The liquid in the shallow dish ignited, releasing a burst of yellow-green fire. The audience, a curious mix of Tuscan scholars and glitterati, applauded.

Lewis Philip Bartolli acknowledged the applause with a briefly lifted hand. "This lovely green reveals the presence of the element boron, which was not known to the ancients. The liquid is distilled spirits, which burn nicely. To the spirits, I added what chemists call boric acid. This boric acid contains one atom of boron, three of oxygen, and three of hydrogen, and it was obtained from the volcanic emissions of the Maremma of southern Tuscany."

A servant in the livery of the reigning Grand Duke of Tuscany, Ferdinand de Medici, silently glided down the aisle, and whispered into the ear of Andrea di Giovanni Battista Cioli, the Tuscan Secretary of State. Cioli flinched, then muttered something to his companion, the teenaged Prince Leopold.

"The green color of the flame is the result of the excitation of the electrons of boron. Next, I would like to show you—"

Cioli rose abruptly. "On behalf of the Serenissime Grand Duke, of His Highness don Leopoldo, the learned fellows of the Academy, our guests, and myself, I would like to thank Dottore Bartolli for a fascinating presentation on chemistry. Unfortunately, we must excuse him, as he has a pressing engagement."

I do? But Lewis kept this thought to himself, and bowed.

The crowd filed out. The increased hubbub woke up Galileo Galilei, who was snoring away in a front seat. Like Lewis, the great man was expected to entertain the court. Lewis gave chemistry demonstrations during the day, and Galileo set up his telescope and explained the wonders of the night sky. Since he was up half the night, and was more than twice Lewis' age, it was perhaps understandable that he couldn't always stay awake for Lewis' lecture.

"Um, what. Oh. Wonderful presentation, Lewis. Another nail in the coffin of the Aristotelians."

Cioli put his arm around Lewis. "Walk with me, dear chemist. You can take my coach to your pressing engagement." He turned to Leopold. "Your Highness, you are welcome to join us, I think you will find the matter of interest." Leopold was the grand duke's youngest brother.

In the privacy of the coach, Lewis finally could speak his mind. "For Christ's sake, what is this all about?"

"Grand Duke Ferdinando was dining with one of his leading noblemen. The man suddenly showed signs of severe gastric distress."

"I am not a physician—"

"You don't need to be; he is already dead."

"And you suspect—"

"Murder. Yes. By poison, we think. So we need your expertise."

Prince Leopold chimed in. "Surely your mentor, the great Sherlock Holmes, would expect you to assist us."

The grand duke and his brothers had not initially grasped the concept that the Sherlock Holmes Lewis had told them about was a fictional character, and Lewis' business associate in Tuscany, Niccolo Cavriani, had warned Lewis not to correct them. "In general, it is not a good idea to tell a ruler that he is wrong. Especially when the error is a harmless one" were his words. Hence, earlier that year, Lewis had not protested when Grand Duke Ferdinand proclaimed the young up-timer to be "Consulting Detective to the Grand Duchy of Tuscany."

They rode in silence for a few minutes.

Cioli cleared his throat. "During your investigation, Lewis, please keep in mind that the deceased lord might not have been the real target of the poisoner. The grand duke is not popular in all circles of power in Tuscany. Or beyond. Especially since he has shown favor to you, and thus, however obliquely, to your United States of Europe."

"So you think it was an assassination attempt gone amiss?"

Cioli shrugged. "Who can say? But you see that the investigation is of the greatest importance. You doubtless will be rewarded appropriately for proving the identity the poisoner." Cioli was too polite to mention the consequences of failure.

Or perhaps he thought it more effective to leave them to Lewis' imagination.

* * *

The coach stopped in front of a villa. The footman stepped down and open the door. Lewis was about to step out when he was stopped by a soldier. He aimed a lantern into the compartment. "Excuse me, Your Highness, Your Lordship, Dottore. I have my orders. Would you wait just a moment, please?" He closed the door.

"This is exciting, isn't it, Dottore?" asked Leopold.

Lewis reminded himself that Leopold was only sixteen. With the gravitas that came from being fully two years older, Lewis acknowledged that the case might have its interesting aspects.

When the door was opened once more, it was to reveal the familiar visage of the ruler of Tuscany. "A curious turn of events, eh, Lewis?".

"Yes, Your Grace."

"But with you here, the game is now afoot."

Lewis fought back a groan. "Indeed."

"Thank you for your assistance, Lord Cioli. Oh, and hi, Leopoldo. Try not to bother Lewis with too many questions."

Ferdinand beckoned to a tall fellow in an officer's uniform. "This is Lieutenant Cosimo Capponi. He and his men will help you conduct searches, question suspects, and so forth. I want to make sure that you encounter no difficulties on account of your being a foreigner."

Cosimo bowed. "I look forward to working with you, Dottore. I will make sure that you can go where you need to go, and that people answer your questions. And of course I can question witnesses on your behalf."

Cosimo pointed out two soldiers. "Carlo and Rocco. If you need a suspect watched, or a door broken in, they're your men.

"Also permit me to introduce Giovanni di Niccolo Ronconi, who is one of our family physicians. A Padua man."

"I'm a West Virginia man, myself," said Lewis. The Tuscans all nodded sagely.

"But please proceed with your investigations, Lewis."

"Your Grace, who was at the table besides yourself?"

