Johann Bach left his rooming house in the sprawling exurb to the west of the Magdeburg city walls. He nodded to old Pieter the porter as he hurried down the wooden steps and stepped onto the graveled road that ran through the built-up area that by now was several times larger than the city proper. Magdeburg itself, the area within the walls, covered only about a square mile. The arc of land around the walls, beginning with the Navy Yard to the north of the city and ending with the refinery and chemical complex to the south was full of new construction, much of it in raw lumber.

The rebuilding of Magdeburg after the almost total destruction of the city by Tilly's troops and the subsequent withdrawal of Pappenheim's occupation forces had drawn workers and their families from all over the Protestant territories. The eruption of manufacturing concerns that sprouted from the intersection of up-time knowledge, down-time skills and interests, and the support of Emperor Gustavus Adolphus turned a stream of workers into a flood, and much of their initial labor went into raising the buildings they now lived in outside the city.

He stopped at a bakery on the corner and purchased a roll for breakfast. Fresh and crusty it was, and he devoured it with gusto as he walked toward the city walls in the early morning light.

The bridge over the moat was busy with traffic today, as it was most days. Johann joined the stream of men heading into the city. He looked down from the peak of the bridge and watched the water boil around the columns that supported the span. The gates into the city were open, as they were most of the time these days. Magdeburg was a city that was beginning to never sleep.

Johann stepped through the gates, and immediately felt closed in by the walls. It was funny; he never would have felt that way even six months ago. Walled cities and towns was the way things were everywhere; it was the way things were done. But having lived in the "Boomtown," as the up-timers called the exurb outside the walls, now for several weeks, and mixing with the up-timers on a frequent basis and hearing them complain about how crowded and cramped the old city was, he had started to absorb some of their attitudes. He shrugged his shoulders, and hurried on down the street. He had finally found a whitesmith who was rumored to have the knowledge he needed, and he wanted to speak with the man soon.

"Johann!"

He stopped and looked around. He was one of several men doing so, and he wasn't surprised at that. His name was one of the more common men's names among Germans. Sometimes he wished his parents had used a little more originality in selecting his name. They did so with his brothers, Christoph and Heinrich, after all.

"Johann!" the voice called again, and he saw Marla Linder waving at him, two other women at her side. He waved back and walked to meet them.

"When did you get back from Grantville?" Marla asked.

"Wednesday."

"And today's Friday, so you've been back for two days and you didn't let us know." Marla shook her head. "What are we going to do with you?"

Johann grinned and shrugged.

"So, what did you find out?" Marla lifted an eyebrow.

Johann sobered. "I heard many of the recordings, and you are right. Johann Sebastian Bach is truly a great composer and musician, whatever his relationship to my family might be."

"And?" Marla looked at him expectantly. "Did you listen to the one I told you to?"

A slow smile crossed Johann's face. "The Toccata and Fugue in D minor? Oh, yes," he said with reverence. "Many times. One of the reasons I was so long in returning was I was copying it out from the printed copy in the library of your Methodist church."

"Hah. I forgot they had one," Marla replied. "Gonna learn to play it, are you?"

"A silly question, Frau Marla. It may take a while, of course. I share a name with the man, but I am not at all sure I share his talent." Johann grimaced a bit.

"So what's next for you?"

"Organ design and building. In fact, I am on my way to meet with a whitesmith. There is one in Grantville, but I would rather work with one here in Magdeburg. It will make testing and tuning easier. We have a lot of pipes to build."

"How many pipes in a pipe organ?" one of the other women asked.

"I'm sorry," Marla interjected, "I haven't introduced you. Anastasia Matowski," she pointed to the woman who had spoken. She was very short, petite, slender, with a long neck that lifted her head above her collar. "And this is Casey Stevenson," Marla pointed to the other woman. "Meet Johann Bach."

"Really?" Casey looked to Marla.

"No, he's not that Bach," Marla said.

Johann gave a slight bow. He knew his smile was a bit twisted, but he was getting so tired of that reaction from the up-timers. The two women nodded back. "So how many pipes in a pipe organ?" the question was repeated by Fraulein Matowski.

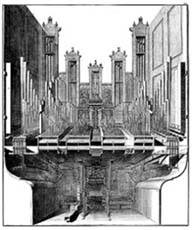

"That depends on the organ," Johann smiled. "I do not yet know how many will be in my organ, but . . ." He thought for a moment about the space he had to work in. ". . . if I realize my dreams it would not surprise me to see three thousand pipes, perhaps as much as two hundred more."

"Wow." Fraulein Matowski blinked. Johann noticed that her eyes were large, golden hazel, and gleaming in a heart-shaped face framed by shoulder-length walnut-hued hair stirred by a breeze. "Sounds like a good job for a Bach."

