To John Paulet, Winchester

To my good friend John, and to your lady wife Jane, we congratulate you at the glad news of the birth of your first son, Charles. We hope both mother and child are well, and his auspices are favourable.

John, Mary and I have heard of last year's Parliament from my lord Francis Russell, earl of Bedford. From the problems in your last note in June, we have been concerned for you both, it is hoped that outgoing expenses during your attendance as a Member in London were not extreme, and recovery of your estates continue. We had not expected your father's past entertainments would be covered by the banks to such an extent, nor the reports in the London papers to bring such unwelcome public revelations on his death.

On a happier note, I must let you know your visit to London has also caused trouble in the Weasenham house. We hear an ode to your wife's presence and beauty at Court is published by that Cambridge upstart John Milton, and is available in his latest collection from publishers in the Strand. Mary has asked, in jest hopefully, how I might commission one for her. No trips to London for us I think, but now must take her with us to Hamburg to shop whilst my Uncle and I arrange future trade.

However, mainly I write of the King's Commission at Lynn this past week. Attending on behalf of our family's trading and estate interests, my brother and I heard that the proposal from the king's embankment engineer, Sir Cornelius Vermuyden, to drain the Great Fen has finally been agreed at the Privy Council, but in detail I have some surprising news.

Lacking capital to the satisfaction of the Drainage Commissioners, Vermuyden is no longer undertaker of the venture. Representations (and, we are sure, some monies) from attending landowners persuaded the commissioners that further capital is required to complete the works.

After the deaths and riots at the works at Aldeney Island and Hatfield Chase, the cases still in the Lincoln court against the king rumble on. We witnessed at the meeting many, including a spectacular oration from a Cambridgeshire squire, Cromwell, ranting on for an age about the "ancient rights of pasture and hunting on common land by god fearing fen-men being denied and ignored by land hungry foreigners." Much upset was displayed during the meeting, and the commissioners adjourned for a third day for overnight discussions with the major landholders and the bishop of Ely.

In reaching agreement, and to avoid further legal complaints, the Cambridge and Norfolk shire lords and landowners must now lead the enterprise. Francis Russell is now the undertaker, his holding of Thorney being the largest property affected by the scheme. He has promised ten thousand pounds capital to the corporation, with the expectation of retaining forty thousand acres to improve his holdings and a further ninety thousand pounds promised for the corporation from the other investors.

As you know Francis' estates in the east have not returned well without direct access to the king's highways or to port. With the new land, and an open aspect, he has boasted he now retains the architect Jones to rebuild Woburn Abbey as his family seat, and from whence he may manage his holdings and travel to London as needed.

For my family, a new great drain for the River Ouse from St. Ives to Downham Market shall cut somewhat through our lands at Hilgay, but we expect equal replacement, and are promised in writing an addition of five hundred acres from reclaimed sections for assistance in canvassing parish landholders and using our family links with the town council at Lynn to agree the plans.

Vermuyden shall continue in the syndicate as works director, and other English and Zeeland connections are also promised their own land grants at the end of the task, to the satisfaction of the commission. Ten thousand men to labor are expected, preference now offered to local men, then Protestants from the Spanish Netherlands and lastly from the Dutch Provinces.

The Commissioners shall sponsor an Act of Parliament, "The Lynn Measure." If the works can keep the designated land clear for two consecutive summer growing seasons by 1638, then parcels and land grants shall be allocated. If not, the Company must bear the brunt of all capital costs, with no recourse to the courts or the king. Let us hope this is an end to open envy speculation, and with a clear relationship between a man's effort (or capital) over seven years, and the resultant land assigned to him.

At market, the grain harvest is good and fine this year, however prices are still depressed below last. In our eastern counties landowners are attempting other alternatives from the Gardeners' Company. Grain is hardly profitable, and in many places in Norfolk is grown only to feed the families idling on estates. We understand in the southern counties you have similar experiments, with George Bedford working to producing the dye madder for the first time outside the Low Countries.

Baltic grain does not land; most is diverted to the Germanies via Hamburg, and we expect none for some time. Our farmers with small plots are now completely dependent on any local surplus from market in good harvest years. We expect hunger, suffering and death when the dice rolls the other way, which it must.

Sufficient timber arrives from Sweden and the Pole's lands at our yards at both Lynn and Wisbech before the winter gales. I shall include this note and packet with the final shipment of Polish oak beams to the Cathedral School at Winchester, via Southampton, and hope it reaches you before the end of the year.

Lastly, my father has asked to enclose samples of good seed on trial from the Gardeners' Company in London, with directions on handling. He asked that you attempt them on your lime soil at your estate in Southamptonshire, as we do not think of them well in our peat, nor do we have space apart from our part of the ongoing woad experiments for the Dyers Company.

Be well with God my friend, and do let us know if there is anything further we can do to assist in balancing your estate debts. As usual, we shall keep an ear to the news coming our way from London, from the Germanies and Baltics, and shall share anything to our mutual advantage.

Your Servant,

Robert Weasenham

"Can you remind me again why I'm freezing my arse off on this god-forsaken mission of yours?" grumbled a faint voice thru the driving sleet, from under a wet fur hat.

"Oh, the usual when dealing with the London Companies—connections, bribery and profit, especially the bribery and connections," Rob shouted back through the wind.

Tom Cotton was a city boy in his late thirties, and not a great traveler. "I'd rather be in a gaming house in London at this time of year, not plonked on the back of a bony nag in bad weather. Or at least give me a coach with soft pillows, and a curtain to keep off the wind."

As the mission leader, Rob Weasenham was enjoying his cousin's discomfort, watching his companion hunched unhappily on the horse in front. Tom had always been a bit of a fashionist, too much time dressing up at Court, not enough in the fresh air. Their small trade party was well covered with guards, but they needed to move quickly to avoid the worst of the winter.