"Pietro, the deceased. His wife Silvia, and their children Domenico and Olimpia. The Senator Francesco di Alessandro Arrighi, and his wife Lucrezia. The banker Alberto Spinelli, and his sister Isabella. La Cecchina—"

"I beg your pardon? La Cecchina? 'The Songbird,' who's that?"

"I perceive you are not a musician, Lewis," Ferdinand said. "Why not? Didn't Sherlock Holmes play the violin?"

Cioli intervened. "La Cecchina is the composer and singer Francesca Caccini. She sang for our court for at least two decades. Maria of Tuscany, the Queen of France, tried to steal her from us but her uncle, Ferdinando the First, forbade Francesca to leave."

"A wise move. She was, I think, the first woman to write an opera. Do you remember it, Cioli? It was 'La liberazione di Ruggiero dall'isola d'Alcina'; it was performed at my villa in 1625."

"It was exquisite. She married a Luccan nobleman, he died, and she returned to Ferdinando's service last year."

"That's right. And then there was Lorenzo Pippi, the poet. Or perhaps I should say Perlone Zipoli, since that's his pen name."

"Would-be poet," muttered Cioli. "Wise of him to use a pen name. Should have stuck to painting."

Ferdinand laughed. "Perhaps a half-dozen others whose names slip my mind. Silvia can tell you who they were."

"So describe the dinner," Lewis prompted. "What was served, who ate what, that sort of thing. And when did Pietro show the first signs of distress?"

"Hmm . . . first course was prosciutto cooked in wine and Neapolitan spice cakes. Those were served off the sideboard, 'help yourself.' I did."

"No spit-roasted songbirds, this time?" asked Leopold.

Cioli shook his head minutely. "Now that wouldn't have been very polite, with Francesca Caccini in attendance."

Ferdinand chuckled. "Second course, several different roasts. I had the goat and the rabbit, I am not sure what else there was.

"For the third course, there was a stuffed goose, smothered with almonds, with cheese, sugar and cinnamon on the side. Also Turkish-style rice, in milk, with more sugar and cinnamon sprinkled over it. Cabbage soup with sausages half-submerged, like those submarines you once told me about, Lewis. And boiled calves' feet. How could I forget that?

"We saw, but never got to taste, the fourth course, the desserts. They were arranged on the sideboard. Quince pastries. Pear tarts. Leopoldo, do you remember the time—"

"Please, brother, don't tell them."

"Oh, very well. More cheese. More almonds. Roast chestnuts. My, it's making me hungry just thinking about them. And it's barely an hour past sunset.

"Anyway, La Cecchina sang between the first and second courses."

"Paying for her supper," Leopold said.

Better than listening to restaurant muzak. Or worse, karaoke, thought Lewis.

"Lorenzo recited a few of his poems between the second and third courses. That's when Pietro started seeming out of sorts."

"And no wonder," grumbled Cioli.

"The remains of the third course had just been carried off and we were heading toward the sideboard, when Pietro clutched his stomach and claimed he was nauseous. We urged him to lie down, but he refused. Then he vomited.

"Silvia ordered the servants to carry him to the nearest couch and lie him down there. At that point of course, none of us were thinking about poison."

"Or dessert," Leopold said.

Ferdinand gave his brother a quelling look. "We assumed it was just a case of indigestion. At worst, that he ate something that was spoiled. Pietro complained that he was thirsty, and we brought him some wine. He seemed to have difficulty in swallowing, and he complained that his throat was sore. He soon vomited again.

"When Pietro was still in great distress an hour later, I sent a messenger to fetch Dottore Ronconi. Since the incident happened in my presence, I was insistent that Pietro be seen by the best doctor in Florence." Ronconi bowed.

"Ronconi will have to tell you what happened next."

Ronconi took a deep breath. "I came and questioned Pietro. He told me that he was of the opinion that there were people 'out to get him.'"

Lewis raised his eyebrows. "So he thought he was poisoned. Did he name any names?"

"He did not. He said that they must be in league with the Devil to get through his defenses."

"Defenses?"

"He has an armed guard at the door," Cioli said. "And I have heard that he has detailed servants to spy on each other, and that it is rare for a servant to stay more than a year or two before being dismissed on suspicion of wrongdoing. It is not a happy household."

"In any event, I examined him," said Ronconi. "Besides the obvious problem of the nausea and repeated vomiting, his stomach was very sensitive to pressure. He found even a light touch to be painful. I prescribed some medications, and departed.

"The following morning, I received a message from Silvia, urging my return. He had had an attack of diarrhea. Several in fact. By the time I arrived, he was in an advanced state of tenesmus."

"No medical gobbledygook, please," ordered Ferdinand.

"You feel you have to poop, and you can't. And it hurts." Ronconi shrugged. "It was at that point that I began to wonder whether there was some truth to Pietro's speculations, and I asked that the leftovers be gathered together for testing."

"I am surprised that the servants hadn't eaten them all by then," Leopold said. Since he was a sixteen year old boy, the concept of failing to eat any available food was no doubt alien to him.

"They had, indeed, eaten most of what had been left from the first and second courses, but naturally that tended to suggest that those courses were free of any taint. The servants had not disturbed the third course; no doubt Pietro's sufferings discouraged them from doing so.

"Hence, I was able to feed the remains of the third course to the family dog, and he seemed none the worse for the experience."

Clearly, thought Lewis, animal rights have yet too make much headway in early modern Italy.

"That quieted my concerns for a time. But the next day, Pietro's skin became cold and clammy, his pulse weakened, and at last he died."