"Thank you, Fraulein Matowski." Johann bowed to her. With what he knew now, she had delivered him quite a compliment whether she meant to or not.

"Call me Staci."

"Thank you, Fraulein Staci." He bowed again.

"But enough of me," he continued. "What is happening with you? What is new in the musical life of Magdeburg since I left?"

"We're going to perform Händel's oratorio Messiah either in late December or early January." Marla pointed at him. "You should either be in the choir or in the orchestra. I know you said you play."

"Orchestra," Johann said. "Viola."

"Good. Come by the house tonight and talk to Franz. Meanwhile, we've got to get back to school and you've got a whitesmith to talk to. We'll see you later."

"'Bye, Herr Bach," Staci said as they walked away. "It was nice to meet you."

Johann watched them move off, Marla setting the pace. Just before they turned the corner, Staci looked back over her shoulder and smiled.

Johann stood for a moment, thinking of a pair of dancing hazel eyes. Then he shook his head and took off down the street. Once he got to the Gustavstrasse, the wide boulevard that bisected Magdeburg Altestadt, the old part of the actual city of Magdeburg, he turned north.

In a few minutes he was crossing the moat again, this time into Magdeburg Neustadt. He smiled at the thought of calling that part of the city "new." It was also surrounded by the city walls, and was older than his grandfather.

He hadn't learned every street in Magdeburg yet, but he knew enough to find the building he was looking for. He knocked on the door.

"Yes?" A young man answered the door.

"Herr Johann Bach, to see Master Philip Luder."

"Come in, Herr Bach." The youth gave a slight bow as he opened the door wide. Johann stepped through into a wave of heat. "The master is at the forge at the moment, but will be with you very quickly."

He conducted Johann to a chair set to one side, then stepped over to the forge set against the back wall of the building and spoke to a man of middle years who was stirring something in a crucible set above the coals. The man looked over his shoulder, handed the ladle to the younger man, and bustled toward Johann.

"Herr Bach! I am Philip Luder." The master wiped his hands on his leather apron and extended one to Johann. Johann stood to clasp hands with the man. Master Philip had a strong grasp, but didn't attempt to crush Johann's fingers. As a musician, he appreciated that.

"And what can I do for you, Herr Bach?" The whitesmith's eyebrows climbed his forehead for all the world like two bushy caterpillars. Johann had to bite his tongue for a moment to keep from grinning at him.

"Pipes, Master Luder. I need pipes—many pipes."

The master's eyebrows contracted downward. "Pipes." A vertical line appeared between the brows. "For water? For oil? For . . ." He looked expectantly at Johann.

"For music, Master Luder. I need pipes for a pipe organ."

"Ah!" A concerned expression appeared on the whitesmith's face. "Are you the one who will build the new pipe organ in that fancy new building that is beginning, or are you the one who will be rebuilding the organ in the Dom?"

Johann was taken back. "Rebuilding?"

"Oh, yes." The whitesmith nodded. "You are not from here, so you may not know that that black-souled Pappenheim, may he rot in Satan's hands, favorite tool that he is . . ." Luder spat into the forge. "Where was I?"

"The organ in the Dom?"

"Right. Pappenheim stripped all the metal work from the organ and sold it off to a jobber before he fled like a jackal with his tail between his legs."

Johann was horrified. "I hadn't heard. Was not that a Compenius instrument?"

Luder nodded again. "Aye, built by old Heinrich himself—the son, not the father—thirty years ago, they tell me. And a sweet instrument it was, although I'm no musician to say so. But no more, no more, thanks to Pappenheim eviscerating it . . ." The master's voice trailed off into muttered curses.

"I have met Master Heinrich the younger," Johann said. "He came to visit his son Ludwig, who lives in Erfurt. I learned much from the two of them."

"Ach, well, according to the word in the halls of the Dom, Herr Christoff Schultze, him who used to be Möllnvoigt for the archbishopric and is now the hand of Ludwig Fürst von Anhalt-Coethen, Gustav Adolf's administrator, has been in contact with the Compenius family, trying to get either Ludwig or his older brother Johann Heinrich to come and lead the repairs."

"If all the pipes were stolen, it will be more like building a new organ."

"You would know better than I would," Master Luder smiled. "But your name is Bach, not Compenius, so now that I think about it, you must have something to do with the new organ rather than the old."

"Indeed." Johann smiled back.

"Should I congratulate you or commiserate with you?"

"I will let you know in a few months, but probably the latter." The two men laughed together. Johann decided he liked Master Luder.

"So you come to me to talk about pipes."