"Let us hope the next change of horses is an improvement," Tom muttered.

"Take Tom, you'll need someone who knows books" a friend in London had suggested. "He's been a miserable git, moping about town since his father died." Well, Rob had him now, but he could have done without the constant whining about the weather, mud on his fine clothes, traveler's rations, rotgut wine, and a hundred other complaints through Dover, Calais, Paris, and parts east. And now diverting further south was wasting valuable time, and costing more than Rob had expected, the Swedish armies had taken the Rhine/Main junction at Mainz last year, and that route was reported as still not safe.

"Another hour, we should find the inn. Soon, Tom; another hour and you can drink yourself silly with some hot wine." Rob resigned himself to another bad night shepherding his investment, and an expectation of another thumping head in the morning. His cousin's drinking had always been a bit free in Oxford, but he'd settled down when he'd married Margaret, and running the estate at Connington. Taking on his father's responsibilities last year had been a bit of a shock, but what do could you expect when the king put the old man in the Tower over winter? Rob had not spent time with Tom for a few years, and was tired of dealing with a relation continually looking for answers in the bottom of a glass.

But the bulge under Rob's coat with the packet of letters from London was a constant reminder of the opportunities for, at least, some major favors awaiting back home.

Most of the letters and lists were due to connections in the City, mainly flapping tongues in trade halls and the Exchange in the City. The Apothecaries had started it—"Dr. Harvey has promised some seeds to a Master Little for a physic garden, and we must have some cannabis from Mr. Stoner."

It went from there to the Mercers—"find any almanacs, especially information on harvests and the weather." "Riiiight," Rob thought. "Try to fix the price of grain for the next twenty years." Rob and his uncle didn't believe those London pedants had thought through that more could be made playing the European shipping insurance market to best advantage with the same information.

Next, the Gardeners' Company chimed in—"we have heard Grantville plants cabbage, squashes and other Dutch crops in the way of our market gardeners. Record growing methods, and any seed varieties. We also have been unable to grow potatoes well, unlike Ireland. Do they have some that would suit England?"

And the Silk Makers—"if this place is truly from Virginia in the Americas, search for Red Mulberry trees, as the seeds and cuttings from Jamestown have not served us well from long ocean voyages. Mayhap seed available closer to and planted earlier shall be more palatable to our silk worms."

And the rest. Rob carried wish lists from all the other London Companies, wanting an English merchant with active trade contacts in Thuringia.

The court was in quiet turmoil, but for once the palace birds were not squawking and little of the king's intentions were known. Concerned at the rumors, his worship the mayor of London, had arranged a secret Companies meeting in the Guildhall, along with the professors from Gresham College for advice on what to do next. London's trade must not suffer, and when money was at stake, when did the City and its merchants wait for guidance from any king?

His old Oxford college friend—now a professor—John Greaves had therefore suggested the Weasenhams at Lynn for an off-the-books visit. The Dyers Company also had connections to Erfurt from ten years before because of Rob's uncle William supplying German woad plants and extraction methods to various landowners in an attempt to make England self-sufficient in the blue dye.

So here Rob was. October and November in the rain with a grumpy cousin, the license to travel to Grantville that had been much harder to obtain than anyone would believe, and a pocket full of wild expectations. He had hoped to use the existing relationship with Erfurt as an excuse to travel, but the French were having none of it. He and Tom were both taking a calculated risk to get to Grantville before winter set in, and get out before any more roving armies attempting to flatten it the following spring arrived.

Another note that had caused them to be on their horses in filthy weather was sitting safely in a desk at home. Stark bribery! Uncle William had judged the risk and that had tipped the balance. Rob and Tom were to go to Grantville.

To Master William and Journeyman Robert Weasenham, Hilgay, Norfolk

Most Private and Confidential

Sirs,

Professor Greaves was kind to mention you have agreed to visit Thuringia and Grantville for his worship, the mayor. May I also ask to add a charge of my own, and to your family's benefit?

With the new tasks in the Great Fen, and developing Covent Garden in West London, I have secured against all capital and a percentage of my rents for next years. My fellow investors must know if our intended endeavors succeed, and what troubles to avoid on the way.

There have been mentions of a great "English Encyclopedia," and other history books in the Grantville Library that is open to all that come. It is hoped that somewhere an indication of the result of the Lynn Measure in six years shall be recorded.

As for Covent Garden, I continue to be exasperated. Our king demands beauty in design and form, but it is not his monies at risk if I may not find tenants. Acquire a selection of some building designs from Grantville suitable for his majesty's approval, and any plans that shall help my agents in London to keep my bankers at bay.

If you can find what you may before summer next, the Levels Corporation shall add five thousand acres to your family's allotment at the Isle of Southery from Mr. Lien's piece.

Robert, I have also contacted your cousin Thomas, and in confidence have encouraged him to travel with you. He is still not attending to business and is continually in his cups in town, and gambling heavily since your godfather, Sir Robert, passed. Thomas now holds the largest library in England and should be certain to sift information wanted by the London Companies and myself, for you were never one inclined for the books unless it contains a column of numbers. If we can include him a part of this mission and under your direction, mayhap the cloud may be lifted from his countenance.

In your debt,

Francis, Baron Russell, Earl of Bedford

Thomas removed his hat and strode into the double doorway of the Grantville Public Library. His cousin was off doing more deals for the day, but Tom had reassured him this was not yet the right time to be exploring through the book collections in this wonderful place. Tom knew that when visiting another's library he should arrange to impress the owner or sponsor first with a few gifts.

"My bailiwick, I think," he had assured Rob, and then left their lodgings at the schloss above the "power plant" on his new horse earlier this morning. He then headed back down the new road into Grantville in the snow.