"Were his wife and children present? How did they react to his death?" asked Ferdinand sharply.

"The wife and children seemed properly remorseful." He spread his hands. "There is not much left to say. He passed from my care to that of Our Lord and Savior."

Ferdinand gripped Lewis' shoulder, then released it. "In view of the allegations of poisoning, I thought it appropriate to call upon my 'Consulting Detective.' Don't disappoint me."

"Don't forget what I said about keeping your mind open as to whom the target might have been," Cioli added, softly.

"Well, there are a few options. I can do a Marsh test for arsenic on the remaining food."

"I am sorry, Ispettore Bartolli," the doctor said, "but none remain. The dog ate it all."

"Well, then—I don't suppose you saved any of the vomit?"

"No, I'm sorry. The servants cleaned it up. There might be a little staining his clothing, but I can't make any promises."

"Doesn't matter. I will just have to ask you, in the Grand Duke's name, to perform an autopsy. You can examine the stomach lining for signs of damage, and I can test the contents for arsenic and anything else I can think of.

"I will need to interview the family. One by one, if you please. I'll need one of your men, Cosimo, to act as a witness."

"I'll give you Rocco, he has some letters."

"Good. And Cosimo, if you would interview all the servants. Again, one by one, so they can't influence each other."

"Right, but I can assure you that the servants are probably hoarse from all the gabbing they've done already."

* * *

"I am sorry for your loss," Lewis offered.

The widow, Silvia, dabbed at the corner of her eye with a small handkerchief. Suddenly Lewis was reminded of a scene in a film noir movie. He couldn't remember the name. He was pretty sure that the widow in that movie turned out to be guilty, though.

"Thank you."

"I regret that I must ask you some questions."

"I understand . . . the Grand Duke told me. . . ."

"Perhaps he also told you that I am a stranger to this city, even to this time. You can trust me to seek the truth."

"At least as long as that truth isn't politically inconvenient for the grand duke."

"Even then, I might surprise you." Lewis hoped so, at least.

"Ask your questions."

Lewis asked her everything a mystery reader or crime TV fan might expect him to ask. The poisonous substances which were kept in the house or its grounds, and whether they had shown signs of recent use. The names and duties of the servants, their term of service, their past employers, and their whereabouts on the day that Pietro was stricken. The medications which Pietro had taken over the past month or so. The names and business of any visitors within the same period, and the dates of their visits. Who might be expected to benefit from or take pleasure in Pietro's death.

"Is it true that he thought someone wanted to kill him?"

"Yes."

"When did he first form this belief?"

"Several years ago. First he was attacked by ruffians at night, and was saved by the chance appearance of a couple of young noblemen. And then he was standing by a building, and was grazed by a falling brick."

"He saw someone drop the brick on him?"

"No, he said it happened too quickly."

"And do you think he was right, that he was in danger?"

Silvia shrugged. "This is Florence, who can say? Politics can be vicious. And commerce, even more vicious."

You aren't being paranoid if people really are out to get you, Lewis mused.

Domenico was a sullen twenty-something of no clear occupation. Other, perhaps, than his former occupation of "Waiting for Pop to Die So I Can Make a Real Dent in the Family Fortune." He disavowed any knowledge of poisons or medicines, not that in the seventeenth century there was a big difference between the two.

Olimpia was equally irritating, in her own special way. While Domenico tried to answer every questions with a single word—and then, only after a long pause, Olimpia was obviously in training for the Run-On Sentence Olympic event.

Before leaving, Lewis took samples of Domenico's tonic, and Silvia and Olimpia's cosmetics. He also borrowed the household accounts book.

* * *

Lewis and Cosimo compared notes.

"I spoke to Pietro's manservant, Taddeo. He told me something peculiar. Seems that Pietro was in the habit of making trips by himself, perhaps once every other month. Went in disguise."

"That's interesting. Sounds like a Clue with a capital C."

"Frustrating, is what I'd call it. If he were alive, I could have him tailed. With him dead, I can't follow up on it."

"If he weren't dead, we wouldn't be talking about it in the first place."

"It's too bad. I would have looked forward to tailing him. Probably lead me through three or four taverns a night. Perhaps even a brothel or two. And I would have to buy drinks, and so forth, all at Medici expense. So I didn't look suspicious, you see."

"I do indeed."

"I feel cheated, I must say."

"Pietro ever say anything about why he made the trips?"

"Apparently not. As you heard, Pietro was secretive. Didn't trust his own servants. Might have been going to see a girl, but I rather think it was something political. If it was directed against the Medicis, perhaps it's just as well he's dead."

Cosimo cocked his head. "Any great insights? Has Sherlock Holmes spoken to you from beyond the Great Unknown?"

"Well, a detective looks for who has means, motive and opportunity. The family members, and the servants, of course have opportunity. And often motive, too. As to means—by God Almighty, there's arsenic everywhere! In Domenico's tonic, in Silvia and Olimpia's face-powder, in the servant's storeroom. They use it to kill rats, they say.

"If my chemical tests show that Pietro was poisoned, it won't be a surprise to me. The surprise is that everyone else in the damn household is still alive!"

* * *

"Signorina Bartolli is waiting for you in the courtyard," the butler said.

Lewis nearly dropped the instruments he was carrying. "Who?"

"Your sister, Marina Bartolli." The servant gave him a reproving look. "You really should have warned us, sir."