"To talk about making the pipes, yes."

"Hmm. And how many pipes are we talking about?" One of those expressive eyebrows climbed a level, but the grin was still in place.

"Three thousand, maybe a bit more."

The eyebrow dropped and the grin faded. "Three . . ."

"Thousand. Maybe a bit more."

Master Luder stripped off his apron and threw it on a peg on the wall. He rolled down his shirtsleeves, took down a jacket from another peg, and crammed a hat on top of his bristling hair. "Come. This needs ale."

Johann followed the craftsman out of his shop and down the street. Luder said nothing until after they entered a tavern—it was The Green Horse, Johann noted—and ordered their ale.

"Three thousand pipes." Master Luder began as they sat down at a table.

"More or less," Johann replied.

"All different sizes, I suppose."

"Many sizes, yes, but not individually unique, no. Many pipes can be made and tuned from one size."

"Good. That will speed the work. Do you know yet how many sizes you will have?"

"Not yet. I may use wooden pipes for the largest ones, and I won't know how many metal sizes there will be until I make that decision."

"Pipe metal? Tin and lead alloy?"

"No. No lead in it. It dulls the sound. I want a bright sound to the pipes, so I want only tin, the purest tin you can get. English tin if you can get it."

"I can get it." Master Luder pursed his lips as his eyebrows crouched close together. "But enough for three thousand pipes will cost you. And I can't get it all at once."

Johann shrugged. "It costs what it costs. And as long as the pipes are done when I need them, it doesn't matter when the tin is available. But do you know how to make pipes?"

The craftsman took a healthy swallow of ale, then wiped his mustache and beard. "I do. I was a journeyman in Leipzig when my old master provided repairs to the university church organ. We had to replace a number of the pipes. I still remember what we did."

"Good. Then how much to put to use what you remember?"

Johann took a swig of his own ale as the bargaining began.

* * *

Marla looked up from the piano keyboard at a noise in the door. School was done for the day and she was relaxing a bit by playing.

"Hi, Staci. What's up?"

"Nothing. I just stopped by to see what you were up to."

Marla smiled as she always did when she heard Staci's voice. The powerful contralto was so surprising coming from her tiny frame. She waved her friend into the room. "Come on in."

Staci Matowski hesitated. "I don't want to interrupt anything."

"You're not interrupting. I was just improvising a little."

"Improvising?" Staci stepped over to the piano.

"Yeah. You take a musical theme, then try to make music out of it with variations and stuff."

"Sounds hard."

"It can be. Hey, what was your phone number?"

"Huh?"

"What was your phone number in Grantville?"

"534-3468. Why?"

Marla picked notes out on the piano keyboard. "G-E-F-E-F-A-C. There. That's the notes for your phone number." She set both hands on the keys and played with the resulting melody, adding chords and rhythms to it. After a minute or so, she brought it to a close.

"That was cool," Staci smiled.

"I'm not very good at it, so I work on it as often as I can."

Staci stepped back from the piano. "I didn't mean to interrupt you," she repeated.

"No problem. What do you want?"

Staci turned away and walked over to the window. She stared out for a moment, then she turned to face Marla. "This Johann Bach . . . what do you know about him?"

Marla leaned over and rested her arms on the music rack of the piano. "Not a lot. A good musician by anyone's standards. Seems to be a nice guy. Probably related to the Bach, but he hasn't heard from the researchers in Grantville to prove it yet."

Staci turned back to the window. After a moment, she asked, "Is he married?"

Marla's eyebrows rose in surprise. "No, not that I know of. Down-time men don't wear wedding rings, though, so it's hard to tell for sure."

"Franz does . . . wear a ring, I mean."

Marla blushed a little. "Yeah, well, Franz isn't your typical down-timer, either."

"Yeah." There was a long silence. Marla wasn't sure what Staci was getting at, but she was willing to wait for her to get to it in her own time.

"Marla . . ."

"Yeah?"

"Do you believe in love at first sight?"

Oh, my. "Um, maybe," she responded with caution. She didn't want to sound too out-in-left-field, here.

"I mean, when did you first know you loved Franz?"

Marla wasn't able to suppress the smile she always got when she thought of their first meeting. "Okay, you got me. He had me the night we met and he showed me how his hand had been crippled."

Staci turned with surprise on her face. "Pity? That's how it started for you?"

"No," Marla said with heat that surprised her. She calmed down. "No, it wasn't pity or sympathy. Empathy, now, that was probably a large part of it."

Staci tilted her head to one side. "What do you mean?"