Rob and Tom had tried the previous day to negotiate with the town council, but it seemed that in Grantville the Milady Head Librarian was God Almighty in her bailiwick, and the governor of this town had little to do with arrangements and policies for access to the book collection.

Once inside the building, Tom handed his cloak, hat, and silver tipped walking staff to the elderly guard inside the library doorway. Some things might change, but some were reassuringly familiar. A sharp-eyed pensioner watching the comings and goings like a hawk in the entrance was exactly what he had expected.

Cecelia Calafano was standing behind the main desk, sorting—not very enthusiastically—through today's batch of newspapers and magazines from the re-cycling ferrets. Most of the textbooks had moved to the high school, and the deep reference section shelves were just the right depth to be stacked flat with newspapers and magazines by year, month, and edition.

She looked up when the door opened and suppressed a groan. The approaching well-dressed figure was unwelcome. Nearly all the new library visitors were directed to the high school, and Cecelia was not in the mood to deal with anyone.

"Chandler Bing in black velvet, a lace shawl, and pointy shoes." That was the first thing that came to her mind. She suppressed a snort, attempted a straight face, wiped her nose with a handkerchief, then began to put a flea in his ear using her improving German. "You will want to go to the school . . ."

He cut her off in perfect, formal English. "Good day, Madam. I have come to make introductions and would arrange a meeting with Milady Marietta Fielder."

The man placed what looked like a map roll case on the counter, and handed over a parchment envelope with a finely gloved right hand. "I wish to converse with Milady Fielder urgently. Can you tell me when her duties may allow her to be next available?" he insisted.

Cecelia sniffed, blew her nose loudly into her cotton handkerchief, and wished someone would hurry up and re-invent a decent, fast-acting, twenty-four hour cold remedy. "Mrs. Fielder is off sick with the flu, and can't be disturbed. I'm in charge. What do you want?" She knew she growled at him; her headache, sore joints, and wheezy chest were beginning to really piss her off.

His unexpected response was, "In that case, good lady, may I view your index?"

The question jarred her into her fuddled head, making her concentrate. Her librarian's instinct started flashing little red stars—no, it wasn't just because she'd blown too hard into her hanky. Most of the visitors dived straight to the history books, technical manuals, and political novels. No one asked about the index first. It usually took at least three visits to begin to civilize them.

Cecelia, still not mentally quite there yet, thought of a question from college, which popped out. "And which cataloging and indexing methods are you familiar with?"

His answer had her and her new guest sitting in a chair in the back office ten minutes later, with some tea brewing on her small hot plate. Cecelia grabbed the phone and started dialing.

Marietta Fielder wished she were dead. Dead would be easy, dead would be warm and less painful. Every winter since she was a child she had caught the latest sniffle, cold, or exotic flu. Regular as clockwork for the past ten years, she'd made a point of getting her flu shot early November, either at the mall in Fairmont, or from the doctor in town. Most of the time it had worked, and winter wasn't as bad as it could have been.

This year was worse than 1969. This time it hurt. No shots, no Advil for the migraines, precious little lemon juice. But she was mobile—just enough that she could be left safely at home alone during the day.

Shuffle to the toilet wrapped in an old dressing gown and bunny slippers, cough and splutter back to bed. All that was available was Gribbleflotz aspirin and some peppermints. Yuck!

Shaking her head in disgust while standing was a visceral mistake. Marietta gasped, held onto the rail at the top of the stairs waiting for her vision to return and slowly worked her way back to bed, levering herself back slowly under the quilt.

A thrash metal rock band erupted from the phone next to her head. More vision loss in an attempt to grab the handset. "What'cha want? No respect for the dead?" the corpse moaned down the line

Cecelia was gabbling at her. Marietta could hear her also coughing, spluttering, and the odd sneeze, but still gabbling.

"Marietta, we have a visitor, from England, insisting that he wants to meet you, sniff," Cecelia chattered away. "He has presents and everything."

Marietta was sure there was a combined chortle, giggle and a wet snort in the middle of that sentence.

Cecelia looked down at the map roll emptied onto the desk between her and their visitor. She ran her hand over "A Mappe of Massachusetts Bay Colony for His Worship Governor John Winthrop" and a package of papers marked "Inventories and Maps of Plymouth Colony, 1621" that were signed by a Captain Christopher Jones.

"He's a walking, talking librarian's Christmas present." This time Cecelia lost it completely, and barked out a laugh. Oooohhhh! More sore ribs, but worth it.

Her guest stared, frozen, with goggle eyes, perhaps wondering what had gotten into this sniffling, grumpy lady with the stupid smile. She waved one hand, mouthed, "Wait."

"Marietta, do you remember your first term taking your M.A.? Indexing and Classification Systems . . . Middle Ages to Victorian?"

Now she was enjoying herself. Life at the libraries had been a hell for the past couple of years. It seemed that God was having a little joke with the last two qualified librarians (or was that first?) in this universe. "You have someone here who uses the Caesarean Library Index—ACCCDEFGJJNOTTVV"

Getting into it (and being a smarty pants to boot), Cecelia quoted by rote from her college days, " Augustus, Caligula, Claudius, Cleopatra, Domitian, Faustina, Galba, Julius, Justinius, Nero, Otho, Tiberius, Titus, Vespasian, and Vitellius."

Tom nodded sharply, a grudging smile on his face.

A short garbled mutter from down the line, Cecelia answered sharply, "No chance, the British Library won't exist for another one hundred and twenty years, before that . . . where did the British Library get the Caesars' Index?"

More waiting, and then Cecelia heard a particularly painfully sounding exclamation from the handset. Finally, Marietta was getting very close.