Lewis ran down the hall. It was Marina all right, sitting on a stone bench, her back to him. "What the hell are you doing here?" he sputtered.

She turned her head. "It's good to see you, too, brother. The roses here are lovely, don't you think? Not a variety we have in Grantville."

"I mean, how could you come without sending me word, giving me the chance to tell you whether conditions were safe?"

"I did send you word, a few weeks ago. But then I had the chance, thanks to Duchess Claudia, to snag a seat on the Monster." That was the world's first commercial airplane. "You can't begrudge me having chosen to cross the Alps in just a few hours, rather than a month by land, can you? And then it was just a coach ride from Venice to Florence." She added impishly, "I'm sure my letter will get here eventually."

"Claudia de Medici? The archduchess and regent of Austria-Tyrol? How do you know her?"

"Why, she came into the store."

"Claudia de Medici visited Bartolli's Surplus and Outdoors Supplies?"

"No, she just pressed her face against the window glass, idiot. Yes, she came in. It was refreshing to have a visitor who asked questions about things that didn't go boom. We hit it off."

Lewis stared at the ceiling. "I don't suppose she asked about our family, too?"

"Oh, yes, I bragged a bit about our brother-in-law." Greg Ferrara, once Grantville's high school chemistry teacher, and now the USE's Grand Poo-Bah of Military R&D. "And I might have mentioned Toni Adducci, Senior." He was their first cousin, once removed, and the Secretary of the Treasury for the State of Thuringia-Franconia.

"Good God, Marina, you were talking to a Medici. For them, there is no boundary between family life and political life. I wouldn't be a bit surprised if she knew about Greg before you opened your mouth. She flew you to Venice—"

"And arranged for me to be escorted here. And I have a letter to her nephew Ferdinand, asking that he see to it that I am safely returned to her townhouse in Venice when I am done here."

"How nice. Given that 'nephew Ferdinand' is the grand duke of Tuscany, I am sure you'll travel in style. But what sort of favor do you think Claudia will expect from you? And what will she do if you can't deliver?"

"Oh, pooh," said Marina. "I can deliver. I already had cousin Greg and Archduchess Claudia over for dinner, for example. It went fine, even if Mother nearly had a nervous breakdown. And I can ask my brother Lewis—" She winked. "—whether there might be any 'investment opportunities' in his boric acid operation. So, are there?"

"Given that the operation is backed by Medici money, and Claudia is a Medici, I think that's a safe assumption."

"Good. I also have a list of chemistry questions for you. Mind you, I think Claudia already put the same questions to cousin Greg, and just wants to see if your answers are the same. She's a smart cookie."

"I'm sure."

"She kinda hinted that she might be able to take me on as one of her ladies-in-waiting."

"You want to be a glorified servant to a noblewoman?"

"Oh, that's right. I could stay in Grantville and be a sales clerk in a sporting goods store. What was I thinking?"

"Still—"

"Okay." She held up her left hand, palm up. "Sales clerk in Grantville." She held up her right hand the same way, at the same height. "Lady-in-waiting and ornamental up-timer in Tyrolia." She jiggled the hands up and down, as if they were the pans of a balance, then suddenly raised the left and lowered the right, sharply. "Tyrol wins!

"Anyway, you're one to talk. Isn't 'nephew Ferdinand' your patron now?"

"Technically speaking, he, and his brother Leopold, are patrons of the Academy, not my personal patron. I am still an officer in the USE Army."

"Technically speaking, 'Mister Consulting Detective,' if he tells you to piss, you say, 'yes sir, how far, sir?' Because we want Tuscany to be a friendly neutral. At least, that's what the Ambassadress told me when I passed through Venice."

Lewis winced. "As a matter of fact, he has given me a little assignment. A murder investigation."

"Ooh, tell me more."

* * *

"Well, the gruesome part is done," Lewis said. After the grand duke's physician had clucked-clucked over the corrosion of the stomach lining—typical of arsenic, antimony or mercury poisoning—Lewis had divided the stomach contents into two parts. One part he preserved intact, for study under the microscope, and the other part he homogenized, acidified, and heated. He let it cool back down, and ran it through a filter.

"Your Grace, if there is any arsenic in the filtrate, it is now sodium arsenate. We can now perform the Marsh test." Lewis pointed at a bottle. "That contains arsenic-free sulfuric acid." Lewis pulled some small rods of metal out of a chest. "And these are arsenic-free rods of zinc metal; what the alchemists call 'Malabar lead.'"

The World's Most Blue-Blooded Lab Assistant, otherwise known as Grand Duke Ferdinand, put the rods into a flask and poured the acid over the metal.

"Take it easy, Your Grace," warned Lewis. "We want to keep the temperature low, and the evolution of hydrogen slow." Lewis stuck his precious up-time thermometer into the flask. "Hmm . . . you were perhaps a little too enthusiastic. Let's cool things down a bit." He put the flask into a dish of cold water for a few minutes, then removed it.

"All right, next step." Lewis stoppered the flask, and inserted two tubes into it, one for adding the sample at the proper time, and the other to a U-shaped drying tube. This in turn he connected to an L-shaped tube with a long arm passing over a candle.

"Now we wait for all the air to be expelled."

The minutes passed.

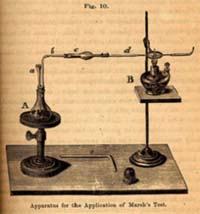

Leopold fidgeted. Finally, he asked, "Why is it called the 'Marsh test'? That is your English word for a 'swamp,' si?"