"Understand that Franz lives for music. He is music, you might say. And that had been ripped away from him. You could see it in his face, in his eyes. There was a raw hole in his soul that he was bleeding from. I could see the pain in him, could feel it. And I knew that pain, because I thought I had lost the music when the Ring fell." She swallowed, reliving that moment. "It wasn't a moment of decision, of thought. I just . . ."

"You just stayed with him."

"Yeah." Marla nodded. "I stayed with him after that. Mind you, I don't think he was that fast to recognize it."

"But he did, eventually."

"Oh, yeah." Marla smiled a bit at the thought of that night as well.

There was another long moment of silence. Marla broke it with, "So, are you feeling . . . something . . . for Johann?"

Staci looked back out the window. "Something, I guess.

* * *

"So the wind trunks come up from the wind chest," Antonio Parigi mused, tracing his finger over the rough drawing Johann had just done, "and feed into the small wind chests under the manuals."

"Right," Johann nodded.

"Where does the wind go from there?"

"The player has to open one or more stops to open up passages from the small wind chest to the pipes. Pulling the knob pulls the slider out and aligns holes in the slider with holes in the top of the chest and the bottom of the wind trunks to the pipes."

"Hmm." The architect pulled on his little spike of a beard. "So the routing of the wind in an organ is not unlike an exercise in fluidics."

"So I've been told." Johann smiled. "At least if this system springs a leak, nothing floods."

Parigi chuckled. "True." He tapped a finger on the papers. "So how have you progressed in moving from the concept to the reality?"

"The carpenters are ready to begin the main wind chest, but that will have to wait until we are closer to the completion of the chamber that will hold it. I still have not found a reliable man to make bellows." Johann frowned at the thought. This was on the verge of becoming a problem, which he did not need this early in the life of the organ design and build.

"They mentioned using an electric fan," Parigi reminded him.

Johann sighed. "I know. But I do not know anything about that. I am not certain how to incorporate that into what I do know."

"A not uncommon problem for those of us born in this time," Parigi chuckled. "The building project has an electrician assigned to it. Talk to her."

"Her?"

"Her."

Johann grimaced and shook his head.

* * *

"Excuse me, please? Are you the electrician?" Johann had been pointed toward a table where coils of wire and odd metal fixtures were piled in haphazard towers that leaned in various directions.

"You're talkin' to her." The head that was bowed over a contraption on the table didn't move.

"I am Johann Bach."

The head rose, and eyes blinked at him from behind small rectangular glasses. "Oh. You're the organ guy, right?"

"Yes."

"Just a sec." The head bowed back down for a moment; a screwdriver was twisted. "Ah, that's got it." The contraption was pushed aside as she looked up at Johann. "What can I do for you?"

The woman looked familiar to Johann, but he knew he'd never seen her before. He pushed that thought aside. "I need to move air to fill the wind chest for the organ. In other times I would use bellows, several of them. But now they tell me I should use an electric fan. And . . ."

"And you need to know what one is, right?"

"Yes." Johann suppressed the irritation that flared from being interrupted.

She picked up a flat piece of metal and waved it at Johann. He felt air stirring against his face. "That's a fan, right? It moves air?"

Johann's irritation flared again, and he had to step on it harder. "I understand that, yes."

"Sorry, didn't mean to be patronizing." The electrician set the metal piece back on the table. "Okay, now an electric motor can turn very fast." She picked up a tool from the table and squeezed a trigger, which produced a whining sound as the pointed end began to spin rapidly. "Like so."

"And if one can figure out a way to attach a fan to that motor," Johann pointed to her now-quiet tool, "one can move a lot of air rapidly."

He was rewarded with a bright smile. "Right."

"So what would it take to build one, and how much air would it move?"

"How much air gets moved would depend on the size and speed of the fan. We'd need to talk to an engineer about that. But I can't see that building one would be all that difficult. A medium sized electric motor with a fan blade assembly on it wouldn't be hard."

"An engineer. You mean like Herr Otto Gericke?"

"No, I was thinking more along the line of Jere Haygood."

"Ah, Frau Haygood's husband?" Johann was aware of the oddness of the up-timers, where the wife would take the husband's surname when they married.

"Right."

"But who would build this for me?"

The electrician steepled her fingers. "I can get the motor, once we know what we need to build. Who builds it depends on what you make the fan part out of—wood, sheet metal, even tin."

Johann nodded. That made sense. And wood would probably be the cheapest material and the quickest to work. He nodded again.

"So, I need to consult with Herr Haygood."

"Yep. I can't help you with the calculations for designing it."

"Good. I will seek him out." Johann gave a short bow. "Thank you very much for your assistance, Fraulein . . ." He realized he didn't know her name.

"Matowski. Melanie Matowski." She stood and offered her hand.

