cut off from the growing commotion outside as the Kendar woke from their daze. Tori hadn't followed her, either. Father says, Father says . . . the more Father said, the farther Tori drifted away from her. It was like slowly losing sensation in an arm or a leg, except this was in her mind. The same thing had happened with Mother.

She paused in front of the worn death banner where the man with the warty nose had glowered out at the hall for as long as she could remember. Yesterday, he had shown only his back. Today, he was gone, leaving bare warp threads. The same thing had happened to banners all around the hall. Was she the only one who noticed? Well, they had been very, very old, nameless and dead long before her time. Her family must have lived here forever, although, oddly, none of the worn, woven faces in the hall had looked anything like Father, Mother, or anyone else she had ever known.

Another mystery.

Like Mother.

She was fading away too, only it had taken years, and she wasn't quite gone yet. Jame considered this. She didn't exactly miss her mother, since she hardly knew her. Besides, there was Winter. Tori seemed to feel her absence more strongly than Jame did—unless, again, that was Father's influence. Jame wished she could help Father. She had tried, but the very sight of her seemed to enrage him. Her hand stole up to her bruised cheek.

She knew she shouldn't have gone into the master chamber under the cracked, crystal dome, where her parents had lived in the brief time they had been together. She and Tori had been conceived and born in that big, ramshackle bed—the only one, in fact, in the entire keep.

Other bits of unique furniture included a small table heaped with bottles of dried up cosmetics and a large, dim mirror. Tapestries lined the windowless walls. In repairing them, the Kendar had added their own faces to the host of people who marched across their threadbare plains, as if to say Consider us, too, among the dead. Anar was there, and Tigon, and Winter, holding an empty-eyed child whom Jame now realized must be Tob.

Mother had seldom left this room, and Father still kept it ready for her return. He had forbidden anyone else to enter it.

Hard, though, to keep out a curious child.

When Jame had found the garland of flowers on the bed, it hadn't occurred to her that they were another present from Father to Mother, trying to win her back. True, they stank somewhat as all blossoms did in the Haunted Lands and twitched when she picked them up, but he must have searched long and hard to find them. Jame had only thought that they were pretty and had put them on over her own wild, black locks. Peering into the mirror, she had wondered Is this what a lady looks like? and pulled a face at her reflection. Then it had seemed only natural to go down to the hall and dance for the warty man who must, surely, have a very dull time of it hanging there on the wall, what with his ugly warts and all.

At first, she hadn't seen Father watching her. Then his husky voice had stopped her in mid-step.

"You've come back to me," he said. He looked half dazed with a relief so intense that it wiped twenty years off his face. "Oh, I knew you would. I knew . . . " But as he stepped hastily forward and saw her more clearly, the softness ran out of his expression like melting wax. "You."

Before she could move, he struck her hard across the face, slammed her back against the wall and pinned her there. She could feel his whole body shake. Before, she had been wary of him. Now she was terrified. "You changeling, you impostor, how dare you be so much like her? How dare you! And yet, and yet, you are . . . so like."

His hands rose as if by themselves to cup her bruised face. She stared up at him, hardly knowing what frightened her but very much afraid.

"So like . . . " he breathed, and kissed her, hard, on the mouth.

"My lord!" Winter stood in the hall doorway.

He drew back with a gasp. "No. No! I am not my brother!" And he smashed his fist into the stonewall next to Jame's head.

Now she touched the dry spatter of his blood, remembering how he had stormed out that day, shouting for his horse and his sword. He was going to reclaim his love, alone, and he would kill anyone who got in his way.

Winter had knelt beside her. "All right, child?" Jame remembered nodding, and not being able to stop until the randon touched her shoulder. Then Winter had risen but paused, briefly, looking down at her. "It isn't entirely his fault," she had said, and gone out to ready her lord's gaunt gray stallion before someone got killed.

If not his fault, Jame wondered now, then whose? Perhaps she was to blame for having taken those flowers. She sensed, however, that it also had something to do with love.