"It's named after the English chemist, James Marsh. Marsh was called upon in a case in which a young man was accused of poisoning his grandfather with arsenic trioxide . . . that's what your apothecaries call 'arsenic.' He detected it by its reaction with hydrogen sulfide, but by the time of the trial, the yellow precipitate had deteriorated, and the jury refused to convict. Marsh was apoplectic over this miscarriage of justice, and worked long hours in his laboratory until he devised this test."

"Why the zinc?"

"The zinc reacts with the sulfuric acid to generate hydrogen, and the hydrogen reacts with the arsenic to form arsine gas."

"A gas? Like air?" Leopold, clearly, had attended Lewis' lecture on how air was a substance. "How will we see it?"

"When the gas is brought to a red heat here"—Lewis pointed to the part of the tube right above the alcohol burner—"it will decompose into metallic arsenic and hydrogen, and a shiny black deposit of arsenic will be deposited on the inside of the tube, just beyond. That's what we call the . . ." He paused for effect ". . . 'arsenic mirror.'

"It is time. Leopold, would you like to do the honors?" The World's Second Most Blue-Blooded Lab Assistant dropped the filtrate down the sample tube into the flask. And his older brother lit the burner.

"I can't believe you're letting them do everything," Marina complained.

"I thought you hated lab work when you took chemistry last year."

"I did. But you still should have asked me."

"I don't see anything yet," said Ferdinand.

"Let me see if this helps." Lewis held a white paper behind the tube.

"No. . . . Wait . . . yes! I see a brown stain."

"It's getting blacker," said Leopold.

"Black as sin," pronounced Ferdinand. "We have a poisoning, don't we, Lewis?"

"It looks that way, Your Grace. But let me confirm." Lewis brought the burner to the free end of the tube, and ignited the escaping gas. It produced a bluish white flame, with white fumes.

"So far so good. Or bad, depending on your point of view."

Lewis held a cold porcelain dish to the flame, then brought it away. There was a brownish black spot upon it. "And that, my friends, is the 'arsenic spot.'"

* * *

Marina walked into Lewis' house, followed by a servant trying to balance a large pile of goods.

Lewis eyed the pile warily. "I hope Archduchess Claudia gave you an expense account."

"Nothing to worry about, brother. These are gifts from relatives."

"Relatives?"

"You didn't think that the Bartollis climbed out of the trees in West Virginia, did'ya? There are Bartollis right here in Florence. Cosimo, Lorenzo, Giovanni, Matteo, Niccolo, Piero. . . ."

"And you think we're related, just because of the last name?"

"Well, they thought it was reasonable. Of course, they weren't sure of the blood connection until I mentioned that I had been in Ferdinand and Leopold's private laboratory, and flew to Venice with Archduchess Claudia."

"You impudent namedropper, you. Even if it's true, let me think . . . 370 years . . . twenty years a generation . . . you might be their cousin eighteenth removed, if I've got the terminology straight. You're probably more closely related to John F. Kennedy than you are to them."

"Whatever. So, who d'you think knocked off Pietro?" Marina said.

Lewis laughed. "Suspects? They are as common as mosquitoes in the Maremma. Silvia is sure it's some business or political rival. She gave me a list. Pietro was recently appointed to a salt magistracy, and she thinks that perhaps he discovered that one of his colleagues was embezzling funds, and threatened to inform the authorities if he didn't turn himself in."

"More likely asked for a cut in return for his silence, and got too greedy," said Cosimo.

"But were those rivals at the dinner?" asked Marina.

"Even if they weren't there, they could have suborned a servant," said Cosimo. "But actually, I think it's the wife. Wives have poisoned inconvenient husbands since time immemorial. A half-century ago, Bianca Cappello, the most beautiful woman in Tuscany, poisoned Pietro Bonaventuri, so she could marry her lover, Francesco de Medici."

"Yep, Silvia's a suspect, all right. Silvia would have much more financial independence as a widow, and she's still good looking. For that matter, perhaps there's some young fellow she already has her eyes on."

"We'll look into it," said Cosimo.

"Then there are the heirs," Lewis continued. " Domenico and Olimpia . You do know what they call arsenic in this day and age? 'Inheritance powder.' It can be added to food or drink without imparting a suspicious color or taste, and seventeenth century alchemy is quite incapable of identifying it. That made it the ideal poison until chemistry caught up with the poisoners in the nineteenth century."

"Rocco got chummy with Taddeo, found out that Pietro's got a mistress. Had a mistress, I should say. Her name's Stella. Lives at a nice address, dresses well. Sin pays."

"Ah," said Lewis, "the plot thickens. Or, more precisely, the list of suspects increases."

Marina looked unconvinced. "Why would she kill the goose that lays the golden eggs? Surely she would be left with nothing if he died."

"Right," said Cosimo. "Usually the mistress gets rid of the wife, and marries the husband. Bianca Capello did that, too. Remember her? She poisoned Giovanna, the Austrian princess, and married Francesco de Medici."

Lewis shrugged. "A mistress might murder a patron. Perhaps she found a fatter 'goose,' and Pietro wouldn't let her move on. Or perhaps he beats her, and she wanted revenge. Or he refused to divorce his wife, and she decided to poison Pietro and hope that the death would be blamed on Silvia."