Johann grasped it, to have his own firmly shaken. "Are you related to Fraulein Anastasia Matowski?"

Another bright grin. "My sister Staci. She's the teacher, I'm the hands-on person."

Fraulein Melanie was perhaps an inch or two taller than her sister, and her face was somewhat rounder than Fraulein Anastasia's heart-shaped visage, but now that his attention had been drawn to it, he could see the resemblance.

"My thanks again."

"No problem."

Johann glanced back for a moment, to see that Fraulein Matowski had resumed her seat at the table and was again head-down over her work. An . . . interesting young woman, he mused to himself as he walked out of the workspace.

* * *

"Hey, Bach!"

Johann looked up from where he had stooped to enter the Green Horse. He saw a hand being waved and waved back. After collecting a mug of ale, he made his way toward the table.

"Hey, Johann," Marla said. "Pull up a chair and sit on the floor."

Johann stopped halfway down to the bench, frozen as he untangled that thought in his mind. He decided after a moment that it was more of the ubiquitous but slightly off-pitch up-time humor, and continued his descent to his seat. The others nodded or waved a hand at him, and he nodded back.

It was Marla's usual crew, the musicians who accompanied her in her singing, plus a couple of extras. Johann's eyes lit upon two familiar faces. At the other end of the table sat the two young women that had accompanied Frau Marla several days ago. He considered them over the rim of his mug. Fraulein Stevenson was laughing, leaning across Franz Sylwester to say something to Frau Marla. Fraulein Matowski—Anastasia Matowski, he reminded himself—sat across the table from them with a slight smile on her face, fingers laced around a coffee cup.

Something was different. It took Johann a few moments to realize that Fraulein Anastasia's hair was short. Very short. Extremely short. It looked as if someone had cut all her hair to less than finger length.

Now it was understood that up-time women, among their many freedoms and licenses, were much more casual about the treatment of their hair than the women Johann had known all his life. And outside of Frau Marla, he hadn't seen many of them who wore their hair long. But shorter than Marla's hair left pretty of room for length—which Fraulein Anastasia's hair no longer possessed.

Johann considered the young woman. Perhaps she had been ill, and they had cut off her hair for some reason to help her heal. Doctors had been known to do stranger things, he knew.

The other thought that attempted to cross his mind he pushed away. Surely if she had committed some sin that a pastor or congregation had levied this as a punishment she would not be here surrounded by her friends. Perish the thought.

He let the conversations flow around him, content to sip his ale and look from under lowered lids at the young woman. Whatever the reason for the cutting of her hair, Johann had to admit it gave a certain charm to her.

Marla raised her head and looked toward the bar. "Woops! Okay, folks, time to do our thing. Let's go." Instruments were pulled from cases and bags, and Marla and Friends trooped to the open spot at the end of the tavern.

Johann found the evening enjoyable. He still wasn't very familiar with the songs that Marla and the men that clustered around her liked to perform. They were for the most part bright and bouncy songs, many of which would have had people dancing to them had they been done at a town fair or village market. He remembered being told they were mostly from up-time Ireland, which he had some trouble crediting. Irishmen in the here and now weren't exactly common in Wechmar and Erfurt where he grew up, but the few that he'd met here in Magdeburg did not seem to fit with bright and bouncy. A more moody, surly, snarling group of men he'd never met before, and never wished to again.

Regardless of their origin, by now the songs were familiar to the crowd in the Green Horse, enough so that they were singing along with some of the choruses. Johann hummed instead, foot tapping and fingers wagging in the air.

The music reached a resting place after the musician's finished Nell Flaherty's Drake with a flourish. Marla was panting from the rapid pace of the song with its intricate lyrics. "Staci!" she called out.

Johann watched as Fraulein Matowski looked around. Marla beckoned her. She shook her head, and Marla beckoned more energetically. Fraulein Stevenson reached across the table and nudged her. "Go on. You know she won't take no for an answer."

Fraulein Matowski shrugged, drained her coffee cup and stood. As she walked toward the musicians, Johann picked up his mug and slid down the bench to sit closer to Fraulein Stevenson. She looked over at him and smiled, then returned her gaze to her friends.

Marla waved for quiet. "We're going to do an old song from up-time America," she said. "Leastways, it was old for us, before the Ring fell—close to two hundred years, anyway. Listen to Oh Shenandoah."

The musicians rearranged themselves, with Franz and Marla stepping forward and placing Fraulein Matowski in the middle. Franz lifted his bow and began playing a haunting melody. It soared and fell, flowed and ebbed, and at length paused for a moment of silence, delicately balanced, as if it stood on the head of a pin.