That was where destruction began, according to Father. Was this how it ended, with speckles of dried blood on a stone wall? If so, she would do without it, except for Winter. And Tori. Whether he liked it or not, she would go on loving her brother—even if, right now, she felt more like hitting him.

"If I want, I will love," she told the empty hall. Her words became a chant, her small, bare feet stomping in time to it:

"If I want, I will learn.

"If I want, I will fight.

"If I want, I will live.

"And I want.

"And I will."

She was dancing now, a scarecrow of a girl, but with a grace and strength of which she was barely aware bred into her very bones. She followed the movements she had seen Winter teach Tori, the fighting kantirs of the Senethar, shaped to the defiance of her mood. Bend, turn, strike . . . ha!

Someone danced with her.

At first, Jame didn't notice. Then, out of the corner of her eye, she caught a pale glimmer, gone when directly faced, or rather shifting again to the side, just out of sight. It moved with her or she with it, mirroring each other in reverse. Her own movements grew more fluid and sure. Wonderful. Intoxicating. She lost herself in them, and found that she was dancing with her mother.

They circled, the fey child and the lovely woman with her dream-lost smile. Jamethiel's white gown and long black hair flowed around them. Her slender hands caressed the air so close that Jame felt their warmth on her face. She wanted to lean into them, to feel a mother's touch that she only remembered in dreams, but they glided away.

Dangerous, dangerous, murmured the air.

But why?

The hall shifted subtly around them, and shifted again. The faces were back against the walls, watching from their banners. No. They were drifting ghost-like in and out of the webs of their own deaths, sometimes turning to look, puzzled, sometimes turning away with a frown. This had all happened long ago, Jame realized. The years eddied and flowed while Mother sang softly to herself, to her daughter, unaware that her very presence frayed the souls around her. This was where she had been all this time, wreaking ruin in the keep's past without even noticing. No wonder Father couldn't find her.

Outside, hooves rang on the flagstone amid warning cries: "Haunt!"

"Catch it!"

"Shut the gate!"

"Too late."

Then Father hammered on the hall door, demanding to be let in.

Silly, thought Jame. It isn't even locked.

But that all seemed far away and unimportant. She danced on, lost in her mother's smile.

Somehow, they were upstairs now, in the forbidden chamber under the crystal dome. Jame couldn't see her own reflection in the big mirror, but she could see Jamethiel within its clouded surface, dancing in a dark, vast hall over a floor veined with glowing green. A shrouded figure waited for her. They circled each other, almost but not quite touching, in the ghost of an embrace. Then she danced on, deeper into the mirror, farther and farther away.

Only then did Jame realize that she was alone, in an empty room, in a bleak keep, in the heart of a haunted, hopeless wasteland. Among the dead.

The shadowy man held out his hand to her. She understood that he was offering her everything that she had been denied by Father: knowledge, power, and perhaps even love. And there was Mother—lost, found, and now about to be lost again forever. Jame touched the mirror. Her hand passed through it into cold air. He reached for her.

"Found you!" Tori bounded into the room. "That was the best game of 'seek' ever. If Father finds you in here again, though, he'll kill you."

Then he saw the mirror, and his jaw dropped.

Jame snatched back her hand.

"Don't!" she said sharply to her brother, grabbing his arm. Instinct told her that it would be fatal for him, the wrong twin, to enter that dark hall.

He stared past her into the shadowy, silvered depths. "But it's Mother! She's come back to us! I knew she would, I knew . . . " His voice faltered. "No, she's slipping away again. Let me go! I have to stop her!"

He reached for the mirror.

Jame hit him.

He turned on her, more astonished than hurt, and then furious. "Don't you understand? If Mother comes back, Father will leave us alone. If she doesn't, sooner or later he's going to kill us!"

" 'Destruction begins with love'?"

"Yes! Now let me go!"

She wouldn't. In a moment, they were fighting in earnest, back and forth across the room. Tori's nose began to bleed again. So did Jame's lip when he split it against her teeth with a fire-leaping kick. In doing so, however, he over-extended. She caught his foot and tipped him backward onto the bed. Its worm-eaten legs collapsed. With a soft explosion of dust and feathers from an ancient mattress, the whole structure fell in on itself.