Marina had a different idea. "Or perhaps some young fellow is madly in love with Stella and killed Pietro out of jealousy."

"You're quite a romantic," said Lewis.

"No, no, your sister's right," said Cosimo. "That sort of thing happens. I'll ask around."

"Perhaps I should interview this Stella myself."

"How very conscientious of you, dear brother."

* * *

Cosimo found Stella's boy toy. "His name's Fabio," Cosimo reported.

"Occupation?"

"Artist."

"Great, all I need," said Lewis.

"What's wrong with artists? Even artists named 'Fabio'?" asked Marina.

"The pigments they use. Which include realgar red and orpiment yellow. Realgar is arsenic (II) sulfide, and orpiment is arsenic (III) sulfide."

"While those are poisonous, you can't put them in food without anyone noticing," said Cosimo.

"But you can react them with natron, sodium carbonate, to get arsenic trioxide. And heat that in vegetable oil if you want pure arsenic. As I said, all I need."

Lewis started pacing, then stopped abruptly. "Although while this Fabio may have had the means, and the motive, I am not so sure he'd have the opportunity. When would he come into contact with Pietro?"

"Perhaps he gave the stuff to Stella to administer to Pietro. He might not even have told her it was poison. Perhaps that it was an aphrodisiac."

Lewis snorted. "We're making quite a mountain of accusations out of a molehill of evidence."

* * *

Lewis knew that Pietro's body contained a large dose of arsenic, the Marsh test on his stomach contents was ample proof of that. If the arsenic had been administered on the day of the infamous dinner, then the list of suspects could be trimmed down, to just the family, the guests and the servants present that day. Still a long list, of course.

But Pietro and Silvia thought that there had been a series of attempts on his life. And if that were the case, and they were all by the same party, then knowing when the attempts were made could help narrow down the list of suspects.

Unfortunately, the Marsh test didn't provide a timeline. The statements collected by the investigators, and even the household account book, hadn't been of much help, either. There were payments for medicines, but the responsible doctors and apothecaries swore that these didn't contain significant amounts of arsenic, and Lewis' testing of the remaining vials, ointments and whatnot confirmed that. In fact, it seemed that Pietro had the least chronic exposure to arsenic of anyone in the household.

Lewis had one last resort. Back in 1997, the high school had been the recipient of an extraordinary gift, a $300,000 atomic absorption spectrophotometer. The gift had come about because one of the high school teachers had led a statewide high school science club trip to Carnegie Science Center in Pittsburgh, and had run into some LaFarge executives there.

As the name suggested, the AAS atomized a sample and then analyzed its ability to absorb light of different wavelengths. It should be able to detect arsenic at a level of just one part per million. Perhaps less.

"It's been a month since Pietro died, Dottore," Ferdinand said. He and Lewis were sitting in Ferdinand's laboratory, a corner of which had been appropriated by Lewis. "Can this wondrous AAS of yours still find the poison?"

"That's the good thing about an elemental poison, like arsenic, or thallium, your Grace. The body can kick it out, but it can't decompose as it can, oh, snake venom. Within an hour or two of ingestion, the arsenic is distributed all over the body, even in the hair roots. Within a few days, it can be detected in the hair above the skin. And if the victim died with arsenic there, it will be still be there a month, a year, a decade, even a century later. The arsenic atoms stick very well to the sulfur atoms in the hair."

"A century, are you sure?".

"That's right. In the nineteenth century of the old time line, there was an emperor of France named Napoleon. He got defeated by the Brits and sent into exile on an island. He died there, and some people thought he had been poisoned. Over a century after his death, someone took a lock of hair that Napoleon had given to one of his aides, and had it tested with modern equipment for arsenic.

"Sure enough, he had way more than normal levels of arsenic."

"Wow!" said Marina, who had been invited to look at Ferdinand's chamber of curiosities. "Napoleon was poisoned!"

"Well, not necessarily deliberately," Lewis admitted. "There was a green wallpaper used at that time, which contained an arsenical dye. They didn't know that it could be decomposed by bacteria to release arsine gas, which is really nasty stuff."

"A hundred years . . ." muttered Ferdinand.

"I beg your pardon, Your Grace. What did you say?"

"Never mind that for now. You already know that he was poisoned, from the contents of his stomach, so why look at his hair?"

"Because the hair would chronicle his arsenic exposure. Hair grows from the root outward, at a rate of a centimeter a month. So if his hair were twelve centimeters long, we could cut into sections and know when he ingested arsenic over the past year or so."

"Marvelous. And so you could eliminate any suspects who were absent when he had an arsenic peak," said Ferdinand.

"Exactly."

"Would you know the very days of each poisoning attempt?"

"I wish. To narrow down the time, you need to test shorter segments of hair, and there is more of a chance of contamination of the segment with arsenic from other sources. And that one centimeter a month is an average, it varies from person to person, and even from one part of the head to another. But we should be able to pin it down to a particular month, maybe even a particular fortnight.

"While I'm at it, Your Grace, I would like to send Grantville some additional hair samples for testing. My hair, Marina's, Cosimo's and your own, perhaps. We'll make sure that no one is putting arsenic in your soup, that way, and the rest of us will act as controls."

"See to it. Tomorrow morning I will have a courier take it to Venice. It can be there in two days, and then catch the next flight to Grantville. And your colleagues can radio the results to Venice to save time. All I ask is that the communications not reveal anyone's names."

"I wouldn't want them to. I will number the hair samples, so the testers won't be influenced in any way."