Oh Shenandoah,

I long to hear you,

Away you rolling river,

A woman's voice began, and Franz played a descant. Johann was caught by surprise nonetheless, for it was not the voice he expected. It was Fraulein Matowski that he heard, singing in a strong alto.

Oh Shenandoah,

I long to hear you,

Away, I'm bound away

'Cross the wide Missouri

Marla's friend was not a vocalist to be a peer with Marla, Johann pursed his lips. Still, he nodded. Very few singers would equal Marla, and one could be less than Marla and still be very good. Fraulein Matowski was good—maybe even very good. He relaxed and listened to the song.

Oh Shenandoah,

I love your daughter,

Away you rolling river,

When the second verse began, the other instruments joined Franz in providing a musical platform to lift Fraulein Matowski's voice to a new level. Marla came in as well, singing now the descant that Franz had played in the first verse.

I'll take her 'cross

Your rolling water,

Away, I'm bound away

'Cross the wide Missouri.

Johann closed his eyes to avert distractions and listened with concentration. This was not a bravura performance; this was not something that he would take to the courts of the Emperor or the Hoch-Adel. Still and all, it was beautiful, presented with no affectation by the musicians, and he drank it in.

The remaining verses followed the pattern of the second.

'Tis seven years,

I've been a rover,

Away you rolling river,

When I return,

I'll be your lover,

Away, I'm bound away

'Cross the wide Missouri.

Oh Shenandoah,

I'm bound to leave you.

Away you rolling river,

Oh Shenandoah,

I'll not deceive you.

Away, I'm bound away

'Cross the wide Missouri.

Away, I'm bound away

'Cross the wide Missouri.

After the last verse, Rudolf Tuchman's flute carried the melody again as a solo line, rising and falling, falling and rising, to fade away on the final note. Johann—indeed, the whole audience—sat in silence for a long moment, until applause broke out from the back of the room.

Johann leaned toward Fraulein Stevenson under the cover of the applause. "That was well done."

She nodded vigorously. "Marla and Staci did that as a duet for choir contest their senior year in high school." She counted her fingers. "That was three years ago, I think. Hard to tell exactly with the Ring of Fire in the middle of it." She flipped her hand in the air. "Anyway, they got the highest rank possible from the judges." Her shoulders heaved in a sigh. "I wish I could sing half that good."

"Are you not a musician, then, Fraulein Stevenson?"

"Call me Casey. Fraulein makes me feel like an old maid aunt. And no, I'm not a musician. I mean, my mother taught me some piano, but the real talent skipped me and went to my brother, I think. I'm just a school teacher." She paused for a moment. "Although I think I'm pretty good at that."

"And is Fraulein Matowski a musician or a school teacher?" Johann was intrigued.

"Neither one." Casey gave a wicked grin. "She's a dancer, she is, and everything else is just what she has to do to be able to dance."

"Dancer?" Johann wasn't sure what to make of that.

"Sure. Didn't you see the performance of A Falcon Falls back in July? I think you were in town then, maybe."

Johann thought back, then shook his head. "No, I heard about it, but I did not see it. Some kind of big staged thing with many set dances, is what I gathered. Was it an opera?"

"No, it was a ballet of sorts, a production consisting solely of dances. Staci danced one of the lead roles in it. Staci's mother Bitty produced it. She's taught dance in Grantville since forever. Everybody who's studied dance started with her, including me."

Johann's eyes drifted back to Fraulein Matowski—Staci. She was smiling and singing along, clapping her hands as the musicians played another fast song. "She looks so young."

Casey followed his glance. "Yeah, I know what you mean. She looks like she's a pixie, about twelve or thirteen years old, especially since she got her hair cut. She's younger than I am, but she's actually older than Marla, by at least a couple of months." She counted her fingers again. "Yep. She's twenty-three now."

Johann watched as the song dissolved into laughter. His gaze narrowed until his vision was filled only with the shining face of the smallest performer. His mouth curved in a small smile.

* * *

The evening came to a close, and Marla's friends packed up their instruments, laughing and talking loudly to each other. Johann watched with a smile. They reminded him so much of his younger brothers; full of enthusiasm and energy, one moment boasting of how well they performed, and in the next pointing to a friend and claiming that he was the root of all musical evil because he bobbled a note. Of course, the friend responded in like kind, and laughter arose from around them.

Johann's eyes never strayed far from Fraulein Staci. She pulled on a faded blue jacket while she chattered to Marla and Casey, then picked up a cap of the style the up-timers called baseball and placed it on her head. It was black, with a large orange P symbol on the front of it. It occurred to him that she looked even more like a boy than before. She caught him looking at her, and grinned at him.