An inhaled feather set Jame to coughing helplessly. This wouldn't do; she had to rescue Tori. She was groping forward when a hand closed on her collar and jerked her back.

"What in Perimal's Name d'you think you're doing?" growled her father.

Then through the settling cloud he saw the ruined bed, with his son's legs sticking out of it. He tossed Jame aside, waded into the sea of feathers, and heaved the footboard off Tori. It had fallen on the boy's head, stunning him and further bloodying his face. He looked terrible.

Ganth turned on his daughter. "You little bitch! What have you done?"

Then, looking past her, he saw the mirror. Dust had dulled its surface, but something moved within it like a distant star. Hastily wiping the glass with his sleeve, he saw a blurred image of the Master's hall. A pale figure danced in it. His breath condensed on the cold surface and again, frantically, he wiped it away.

"Give her back!" he shouted, and struck the mirror with his fist.

"Now, now. Don't break the glass." The words, as distorted as the image, came from within. The figure had minced closer. Draped, loose skin instead of the white gown, flesh that shifted uncertainly between male and female—the changer Keral grinned and preened, naked, inside the mirror.

"Too late, Grayling. The Mistress is back where she belongs, with us, and here she will stay. You missed her by about ten minutes."

Ganth made a strangling sound. Then he grabbed Jame by the arm and jerked her forward, ignoring her stifled cry of pain. "You want the girl? Here. An exchange."

"Too late. My master has reconsidered. This child is too . . . unmanageable. Look at her! Can you see her ever taking the Dream-Weaver's place? Besides, she has shown none of the Shanir traits that my master requires. His gifts would be wasted on her. And now he has an alternative: a pureblooded Knorth child by your sister Tieri."

"Tieri has no child!"

"Not yet, but soon."

The scene in the mirror changed to a blur of white flowers and a sad young woman walking among them. A shadow fell across her and she turned.

"Tonight, in the Moon Garden, the contract that your father made so long ago with my lord Gerridon will at last be fulfilled."

With a terrible cry, Ganth shattered the mirror and ground its pieces to dust beneath his feet. Then he turned on Jame.

"You! This is all your fault!"

She recoiled, sure that he meant to kill her. She couldn't fight him; he was too strong, and beyond reason with frustrated rage. She had to escape, but where was the door? Tapestries covered every wall, all those mute, familiar faces, watching.

She bent over her brother and shook him. "Tori, wake up! Help me!"

The boy groaned but didn't open his eyes. Maybe the falling board had cracked his skull. "This is all your fault," he muttered, almost in his father's voice. Then a singular smile lifted one corner of his mouth. "Why, child," he said, and this time Keral spoke through him. "Didn't you know? Daddy is a monster."

She had paused too long: Ganth's powerful arm circled her throat from behind and jerked her up, off her feet. She kicked backward, without effect, and tore at his arm. Cloth ripped. He swore and dropped her. She scuttled out of reach, stopped, and stared, first at his shredded, bloody sleeve, then at her own no longer nail-less fingers. The itching tips had split open and peeled back. As she flexed them, appalled, sharp ivory claws slick with her own blood slid in and out, in and out.

"Shanir," he breathed, and the word was a curse. "A filthy, god-cursed Shanir. I should have known."

"No!" she said, holding out her hands as if to disown them. "I can't be!" She would chop off her fingers, she thought wildly, as Tigon had his toes, or trim them back to the quick. Anything . . . but too late: Father had seen.

He came after her, with Kin-Slayer unsheathed.

Jame retreated, crying, "Anar, Tig, Winter, help!" But none of them were here, except in their woven images.

She ripped down a tapestry, looking frantically for the door. The weaving fell over her pursuer in a cloud of dust. Swathed and stumbling in its heavy folds, clutched as if by hands of knotted thread, he hacked at the familiar faces.

"Traitors! How dare you try to shield her?"