"No, not him. His son. Yup! His father died over a year ago." Looking directly into Tom's sad eyes, Cecelia proclaimed, "I have Sir Thomas Cotton from London right in front of me, proposing some kind of library exchange program with the Guildhall in London, the Bodleian Library in Oxford, and Sir Robert Cotton's Antiquarian Library at Connington Manor."

Tom was satisfied that his family's reputation for preserving books and manuscripts had survived.

Francis Russell opened the shutters of his reception room window, looking down on the fallow deer grazing on the lawn in the late afternoon sunshine. He tossed his satchel with the paperwork from London onto his oak desk, and sat back to light his favorite pipe; smoke curling gently to the ceiling.

The now not-so-secret mission to Thuringia had not yet returned when Francis was summoned to Blackfriars Palace in April. Wentworth had informed him he had traded all of the king's twelve thousand acre interest in the Levels Corporation to others: selected landowners, merchants, minor lords and barons.

A condition was that Francis was to keep the "New Men" closely involved in the project, out of London and away from court. No doubt Wentworth was playing chess games with information from the history books. And Vermuyden—him too: no speculating on the London market, no crazy ventures in mining, keep him and his out from under the king's feet.

At the time the offer was a gift from heaven. Real investors with capital were always preferable to King Charles Stuart, who was always glad to spend other people's money with the slash of a pen. After the ham-fisted affair at St. Ives with Squire Cromwell's family, the king's boast that he could govern well without Parliament was going very sour, and Francis was pleased he had severed all current financial ties with the court. His bankers had also indicated with an improved rate of interest, and had also accelerated payments for the building work on Covent Garden Square on improved terms.

Now his old childhood playmate, Robert Weasenham had come back—alone. To be fair, he had delivered everything Francis had commissioned, and more. Tom Cotton had died in Grantville from a hot winter fever; however his bookwork had mainly been completed with precise collation of information that indicated that the Lynn Measure would fail.

"Whilst clear on certain details, the histories indicate the Measure will fail due to bad weather, thus some of the ditches and dykes must fail during some winter storm in 1636 or 1637. The other landowners also complain that the drainage is insufficient."

Francis' own encyclopedia entries had recorded that King Charles had assumed the project after the failure in 1638, and the impetus to complete the works had been lost until after a civil war. It also suggested that in that other history Cromwell was the coming man, and he had supported the completion of the project during the 1640s. Cromwell was a prickly subject for Wentworth and the king. Francis knew well enough to stay away from that subject in London.

A page from a 1994 road map of England (What was a "rental car"?) and encyclopedia entries for the towns in the Fen area showed the revised works during the late 1640s and thereafter for the next three hundred years. Francis now knew that they needed another parallel drainage canal for the Ouse, changes to the outflows of both the Nene and Ouse, high tide retaining gates at the river mouths, flood relief reservoirs. The list went on and on and on. This warranted more capital, more men, and he still had only five years to finish. Francis shook his head in wonder. The existing investors and the New Men would certainly have enough to keep them full occupied, and Francis had decided to delegate the financial arrangements more than he usually liked.

And for himself—only eight years left to manage his affairs. God! Seeing your own life history written down would sear any man's soul. Robert had assured him that these "Americans" believed God had changed what was written by bringing Grantville to this time. Francis had huffed and puffed at Robert, especially not understanding the story about the butterfly, and dismissed it as a piece of whimsy. Francis was a practical sort of man, what was written is written. He had immediately updated the will and inheritance clearly onto his children.

He now had had only two available options to attempt to square his debts before his potential death in 1641. He played the arguments again through his mind:

Point the First: Covent Garden

Here the information was very, very good, especially for a developer. His original plans had finally turned out well it seemed, and his descendants had prospered as a result. Francis had leaked a little of this information to the London market, and waited for offers to assist in bringing his plans to completion.

The keys to early success were not housing and tenants as originally thought, but shops, arcades, and the concentration of specific trades. Booksellers and map makers on one street, tailors of high fashion on another and the vegetable and flower sellers concentrated in a single square. He would be damned if he would give them Covent Garden Square, and preferred its more profitable later use as a fashionable covered arcade for shops and dining. More work for Inigo Jones, after he finished the church on the west side.

He also enjoyed the idea of a sober theatre with large columns and retiring rooms on the north side. That would please the king, and his agents had already been approached with offers to fund and build it by the Mercers Company.

As far as Francis knew, Rob had bought the only copy of the "Central London A-Z" map. Therefore he had only changed one thing on his original street plan, renaming the newly assigned tailors street "Saville Rowe." No one would ever know the difference.

Covent Garden should bring in about three-quarters of what was needed, especially the idea of the nine hundred and ninety-nine year leases, and recurring land rents. Cobnuts to the Duke of Westminster, whoever he was!

Point the Second: The Great Level

This was going to be a little trickier. There was an obvious new source of capital: Dutch landowners and merchants salting their monies outside the United Provinces. Robert had similar concerns about the introduction of a flood of new residents to the Fen. So they had decided on a two-pronged approach

Set land aside near the existing towns for housing, to generate more land rents and increase the tithe returns for the towns and surrounding areas. Use the American style of building in "divisions," using a local developer to build town houses, shops, schools and amenities, and releasing them for sale in stages. In these ways new families, their retainers, and the merchants they depended on could be introduced gradually. If possible, grease the palms of councilors, and co-opt the Gardeners' Company to the scheme. The seed of this idea came from Tom Cotton's copies of 1930's encyclopedia entries on English towns that did not yet exist: Letchworth and Welwyn Garden Cities, "planned in advance and surrounded by a permanent belt of agricultural land." And they now knew which crops would thrive on the new level; so there was no need for experimentation. Francis liked the sound of "Wisbech Garden City."