* * *

"These results . . . are very strange."

"How so?" asked Marina.

"Okay. Look at the report. Sample 1 is your hair, that was the main control."

"Why not your hair?"

"Well, since I've been in Italy for a few months, and I have made few enemies, I couldn't be sure that no one was poisoning me."

"Oh."

"Anyway, your levels are low. About one part per million. So are mine, and Cosimo's, and even the grand duke's, for that matter. All under five parts per million. But now look at Sample 5."

Marina stared at the graph. "That's weird. They're up and down, on a regular basis. But . . . the peaks get higher and higher. And then the last peak is way up. So what does it mean?"

"First of all, these peaks are way above what a seventeenth-century Italian would naturally be exposed to. So Pietro was being poisoned all right."

"Which I thought we knew already, from the Marsh test on his tummy-wummy."

"Yes, Marina, but it was nice to get that confirmed by a more sensitive test.

"Second, Pietro suffered both chronic and acute arsenic poisoning. Which means that either our poisoner kept notching up the dose, and finally got impatient for some reason and hit him with the chemical equivalent of a two by four . . ."

Marina finished his thought. "Or we have two poisoners, working independently."

* * *

"Cosimo, I need to construct a plan of the house," Lewis said.

"What good will that do?"

"When a general is planning a battle, he consults a map of the terrain, does he not? When a detective investigates a crime in a house, he needs a house plan."

Cosimo shrugged. "All right, that makes sense. Perhaps I can borrow an assistant from one of the grand duke's architects; he'll do a better job than we could."

"Fine, Cosimo, but I need exact dimensions, not just a general layout. I want the length and height of every wall measured, and every corner checked to make sure that it's a right angle. I want to know the apparent thickness of every wall, beginning to end."

"You're looking for secret rooms?"

"Yes, like the priest's holes the Catholics in England have. Or even just a little hiding place."

* * *

"There, Cosimo, just as I thought. The dimensions of the study aren't right. This wall should be a foot further away from the windows, to match the next room over."

"So what does that mean?"

"A false wall, and something behind it." Lewis put his ear against the wall, and tapped it.

He then did the same for one of the other walls.

"I believe the far wall is hollow. You try it."

Cosimo did just that. "I guess we need to go get some axes," he said cheerfully. The thought of a little authorized mayhem, even directed against the inanimate, was apparently pleasing to his martial spirit.

Lewis rubbed his chin. "Let's not be hasty. If the secret compartment, or whatever, was accessed frequently, his lordship certainly wasn't bashing in the wall each time. Start feeling around for a hidden panel."

They found it eventually, just below the ceiling. It had been superbly designed; it was no wonder they hadn't found it the first time they searched the house. The compartment it concealed wasn't that big, but it was big enough to hold some oddly marked vials, and a journal. Lewis handed them down to Cosimo, then stepped off the chair.

One of the vials contained a white powder. Lewis pointed to it, and Cosimo handed it over. Lewis pulled out the cork, and waved his hand over the top, wafting the released air toward him. "I'll have to test it, but I think it's arsenic. I wonder what the book says."

Cosimo had already started leafing through it. "Makes no sense to me."

"Here, let me. After reading the Latin mumbo-jumbo the alchemists write, I am pretty good at understanding esoterica. Not to mention reading really bad handwriting."

Cosimo handed the book over, with a slight smile.

"Why are you smirking, Captain? Oh." The text was clearly encyrypted. "I guess I'll save that for later."

* * *

Lewis had taken the first steps to solving the secret text. First, he tabulated all the symbols used on the first few pages. There were 26 different ones, which implied that each stood for a letter of the Renaissance Latin alphabet. It was just what Sherlock Holmes had done in "The Adventure of the Dancing Men."

However, Lewis couldn't be sure whether the cipher was in Latin or Italian, and in any event, Lewis didn't have frequency tables for either language. That problem was easy enough to solve; he gave Cosimo and Marina a few texts in each language, and had them compile tables for him.

In the meantime, he made a frequency table for the cipher. He was relieved to discover that it seemed to have the characteristic look, in terms of variation in frequency among the letters, of a monoalphabetic substitution cipher. That is, one in which each letter of the plaintext was replaced with a single cipher letter, and always that letter. Lewis had read that polyalphabetics had been invented in the fifteenth century, and wasn't at all sure that his deciphering skills were up to tackling one.

"Here you go," said Marina. "I hope this is based on enough data. I'll go blind if I look at any more Latin gobbledegook today."

Lewis looked it over. From most to least, it ran E A I T U . . . English would be E T A O N . . . Fortunately, with so much cipher text to work from, it would be easier to solve than even a newspaper cryptogram. Assuming that Lewis hadn't made any mistakes in converting the symbols into letters, and that Pietro, or whoever, hadn't thrown in too many nulls, abbreviations, code names or mistakes.

Marina looked over her shoulder. "I can tell you what it says. 'Dear Diary'. . . ."

"You're right, Maria, it is a diary. Although each entry begins with a date. So I will decipher the first few entries, and then switch to the last ones."

"Fine. I am going out."

"Okay, you know the drill. Summon the coach, have them wait for you, don't go off with any strange men. Actually, with any men."

"Yeah, yeah." She gave him a vague wave and went looking for a footman.

Lewis went back to work. He was still working when she returned, late in the evening. But he was able to tell her something important. The text wasn't a diary, exactly. It was a journal. An experimental journal.