He pointed to the cap. She looked puzzled and pulled it off.

"What does the letter stand for?" he asked, stepping closer.

"Pittsburgh." Staci put the cap back on and tugged it into place.

"Pittsburgh." He rolled the word around in his mind, and made the obvious translation. "Fort Pitt?"

"Yep. That's what the first structure was for a city in the up-time state of Pennsylvania. Became a very large city, about a hundred miles north of where Grantville was before the Ring fell. This," Staci touched a finger to the bill of the cap, "is from the city's baseball team, called the Pirates." She started closing snaps on the front of the jacket. Casey stepped up beside her and they started toward the door.

Johann fell in on the other side of her. "Did someone in your family play for this baseball team?" He'd been to Grantville. He congratulated himself on knowing what baseball was.

Both the young women broke out in laughter. "No, no," Staci gasped after a few moments. Johann held the door open and followed them out into the night air. "Not that my dad didn't try to get my brothers interested in the idea. No, Dad is a big fan of the Pirates." She tilted her head and looked over at Johann. "Actually, I guess was a big fan is the way to say it. About the biggest in Grantville, and that's saying something. And he and all his baseball buddies went into mourning when the shock of the Ring of Fire wore off and they realized they'd never see another Pirates game. No more games on TV, no more weekend trips up to Pittsburgh to see them play. It was downright gloomy around the house for a long time. They picked up on the local games when those started, but it wasn't the same. That was one of the reasons why I took the teacher's job here in Magdeburg."

"One of them," Casey snickered.

Staci shoved her friend's shoulder, causing her to stagger a step or two. "You should talk. You were the one egging me on. You just wanted a roommate so you could be closer to Carl Schockley."

"So you teach?" Johann prompted.

"Yeah, that's my day job."

"Day job?"

"It's what I do to feed myself and pay my expenses. It's not who I am, though. I don't want to be known at the end of my life as a teacher. Not that there's anything wrong with that," she hurried to say. "It's just that I'd rather have something on my tombstone besides 'She taught grammar to five thousand four hundred and ninety-seven snot-nosed little girls.'"

Casey laughed again.

"I'm serious," Staci maintained. She looked around as they wandered down the street. Johann knew more or less where they were, but wasn't sure where they were going. He was content to let them guide his steps.

Staci shivered. "I still have trouble getting used to how crowded the houses are here in Magdeburg."

Crowded? Johann looked around. Everything looked normal to him.

"I mean," she continued, "they're all built right next to each other, walls touching. There's no yards, there's no space. You've been to Grantville," Staci appealed to Johann, "you know what I mean. Even in the downtown district there's room. Here, except for the new boulevards, most of the streets are so narrow I can stand in the middle and almost touch the buildings on both sides."

Johann tried to see through the eyes of an up-timer, and began to understand what she was talking about. He remembered all the open spaces in the town, all the wide avenues and large lawns and gardens. He also remembered thinking that the up-time must have been very rich for everyone to live on private estates. Now he looked around with that vision, and understood why Staci shivered. The only wide open spaces in Magdeburg were the space around the Dom, and Hans Richter Square and the Gustavstrasse that led into it. Well, and the places where buildings that had burned in Tilly's sack of the city had not been rebuilt yet, but he supposed those didn't count.

"It is the way it is done here and now," he said with a shrug. "Perhaps in time it will change, but not soon."

Staci shoved her hands in her jacket pockets and kicked a stone down the street. "Oh, I can deal with it. It just makes me feel claustrophobic sometimes, is all." She raised her head up and the moonlight lit her smile. "Of course, having everything built close together like this does mean that no place in town is very far away from anyplace else. It's easy to walk."

And so the three of them continued walking. "Where are we going?" Johann finally asked.

"Home," the young women both said at the same time, which occasioned another spurt of laughter. "Not too far," Casey added.

Staci nodded. She looked up at Johann again. "So, Johann, have you figured out yet how you're related to Johann Sebastian?"

He shook his head. "No, the report from Grantville hasn't arrived yet. But soon, soon I will know."

"What's so important about him, anyway?"

Johann stopped still, astounded. The two young women went a step or two further, then turned and faced him.

Casey laughed, he presumed at the expression on his face. "You'll have to forgive her, Johann. She's a dancer. To her, real music begins with the Romantic era composers, a hundred years after Master Bach."

Staci slugged her friend in the shoulder again. "I'm not that bad! And you're a dancer, too."

"Are too!" Casey slugged her back. She looked over at Johann. "I already told you I'm not much of a musician, but I know this much. Do you want to tell her, or do you want me to?"