Lastly, apprentice the children of prominent Dutch merchants to the corporation. The war on the continent was not going well for the United Provinces; it would allow fathers to get their sons and daughters safely out of the way of Spanish armies for a time. An example had come from a "Second World War" picture book; it had described English children being fostered abroad to escape war's ravages and hunger. The effort was to be circulated in the press and churches as "true Christian charity." The children would continue to learn their trades, and many would probably stay and make a life, thus tying their families' fortunes to the area. Let any man tell the Dutch children's accents from a fen man after five years, and Francis would pay him twenty pounds.

There was a lot still to think about. Francis quenched his pipe and reopened his account book. The bankers' meeting was next Thursday and the numbers seemed to total up quite well, but Vermuyden was coming over to be briefed tomorrow. Francis was unsure how that second meeting would go, on one hand his Director's name was still known in the future; "Vermuyden's Plans" had it's own place in the encyclopedia entry for the Great Fen. On the other, immediately thereafter the plan's shortcomings, losses to intentional flooding in a war, and how others had tried to resolve his flawed design might bruise a touchy ego.

Rob and the other groomsman knocked on the door of Englefield House, and then returned down to the bottom step. The white double doors opened, and two Irish lads waited; one in green and the other brown and blue corduroy jerkins, both decorated with blue flowers and green herbs.

"The brothers, I suppose," he speculated, not that he cared at this point.

"Will she come, lads? Tell us if your lady will come?" Rob's fellow groomsman asked the bridesmen barring the doorway.

The brothers turned inside the house, and returned escorting the bride. Her hair hung to her waist, her dress was all blue satin, pearls, flowers and mixed ribbons as she stood between their linked arms. "Aye, here she comes. We go to St. Marks to see her wed, do ye come?" they said in unison.

A large cheer from the villagers behind the groom's party responded favorably, and a few dirty suggestions volleyed over the back of Rob's head. A country wedding indeed!

The two groomsmen returned to their own party and watched as the bride's family and friends funneled through the front door and down the lane after the bride and her two brothers. Two bridesmaids tailed their group, as usual checking out the potential young bucks in both parties.

The bride's father nodded to Rob on the way past. They had negotiated the match between them in Dublin last month. After John Paulet's first wife, Jane had died suddenly; the pressure to marry him off again as quickly as possible had been, for a well-landed English nobleman, immense. The line must have more children; new alliances should be forged, and others quietly forgotten. The tight Roman Catholic community in England all had opinions on who John should marry, why, and for how much money.

Although not a Catholic, Robert had offered to take the pressure off. John had still not cared at that point, still missing his "bonnie Jane," and fretting after his only son.

Even though Grantville was said to change this world's story, Rob wasn't in the mood to push John's fate further. Milton's poem had been revived and revised for the funeral. John had been lost in his grief.

This girl was recorded in the histories as giving John healthy sons and daughters in the Other Place, so Rob had resigned himself to his task. If God pleased this to be, so would it be again. From John's biography, and knowing her given name "Honoura," it had not been hard; the history books had said she was Irish, obviously Roman Catholic, and titled. Her father owning Englefield clinched it, he was sure it was the right family

Rob had pressed his friend's case, and showed the information to the earl of Clanricarde, but the two had still tussled the terms between them this weekend past to settle for a dowry. Only then had the intended couple been allowed to meet for a short walk and conversation at Aldermaston on Monday.

The house, estate and rents of Englefield House would transfer to the groom's family. In return John and his new bride must follow the Irish tradition—thirty days in this house between wedding and returning to John's own home near Basingstoke. The estate workers had the traditional Irish wedding mead and the feast waiting in the main barn for after the ceremony.

Rob gathered the groom in his finery, and called the rest of the visiting party to order. His wife Mary held onto young Charles Paulet's hand on the half-mile walk to the church with the lad's nurse. Ellen Margaret Cotton, her first outing since her mourning period was completed, gathered the children to her, with the first signs of a tear in her eye. It was nice to see some color in her dress at last; yellow mourning clothes had not suited her at all the past year.

"Hmm, I'll ask Mary about seeing for Margaret also. All alone in a draughty house is not safe for a widow," Rob mused. In some part of his mind, he could have done without the additional paperwork of Connington on his plate. When he'd offered to stand witness to Tom's will in all the haste before traveling to Thuringia, he'd forgotten that there were no other Cotton men of age to be the prime executor.

"Ah, well." Robert smiled. He, too, could make best use of the next thirty days. At his request, John's estate steward had already been exchanging letters with his family at Hilgay in secret. Rob's recollection from years before, visiting between terms at Oxford, of John's main estate land and facilities had not been off course. Between them they had ventured that the happy couple's wedding present from the Weasenhams might help clear John's debts in three or four years, and set the family up for life.

In Grantville last year, Rob had been held in "isolation" for three weeks, whilst his cousin had suffered and died of his fever. The doctors had explained that the hot fever changes its mood periodically, and a few hundred years of changes had hit Tom's drink-weakened humours, or "immune system" hard. Tom had so wanted to meet the two ladies, and in his short happiness of seeing a new library, it had killed him.

While waiting to be allowed to leave Grantville, Rob had finally, with reluctance, turned to the books himself but naturally wanted to follow up on his family's specialty: the future trade market in the Germanies. He had bought or borrowed every book and pamphlet he could, including those from the Grange, the libraries, and the personal collections of the history "buffs" he had been introduced to.

The typical crops described from the encyclopedias in the twentieth century for Norfolk, and Lincolnshire areas had led to the making of some positive notes by Tom for the Gardeners'. Rob had laughed that the Dutch methods of vegetable farming were later called "The Norfolk method."