The next morning, when Cosimo arrived at the door, Lewis was waiting for him. "Cosimo, we need to visit a few apothecaries," said Lewis. "Oh, tell Carlo and Rocco I would like them to dress as servants, not soldiers. We are going to collect information, not to make arrests. I'll explain along the way."

* * *

"I understand you have solved the mystery," the grand duke declared.

"I think so, Your Grace. Pietro poisoned himself."

"Suicide? That is a serious charge—"

Lewis held up his hand. "Forgive the interruption, but while the poisoning was deliberate, the result was accidental."

"Explain."

"You will recall the testimony of the Lady Silvia that Pietro thought that someone was poisoning him. He questioned and fired a few servants, but of course he then had to hire new ones, who he soon suspected in turn. In desperation, he began his experiments."

"Oho," said Leopold, "he emulated Mithradates."

"Who's Mithradates?" asked Marina. "The name sounds Greek, not Italian."

Leopold smiled at her. "Mithradates of Pontus. He fought three wars with Rome. He was afraid of assassination, and he protected himself from poisoners by taking tiny doses of many different poisons. Then when he was about to be captured by the Romans, he tried to poison himself, without success. Had to ask a friend to run him through with a sword. See, brother, I wasn't sleeping during my history lessons."

Ferdinand pretended to yawn. "That's what you did at least once a lesson, and you sure looked like you were sleeping. I guess you came awake if you heard the words 'poison' or 'sword.'"

"The infamous 'auditory echo,'" Marina muttered.

Lewis coughed, and Ferdinand motioned for him to continue. "Pietro took arsenic in small doses. Probably every other month, which is why the arsenic level in his hair fluctuated the same way. And he kept increasing the dose, as his tolerance increased, which is why the peaks got higher and higher."

"But the big peak at the end—surely that was something different? A poisoner got through his defenses?"

"That's what I thought, at first. And I suppose I can't rule it out, completely. But his secret journal records where he bought his arsenic. On those mysterious solitary trips in disguise that Cosimo told us, I believe. Pietro usually went to Cinelli's. But this last bottle, he got it from Rossi. I'm not sure why; perhaps Cinelli was out of town."

"What difference would that have made?"

"A crime was committed all right, but it wasn't murder. I made tests on the arsenic in the secret compartment, and also bought arsenic from both Cinelli and Rossi directly.

"Rossi's arsenic was fine. Cinelli's, on the other hand, was, excuse my French, crap. I think Cinelli was adulterating his arsenic all these years, and Pietro never realized it. Rossi, on the other hand, was an honest man. When Pietro bought arsenic from him, it was pure stuff. Consequently, Pietro received a much greater dose than he was expecting."

"Deliberate, yet accidental," murmured Ferdinand.

"Exactly."

"Captain Cosimo, see to it that Cinelli is arrested for criminal adulteration. I will tell Silvia that she and her son are now free of suspicion, and there will be no interference with the disposition of the estate."

Cosimo saluted, and left the room.

"Oh, Dottore Bartolli. I am most gratified with your work on this matter. But please, while you are welcome to mention your Marsh test in your lectures, please say nothing about the ability of this atomic absorption spectrophotometer in Grantville to detect arsenic in even a hundred-year-old corpse. At least, not to anyone other than a member of my family."

"Yes, Your Grace."

"There is going to be a party at the palace, I hope you and your sister can come," said Ferdinand.

"Yes, please come, Marina," said Leopold. "You can tell me more about Grantville. Do you know how to dance the gagliarda?"

"No, but I can teach the macarena."

"It sounds like you had a most interesting visit to Florence," said Archduchess Claudia de Medici.

"Indeed I did, Your Grace," said Marina. "But, why didn't your nephew Ferdinand want Lewis to talk about the AAS. Wouldn't he want to discourage future would-be poisoners from practicing their art in his realm?"

Claudia laughed. "Oh, yes. But it's the past he was worried about."

Marina looked blank.

The archduchess leaned over, and whispered her explanation. "You haven't heard the story? In 1587, my Uncle Francesco and Step-Aunt Bianca"—she carefully enunciated the "step"—"both suffered a sudden illness. Francesco was the grand duke at the time, Papa being his younger brother. Fortunately, Papa had arrived at the villa a few days earlier. He took charge, seeing to it they had the best possible care.

"Alas, they died eleven days later. The grand duke's death was, according to Papa and his physicians, because of Francesco's terrible eating habits. And Bianca's grief was too great for any mortal to bear, so she died the same day. From the stress of watching Francesco's decline, no doubt. The autopsies confirmed that the deaths were completely natural, and Papa bowed to the inevitable and became the next grand duke. Ferdinando the First. His first son was my older brother Cosimo, who fathered Ferdinando the Second.

"Anyway, certain rash and unprincipled people have nonetheless suggested that the deaths came at a too convenient time for Papa, Bianca having been maneuvering to have her bastard Don Antonio declared the heir. The word 'poison' was trotted out. It is really annoying, the way people think 'poison' as soon as you say 'Medici.' We aren't the Borgias, after all.

"It is possible that someone unhappy with my brother's rule might agitate for this AAS test to be performed on the bodies of Francesco and Bianca. If the results were anything but unambiguously negative, then they could be used to question the legitimacy of Ferdinando's rule."

"But wouldn't your nephew want to know whether they were poisoned?"

"God knows already, dear Marina. Just God. And it's better that it stay that way."