Jame had her hands on the panel that depicted Winter, Tob, and a big man behind them whom she supposed must be Sere, Winter's long-dead mate. There behind it, at last, was the open door. Through it came Winter herself.

"Traitor!" screamed Ganth again, and cut her down.

Jame tried to support the randon as she sagged, but she was too heavy. "Winnie! Are you all right?"

Clearly, Winter was not. Ashen-faced, she clutched her lower abdomen, but even such strong hands as hers could not stern the tide of blood. Already, the floor was black with it.

Ganth lurched against the wall as if his own legs had failed him. He looked almost as stricken as the randon. "Oh my God. First Sere, then Tob, and now you. Oh, Winter. Ancestors forgive me."

He refocused on Jame who crouched before her mentor, trying futilely to staunch that terrible wound. She turned, nails out, prepared like some small wild creature to defend a loved one to the death, and would have gone for her father's throat if Winter hadn't gripped her arm.

"Run," she said to Jame. "D'you hear me, child? Run." Then, "My lord, you are still . . . not your brother . . . "

Her voice faded. She slumped sideways, hands dropping limply to the floor, coils of intestines spilling over them. Kin-Slayer had cut her nearly in half.

"You!"

Ganth's berserker flare seemed to pick Jame up and throw her out of the room. She ran with no thought except to escape—down the stairs, through the hall, out of the keep, into the Haunted Lands. Collapsing on a hillside, gasping for breath, she still heard echoes of the raging curse that had driven her out:

"Shanir, god-spawn, unclean, unclean . . . "

She stared at her . . . nails? Claws? Her hands were still covered with Winter's blood, as was her face with her own from the lip that Tori had split. At some point, it had begun to throb. Her fingertips hurt too. She clenched her fists to hide the nails, driving them into her palms. The more they hurt, perhaps, the less empty she would feel.

Unclean, unclean . . .

Tori had let this happen. No. What could he have done, even if he had been conscious? But would he try to follow her this time? Not against Father's will. No one would.

Night had fallen, and a cold wind blew. The grasses sang or moaned or sobbed, according to their kind. Haunts would soon be abroad. She couldn't stay here, and she couldn't go home. She had no home, not anymore.

Something large, pale, and ungainly sailed across the face of the moon. That was odd: nothing flew this deep in the Haunted Lands unless, perhaps, it had come from beyond the Barrier.

Watching it, Jame didn't at first notice the vibration in the earth. Then the moon vanished, eclipsed by Ganth's war-horse as it roared over the hill's crest, over her head, nearly clipping her with its steel-shod feet. Its saddle was empty. It swerved, red-rimmed nostrils flaring as it caught her scent. Jame had seen haunts before. They were always hungry, but not for grass.

Something pallid swooped down onto its back. It shrieked with rage and bolted. They plunged past, first one way, then the other, the haunt bucking, the rider groping for reins and flying stirrups. They disappeared over a rise. Jame waited, crouched close to the ground. No good trying to run or hide: with the haunt's keen senses, this was one game of "seek" she couldn't win.

And here they came, trotting back, the stallion in sullen acceptance, the rider tucking in the loose flaps of skin that had previously allowed him to fly. He grinned down at her.

"Well, well. I come to fetch my master one prize and find, perhaps, another. So you are Shanir after all, girl. I smell it on you. Perhaps my master cast you aside too quickly. In any event, it would be wise to make provisions in case his plan tonight fails. Would you like to come back with me to his House?"

Jame stood up, fighting the urge either to hide her nails or to use them.

"You said he didn't want me, that his gifts would be wasted on me."

"Maybe. In that case, we can always feed you to his new war-horse."

"Otherwise, he will teach me?"

"Oh, all manner of wonderful things." He extended his hand. "Well?"

As Jame hesitated, into her mind came the defiant words she had chanted to the keep's blank walls which even the dead had abandoned:

"If I want, I will learn .

"If I want, I will fight.

"If I want, I will live.

"And I want.

"And I will."

She took the changer's hand.

"Home, then," he said, pulling her up behind him.

Changer, haunt, and child cantered off together toward the Barrier, into the shadow of Perimal Darkling.