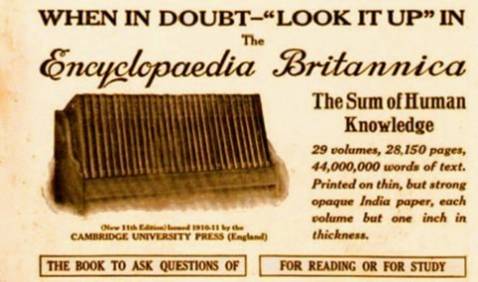

Back in England Rob's family and other landowners were interested in introducing all the crop varieties to the Level when the works completed. But in the meantime, they needed somewhere to try out some of the planting and refining methods described in the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica for one crop in particular.

In his last week Rob had delved into an enjoyable and entertaining read of some of the series of books following the character "Hornblower," some which mentioned the closing of European ports by the English during the Napoleonic War. It had had drawn parallels in Rob's mind to England's current trade gap. At the moment the most expensive international commodities went first to Amsterdam, Hamburg, Venice, or Istanbul. Without a strong English trade fleet London, Southampton, Lynn, Boston, and Bristol were at best secondary markets for some products, with all the appropriate mark-ups.

Excited, he had asked for other story and history books on the same period. Finally one had described, in some detail, a dinner in a future German province of "Prussia," in honor of Emperor Napoleon himself. It had shown an example of how some of the same Fen crops from the encyclopedia could replace the most expensive of this world's delicacies in the right market conditions. In Prussia and Silesia mills had made great profits in the early 1800s until that war ended. Rob thought there was a chance this could be done again; England now was just like the closed Continental ports during that other war. The venture would not work in Amsterdam or Hamburg, but with a Crown License, just might produce at home.

The groom's party entered the Norman church of St. Mark's, and the organ music changed to a more somber tone.

Back on the estate, a gilded box lay on the top table in the barn. The usual flowers and herbs garlanded all the walls, windows and table surfaces. Uniquely, two root crops lay next to the present. Mary still didn't quite believe he'd put a sample of red and white beetroots—Silesian winter cattle feed and sea kale—on a wedding table, but since there was no superstition to forbid him, she'd kept her mouth shut for once. Unknown to everyone but Robert, instructions on how to make sugar from these plants was locked in the box.

Rob took the small oilskin wrapped parcel from the shipmaster, and stepped carefully down the gangplank to the new wharf. God's teeth, the weather was awful! The parcel went under his arm as he strode back to town, the rain bouncing off his large brimmed hat, and overcoat.

"Filthy day, sir" said Mr. Bell, the customs man from the porch of his office at the entrance to the new timber dock. "Settle up tomorrow?"

Robert swept past, trying to keep the rain from his eyes. "Noon? We should get her unloaded by then " he called back.

Not waiting for a reply, and turned the corner onto Norwich Street, then through the puddles onto West Street, and on to his in-laws' house near the church.

Wisbech streets had changed somewhat in the past two years. The Bedford Levels Corporation had contracted with the town council to land supplies, fish, and additional laborers from the war-torn United Provinces, and to rent marshaling yards and build warehouses. Three new wharfs had been built recently, and the Weasenham family had taken a larger interest in the timber dock. His men were now to fulfill the contract for the new lock gates to be installed on the Nene and Ouse Rivers to hold back the high tides.

He passed a bustle of Dutch merchants in the churchyard, including Vermuyden and his young staff. Obviously they were heading to the Nene Ditch cutting through the town, and the engineer was extolling the new land opportunities of the next phase of drainage to potential investors. The decision of naming the first section of new town houses "Meadowlands" was great press.

"You had to admire the man," Robert thought. His plans had been savaged by information from Grantville, but with copies of other books from the libraries procured by Robert, he had taken to new engineering forms like "built-in redundancy" and "risk management" like a salmon going upriver to spawn. There might have been God's hand at work in the Germanies, war in the United Provinces, and a fickle king at home, but never try and keep a Zeelander from making money, or getting his hands on more land.

He winked at the very wet lad at the back of the Dutch contingent, Vermuyden's new apprentice, young van Rosevelt. Rob had served his time following his uncle in much the same way, lagging behind unnoticed in all weathers.

Master Mercer Robert Weasenham laughed at the cycle of life, and opened the side door. "Mary, I'm back!" he called, while brushing off his hat and hanging up his overcoat on the door peg. Shoes were dropped in the box by the door. No mud through the house, or there would be hell to pay.

"Captain Williams has your fabrics and packages from Hamburg. We'll get them offloaded tomorrow morning." Rob placed the package he carried on the kitchen table, and added, "And here's the naming present for John and Honoura."

Getting books and other printed material past the king's customs-men and censors was so much easier in Wisbech than the main port in Lynn, he thought with a wry smile.

Mary smiled back, and shooed him out of the kitchen fussing over flour and pastries.

Robert hurriedly took the parcel and went upstairs to his office. Better to get this done now, so the boy could take the post before the day was done. He sat down at his desk, and wrote a short note to John Paulet on fresh paper to go with the present.

To John and Honoura,

To you both, a short missive with another package from my agents in Hamburg. We would like you both to accept this storybook as a naming present in advance of the occasion of our godchild's birth.

Mary has a German copy of this book, and suggested we procure an original "Up-time" edition in English. Note the printers are the "Oxford University Press." Ironic, John, considering our labors cleaning presses and scraping parchment as punishments for failing the Rule at Exeter College.

In the Germanies and United Provinces, a fashion has taken for Ladies to read "Romantic Fiction." Publishers are spending a fortune translating hundreds of storybooks from the Grantville libraries, and they are in wide circulation. Most involve a formula following various trials and tribulations of a young Lady, and how she finds "Eternal Love with the Man of Her Dreams." Another American phrase you will have to get used to if the London publishers are ever allowed to print this kind of thing. Unfortunately for my purse, Mary has developed a taste for these and every three months receives parcels from a "Book Club" in Magdeburg. I have learned to pace my business trips to be away the week they arrive.