Johann shook his head. "How can I say this to make you see?" It amazed him that someone with Staci's talent for music didn't immediately grasp this understanding. A thought occurred to him. "Let me state it like thus: if music were a religion, Johann Sebastian Bach would be its Moses—no, Saints Peter and Paul combined."

In an age where what religion a man professed might determine whether he was breathing by the end of the day, that was a strong statement. He could see that Staci was impressed.

"Okay," she said. "I'll have to take your word for it. Casey's right. If I can't dance to it or sing it, I don't pay much attention to music. But that . . . if that's how important that old man is to you, then go for it. Build your organ and play his music."

"I intend to," Johann said, pleased at her encouragement. "It may well become my life's work."

They wandered on in silence for a space, until the ladies stopped in front of an ornate door. Johann looked at the imposing building, then back at them. He tilted his head to one side, and they laughed.

"I'd call it our rooming house," Staci offered, "but it's actually the school, and we have an apartment in it. Thanks for seeing us home."

Johann gave a slight bow. "It was my pleasure, frauleins. Good night to you, and until another time." He dipped his head again, then watched as they stepped up to the doorway and entered the house.

* * *

Casey closed the door to their room and whirled on Staci. "You, girlfriend, have got an admirer."

"Do I?" Staci took her cap off and tossed it on the wash stand. She started unsnapping her denim jacket.

Casey threw her hands in the air. "Staci, the man spent the entire evening watching you. Almost everything he said while you were performing were questions about you. I could barely get him to look at me."

"What of it?"

"What of it?" Casey snapped. "What of it? He's literate, he's educated, he knows the arts well enough that he has a chance of understanding you, and he doesn't come across as a down-time Lothario looking to conquer an up-time maiden. You might consider giving him a bit of encouragement."

"Mmm." Staci hung her jacket on a peg in the wall, then turned back to her roommate. "First of all, you're not supposed to be flirting with other men. You're pretty locked in to Carl, as I recall. And second of all . . . look, I admit the man is presentable, if not exactly handsome, and I'm flattered that he's asking about me. But he's years older than I am, and he's a down-timer."

"So?"

"So, I'm not sure he's flexible enough to accept me for what I am. I'm a dancer, I'm always going to be a dancer, and any man who comes into my life has to accept that. No, he has to do more than accept that—he has to support that."

Staci crossed her arms and looked at her roommate. "I'll give Bach points for not being a down-time version of a jock. He's polite and well-mannered. And he appears to be everything you say he is. I'll even give him points for being passionate about his art. If anyone can understand that, I can. The question is, will he allow me to be equally passionate about my art?"

Casey saw the expression on Staci's face shift through fleeting impressions of loneliness and fear before settling into one of resolution.

"Can he understand me?" Staci asked.

Although it was not a rhetorical question, Casey had no answer.

* * *

For a long moment Johann observed the closed door, then gave a sharp nod and turned away.

Staci, he mused to himself. She was a woman of passion, he decided. A woman who knew what she wanted and was not afraid to say so and to work to that end. He liked that she understood his passion in turn.

Thoughts crossed Johann's mind of Barbara Hoffmann, daughter of Johann Hoffman, Stadtpfeifer in Erfurt, his former employer. He knew there was an assumption on the part of the father and daughter that he would marry Barbara. It was such a common thing, that an ambitious musician would find an assistant's place with such a man as the Stadtpfeifer, marry one of his daughters, and eventually assume the place of the father when he died or retired.

Johann tried to bring Barbara's visage to mind: round face, almost doughy in complexion, framed by limp brown hair, with weak short-sighted eyes peering out at the world in constant confusion and startlement. Another's face kept forming in his mind: heart-shaped, with golden hazel eyes shining dancing gleaming above smiling lips.

His steps slowed, then stopped. Could he even think of returning to Erfurt now? Could he even think of returning to Barbara—poor, placid, insipid Barbara?

He became aware of someone standing nearby, and looked over to see a city watchman scrutinizing him. "Are you drunk, fellow?"

"No, merely reaching a decision."

The watchman looked at him some more, then nodded. "Be on your way, then. Night streets are not for good citizens."

Johann took his advice and headed for his lodgings.

Grantville, Johann mused as he wandered, such changes you have wrought. You have rocked the crucible of Europe, winnowed the ranks of the mighty, disconcerted the minds of the philosophers and scholars and pastors. Yet even in the midst of that you have deigned to reach down and touch the life of one poor musician.

His steps slowed, then stopped again. "God," Johann whispered. "You are indeed an Escher. What would have been my life is now revealed to be merely a figment, a parody, of what will now come to pass. I do not know your will for me for the future, but I pray that it includes both the music of Sebastian and the presence of Anastasia Matowski."

* * *