Mary tells me this book was seen in the might-have-been future as the most important and influential romantic fiction "novel" ever produced and to note it is written by a gentlewoman of quality, the daughter of a Church of England incumbent. No one may reproach Honoura to read it during her confinement.

The "Romance Appreciation Society" in Magdeburg has circulated a short biography of the author, which we also include. She was (would have been?) born in your county of Southamptonshire, or "Hampshire" as it will later be named, two hundred years from now. It may be interesting to inquire to see if the Austen family has as yet any association in society near Basingstoke.

Mary and I have selected this particular book as entertainment and for your interest as there is mention of your wife's family, although as a protagonist to the main character. If the sketch is true of the future, Honoura's family continues to be well connected at court, has prospered in London, and holds large estates in England (and I assume continue still in Ireland, although there is no mention of that).

However we must also include a "Glossary of Terms" as our English language has subtly changed in the next two hundred years. The researchers at the Grantville libraries were most helpful in collating the changed words, and alternate meanings. We must trouble you both to keep it at hand whilst reading.

A simple example of misunderstanding in the use of our mother tongue comes from my visit to Grantville two years ago. I was named a "Gentleman" in the first person singular during a conversation at dinner at a beer garden in town. I instantly lost my temper and of course tried to hit the man who called me thus, and needs must to be restrained by my colleagues.

A priest, a new visitor from Rome also dining that evening, stepped in and cleared up the confusion. He explained to me I was truly being described as a man of breeding and quality, and that the word had moved later in meaning back to the Old English form. To the surprised Americans at the table at my violent reaction, he added that to a Stuart Englishman they had unknowingly insinuated I was a court ponce or a pimp.

Obviously, the German or Dutch editions of these books do not have such confusions; the publishers take care to use local phrases to pass on the intended meaning during translation. A printer in Hamburg later explained it to me using another of these attractive American terms: "No point upsetting the target audience."

Gladly, Mary and I shall be happy to stand up for the child, and we thank you both for your kind offer. We hope and expect to be with you before the end of June in time for the birth.

However she believes we have found a way to decide the argument between you both on a name for the little one, and a suggestion.

Mary speculates using Honoura's family's' future Christian names, as shown in the book.

She suggests naming the child "Darcy" if a boy, or a girl "Catherine."

Yours,

Robert and Mary Weasenham

Robert folded the paper, unfolded one side of the parcel, and slid the note inside next to the exquisite up-time book and the glossary. Resealing the parcel, he wrote an address on a scrap piece of paper to give to the boy to send by messenger

To: The Marquis of Winchester Lord John Paulet,

and his Wife, Lady Honoura De Berg

Basing House

Southamptonshire

All the English characters are historical. The Englishmen attended or were around Exeter College, Oxford between 1610 and 1620. The Russell and Paulet families were heavily involved in developing the English woad experiments in their western estates in Cornwall and Dorset respectively.

The Weasenhams had been trading from Bishops Lynn (Renamed Kings Lynn in Tudor times) since the 1330s. The family were one the four strongest English trading families with links to the Hanseatic League, "The Hansa," until Queen Elizabeth expelled foreigners from England during her reign. By the time of this story, they have three hundred years of trade links with Hamburg and the other Baltic ports. There is still a fine example of Hansa building and a trade yard in Kings Lynn, behind a later Georgian fronting.

The Cottons were descended from a Weasenham branch that needed to marry a son off quickly to a rich heiress in the 1380s to avoid bankruptcy. They chose a girl from the Scots noble family "de Bruc," who included in her family tree a Scottish king, "Robert the Bruce" as we now call him. Tom's father, Sir Robert Cotton, meddled in politics frequently, and sidled up to the new King James when he came down from Scotland to take the English throne. Robert flashed his family tree, added "Bruce" as a middle name and ingratiated himself to the point that King James was later persuaded to call him "Cousin." Apart from a few short stays in the Tower of London, (a time-out zone for many a Privy Councilor) Sir Robert is famous for his Antiquarian Library, which became the one of the seeds of the British Library in 1750s, and inventing his own peculiar Caesarean classification system.

http://www.npg.org.uk/live/search/portrait.asp?search=ss&sText=cotton&LinkID=mp01052&rNo=0&role=sit

and a gorgeous one, recently found

http://www.trin.cam.ac.uk/sdk13/chartwww/miscimages/cotton.gif

Sir Thomas Cotton stayed out of the limelight and lived out his life at Connington Manor maintaining his father's library and adding to the family collection with contemporary architectural building plans, copies of navigation and colonial maps, and other ephemera, most of which was lost during a fire in the 1730s. There seems to have been an open deal in London where second copies of plans, log books, and anything else "useful" that they could get their hands on ended in the Library. "Fashionist" is a real word, and was first recorded in 1616 in London, then died from use within twenty years.

Sir Cornelius Vermuyden also "sucked up big time" to King James and King Charles, finally getting into land reclamation for wealthy Englishmen and the crown. Originally from Zeeland, he started as a tax collector in the United Provinces, became a naturalized Englishman in 1626, and persuaded fourteen other Dutch "adventurers" to fund the Bedford Level Corporation scheme. There is a disputed portrait of him in a private collection, but none available online.

Cornelius' new apprentice, Claes van Rosevelt, in this version of events has been diverted from going later to Nieuw Amsterdam, and buying the famous farm in what is now Midtown Manhattan. The Vermuyden and van Rosevelt families were from the same area in Zeeland, and were friends and business associates. As a Brit I felt had to have one small change in a piece of Americana.

The fourth earl of Bedford, Francis Russell, did not expect to inherit his title. Some cousins in the main line died in quick succession, and he was landed with diverse estates and the family title. Recorded as a details man in politics, he enjoyed the fussy work of Parliament in 1628/9, and in his projects to make money. He spent most of the 1630s working on the Great Fen project and as a property developer laying out the whole of Covent Garden in London from the Strand to what is now Russell and Bedford Squares.

http://www.npg.org.uk/live/search/portrait.asp?search=ss&sText=francis+russell&LinkID=mp68238&rNo=0&role=sit

The Fifth Marquis of Winchester, John Paulet was expected to inherit, but what he got were massive debts in 1628/9. His father died after twenty years of exorbitant dining, pleasures, and entertainments for guests at his home: Basing House, a larger and grander example of a Tudor mansion-style brick building than Hampton Court. John was no politician, and as his was a Roman Catholic family in trouble, decided to retire from court and quietly rebuild his family wealth. He did not appear again at court until 1639 when his second wife Honoura and the queen became friends. He is most famous for a holding action in the English Civil War, where Basing House was under siege by Parliamentarians for over two years. Eventually Cromwell himself had to come and finish the job: not surprisingly winning the day, and had the house flattened to the ground. John and family ended up in the Tower, but after the Restoration the Paulets retrieved all their estates. Lord John Paulet and his second wife Honoura are buried under the new, Victorian St. Marks' church in Englefield. The local post office, and nearby farm shop still sell honey.

http://www.npg.org.uk/live/search/portrait.asp?LinkID=mp53758&rNo=0&role=sit

The ruins of Basing House have been a tourist attraction on the road between London and Winchester for three hundred and fifty-odd years. Every year in late August there is a reenactment of the siege, with the "Sealed Knot" regiment on hand to show off Civil War military tactics.

http://www3.hants.gov.uk/hampshire-museums/basing-house

Gresham College, located in Bishopsgate, was founded to be the M.I.T. of London in 1597, paid for by the new Stock Exchange and the London Companies and Guilds. It's original charter was to provide public lectures, and apply the new knowledge becoming available from abroad to England in projects that made the city money. It has no students and awards no degrees. They were probably most successful in using mathematics to refine English shipbuilding methods, and improving magnetic compasses, giving rise to the new English trade fleet, and Royal Navy. After the Restoration Gresham College became the founding place of The Royal Society. The college still provides public lectures on science, history, culture, and finance.

http://www.gresham.ac.uk

Professor John Greaves, Chair of Geometry (Mathematics) 1631-32 at Gresham College specialized in Arabic Studies; he collected many science books from Turkey, and traveled to Egypt. His was the first modern description of the pyramids' dimensions and astronomical alignments in the mid 1640s. I was never quite sure where Dr Phil's fascination with pyramids came from, as information in the 1630s was almost impossible to find. Maybe he needs to talk to Professor Greaves, and arrange an expedition get the revised astral alignments needed ten years earlier to get his models to work?

The English silk makers trials in the first half of the seventeenth century with red mulberry from the Americas failed; those pesky worms still preferred the white variety to everything else. That's also why white mulberry trees are scattered over the east coast of America.

During the Continental Campaigns, Napoleon was presented with large sugar loaves made with processed sugar from sugar beet. After the Napoleonic Wars ended, Britain (and Portugal) flooded the European market with cane sugar from it's newly extended Caribbean island holdings, killing the price support mechanisms in place on the continent, with the result of holding back major sugar beet processing until the next Franco-Prussian war in the 1870s, and finally expanding worldwide after World War One. Prussia and Silesia continued to make sugar locally on a smaller scale, but at a profit.

Starting up a pilot sugar extraction and processing facility is going to be very possible, even with a seventeenth-century technology base. The 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica is very specific on each step, and the machinery needed for the method of sugar extraction from sugar beet (typically a cross between wild fodder beet and sea kale, but common beetroot will also do to start). There are only three logistical essentials—plentiful fresh water supplies, a ready supply of rock lime, and lots of wood or coal to heat the water and extract carbonic gasses from the lime. Old Basing village has the first two: the river Lodden passes fifty meters from Basing House, and the modern parish is studded with features like Lychpit Farm, and The Lime Pits Play Area (400 meters from the House). Lord John Paulet also owned Pamber Forest nearby, over five square miles in size. A Paulet family survey of their lands after the Restoration in the 1660s recorded the forest had been neglected for many years and had such poor quality mature timber, and significant underwood that was all only fit for burning. Manpower is not going to be a problem; unlike the continent at war, England is awash with farm laborers with hungry mouths to feed.

Why bother with homegrown sugar? In Tudor and Stuart times England sourced most of its fine quality sugar from the prisoner island of Madiera, the rest from Amsterdam. Interestingly, there was no sugar or molasses excise tax in England, this would not happen until over 120 years later. The price was set on the Venetian and Amsterdam markets, and tied to the inflation rate of gold. The English prices varied, but in general transportation costs using English merchant ships added around 30% to the Amsterdam wholesale price. (Punishing taxes were laden on cargoes from foreign vessels as a matter of state policy, in place since the 1380s to protect English merchants, and there was a fair amount of "flagging" of ships for much the same reasons we do it today). A general import tariff of around 20% was added when the cargo landed in port, as the product was not English, nor had it come from an English colony. If you had a town house in a port that traded in sugar, and could afford it, you bought it there. If you were in the country or an inland town or city, because of the weight and bulk of sugar loaves or lumps, the price could easily double again.

Thanks to British Sugar, for rules of thumb for the historic sugar price well before they were formed, and the Guildhall library, and the City Companies' archivists for helping me through the trade journals, and exchange rates.

Can English sugar make a profit? Well, that's another story for another day.